Table of Contents

LIST OF PAPERS AND THEIR AUTHORS.

| INTRODUCTION | The EDITOR | Page 13 |

| DISCOVERY AND EARLY SETTLEMENT OF THE COLONY | The Hon. W. Fox, M.H.R. | 17 |

| THE NATIVE RACE | The Hon. Sir D. MCLEAN,K.C.M.G., M.H.R., Native Minister | 26 |

| PRESENT FORM OF GOVERNMENT | The Hon. W. GISBORNE, Commissioner of Annuities | 32 |

| CLIMATE, AND MINERAL AND AGRICULTURAL RESOURCES | Dr. HECTOR, Colonial Geologist. | 35 |

| ANIMAL AND VEGETABLE PRODUCTIONS | Mr. TRAVERS | 40 |

| SOME OF THE INSTITUTIONS OF THE COLONY | Mr. WOODWARD, Public Trustee. | 43 |

| NOTES, STATISTICAL, COMMERCIAL, AND INDUSTRIAL | Ditto | 54 |

| LATEST STATISTICS | Mr. BROWN, Registrar-General | 68 |

| Mr. BATKIN, Secretary to the Treasury | 68 | |

| Mr. SEED, Secretary to the Customs | 68 | |

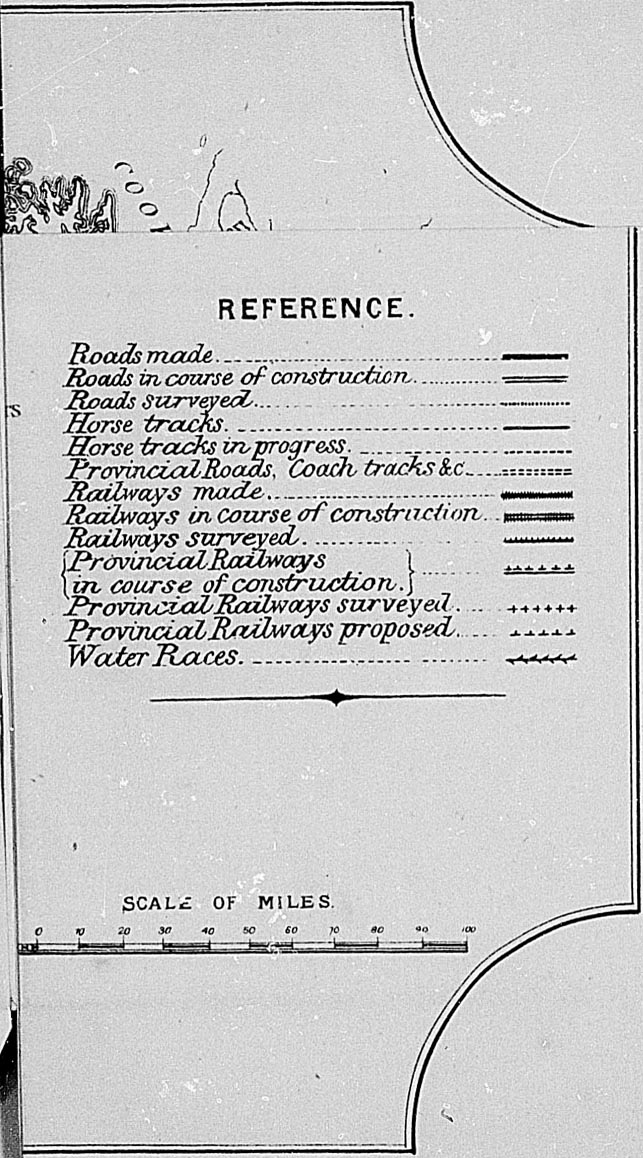

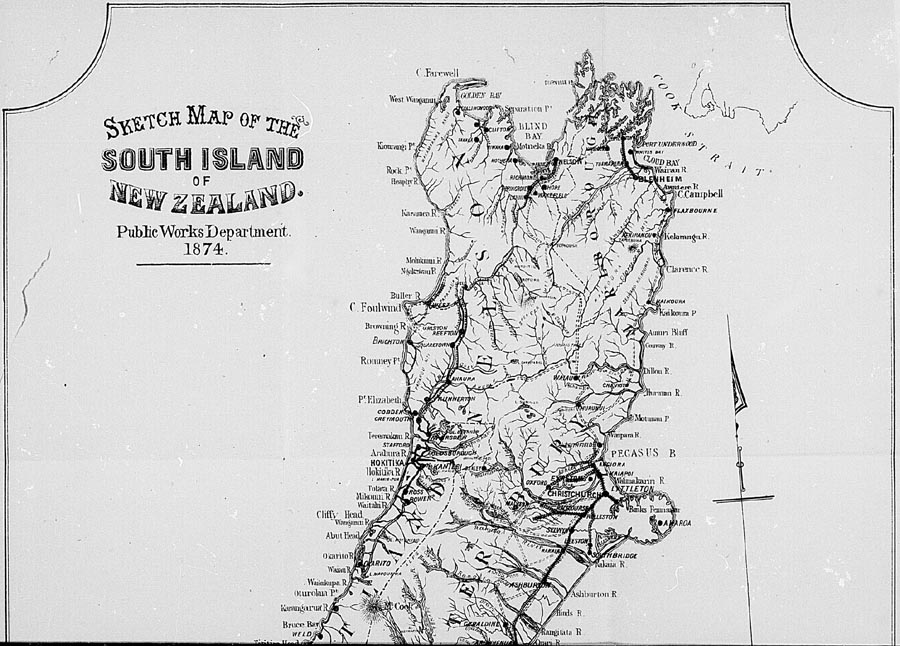

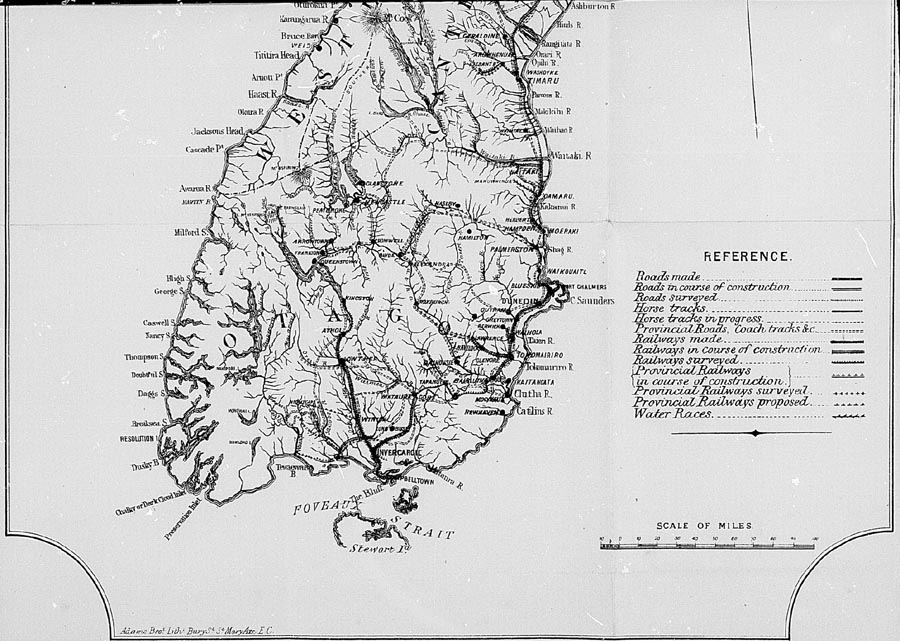

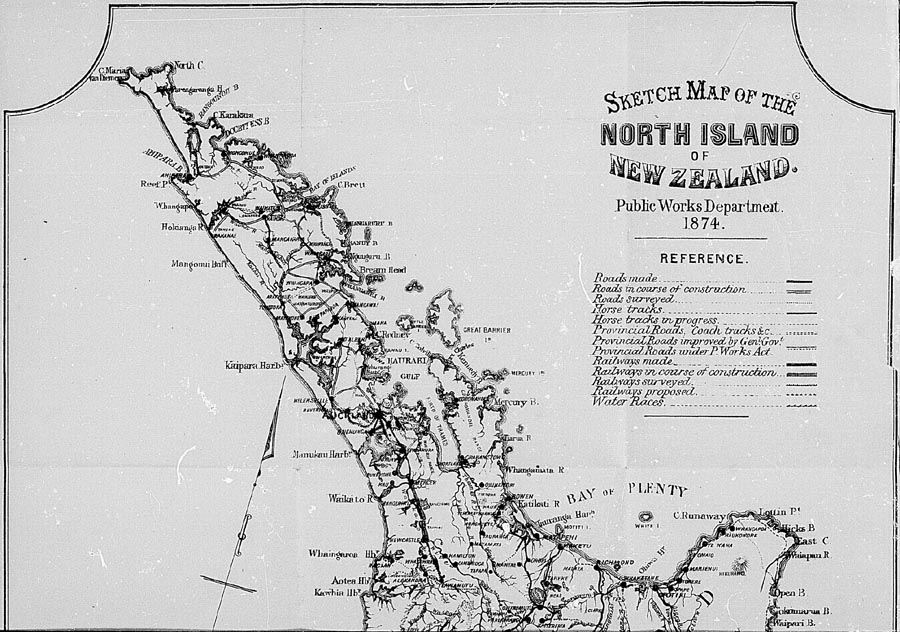

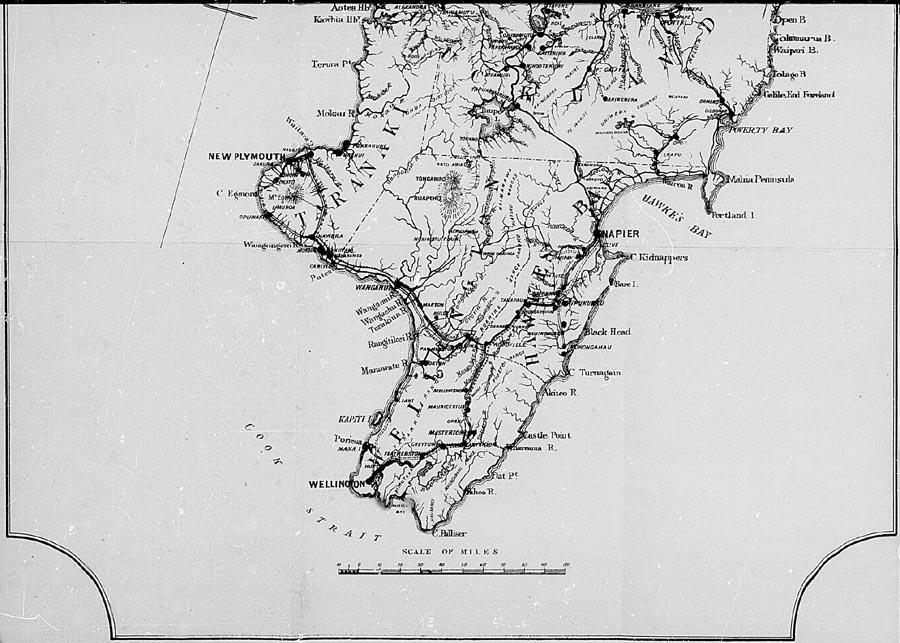

| PUBLIC WORKS DEPARTMENT | Mr. KNOWLES, Under Secretary for Public Works | 75 |

| IMMIGRATION DEPARTMENT | Mr. HAUGHTON, Under Secretary for Immigration | 76 |

| OFFICIAL DIRECTORY | Mr. COOPER, the Under Secretary | 85 |

| OTAGO. — Furnished by the Superintendent of Otago, Mr. MACANDREW, M.H.R. | Prepared by Mr. J. MCINDOE | 92 |

| CANTERBURY.—Furnished by the Superintendent of Canterbury, Mr. ROLLESTON, M.H.R. | Prepared by Mr. W. M. MASKELL | 121 |

| WESTLAND.—Furnished by the Superintendent of Westland, the Hon. J. A. BONAR, M.L.C. | Prepared by Mr. J. DRISCOLL | 157 |

| MARLBOROUGH.—Furnished by the Superintendent of Marlborough, Mr. SEYMOUR, M.H.R., Chairman of Committees of the House of Representatives. | Prepared by Mr. A. MASKELL | 164 |

