Table of Contents

- PREFACE

- 1. NEW ZEALAND

- 2. SUCCESSIVE GOVERNORS

- 3. EXECUTIVE COUNCIL, 1843-56

- 4. PARLIAMENTS

- 5. SUCCESSIVE MINISTRIES

- 6. PREMIERS,

WITH DATES OF THEIR ASSUMPTION OF AND RETIREMENT FROM OFFICE. WITH DATES OF THEIR ASSUMPTION OF AND RETIREMENT FROM OFFICE. - 7. SPEAKERS OF THE LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL,

WITH DATE OF THEIR APPOINTMENT AND DATE OF RETIREMENT OR DEATH. - 8. SPEAKERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES,

WITH DATES OF THEIR ELECTION AND DATES OF RETIREMENT OR DEATH. - 9. THE COLONIAL OFFICE

- 10. HONOURS HELD BY COLONISTS

- 11. FOREIGN CONSULS

- 12. AGENTS-GENERAL IN LONDON,

(With their Addresses) - 13. CROWN AGENTS FOR THE COLONIES

- 14. GOVERNOR OF NEW ZEALAND

- 15. EXECUTIVE COUNCIL, 1892.

His Excellency the GOVERNOR presides - 16. THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY

- LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL.

- ROLL OF MEMBERS

OF THE HONOURABLE THE

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL,

Stating the Provincial District in which Members reside, and the Date of Writ of Summons. - HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES.

- ROLL OF MEMBERS

OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES,

With the Name of the District for which they are elected, and the Date of Notification of Return of Writ.

- 17. ECCLESIASTICAL

- 18. OFFICIAL LIST.

[1st August, 1892.] - CIVIL ESTABLISHMENT AT SEAT OF GOVERNMENT

- COLONIAL SECRETARY'S DEPARTMENT

- COLONIAL TREASURER'S DEPARTMENT

- LAND- AND INCOME-TAX DEPARTMENT

- DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE

- POST OFFICE AND TELEGRAPH DEPARTMENT

- DEPARTMENT OF TRADE AND CUSTOMS AND MARINE

- MARINE

- STAMP DEPARTMENT

- LAND TRANSFER DEPARTMENT AND DEEDS REGISTRY

- EDUCATION DEPARTMENT

- DEPARTMENT OF LABOUR

- NATIVE DEPARTMENT

- MINES DEPARTMENT

- PUBLIC WORKS DEPARTMENT

- RAILWAY DEPARTMENT

- DEFENCE DEPARTMENT

- DEPARTMENT OF LANDS AND SURVEY

- AGRICULTURAL AND LIVE-STOCK DEPARTMENT

- GOVERNMENT LIFE INSURANCE DEPARTMENT

- PUBLIC TRUST OFFICE

- 19. ANNUAL PENSIONS

- 20. JUDICIAL

- 21. DEFENCES, MILITARY AND NAVAL

- MILITIA AND VOLUNTEER DISTRICTS.

- PERMANENT MILITIA.—ARTILLERY.

- PERMANENT MILITIA.—TORPEDO CORPS.

- VOLUNTEERS.—CAVALRY

- VOLUNTEERS.—MOUNTED RIFLES.

- VOLUNTEERS.—NAVAL ARTILLERY.

- VOLUNTEERS.—FIELD ARTILLERY.

- VOLUNTEERS.—ENGINEERS.

- VOLUNTEERS.—RIFLE CORPS.

- VOLUNTEERS.—CADET CORPS.

- ORDNANCE, ARMS, ETC.

- ENROLMENT, ETC.

- INSTRUCTORS.

- CAPITATION.

- ADMINISTRATION.

- 22. STATISTICAL INFORMATION

- 23. AGRICULTURE

- 24. THE FROZEN MEAT INDUSTRY

- 25. FOREST-TREES AND TIMBER INDUSTRY

- Order—CONIFERĈ

- Order—CUPULIFERĈ

- Order—MYRTACEĈ

- Order—MELIACEĈ

- Order—ONAGRARIEĈ

- Order—ARALIACEĈ

- Order—CORNEĈ

- Order—CCOMPOSITĈ

- Order—ERICEĈ

- Order—VVERBENAĈ

- Order—LAURINEĈ

- Order—MONIMIACEĈ

- Order—PROTEACEĈ

- Order—MAGNOLIACEĈ

- Order—VIOLARIEĈ

- Order—MALVACEĈ

- Order—TILIACEĈ

- Order—OLACINĈ

- Order—RHAMNEĈ

- Order—SAPINDACEĈ

- Order—CORIARIEĈ

- Order—LEGUMINOSĈ

- Order—SAXIFRAGEĈ

- Order—RUBIACEĈ

- Order—JASMINEĈ

- Order—SANTALACEĈE

- STRENGTH OF NEW ZEALAND TIMBERS

- NEW ZEALAND FUNGUS

- VALUE OF EXPORT TRADE

- THE TIMBER INDUSTRY

- 26. PHORMIUM TEN AX (NEW ZEALAND HEMP)

- 27. KAURI-GUM

- 28. LABOUR IN NEW ZEALAND

- 29. FISH AND FISHERIES

- 30. INTRODUCTION OF TROUT TO NEW ZEALAND

- 31. GOLD, COAL, AND OTHER MINERALS

- 32. HINTS TO PROSPECTORS FOE GOLD AND OTHER MINERALS

- 33. VARIETIES OF SOIL

- 34. BUILDING-STONES

- 35. BRICKS AND POTTERY

- 36. CLIMATE, TEMPERATURE, AND RAINFALL

- 37. MINERAL WATERS OF NEW ZEALAND

- THE THERMAL-SPRINGS DISTRICT AND THE GOVERNMENT SANATORIUM AT ROTORUA

- CLIMATE OF ROTORUA

- AREA OF THERMAL-SPRINGS DISTRICT

- PHYSICAL FEATURES

- VARIETIES OF MINERAL WATERS

- THE ROTORUA SANATORIUM

- THE HOSPITAL

- THE TARIFF

- THE PRIEST'S BATH

- THE PAVILION

- THE RACHEL BATH

- THE BLUE BATH

- CASES FOR TREATMENT

- CASES OF PARALYSIS

- A SUCCESSFUL CASE

- FURTHER CASES—PARAPLEGIA CURED

- RHEUMATISM AND SKIN-DISEASES

- CURES IN SEVERE RHEUMATISM

- GREAT SUCCESS IN CASES OF SKIN-DISEASE

- NEURALGIA

- CURATIVE EFFECTS OF MINERAL, WATERS

- VOLCANIC OUTBREAK AT ROTORUA

- ROTORUA AS A HEALTH RESORT

- ROUTE TO ROTORUA

- THE SANATORIUM WORKS AT ROTORUA

- MIDDLE ISLAND MINERAL SPRINGS

- 38. THE WEST COAST SOUNDS

- 39. RAILWAYS IN NEW ZEALAND: THEIR HISTORY AND PROGRESS

- 40. PORTS AND HARBOURS

- NORTH ISLAND

- AUCKLAND HARBOUR

- THAMES HARBOUR

- WAIHAU (COROMANDEL) HARBOUR

- MERCURY BAY

- TAURANGA HARBOUR

- TOLAGO BAY

- TURANGA (POVERTY BAY)

- NAPIER (OR AHURIRI) HARBOUR

- WELLINGTON (PORT NICHOLSON) HARBOUR

- WANGANUI RIVER

- PATEA HARBOUR

- NEW PLYMOUTH

- WAITARA RIVER

- KAWHIA HARBOUR

- MANUKAU HARBOUR

- KAIPARA HARBOUR

- MANGONUI HARBOUR

- WHANGAROA HARBOUR AND BAY

- BAY OF ISLANDS

- KORORAREKA BAY (PORT RUSSELL)

- WHANGAREI HARBOUR

- KAWAU BAY

- MIDDLE ISLAND.

- PORT LYTTELTON

- AKAROA HARBOUR

- PORT TIMARU (PATITI POINT).

- OAMARU HARBOUR,

- OTAGO HARBOUR

- BLUFF HARBOUR

- NEW RIVER HARBOUR, INVERCARGILL

- RIVERTON, JACOB'S RIVER

- THE WEST COAST SOUNDS

- HOKITIKA RIVER

- GREY RIVER

- BULLER RIVER (KAWATIRI), WESTPORT

- MOKIHINUI RIVER

- NELSON HAVEN

- PELORUS SOUND

- QUEEN CHARLOTTE SOUND

- PORT UNDERWOOD

- WAIRAU RIVER

- STEWART ISLAND.

- 41. RIVERS

- 42. GRAVING DOCKS AND PATENT SLIPS

- 43. LIGHTHOUSES

- 44. UNION STEAMSHIP COMPANY OF NEW ZEALAND (LIMITED)

- 45. THE NEW ZEALAND SHIPPING COMPANY (LIMITED)

- 46. SHAW SAVILL AND ALBION COMPANY (LIMITED)

- 47. TABLES OP DISTANCES, BY BAIL AND SEA

- 48. PUBLIC INSTRUCTION

- 49. NEW ZEALAND INSTITUTE

- 50. PUBLIC LIBRARIES AND MECHANICS' INSTITUTES

- 51. NEW ZEALAND GOVERNMENT LIFE INSURANCE DEPARTMENT

- 52. THE PUBLIC TRUST OFFICE OF NEW ZEALAND

- 53. PATENTS, DESIGNS, AND TRADE-MAKES

- 54. FIRE BRIGADES

- 55. FRIENDLY SOCIETIES

- 56. HOSPITALS

- 57. BENEVOLENT ASYLUMS AND CHARITABLE INSTITUTIONS

- 58. ORPHAN ASYLUMS

- 59. LUNATIC ASYLUMS

- 60. INDUSTRIAL SCHOOLS

- 61. COSTLEY TRAINING INSTITUTION, AUCKLAND

- 62. THE MAORIS: THEIR NUMBERS AND CONDITION AS AT PRESENT

- A. APPENDIX

- CROWN LANDS

- AREA OF THE COLONY (IN ACRES)