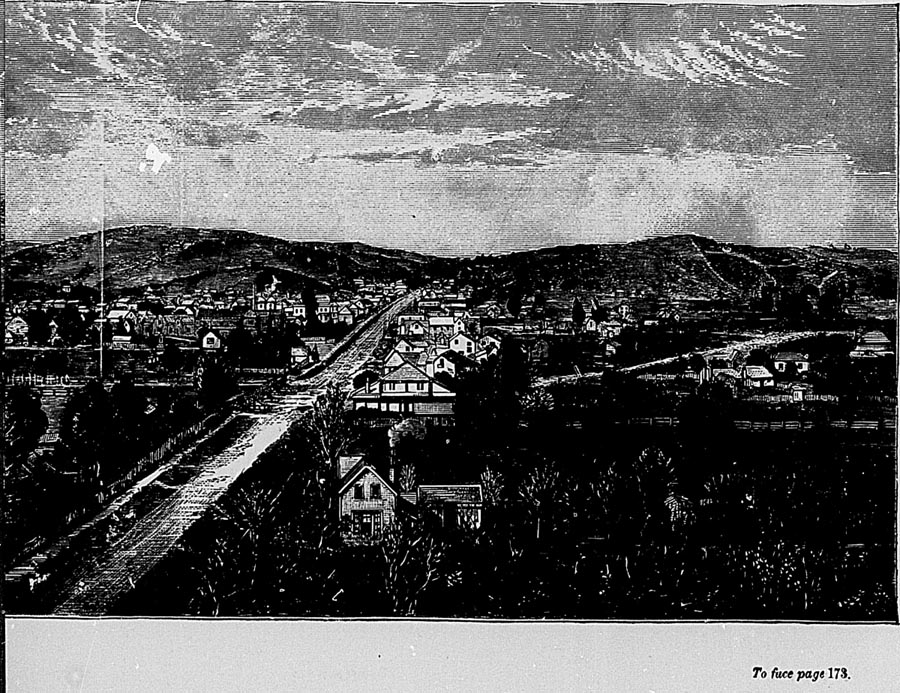

| NELSON.—Furnished by the Superintendent of Nelson, Mr. CURTIS, M.H.R. | Prepared by Mr. C. ELLIOTT | 173 |

| WELLINGTON.—Furnished by the Superintendent of Wellington, the Hon. W. FITZHERBERT, M.H.R., C.M.G. | Prepared by Mr. H. ANDERSON | 185 |

| THE MANCHESTER "SPECIAL" SETTLEMENT | Prepared by Mr. A. F. HALCOMBE | 215 |

| HAWKE'S BAY.—Furnished by the Superintendent of Hawke's Bay, Mr. ORMOND, M.H.R. | Prepared by Mr. W. W. CARLILE | 218 |

| TARANAKI.—Furnished by the Superintendent of Taranaki, Mr. CARRINGTON, M.H.R. | Prepared by Mr. C. D. WHITCOMBE | 227 |

| AUCKLAND.—Furnished by the Superintendent of Auckland, Mr. WILLIAMSON, M.H.R. | Prepared by the Rev. R. KIDD, LL.D., assisted by Mr. T. W. LEYS. | 243 |