- LANDS AVAILABLE FOR SETTLEMENT

- CHARACTER OF THE LANDS SUITABLE FOR SETTLEMENT

- CROWN LANDS HELD ON PASTORAL LEASE

- LANDS HELD ON SETTLEMENT CONDITIONS

- NUMBER OF SELECTORS, 1891-92

- OPTIONAL SYSTEM OF LAND-TENURE

- ADMINISTRATION

- LAND DISTRICTS AND PRINCIPAL LAND OFFICES

- CLASSIFICATION OF LANDS

- TENURE

- MODE OF ACQUIRING CROWN LANDS

- CASH LANDS

- DEFERRED-PAYMENT LANDS

- PERPETUAL-LEASE LANDS

- PASTORAL RUNS

- SMALL, GRAZING-RUNS

- SMALL-FARM HOMESTEAD ASSOCIATIONS

- SUMMARY OF LANDS OPEN FOR SELECTION

- AUCKLAND

- HAWKE'S BAY

- TARANAKI

- WELLINGTON

- MARLBOROUGH

- NELSON

- CANTERBURY

- OTAGO

- SOUTHLAND

- WESTLAND

- CROWN LANDS GUIDE

- THE CUSTOMS TARIFF OF NEW ZEALAND

- POSTAL INFORMATION

- TELEGRAPHIC INFORMATION

- TELEPHONE EXCHANGES

- PRINCIPAL EVENTS

- B. ADDENDUM

- GENERAL INDEX

- C. STATISTICAL SUMMARY

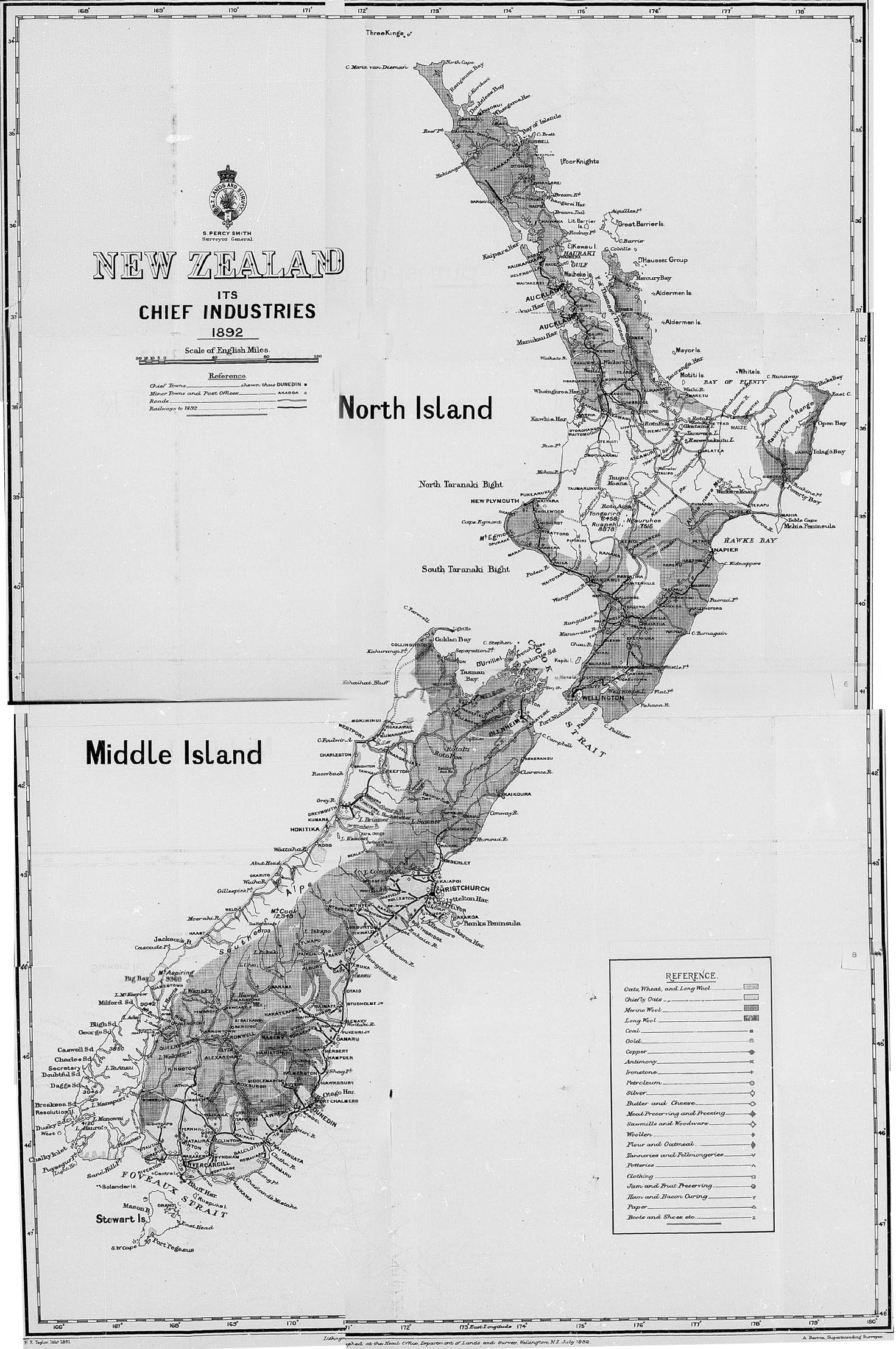

- D. MAPS

THE preparation of this Handbook was undertaken by direction of the Hon. John Ballance, Premier of the Colony, in the beginning of May last.

The requirement that the work should be ready some time during the present session of Parliament, necessitated very special effort being made; and at one time it seemed doubtful whether or not a work, at once comprehensive and sufficiently reliable to be published by authority, could be got ready in the space allowed.

Considerable difficulty is experienced in preparing a book which should give much detail and matter of reference to be of use to persons residing in the colony, and at the same time contain descriptive matter, not overloaded with particulars, for the purposes of persons abroad who desire to form a general idea of what is done in New Zealand, of the peculiar advantages of the colony for settlement and as a place of residence. It is hoped that the material of this Handbook will be found to combine what is wanted for reference purposes with sufficient illustrative matter to serve the requirements of persons at a distance.

To insure publication at so early a date as the 1st September, a few sacrifices have been found unavoidable. The results of the legislation of the present session could not be treated of, and full criminal and private school statistics for 1891 were not to hand. But, with these exceptions, the statistical portion of the work gives complete figures for last year.

Following on the official and statistical information will be found a series of articles on subjects of importance to the colony, such as the leading industries, means of transport, social institutions, &c. Some of these were furnished either wholly or in part from Government departments, and the freest acknowledgment of kindly and willing assistance is due to all.

Full use of the report of the late Registrar-General (Mr. W. R. E. Brown) has been made in preparing the “Statistical Information,” and preceding portion of the work.

The “Descriptions of Forest Trees,” “Strength of Timbers,” a portion of the articles on “Fish” and “Climate,” “Varieties of Soil,” and “Building Stones,” have been taken, by permission, from the works of Sir James Hector.

E. J. VON DADELSZEN.

Registrar-General's Office,

Wellington,

31st August, 1892.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.

| Special Articles on | Furnished by |

|---|---|

| Agriculture | M. Murphy, F.L.S.; J. A. Johnstone; J Sawers, through Department of Agriculture. |

| Kauri-gum | J. M. Dargaville, J.P. |

| Labour | E. Tregear, F.R.G.S., F.R. Hist S., Secretary, Labour Department. |

| Introduction of Trout | L. H. B. Wilson, Assistant Secretary, Marine Department. |

| Mining | H. A. Gordon, F.G.S., Mines Department. |

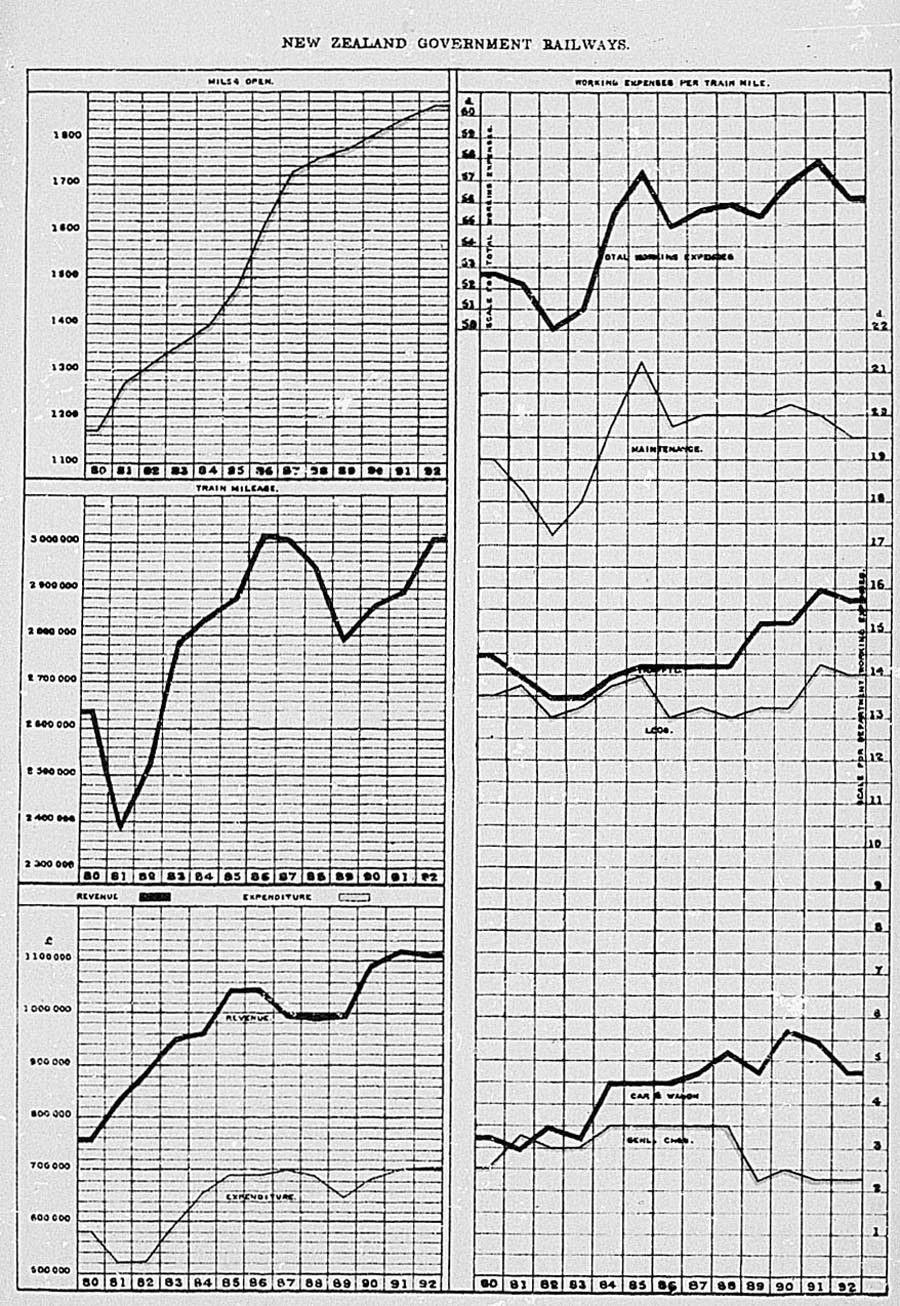

| Railways | E. G. Pilcher, Secretary, Railway Commissioners. |

| Union Steamship Company | The General Manager. |

| New Zealand Shipping Company | The General Manager. |

| Public Instruction | Rev. W. J. Habens, B.A., Secretary, Education Department. |

| Government Life Insurance | D. M. Luckie, F.S.S., Assistant Commissioner. |

| Public Trust Office | J. K. Warburton, Public Trustee. |

| Patents | C. J. A. Haselden, J.P., Registrar. |

| The Maoris | W. J. Morpeth, Native Department. |

| Map… … … | Surveyor-General. |

OFFICE ASSISTANCE.

| For Statistical and Critical Work | Officers of Registrar-General's Department. |

| For general assistance | Mr. Charles Janion. |

N.B. Every care has been taken to avoid errors, but if any be discovered it is requested that they may be reported. Suggestions will also receive consideration.

Table of Contents

THE Colony of New Zealand consists of three main islands, with several groups of smaller islands lying at some distance from the principal group. The former are known as the North, the Middle, and Stewart Islands. These three islands have a coast-line amounting to 4,330 miles in length—namely, North Island; 2,200 miles; South Island, 2,000 miles; and Stewart Island, 130 miles. The other islands now included within the colony are the Chatham Islands, Auckland Islands, Campbell Islands, Antipodes Islands, Bounty Islands, and the Kermadec Islands. A protectorate over the Cook Islands is exercised by the Imperial Government, the Governor of New Zealand acting as responsible adviser. The British Resident was appointed on the recommendation of the New Zealand Government.

New Zealand is a mountainous country in many parts, but has, nevertheless, large plains in both North and Middle Islands. In the North Island, which is highly volcanic, is situated the famous Thermal Springs District, of which a special account will be given. The Middle Island is remarkable for the lofty Alps with magnificent glaciers, and its sounds or fiords, the scenery being unrivalled.

New Zealand is firstly a pastoral, and secondly an agricultural country. Sown grasses are grown almost everywhere, the extent of land laid down being seven and a half millions of acres. The land is admirably adapted for receiving these grasses, which, after the bush has been burnt off, are mostly sown over without previous ploughing. In the Middle Island a large area is covered with native grasses, all used for grazing purposes. The large extent of good grazing-land has made the colony a great wool- and meat-producing country; and its agricultural capabilities are, speaking generally, very great. The abundance of water and quantity of valuable timber are also leading characteristics.

New Zealand is, besides, a mining country. Coal is found in immense quantities, chiefly on the west coast of the Middle Island. Gold, alluvial and in quartz, is found in both islands, the yield having been over forty-seven millions sterling in value to the present time. Full statistical information is given further on, compiled up to the latest dates.

The first authentic account of the discovery of New Zealand is that given by Abel Jansen Tasman, a Dutch navigator. He sailed from Batavia on the 14th August, 1642, in the yacht “Heemskirk,” accompanied by the “Zeehaen” (or “Sea-hen”) fly-boat. After having visited Mauritius and discovered Tasmania, named by him “Van Diemen's Land,” in honour of Anthony van Diemen, the Governor of the Dutch possessions in the East Indies, he sailed in an easterly direction, and on the 13th December of that year sighted the west coast of the Middle Island of New Zealand, described by him as “a high mountainous country, which is at present marked in the charts as New Zealand.”

It has been assumed as probable that the first European who visited New Zealand was Juan Fernandez, who, having started from one of the ports of the west coast of South America in 1576, after sailing for about a month in a south-westerly direction, reached a land described by him as fertile and pleasant, and inhabited by a race of white people, well made, and dressed in a species of woven cloth. People of brown complexions were often described as white by the Spaniards; and, although there is no direct evidence that the land so discovered was New Zealand, yet no other seems to answer his description. It appears, however, certain that the country was visited before the date of Tasman's arrival in 1642, as the land he came to was shown in the Dutch chart used by him, and was named thereon “Zeland Nova,” William Bleau, a Dutchman, who died in 1638, having published an atlas in which indistinctly a line of coast is shown with the name against it, “Zelandia Nova.”

Tasman, under the belief that the land he saw formed part of a great polar continent, and was part of that country (subsequently found to be an island) discovered some years before by Schouten and Le Maire, to which the name of Staaten Land had been given, gave the same name of Staaten Land to New Zealand. Within about three months after this date Schouten's “Staaten Land” was found to be merely an inconsiderable island. Upon this discovery being announced, the country which Tasman had called by the same name received instead that of “New Zealand”—an evident restoration of the name previously given—by which name it has ever since been known. Tasman sailed along the coast to a bay, where he anchored. To this he gave the name of Murderers (now Massacre) Day, on account of an unprovoked attack on a boat's crew by the Natives, and the massacre of four white men. Thence he sailed along the west coast of the North Island, and gave the name of Cape Maria van Diemen to the north-western extremity thereof. After sighting the islands of the Three Kings he finally departed, not having set foot on the country.

There is no record of any visit to New Zealand after Tasman's departure until that of Captain Cook, who, after leaving the Society Islands, sailed in a southerly direction in search of a southern continent then believed to exist. He sighted land on the 6th October, 1769, and on the 8th of that month cast anchor in Poverty Bay. After having circumnavigated the North Island and the Middle and Stewart Islands—the latter having been considered as part of the Middle Island—he sailed from Cape Farewell on the 31st March, 1770, for Australia. He again visited New Zealand in 1773, in 1774, and in 1777.

M. de Surville, a French officer in command of the vessel “Saint Jean Baptiste,” being on a voyage of discovery, sighted the northeast coast of New Zealand on the 12th December, 1769, and remained for a short time. Another visit was shortly after paid by a French officer, M. Marion, du Fresne, who arrived on the west coast of New Zealand on the 24th March, 1772, but was treacherously murdered by the Natives on the 12th June following.

In 1793 the “Dĉdalus,” under the command of Lieutenant Hanson, was sent by the Government of New South Wales to New Zealand, and two chiefs were taken thence to Norfolk Island. There was after this an occasional intercourse between the islands of New Zealand and the English settlements in New South Wales.

In 1814 the first missionaries arrived in New Zealand—Messrs. Hall and Kendall — who had been sent as forerunners to Mr. Marsden. After a short stay they returned to New South Wales, and on the 19th November of that year again embarked, in company with Mr. Marsden, who preached his first sermon in New Zealand on Christmas Day, 1814, and returned to Sydney on the 23rd March, 1815. It was not until 1821 that the work of evangelisation was put on a somewhat permanent basis; but the first station, established by Mr. Leigh, a Wesleyan missionary, and his wife, at the valley of the Kaeo, Whangaroa, was not taken possession of until the 10th June, 1823.

Prior to the discovery and colonisation of New Zealand by Europeans, the earliest navigators and explorers found a race of people already inhabiting both, islands. Papers written in 1874 by Sir William Fox, M.H.R., and Sir Donald McLean, then Native Minister, state that at what time the discovery was made by the Maoris, or from what place they came, are matters which are lost in the obscurity which envelops the history of a people, without letters. Nor is there anything on record respecting the origin of the Maori people themselves. Little more can now be gathered from their traditions than that they were immigrants, and that when they came there were probably no other inhabitants of the country. The tradition runs that, generations ago, a large migration took place from an island in the Pacific Ocean, to which the Maoris give the name of Hawaiiki, a chief having been driven from it whose canoe arrived upon the shore of the North Island. Returning to his home with a flattering description of the country he had discovered, this chief, it is said, set on foot a scheme of emigration, whereupon a large fleet of double canoes started for the new land. The names of most of the canoes are still remembered, and each tribe agrees in its account of the doings of the people of the principal “canoes” after their arrival in New Zealand; and from these traditional accounts the descent of the numerous tribes has been traced. Calculations, based on the genealogical staves kept by the tohungas, or priests, indicate that about twenty-seven generations have passed since the migration, which would give for its date about the beginning of the fourteenth century. The position of Hawaiiki is not known, but there are several islands of this or a somewhat similar name. Similarity of language indicates a Polynesian origin, which would prove that they advanced to New Zealand through various groups of the Pacific islands, in which they left remains of the same race, who to this day speak the same or nearly the same tongue. When Captain Cook first visited New Zealand he availed himself of the assistance of a native from Tahiti, whose language proved to be almost identical with that of the New Zealanders, and through the medium of whose interpretation a large amount of the early information respecting the country and its inhabitants was obtained, which could not have been had without it.

A special article will be found further on dealing with the subject of the numbers and present condition of the Maoris.

The first attempt at colonisation was made in 1825 by a company formed in London. An expedition was sent out under the command of Captain Herd, who bought two islands in the Hauraki Gulf and a strip of land at Hokianga. The attempt, however, was a failure, owing to the savage character of the inhabitants. In consequence of frequent visits of numerous whaling vessels to the Bay of Islands, a settlement grew up at Kororareka—now called Russell—and in 1833 Mr. Busby was appointed British Resident there. A number of Europeans—generally men of low character—gradually settled in different parts of the country, and married Native women.

In 1838 a colonisation company, known as the New Zealand Company, was formed to establish settlement on systematic principles. A preliminary expedition, under the command of Colonel William Wakefield, was despatched from England on the 12th May, 1839, and arrived in New Zealand in the following August. Having purchased land from the Natives, Colonel Wakefield selected the shore of Port Nicholson, in Cook Strait, as the site of the first settlement. On the 22nd January, 1840, the first body of immigrants arrived, and founded the town of Wellington. About the same time—namely, on the 29th January, 1840—Captain Hobson, R.N., arrived at the Bay of Islands, empowered, with the consent of the Natives, to proclaim the sovereignty of the Queen over the islands of New Zealand, and to assume the government thereof. A treaty called “The Treaty of Waitangi,” to which in less than six months five hundred and twelve names were affixed, was entered into, by which all rights and powers of sovereignty were ceded to the Queen, all territorial rights being secured to the chiefs and their tribes. New Zealand was then constituted a dependency of the Colony of New South Wales; but on the 3rd May, 1841, it was proclaimed a separate colony. The seat of Government had been previously established at Auckland, round which a settlement was formed.