Table of Contents

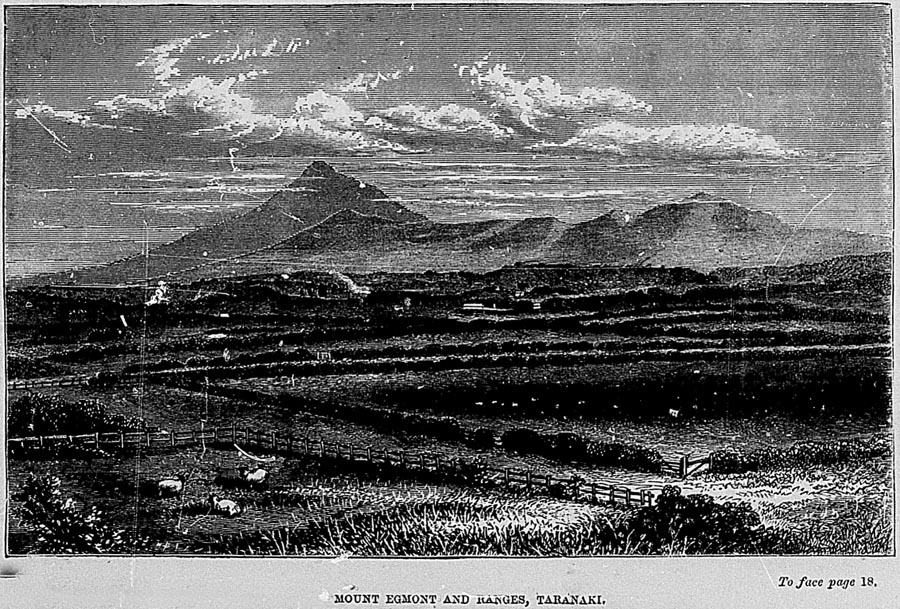

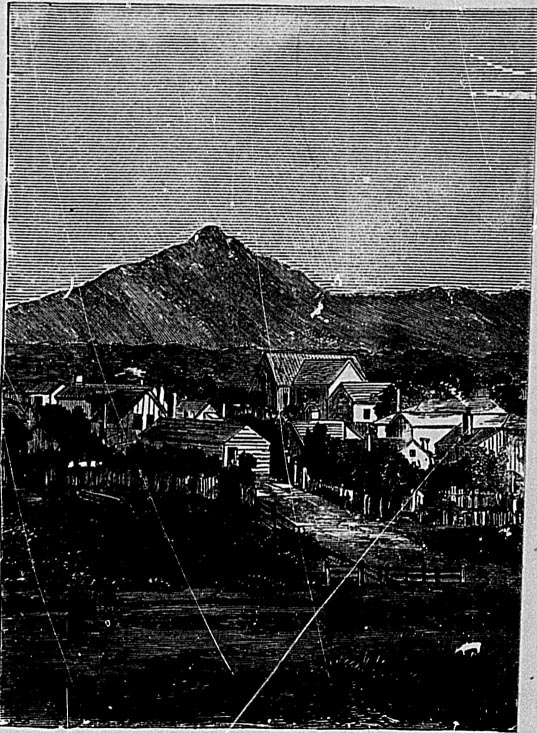

| MOUNT EGMONT AND RANGES, TARANAKI | 19 |

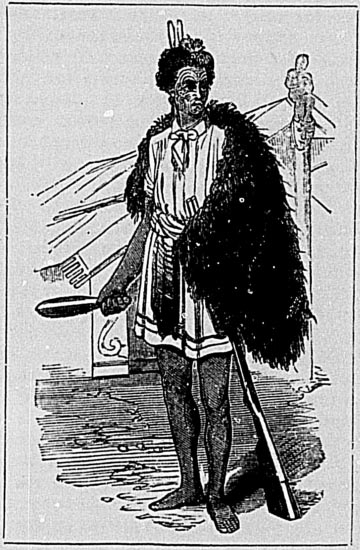

| SKETCH OF A MAORI CHIEF | 30 |