The New Zealand Company having decided to form another settlement, to which the name of “Nelson” was to be given, despatched a preliminary expedition from England in April, 1841, for the purpose of selecting a site, which resulted in the establishment of the settlement at the head of Blind Bay. About the same time a settlement was commenced at New Plymouth, by the arrival, on the 31st March, 1841, of a body of immigrants despatched by the New Plymouth Company, a colonisation company that had been formed in England, and had purchased 50,000 acres of land from the New Zealand Company.

The next important event in the progress of colonisation was the arrival at Port Chalmers, in March, 1848, of two ships containing immigrants, despatched by the Otago Association for the foundation of a settlement in that part of the colony by persons who belonged to or were in sympathy with the Free Church of Scotland.

In 1849 the “Canterbury Association for founding a Settlement in New Zealand” was incorporated. On the 16th December, 1850, the first emigrant ship despatched by the association arrived at Port Cooper, and the settlement of the adjoining country was commenced in a systematic manner, the intention having been to establish a settlement complete in itself, and composed entirely of members of the then United Church of England and Ireland.

The Proclamation of Captain Hobson on the 30th January, 1840, gave as the boundaries of the colony the following degrees of latitude and longitude: On the north, 34° 30′ S. lat.; on the south, 47° 10′ S. lat.; on the east, 179°.0′ E. long.; on the west, 166° 5′ E. long. These limits excluded small portions of the extreme north of the North Island and of the extreme south of Stewart Island.

In April, 1842, by Royal Letters Patent, and again by the Imperial Act 26 and 27 Vict., c. 23, 1863, the boundaries of the colony were altered so as to extend from 33° to 53° of south latitude and from 162° of east longitude to 173° of west longitude. By Proclamation bearing date the 21st July, 1887, the Kermadec Islands, lying between the 29th and 32nd degrees of south latitude and the 177th and 180th degrees of west longitude, were declared to be annexed to and to become part of the Colony of New Zealand.

The following now constitute the Colony of New Zealand:—

The island commonly known as the North Island, with its adjacent islets, having an aggregate area of 44,468 square miles, or 28,459,580 acres.

The island known as the Middle Island, with adjacent islets, having an aggregate area of 58,525 square miles, or 37,456,080 acres.

The South or Stewart Island, and adjacent islands, having an area of 665 square miles, or 425,390 acres.

The Chatham Islands, situate 536 miles eastward of Lyttelton, in the Middle Island, with an area of 375 square miles, or 239,920 acres.

The Auckland Islands, about 200 miles south of Stewart Island, extending about 30 miles from north to south, and nearly 15 from east to west, the area being 210,650 acres.

The Campbell Islands, in latitude 52° 33′ south, and longitude 169° 8. west, about 30 miles in circumference, with an area of 45,440 acres.

The Antipodes Islands, about 458 miles in a south-easterly direction from Port Chalmers, in the Middle Island. These are detached rocky islands, and extend over a distance of between four and five miles from north to south. Area, 12,960 acres.

The Bounty Islands, a small group of islets, thirteen in number, lying north of the Antipodes Islands, and about 415 miles in nearly an east-south-easterly direction from Port Chalmers. Area, 3,300 acres.

The Kermadec Islands, a group of which the largest is called Sunday or Raoul Island, lie about 614 miles to the north-east of Russell, in the Bay of Islands. Sunday Island is about 20 miles in circuit. The next in size is Macaulay Island, about three miles in circumference. Area of the group, 8,144 acres.

The total area of the colony is thus about 104,471 square miles, of which the aggregate area of the outlying groups of islands that are practically useless for settlement amounts to about 438 square miles.

A protectorate is exercised by the Imperial Government over the Cook Islands (or Hervey group) by Proclamation dated the 27th October, 1888. The British Resident* is appointed on the recommendation of the New Zealand Government. He acts for the colony as Government Agent in all matters of trade.

* Frederick J. Moss, Esq., late M.H.R., is now British Resident. His salary is paid by this colony.

The areas of the various Australian Colonies, as given by different authorities, differ considerably. Mr. Hayter, in his “Victorian Year-book,” gives the total area of the Australian Continent at 2,944,628 square miles, according to a computation made by the late Surveyor-General of Victoria, Mr. J. A. Skene, from a map of Continental Australia compiled and engraved under his direction; but in the case of each colony, except Victoria, the area computed by Mr. Skene differs from that given in the official records of that colony, the difference in the case of Western Australia amounting to over 84,000 square miles. The following areas are, therefore, taken from the official records of each colony:—

| Square Miles | |

|---|---|

| Queensland | 668,497 |

| New South Wales | 310,700 |

| Victoria | 87,884 |

| South Australia | 903,600 |

| Western Australia | 1,060,000 |

| Total Continent of Australia | 3,030,771 |

| Tasmania | 26,375 |

| New Zealand (including the Chatham and other islands) | 104,471 |

| Total Australasia | 3,161,617 |

The size of these colonies may be better realised by the comparison of their areas with those of European countries. The areas of the following countries—Austria-Hungary, Germany, France, Belgium, Holland, Denmark, Sweden and Norway, Portugal, Spain, Italy (including Sardinia and Sicily), Switzerland, Greece, Roumania, Bulgaria, Servia, Eastern Roumelia, and Turkey in Europe—amounting on the whole to less than 1,600,000 square miles, are little more than half the area of the Australian Continent. If the area of Russia in Europe be added to those of the other countries the total area would be about one-seventh larger than the Australian Continent, and about one-twelfth larger than that of the Australasian Colonies, including New Zealand. The area of the Colony of New Zealand is little more than one-seventh less than the area of Great Britain and Ireland, that of the Middle Island of New Zealand being a little larger than the combined areas of England and Wales.

| United Kingdom. | Area in Square Miles. |

| England and Wales | 58,311 |

| Scotland | 30,463 |

| Ireland | 32,531 |

| Total | 121,305 |

| New Zealand. | Area in Square Miles. |

| North Island | 44,468 |

| Middle Island | 58,525 |

| Stewart Island | 665 |

| Chatham Islands | 375 |

| Other islands | 438 |

| Total | 104,471 |

The North Island extends over a little more than seven degrees of latitude—a distance in a direct line from north to south of 430 geographical or 498 statute miles; but, as the northern portion of the colony, which extends over more than three degrees of latitude, takes a north-westerly direction, the distance in a straight line from the North Cape to Cape Palliser, the extreme northerly and southerly points of the island, is about 515 statute miles.

This island is, as a whole, hilly, and, in parts, mountainous in character, but there are large areas of plain or comparatively level country available, either now or in the future, when clear of forest or other indigenous vegetation, &c., for agricultural purposes. Of these, the principal are the plains in Hawke's Bay on the East Coast, the Wairarapa Plain in the Wellington District, and a strip of country along the West Coast extending from a point about thirty miles from the City of Wellington to a little north of New Plymouth, which is about 250 miles distant from Wellington. The largest plain in the North Island, Kaingaroa, extends from the shore of Lake Taupo in a north-north-easterly direction to the sea-coast in the Bay of Plenty; but a large portion is covered with pumice-sand, and is unsuitable for beneficial occupation. There are several smaller plains and numerous valleys suitable for agriculture. The level or undulating country in this island suitable for or capable of being made fit for agriculture has been estimated roughly at 13,000,000 acres. This includes lands now covered with standing forest, and swamps that are capable of drainage; also considerable areas of clay-marl and pumice-covered land. The clay-marl in its natural state is cold and uninviting to the agriculturist, but under proper drainage and cultivation it can be brought to a high state of productiveness. This kind of land is generally neglected at the present time, as settlers prefer soils more rapidly remunerative and less costly to work. The larger portion of this island was originally covered with forest. Although the area of forest-covered land is still very great, yet year by year the amount is being reduced, chiefly to meet the requirements of settlement, the trees being cut down and burnt, and grass-seed being then sown on the ashes to create pasture. Hilly as the country is, yet from the nature of the climate it is especially suited for the growth of English grasses, and wherever there is any soil, however steep the land may be, grasses will flourish. Very little of the land is consequently incapable of being made to supply food for cattle and sheep when treated as above or otherwise laid down in grass. The area of land in the North Island deemed purely pastoral or capable of being made so, being too steep for agricultural purposes, is estimated at 14,200,000 acres. In the centre of the island is a lake, about twenty miles across either way from the extreme points, called Taupo. A large area adjacent to the lake is at present worthless pumice-country. The Waikato River, the largest in the North Island, rising to the south of the lake, flows through it and out of its north-eastern point, and trends thence in a north-westerly direction until it flows into the ocean a little distance south of the Manukau Harbour. This river is navigable for small steamers for about a hundred miles from its mouth. The Maori King-country, occupied by Natives who for several years isolated themselves from the Europeans, lies to the west of Lake Taupo, and is bounded on the west by the sea. The River Thames, or Waihou, having its sources north of Lake Taupo, flows northward into the Firth of Thames. It is navigable only for small steamers about fifty miles. The other navigable rivers in this island are the Wanganui and Manawatu, which flow in a south-westerly direction into Cook Strait.

The mountains in the North Island are estimated to occupy about one-tenth of the surface, and do not exceed 4,000ft. in height, with the exception of a few volcanic mountains that are more lofty. Of these, the three following are the most important:—

The Tongariro Mountain, situated to the southward of Lake Taupo. It consists of a group of distinct volcanic cones, the lava-streams from which have so overlapped in their descent as to form one compact mountain-mass at the base. The highest of these cones is that of Ngauruhoe, which attains an elevation of 7,515ft. The craters of Ngauruhoe, the Red Crater (6,140ft.), and Te Mari (4,990ft.) are the three vents from which the latest discharges of lava have taken place, the most recent having occurred in 1868. These craters are still active, steam and vapour issuing from them with, at times, considerable force and noise, the vapours being charged with pungent gases and acids, making it dangerous to approach too near the crater-lips.

Ruapehu. This mountain lies to the south of Tongariro. It is an extinct volcanic cone, and reaches the height of 9,100ft., being in part considerably above the line of the limit of perpetual snow. The most remarkable feature of this mountain is the crater-lake on its summit. This lake is situated at the bottom of a funnel-shaped crater, its steep sides being mantled with ice and snow. The water occupies a circular basin about 500ft. in diameter, and is about 300ft. below the enclosing peaks, and quite inaccessible except by ropes. It is much disturbed by eddies, from which steam or vapour is given off. This lake, and the three craters previously mentioned on Tongariro, are all in one straight line, which, if produced, would pass through the boiling springs at Tokaanu on the southern margin of Lake Taupo, and through other hot springs on the north of the lake in the direction of White Island, an active volcano in the Bay of Plenty, situated about twenty-seven miles from the mainland.

Mount Egmont. This is also an extinct volcanic cone, rising to a height of 8,300ft. The upper part is always covered with snow. This mountain is situated close to New Plymouth, and is surrounded by one of the most fertile districts in New Zealand. Rising from the plains in its solitary grandeur, it is an object of extreme beauty and ceaseless admiration.

It is estimated that the area of mountain-tops and barren country at too high an altitude for sheep, and therefore worthless for pastoral purposes, amounts, in the North Island, to 300,000 acres.

The most remarkable feature of the North Island is the numerous hot springs, which occur in hundreds from Tongariro, south of Lake Taupo, to Ohaeawai, situated at almost the extreme north of the colony—a distance of 300 miles. Clouds of sulphurous steam are seen rising at all sorts of places over this extensive area, but the principal seat of hydrothermal action appears to be in the neighbourhood of Lake Rotorua. The district is generally known as the Hot- or Thermal-Springs District.

This district is situated about forty miles in a north-north-east direction from Lake Taupo. By the destruction of the famed Pink and White Terraces and of Lake Rotomahana on the occasion of the eruption of Mount Tarawera on the 10th June, 1886, the district has been deprived of attractions unique in character and of unrivalled beauty; but the natural features of the country—the lakes, geysers, and hot springs (the number of which is very great), some of which possess remarkable curative properties for certain complaints—still afford considerable attraction for tourists and invalids. Recently the world-wide importance of conserving this region as a sanatorium for all time has been recognised by the Government, and it is now dedicated by Act of Parliament to that purpose. A very interesting account of the “Thermal Springs of the North Island” will be found further on.

Notwithstanding the length of coast-line, good harbours in the North Island are not numerous. These on the west coast north of New Plymouth are bar-harbours, not suitable for large vessels. The principal harbours are the Waitemata Harbour, on which Auckland is situated—this is rather a deep estuary than a harbour; several excellent harbours in the northern peninsula; and Port Nicholson, on the borders of which Wellington is situated. This is a land-locked harbour, about six miles across, having a comparatively narrow but deep entrance from the ocean. The water is deep nearly throughout.

Cook Strait separates the North and Middle Islands. It is about sixteen miles across at its narrowest part, but in the widest about ninety. The strait is invaluable for the purpose of traffic between different parts of the colony, and is constantly traversed by vessels of the magnificent line of coastal steamers that trade in New Zealand waters.

The extreme length of the Middle Island, from Point Jackson, in Cook Strait, to Puysegur Point, at the extreme south-west, is about 525 statute miles; the greatest distance across at any point is in Otago (the southern) District, being about 180 miles.

The Middle Island is intersected along almost its entire length by a mountainous range known as the Southern Alps. Some of the summits reach a height of from 10,000ft. to 12,000ft., Mount Cook, the highest peak, attaining an altitude of 12,349ft.

In the south, in the vicinity of the sounds and Lake Te Anau, there is a large number of magnificent peaks, which, though not of great height, are, owing to their southerly position, nearly all crowned with perpetual ice and snow. Further north the mountains increase in height—Mount Earnslaw, at Lake Wakatipu; and Mount Aspiring, which has aptly been termed the New Zealand Matterhorn, nearly 10,000ft. in height, at Lake Wanaka. North-ward beyond this a fine chain of peaks runs as the backbone of the Middle Island to where Mount Cook, or Aorangi, towers majestic in the midst of the grandest scenes of the Southern Alps.

The scenery of the Southern Alps of New Zealand in many instances excels in beauty and grandeur that of the Alps of Switzerland, while in the Southern Alps there is also greater variety. In New Zealand no one has actually succeeded in making a complete ascent of any of the highest mountains. Many of the peaks and most of the glaciers are as yet unnamed; and there is, in parts of the Middle Island, still a fine field for exploration and discovery—geographical, geological, and botanical. The wonders of the Southern Alps are only beginning to be known; but the more they are known the more they are appreciated. The snow-line in New Zealand being so much lower than in Switzerland, the scenery, though the mountains are not quite so, high, is of surpassing grandeur.

There are extensive glaciers on both sides of the range, those on the western side being of exceptional beauty, as, from the greater abruptness of the mountain-slopes on that side, they descend to within about 700ft. of the sea-level, and into the midst of the evergreen New Zealand forest vegetation. The largest glaciers on each side of the range are easily accessible.

The following gives the sizes of some of the glaciers on the eastern slope:—

| Name. | Area of Glacier. | Length of Glacier. | Greatest Width. | Average Width. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acres. | Miles | ch. | Miles | ch. | Miles | ch. | |

| Tasman | 13,664 | 18 | 0 | 1 | 14 | 1 | 15 |

| Murchison | 5,800 | 10 | 70 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 66 |

| Godley | 5,312 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 55 | 1 | 3 |

| Mueller | 3,200 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 61 | 0 | 50 |

| Hooker | 2,416 | 7 | 25 | 0 | 54 | 0 | 41 |

The Alletsch Glacier, in Switzerland, according to Ball, in the “Alpine Guide,” has an average width of one mile. It is in length and width inferior to the Tasman Glacier.

Numerous sounds or fiords penetrate the mountains abutting on the south-western coast, from the sea. They are long, narrow, deep (the depth of water at the upper part of Milford Sound is 1,270ft., although at the entrance only 130ft.), environed by giant mountains clothed with foliage to the snow-line; their steep sides often apparently within the steamer's length of the deck as she ploughs through their calm solitudes, with waterfalls, glaciers, and snow-fields at every turn. Some of the mountains rise almost precipitously from the water's edge to 5,000ft. and 10,000ft. above the sea. The great Sutherland Waterfall, 1,904ft. high, is near one of these sounds.

The general surface of the northern portion of the Middle Island, comprising the Provincial Districts of Nelson and Marlborough, is mountainous, but the greater part is suitable for grazing purposes. There are, some fine valleys and small plains suitable for agriculture, of which the Wairau Valley or Plain is the largest. Deep sounds, extending for many miles, break the coast-line abutting on Cook Strait. The City of Nelson is situated at the head of Blind Bay, which has a depth inwards from Cook Strait of about forty statute miles.

The Provincial District of Canterbury lies to the south of the Marlborough District, and on the eastern side of the island. Towards the north the land is undulating; then there is a stretch of almost perfectly level country extending in a south-westerly-direction for 160 miles, after which, on the south, the country is undulating as far as the borders of the Otago District. On the east a block of hill-country rises abruptly from the plain and extends for some miles seaward. This is Banks Peninsula, containing several good harbours, the principal being Port Cooper, on the north, on which is situated Lyttelton, the chief port of the district: the harbour of Akaroa, considered one of the finest in the colony, is on the southern coast of this peninsula.

The southern district of Otago is, on the whole, mountainous, but has many fine plains and valleys suitable for agricultural purposes. The mountains, except towards the west coast, are generally destitute of timber, and are suitable for grazing sheep. There are gold-fields of considerable extent in the interior of this district. The interior, lakes are very important features in Otago. Lake Wakatipu extends over fifty-four miles in length, but is not more than four miles at its greatest width. It is 1,070ft. above sea-level, and has a depth varying from 1,170ft. to 1,296ft. It covers an area of 114 square miles. Te Anau Lake, which covers an area of 132 square miles, is larger than Lake Wakatipu. These lakes are bounded on the west by broken, mountainous, and chiefly wooded country, extending to the ocean.

The chief harbours in the Otago District are those of Port Chalmers, at the head of which Dunedin is situated, and the Bluff Harbour, at the extreme south.

The District of Westland extends along the west coast of the Middle Island, abreast of the District of Canterbury. This district is more or less auriferous throughout. The western slopes of the central range of mountains are clothed with forest-trees to the snowline; but on the eastern slopes timber is scarce, natural grasses covering the ground.

The rivers in the Middle Island are for the most part mountain-torrents, fed by glaciers in the principal mountain-ranges. When the snow melts they become of considerable size, and their beds, when not confined by rocky walls, extend over considerable areas, chiefly covered by enormous deposits of shingle. The largest river in the island and in the colony is the Clutha. It is 154 miles in length, but is only navigable for boats or small river-steamers for about thirty miles. The rivers Buller, Grey, and Hokitika, on the West Coast, are navigable for a short distance from their mouths. They constitute the only ports in the Westland District. In their unimproved state they only admitted, owing to the bars at their mouths, vessels of small draught; but, in consequence of the importance of the Grey and Buller Rivers as the only ports available for the coal-export trade, the largest and most important coalfields being in their neighbourhood, large harbour-works have been undertaken, resulting in a deepening of the beds of these rivers, and giving a depth of from 18ft. to 24ft. of water on the bars.

The area of level or undulating land in the Middle Island that may be available for agriculture is estimated at about 15,000,000 acres. About 13,000,000 are suitable for pastoral purposes only, or may become so when cleared of forest and sown with grass-seed. The area of barren land and mountain-tops is estimated at about 8,000,000 acres.

Foveaux Strait separates the Middle from Stewart Island. This last island has an area of only 425,390 acres. It is mountainous in character, and chiefly covered with forest.

The outlying group of the Chatham Islands, 480 statute miles east-south-east from Wellington, and 536 miles eastward of Lyttelton, consists of two principal islands and several unimportant islets. The largest island contains about 222,490 acres, of which a largo and irregularly-shaped lake or lagoon absorbs 45,960 acres. About one quarter of the surface of the land is covered with forest, the rest with fern or grass. The hills nowhere rise to a great height. Pitt Island is the next in size; the area is 15,330 acres. The greater portion of both islands is occupied as sheep-runs.

The only island in any way suitable for settlement in the Kermadec group is Sunday Island, containing 7,800 acres. The highest point rises to an elevation of 1,720ft. The surface of the land is chiefly covered with wood and scrub. The other islands are mere rocks.

The largest of the Auckland Islands, about twenty-seven miles long by about fifteen miles broad, is very mountainous, the highest part being 2,000ft. above the sea. The west coast is bold and precipitous, but the east coast has several inlets. There is a good harbour both at the north and south ends. The wood on the island is, owing to the strong prevailing wind, scrubby in character. The New Zealand Government maintains at this island a dépôt of provisions and clothing for the use of shipwrecked mariners. These have already been found of inestimable value by an unfortunate shipwrecked crew condemned to some months' residence on the island.

Neither this nor the rest of the outlying islands of the group are suitable for settlement.