| GOVERNMENT HOUSE, WELLINGTON | 33 |

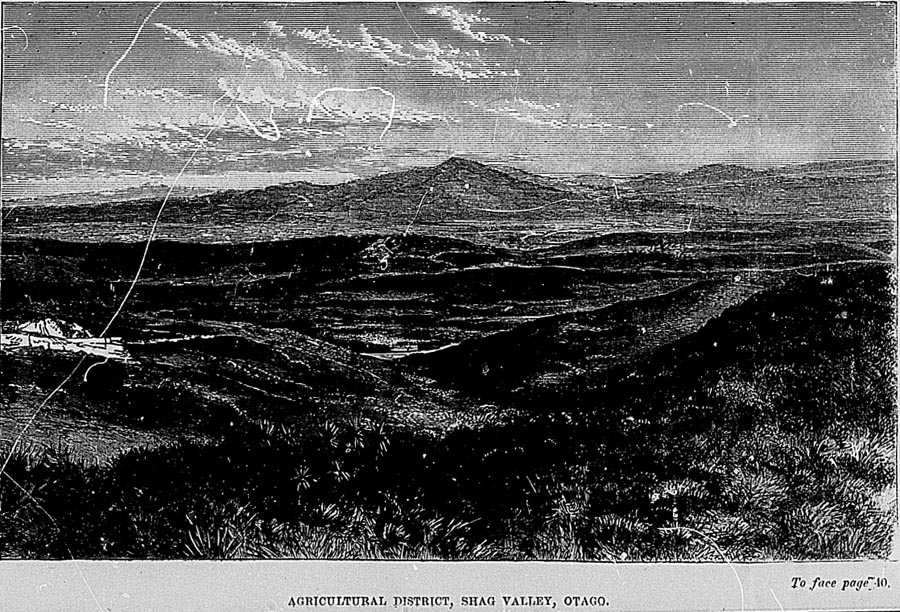

| AGRICULTURAL DISTRICT, SHAG VALLEY, OTAGO | 41 |

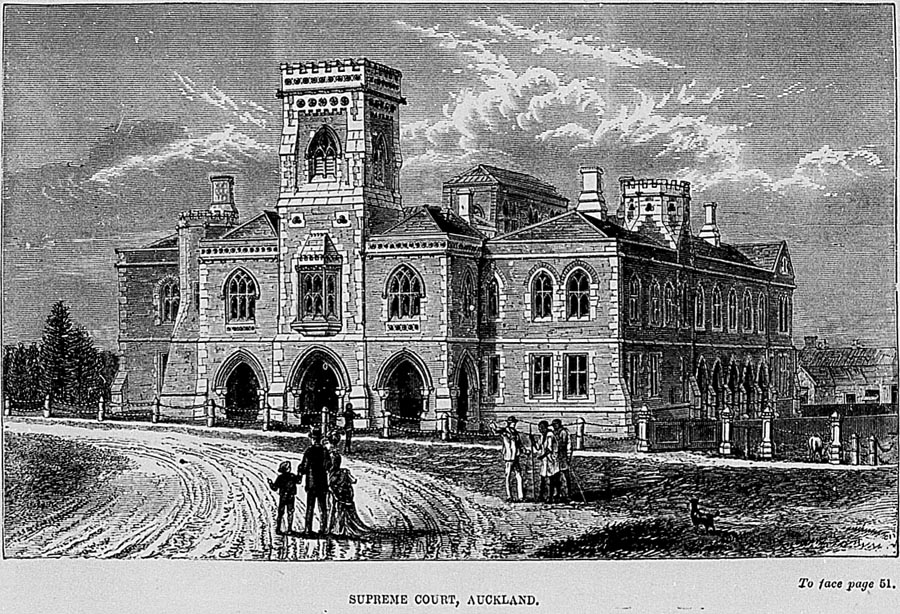