British sovereignty was proclaimed over New Zealand in January, 1840, and the country became a dependency of New South Wales until the 3rd May, 1841, when it was made a separate colony. The seat of Government was at Auckland, and the Executive comprised, with the Governor, three gentlemen, holding offices as Colonial Secretary, Attorney-General, and Colonial Treasurer.

In August, 1841; May, 1842; and January, 1844, three new members were nominated by Her Majesty as ex officio members of the Executive Council. They were not members of the General Assembly, opened for the first time on the 27th May, 1854, although they remained in office until the establishment of Responsible Government on the 7th May, 1856. Between the 14th June and the 2nd September, 1854, the Executive Council was variously constituted with three or four members of the House of Representatives and two Legislative Councillors, without portfolios.

The government of the colony was at first vested in the Governor, who was responsible only to the Imperial Government; but in 1852 an Act was passed by the Imperial Legislature which granted representative institutions to the colony. Under it the constitution of a General Assembly for the whole colony was provided for, consisting of a Legislative Council, the members of which were to be nominated by the Governor, and an elective House of Representatives. The first session of the General Assembly was opened on the 27th May, 1854, but the members of the Executive were not responsible to Parliament. The first Ministers under a system of Responsible Government were appointed on the 18th April, 1856. By the Act of 1852 the colony was divided into six provinces, each to be presided over by an elective Superintendent, and to have an elective Provincial Council, empowered to legislate, except on certain specified subjects. The franchise practically amounted to household suffrage. In each case the election was for four years; but a dissolution of the Provincial Council by the Governor could take place at any time, necessitating a fresh election both of the Council and of the Superintendent. The Superintendent was chosen by the electors of the whole province; the members of the Provincial Council by those of the electoral districts. The Provincial Governments remained as integral parts of the Constitution of the colony until the 1st November, 1876, when they were abolished by an Act of the General Assembly, that body having been vested with the power of altering the Constitution Act. On the same day an Act of the General Assembly which subdivided the colony (exclusive of the areas included within municipalities) into counties, and established a system of local county government, came into operation.

The Governor is appointed by the Queen. His salary is £5,000 a year, and is provided by the colony.

The present members of the Legislative Council hold their seats under writs of summons from the Governor, the appointments being for life unless vacated by resignation or extended absence. Two of the members of the Council are aboriginal native chiefs. In future the appointments are tenable for seven years only; but Councillors may be reappointed.

The members of the House of Representatives are elected for three years from the time of each general election; but at any time the dissolution of Parliament by the Governor necessitates such general election. Four of the members are representatives of Native constituencies, three members for the Maori districts being aboriginal natives and one a half-caste. An Act was passed in 1887 which provided that, on the termination of the then General Assembly, the number of members to be thereafter elected to the House of Representatives should be seventy-four in all, of whom four were to be elected under the provisions of the Maori Representation Acts, as representatives of Maori electors only. For the purposes of European representation the colony is divided into sixty-two electoral districts, four of which—the Cities of Auckland, Wellington, Christchurch, and Dunedin—return each three members, and all the other electorates one each. Members of the House of Representatives are chosen in every electoral district appointed for that purpose by the votes of the inhabitants.

In 1889 an amendment of the Representation Act was passed, which contained a provision prohibiting any elector giving his vote in respect of more than one electorate at any election. This provision greatly increased the effective power of those voters who were registered for one electoral district only, and resulted in a considerable addition to the number of so-called labour members in the House of Representatives. Every man registered as an elector, and not coming within the meaning of section 2 of “The Public-Offenders Disqualification Act, 1867,” but no other man, is qualified to be elected a member of the House of Representatives for any electoral district. The franchise for European representation is that every adult male, if resident one year in the colony and six months in one electoral district, can be registered as an elector. Freehold property of the value of £25 held for six months preceding the day of registration also entitles a man to register, if not already registered under the residential qualification. Maoris possessing a £25 free-hold under Crown title, or being on any ratepayers' roll, can also register. For Maori representation every adult Maori resident in any Maori electoral district (of which there are four only in the colony) can vole. Registration is not required in Native districts. The proportion of representation to population at the last general election for the House of Representatives, in December, 1890, was one European member to every 8,952 inhabitants, and one Maori member to every 10,413 Natives.

Up to the year 1865 the seat of Government of New Zealand was at Auckland. Several attempts were made by members of Parliament, by motions in the Legislative Council and House of Representatives, to have it removed to some more central place; but it was not until November, 1863, that Mr. Domett (then late Premier) was successful in carrying resolutions in the House of Representatives that steps should be taken for appointing some place in Cook Strait as the permanent seat of Government in the colony. The resolutions adopted were: “(1.) That it has become necessary that the seat of Government in the colony should be transferred to some suitable locality in Cook Strait. (2.) That, in order to promote the accomplishment of this object, it is desirable that the selection of the particular site in Cook Strait should be left to the arbitrament of an impartial tribunal. (3.) That, with this view, a Bill should be introduced to give effect to the above resolutions.” On the 25th November an address was presented to the Governor, Sir George Grey, K.C.B., by the Commons of New Zealand, requesting that the Governors of the Colonies of New South Wales, Victoria, and Tasmania might be asked to each appoint one Commissioner for the purpose of determining the best site in Cook Strait. Accordingly, the Hon, Joseph Docker, M.L.C., New South Wales; the Hon. Sir Francis Murphy, Speaker of the Legislative Council, Victoria; and E. C. Gunn, Esq., Tasmania, were appointed Commissioners.

These gentlemen, having made a personal inspection of all suitable places, arrived at the unanimous conclusion “that Wellington, in Port Nicholson, was the site upon the shores of Cook Strait which presented the greatest advantages for the administration of the government of the colony.”

The seat of Government was, in accordance with the recommendations of the Commissioners, removed to Wellington in February, 1865.

Nearly all the public works of New Zealand are in the hands of the Government of the colony, and in the early days they simply kept pace with the spread of settlement. In 1870, however, a great impetus was given to the progress of the whole country by the inauguration of the “Public Works and Immigration Policy,” which provided for carrying out works in advance of settlement. Railways, roads, and water-races were constructed, and immigration was conducted on a large scale. As a consequence the population increased from 267,000 in 1871 to 501,000 in 1881, and 634,058 at the close of the year 1891, exclusive of Maoris.

SUCCESSION OF GOVERNORS OF NEW ZEALAND, AND THE DATES ON WHICH THEY ASSUMED AND RETRIED FROM THE GOVERNMENT.

Captain William Hobson, R.N., from Jan., 1840, to 10 Sept., 1842.

[Proclamation of British Sovereignty by Captain Hobson in January, 1840, and New Zealand a dependency of the Colony of New South Wales until 3rd May, 1841, at which date it was proclaimed a separate colony. From January, 1840, to May, 1841, Captain Hobson was Lieutenant-Governor of New Zealand under Sir George Gipps, Governor of New South Wales, and from May, 1841, Governor of New Zealand; the seat of Government being at Auckland, where he died in September, 1842. From the time of Governor Hobson's death, in September, 1842, until the arrival of Governor Fitzroy, in December, 1843, the Government was carried on by the Colonial Secretary, Lieutenant Shortland.]

Lieutenant Shortland, Administrator, from 10 Sept., 1812, to 26 Dec., 1843.

Captain Robert Fitzroy, R.N., from 26 Dec., 1843, to 17 Nov., 1845.

Captain Grey (became Sir George Grey. K.C.B., in 1848), from 18 Nov., 1845, to 31 Dec., 1853.

[Captain Grey held the commission as Lieutenant-Governor of the colony until the 1st January, 1848, when he was sworn in as Governor-in-Chief over the Islands of New Zealand, and as Governor of the Province of New Ulster and Governor of the Province of New Munster. After the passing of the New Zealand Constitution Act, Sir George Grey was, on the 13th September, 1852, appointed Governor of the colony, the duties of which he assumed on the 7th March, 1853. In August, 1847, Mr. E. J. Eyre was appointed Lieutenant-Governor of New Munster: he was sworn in, 28th January, 1848. On 3rd January, 1848, Major-General George Dean Pitt was appointed Lieutenant-Governor of New Ulster: he was sworn in, 14th February, 1848; died, 8th January, 1851; and was succeeded as Lieutenant-Governor by Lieutenant-Colonel Wynyard, appointed 14th April, 1851; sworn in, 26th April, 1851. The duties of the Lieutenant-Governor ceased on the assumption by Sir George Grey of his office of Governor, on the 7th March, 1853.]

Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Henry Wynyard, C.B., Administrator, from 3 Jan., 1854, to 6 Sept., 1855.

Colonel Thomas Gore Browne, C.B., from 6 Sept., 1855, to 2 Oct., 1861.

Sir George Grey, K.C.B., Administrator, from 3 Oct., 1861; Governor, from 4 Dec., 1861, to 5 Feb., 1868.

Sir George Ferguson Bowen, G.C.M.G., from 5 Feb., 1868, to 19 Mar., 1873.

Sir George Alfred Arney, Chief Justice, Administrator, from 21 Mar. to 14 June, 1873.

Sir James Fergusson, Baronet, P.C., from 14 June, 1873, to 3 Dec., 1874.

The Marquis of Normanby, P.C., Administrator, from 3 Dec., 1874; Governor, from 9 Jan., 1875, to 21 Feb., 1879.

James Prendergast, Chief Justice, Administrator, from 21 Feb. to 27 Mar., 1879.

Sir Hercules George Robert Robinson, G.C.M.G., Administrator, 27 Mar., 1879; Governor, from 17 April, 1879, to 8 Sept., 1880.

James Prendergast, Chief Justice, Administrator, from 9 Sept. to 29 Nov., 1880.

Sir Arthur Hamilton Gordon, G.C.M.G., from 29 Nov., 1880, to 23 June, 1882.

Sir James Prendergast, Chief Justice, Administrator, from 24 June, 1882, to 20 Jan., 1883.

Lieutenant-General Sir William Francis Drummond Jervois, G.C.M.G., C.B., from 20 Jan., 1883, to 22 Mar., 1889.

Sir James Prendergast, Chief Justice, Administrator, from 23 Mar. to 2 May, 1889.

The Earl of Onslow, G.C.M.G., from 2 May, 1889, to 24 Feb., 1892.

Sir James Prendergast, Chief Justice, Administrator, from 25 Feb. to 6 June, 1892.

The Earl of Glasgow, G.C.M.G., from 7 June, 1892.

MEMBERS OF THE EXECUTIVE COUNCIL OF THE COLONY OF NEW ZEALAND PREVIOUS TO THE ESTABLISHMENT OF RESPONSIBLE GOVERNMENT (NOT INCLUDING THE OFFICERS COMMANDING THE FORCES).

Willoughby Shortland, Colonial Secretary, from 3 May, 1841, to 31 Dec., 1843; succeeded by Mr. Sinclair.

Francis Fisher, Attorney-General, from 3 May to 10 Aug., 1841; succeeded by Mr. Swainson.

George Cooper, Colonial Treasurer, from 3 May, 1841, to 9 May, 1842; succeeded by Mr. Shepherd.

William Swainson, Attorney-General, from 10 Aug., 1841, to 7 May, 1856.

Alexander Shepherd, Colonial Treasurer, from 9 May, 1842, to 7 May, 1856.

Andrew Sinclair, Colonial Secretary, from 6 Jan., 1844, to 7 May, 1856.

[The holders of these three last-mentioned offices were nominated by Her Majesty as ex officio members of the Executive Council. They were not members of the General Assembly, opened for the first time 27th May, 1854, although they remained in office until the establishment of Responsible Government.]

James Edward FitzGerald, M.H.R., without portfolio, from 14 June to 2 Aug., 1854.

Henry Sewell. M.H.R., without portfolio, from 14 June to 2 Aug., 1854.

Frederick Aloysius Weld, M.H.R., without portfolio, from 14 June to 2 Aug., 1854.

Francis Dillon Bell, M.L.C., without portfolio, from 30 June to 11 July, 1854.

Thomas Houghton Bartley, M.L.C, without portfolio, from 14 July to 2 Aug., 1854.

Thomas Spencer Forsaith, M.H.R., without portfolio, from 31 Aug. to 2 Sept., 1854.

Edward Jerningham Wakefield, M.H.R., without portfolio, from 31 Aug. to 2 Sept., 1854.

William Thomas Locke Travers, M.H.R., without portfolio, 31 Aug. to 2 Sept., 1854.

James Macandrew, M.H.R., without portfolio, from 31 Aug. to 2 Sept., 1854.

| NUMBER OF PARLIAMENTS SINCE THE CONSTITUTION ACT PASSED FOR CONFERRING REPRESENTATIVE INSTITUTIONS UPON THE COLONY OF NEW ZEALAND, WITH THE DATES OF OPENING THE SESSIONS AND DATES OF CLOSING OR DISSOLUTION. | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. of Parliament. | Date of Opening of Sessions. | Date of Closing or Dissolution. |

| First Parliament | 27 May, 1854 | 9 August, 1854. |

| 31 August, 1854 | 16 September, 1854. | |

| 8 August, 1855 | 15 September, 1855. | |

| Second Parliament | 15 April, 1856 | 16 August, 1856. |

| (There was no session held in the year 1857.) | ||

| 10 April, 1858 | 21 August, 1858. | |

| (There was no session held in the year 1859.) | ||

| 30 July, 1860 | 5 November, 1860. | |

| Third Parliament | 3 June, 1861 | 7 September, 1861. |

| 7 July, 1862 | 15 September, 1862. | |

| 19 October, 1863 | 14 December, 1863. | |

| 24 November, 1864 | 13 December, 1864. | |

| 26 July, 1865 | 30 October, 1865. | |

| Fourth Parliament | 30 June, 1866 | 8 October, 1866. |

| 9 July, 1867 | 10 October, 1867. | |

| 9 July, 1868 | 20 October, 1868. | |

| 1 June, 1869 | 3 September, 1869. | |

| 14 June, 1870 | 13 September, 1870. | |

| Fifth Parliament | 14 August, 1871 | 16 November, 1871. |

| 16 July, 1872 | 25 October, 1872. | |

| 15 July, 1873 | 3 October, 1873. | |

| 3 July, 1874 | 31 August, 1874. | |

| 20 July, 1875 | 21 October, 1875. | |

| Sixth Parliament | 15 June, 1876 | 31 October, 1876. |

| 19 July, 1877 | 10 December, 1877. | |

| 26 July, 1878 | 2 November, 1873. | |

| 11 July, 1879 | 15 August, 1879. | |

| Seventh Parliament | 24 September, 1879 | 19 December, 1879. |

| 28 May, 1880 | 1 September, 1880. | |

| 9 June, 1881 | 24 September, 1881. | |

| Eighth Parliament | 18 May, 1882 | 15 September, 1882. |

| 14 June, 1883 | 8 September, 1883. | |

| 5 June, 1884 | 24 June, 1884. | |

| Ninth Parliament | 7 August, 1884 | 10 November, 1884. |

| 11 June, 1885 | 22 September, 1885. | |

| 13 May, 1886 | 18 August, 1886. | |

| 26 April, 1887 | 15 July, 1887. | |

| Tenth Parliament | 6 October, 1887 | 23 December, 1887. |

| 10 May, 1888 | 31 August, 1888. | |

| 20 June, 1889 | 19 September, 1889. | |

| 19 June, 1890 | 3 October, 1890. | |

| Eleventh Parliament | 27 January, 1891 | 31 January, 1891. |

| 11 June, 1891 | 5 September, 1891. | |

| 23 June, 1892 | ||

| SINCE THE ESTABLISHMENT OF RESPONSIBLE GOVERNMENT IN NEW ZEALAND IN 1856. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Name of Ministry. | Assumed Office. | When retired. |

| 1. Bell-Sewell | 7 May, 1856 | 20 May, 1856. |

| 2. Fox | 20 May, 1856 | 2 June, 1856. |

| 3. Stafford | 2 June, 1856 | 12 July, 1861. |

| 4. Fox | 12 July, 1861 | 6 August, 1862. |

| 5. Domett | 6 August, 1862 | 30 October, 1863. |

| 6. Whitaker-Fox | 30 October, 1863 | 24 November, 1864. |

| 7. Weld | 24 November, 1864 | 16 October, 1865. |

| 8. Stafford | 16 October, 1865 | 28 Tune, 1869. |

| 9. Fox | 28 June, 1869 | 10 September, 1872. |

| 10. Stafford | 10 September, 1872 | 11 October, 1872. |

| 11. Waterhouse | 11 October, 1872 | 3 March, 1873. |

| 12. Fox | 3 March, 1873 | 8 April, 1873. |

| 13. Vogel | 8 April, 1873 | 6 July, 1875. |

| 14. Pollen | 6 July, 1875 | 15 February, 1876. |

| 15. Vogel | 15 February, 1876 | 1 September, 1876. |

| 16. Atkinson | 1 September, 1876 | 13 September, 1876. |

| 17. Atkinson (reconstituted) | 13 September, 1876 | 13 October, 1877. |

| 18. Grey | 15 October, 1877 | 8 October, 1879. |

| 19. Hail | 8 October, 1879 | 21 April, 1882. |

| 20. Whitaker | 21 April, 1882 | 25 September, 1883. |

| 21. Atkinson | 25 September, 1883 | 16 August, 1884. |

| 22. Stout-Vogel | 16 August, 1884 | 28 August, 1884. |

| 23. Atkinson | 28 August, 1884 | 3 September, 1884. |

| 24. Stout-Vogel | 3 September, 1884 | 8 October, 1887. |

| 25. Atkinson | 8 October, 1887 | 24 January, 1891. |

| 26. Ballance | 24 January, 1891 | Still in office. |

| Name of Premier. | Date of Assumption of Office. | Date of Retirement from Office. |

|---|---|---|

| Henry Sewell | 7 May, 1856 | 20 May, 1856. |

| William Fox | 20 May, 1856 | 2 June, 1856. |

| Edward William Stafford | 2 June, 1850 | 12 July, 1861. |

| William Fox | 12 July, 1861 | 6 August, 1862. |

| Alfred Domett | 6 August, 1862 | 30 October, 1863. |

| Frederick Whitaker | 30 October, 1863 | 24 November, 1864. |

| Frederick Aloysius Weld | 24 November, 1864 | 16 October, 1865. |

| Edward William Stafford | 16 October, 1865 | 28 June, 1869. |

| William Fox | 28 June, 1869 | 10 September, 1872. |

| Hon. Edward William Stafford | 10 September, 1872 | 11 October, 1872. |

| George Marsden Waterhouse | 11 October, 1872 | 3 March, 1873. |

| Hon. William Fox | 3 March, 1873 | 8 April, 1873. |

| Hon. Julius Vogel, C.M.G. | 8 April, 1873 | 6 July, 1875. |

| Daniel Pollen, M.L.C. | 6 July, 1875 | 15 February, 1876. |

| Sir Julius Vogel, K.C.M.G. | 15 February, 1876 | 1 September, 1876. |

| Harry Albert Atkinson | 1 September, 1876 | 13 September, 1876. |

| Harry Albert Atkinson (Ministry re-constituted) | 13 September, 1876 | 13 October, 1877. |

| Sir George Grey, K.C.B. | 15 October, 1877 | 8 October, 1879. |

| Hon. John Hall | 8 October, 1879 | 21 April, 1882. |

| Frederick Whitaker, M.L.C. | 21 April, 1882 | 25 September, 1883. |

| Harry Albert Atkinson | 25 September, 1883 | 16 August, 1884. |

| Robert Stout | 16 August, 1884 | 28 August, 1884. |

| Harry Albert Atkinson | 28 August, 1884 | 3 September, 1884. |

| Sir Robert Stout, K.C.M.G. | 3 September, 1884 | 8 October, 1887. |

| Sir Harry Albert Atkinson, K.C.M.G. | 6 October, 1887 | 24 January, 1891. |

| John Ballance | 24 January, 1891 |

| Name of Speaker. | Date of Appointment. | Date of Retirement. |

|---|---|---|

| Hon. William Swainson | 16 May, 1854 | 8 August, 1855. |

| Hon. Frederick Whitaker | 8 August, 1855 | 12 May, 1856. |

| Hon. Thomas Houghton Bartley | 12 May, 1856 | 1 July, 1868. |

| Hon. Sir John Larkins Cheese Richardson | 1 July, 1868 | 14 June, 1879. |

| Hon. Sir William Fitzherbert, K.C.M.G. | 14 June, 1879 | 23 January, 1891. |

| Hon. Sir Harry Albert Atkinson, K.C.M.G. | 23 January, 1891 | 28 June, 1892. |

| Hon. Henry John Miller | 8 July, 1892 |

| Name of Speaker. | Dates of Election. | Date of Retirement. |

|---|---|---|

| Sir Charles Clifford | 26 May, 1854 | |

| 15 April, 1856 | 3 June, 1861. | |

| Sir David Monro | 3 June, 1861 | |

| 30 June, 1866 | 14 August, 1871. | |

| Sir Francis Dillon Bell | 14 August, 1871 | 15 June, 1876. |

| Sir William Fitzherbert, K.C.M.G. | 15 June, 1876 | 13 June, 1879. |

| Sir George Maurice O'Rorke, Knt. Bach. | 11 July, 1879 | |

| 24 September, 1879 | ||

| 18 May, 1882 | ||

| 7 August, 1884 | ||

| 6 October, 1887 | 22 January, 1891. | |

| Major William Jukes Steward | 22 January, 1891 |

(DOWNING STREET, S.W., LONDON), WITH DATES OF APPOINTMENT.