| SUPREME COURT, AUCKLAND | 51 |

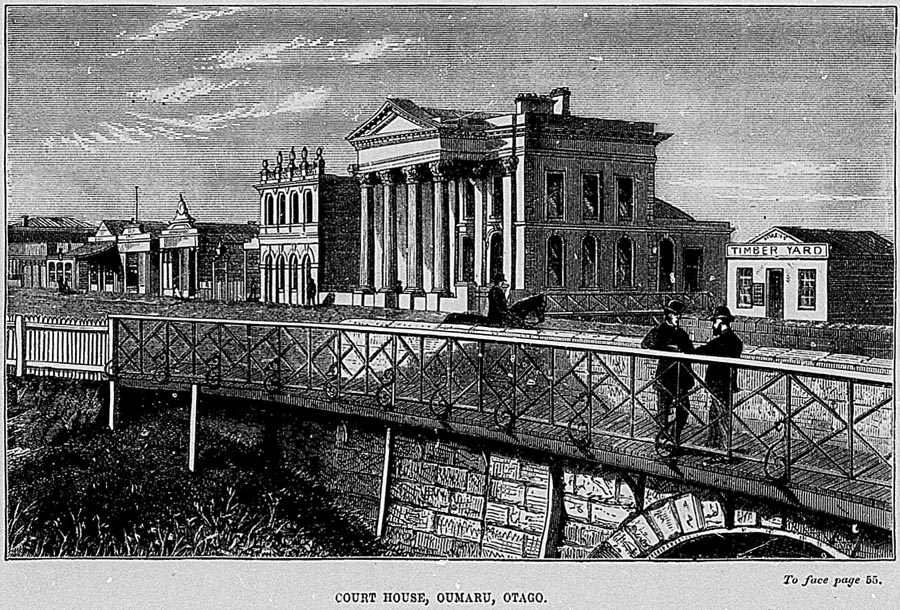

| COURT HOUSE, OAMARU, OTAGO | 54 |

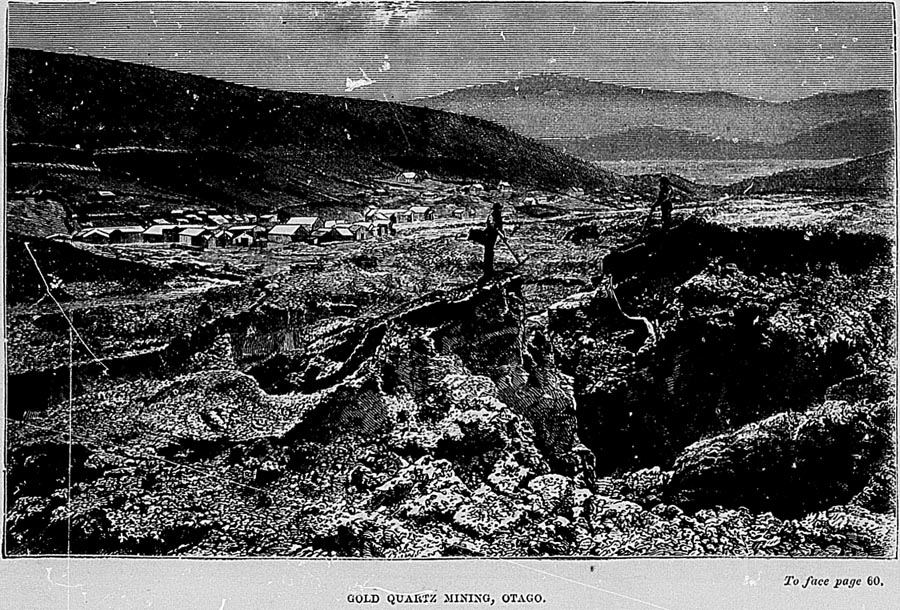

| GOLD QUARTZ MINING | 61 |

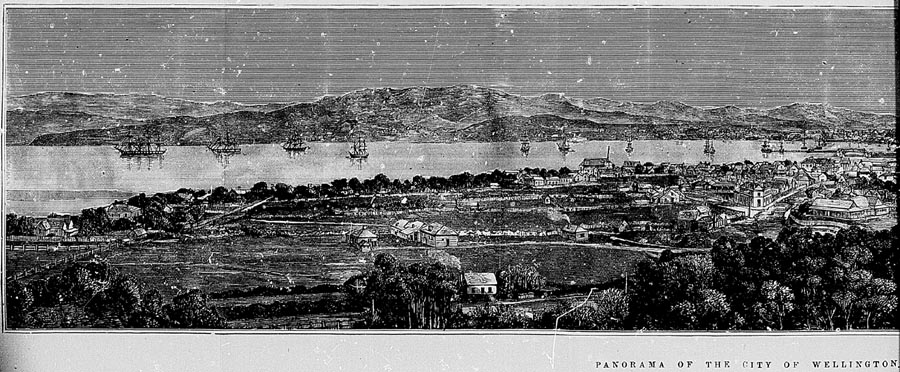