Secretary of State—The Right Hon. Lord Knutsford, 14 Jan., 1887; created Baron Knutsford, 1888. Under-Secretaries—The Right Hon. Baron Henry de Worms, M.P., 20 Feb., 1888; Hon. Robert H. Meade, C.B., 1 Feb., 1892. Assistant Under-Secretaries —John Bramston, D.C.L., C.B., 30 June, 1876; Edward Wingfield, B.C.L., C.B., 19 July, 1878. Edward Fairfield, C.M.G., 1 Feb., 1892. Private Secretary to the Secretary of State—W. A. Baillie Hamilton, C.M.G. Assistant Private Secretaries—H. W. Just, B.A., and W. C. Bridgeman.

Bell, Sir Francis Dillon, K.B., 1873; K.C.M.G., 1881; C.B., 1886.

Buckley, Sir Patrick Alphonsus, K.C.M.G., 1892.

Buller, Sir Walter Lawry, F.R.S., C.M.G., 1875; K.C.M.G., 1886.

FitzGerald, James Edward, Esq., C.M.G., 1870.

Fox, Sir William, K.C.M.G., 1879.

Grace, Morgan Stanislaus, Esq., C.M.G.

Grey, Sir George, K.C.B., 1818.

Hall, Sir John, K.C.M.G., 1882.

Hector, Sir James, F.R.S., C.M.G., 1875; K.C.M.G., 1887.

Larnach, William James Mudie, Esq., C.M.G, 1879.

O'Rorke, Sir George Maurice, Knt. Bach., 1880.

Prendergast, Sir James, Knt. Bach., 1881.

Richardson, Hon. Edward, C.M.G., 1879.

Roberts, John, Esq., C.M.G.

Stafford, Sir Edward William, K.C.M.G., 1879; G.C.M.G., 1887.

Stout, Sir Robert, K.C.M.G., 1886.

Vogel, Sir Julius, C.M.G., 1872; K.C.M.G., 1875.

Whitmore, Colonel Sir George Stoddart, C.M.G., 1869; K.C.M.G., 1882.

EX-MINISTERS AND MINISTERS ALLOWED TO RETAIN THE TITLE OF “HONOURABLE” WITHIN THE COLONY.

Messrs. E. W. Stafford, J. Hall, and Colonel T. M. Haultain, gazetted March 23, 1870; Messrs. W. Fox, Julius Vogel, C.M.G., and W. Gisborne, gazetted February 13, 1873; Mr. W. H. Reynolds, by despatch from Secretary of State, May 11, 1876; Mr. E. Richardson, gazetted May 31, 1877; Messrs. W. Rolleston, John Bryce, K, Oliver, T. Dick, and W. W. Johnston, gazetted December 24, 1884; Sir Robert Stout, K.C.M.G., Sir Julius Vogel, K.C.M.G., Messrs. E. Richardson, J. Ballance, J. A. Tole, P. A. Buckley, W. H. Reynolds, and W. J. M. Larnach, C.M.G., gazetted February 2, 1888; Messrs. E. Mitchelson, T. Fergus, G. F. Richardson, and T. W. Hislop, gazetted June 4, 1891.

CONSULS OF FOREIGN COUNTRIES RESIDING IN, OR WITH JURISDICTION OVER, NEW ZEALAND IN THE YEAR 1892.

Netherlands.—Chevalier Daniel Ploos Van Amstel, Melbourne, Consul-General; Charles John Johnston, Wellington, Consul; Edward Bowes Cargill, Dunedin, and David Boosie Cruickshank, Auckland, Vice-Consuls.

Belgium.—Gustave Beckx, Melbourne, Consul-General; Charles John Johnston, Wellington, Alexander Beck, Christchurch, and Arthur Masy, Auckland, Consuls.

Italy.—Cavaliere Nicola Squitti, Barone de Palermiti e Guarna, Melbourne, Consul; Alexander Cracroft Wilson, Christchurch, George Fisher, Wellington, Edward Bowes Cargill, Dunedin, Dr. Francesco Rosetti, Hokitika, Geraldo Guiseppe Perotti, Greymouth, and Patrick Comiskey, Auckland, Consular Agents.

German Empire.—A. Pelldram, Sydney, Consul-General; John Hamann, Dunedin (acting), William Henry Simms, Christchurch, Friedrich August Krull, Wanganui, Hermann Brown, Auckland, Consuls; Augustus Friedrich Castendyk, Wellington, Vice-Consul.

France.—Felix Jacques de Lostalot de Bachoué, Wellington Vice-Consul; David Boosie Cruickshank, Auckland, Percival Clay Neill, Dunedin, and Hon. Edmund William Parker, Christchurch, Consular Agents.

Sweden and Norway.—Fortunatus Evelyn Wright, Christchurch, and Edward Pearce, Wellington, Consuls; Harlan Page Barber, Auckland, Vice-Consul; Edmund Quick, Dunedin, Consular Agent.

Denmark.—Edward Valdemar Johansen, Auckland, Consul; Edmund Quick, Dunedin, and Emil Christian Skog, Christchurch, Vice-Consuls.

Spain.—Don Francisco Arenas Y. Bonet, Christchurch, Vice-Consul.

Portugal.—John Duncan, Wellington, Consul; Henry Rees George, Auckland, and Edmund Quick, Dunedin, Vice-Consuls.

United States.—O. M. Spencer, Melbourne, Consul-General; John Darcy Conolly, Auckland, Consul (for New Zealand); Francis Hopes Webb, Auckland, Vice-Consul; Albert Cuff, Christchurch, Henry Stephenson, Russell, Robert Wyles, Mongonui, William Hort Levin, Wellington, and Henry Driver, Dunedin, Consular Agents.

Chili—William Henry Eldred, Sydney, Consul-General; David Boosie Cruickshank, Auckland, Consul; Edmund Quick, Dunedin, Consular Agent.

Argentine Republic.—John Lee Leesmith, Dunedin, Consul.

Columbia.—Thomas P. Fallon, Melbourne, Consul-General.

Hawaiian Islands.—Henry Driver, Dunedin, and James Cruickshank, Auckland, Consuls.

Table of Contents

W. B. Perceval, Esq., Westminster Chambers, 13, Victoria Street, S.W. Secretary—Walter Kennaway, Esq., C.M.G.

New South Wales.—Sir Saul Samuel, K.C.M.G., C.B., Westminster Chambers, 9, Victoria Street, S.W. Secretary—S. Yardley, Esq.

Victoria.—The Hon. James Munro, Victoria Chambers, 15, Victoria Street, S.W. Secretary—John Cashel Hoey, Esq., C.M.G.

South Australia.—Sir John Cox Bray, K.C.M.G., Victoria Chambers, 15, Victoria Street, S.W. Assistant, Samuel Deering, Esq.

Queensland.—Sir James E. Garrick, K.C.M.G., Q.C., Westminster Chambers, 1, Victoria Street, S.W. Charles Shortt Dicken, Esq., C.M.G.

Tasmania.—Sir Edward N. Coventry Braddon, K.C.M.G., Westminster Chambers, 5, Victoria Street, S.W.

Western Australia.—Crown Agents for the Colony—Sir Montagu P. Ommaney, K.C.M.G., and Ernest E. Blake, Esq., Colonial Office Buildings, Downing Street, S.W.

OFFICES: DOWNING STREET, S.W.; AND 1, TOKENHOUSE BUILDINGS, E.C., LONDON.

Crown Agents—Sir Montagu Frederick Ommaney, K.C.M.G., and Ernest Edward Blake. Accountant—J. W. Leonard. Registrar—J. Chadwick. Chief Cashier—L. Adams. Engineering Clerk and Head of Contract Branch—T. R. Marsh, M.A.

GLASGOW, His Excellency the Right Honourable David, Earl of, G.C.M.G., a captain of the royal navy, who served in the White Sea during the Russian war, and in the Chinese war of 1857, and retired in 1878; born 1833; married, in 1873, Dorothea Thomasina, daughter of Sir Edward Hunter-Blair; appointed February 24, and assumed office June 7, 1892, as Governor and Commander-in-Chief in and over Her Majesty's Colony of New Zealand and its dependencies, and Vice-Admiral of the same. Salary, £5,000. Residences: Government House, Wellington; and Government House, Auckland.

Private Secretary—Colonel Pat Boyle (late Grenadier Guards).

Assistant Private Secretary—George Maurice Gillington.

Aides-de-camp—Reginald Stanley Hunter-Blair (Captain, Gordon Highlanders) and Edward Francis Clayton (Lieutenant, Scots Guards).

ADMINISTRATOR OF THE GOVERNMENT—A dormant commission empowers the Chief Justice of the colony for the time being to administer the Government in case of the death, incapacity, or removal, or departure of the Governor.

Hon. J. Ballance, Premier, Colonial Treasurer, and Commissioner of Trade and Customs.

Hon. Sir P. A. Buckley, M.L.C., K.C.M.G., Attorney-General and Colonial Secretary.

Hon. W. P. Reeves, Minister of Education, Commissioner of Stamp Duties, and Minister of Labour.

Hon. R. J. Seddon, Minister for Public Works, Minister of Mines, Minister of Defence, and Minister of Marine.

Hon. J. McKenzie, Minister of Lands and Immigration and Minister of Agriculture.

Hon. A. J. Cadman, Minister of Native Affairs and Minister of Justice.

Hon. J. G. Ward, Postmaster-General and Telegraph Commissioner.

Hon. J. Carroll (without portfolio), representing the Native race.

[The above Ministers are also members of the Cabinet.]

Clerk of Executive Council—Alexander James Willis.

Table of Contents

- LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL.

- ROLL OF MEMBERS

OF THE HONOURABLE THE

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL,

Stating the Provincial District in which Members reside, and the Date of Writ of Summons. - HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES.

- ROLL OF MEMBERS

OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES,

With the Name of the District for which they are elected, and the Date of Notification of Return of Writ.