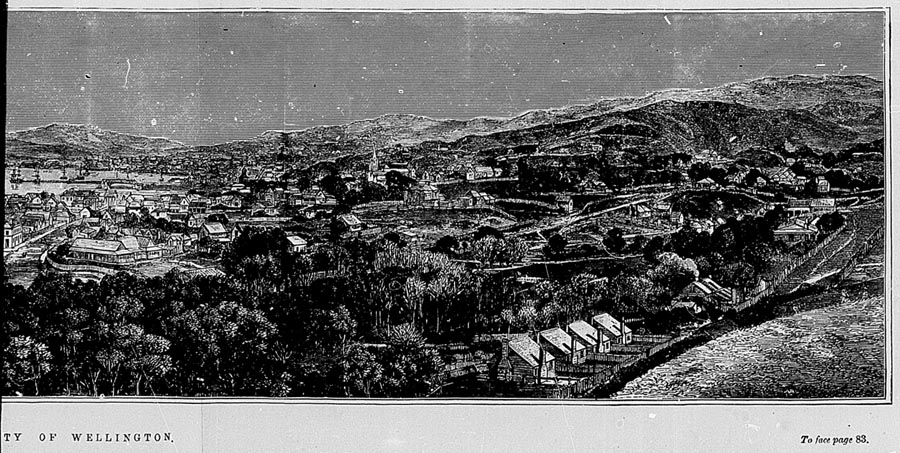

| PANORAMA OF THE CITY OF WELLINGTON | 84 |

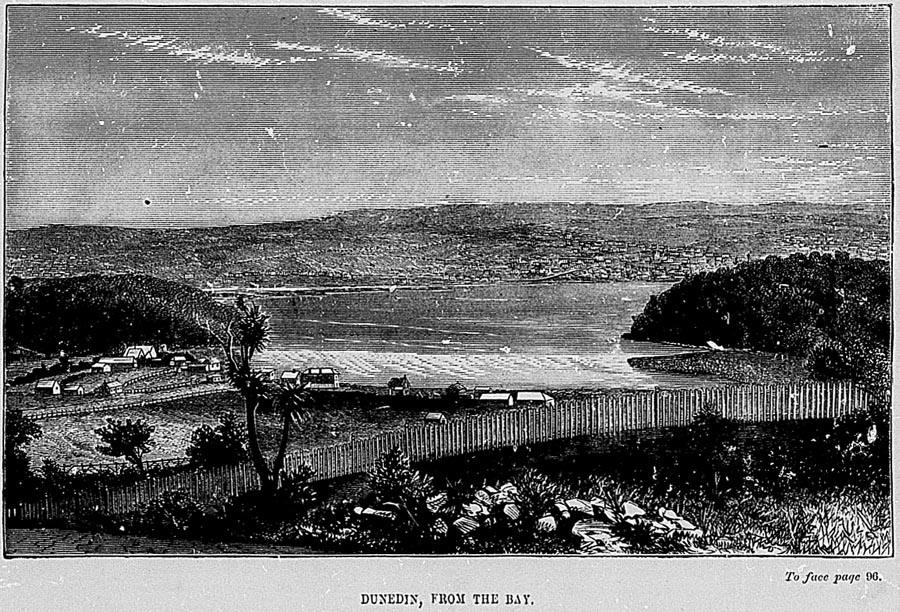

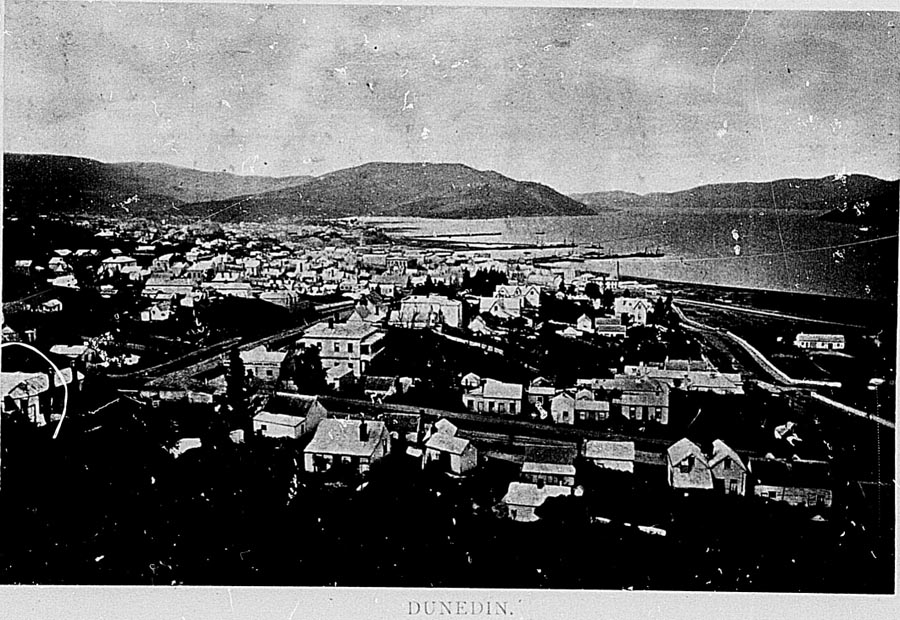

| DUNEDIN, FROM THE BAY | 97 |

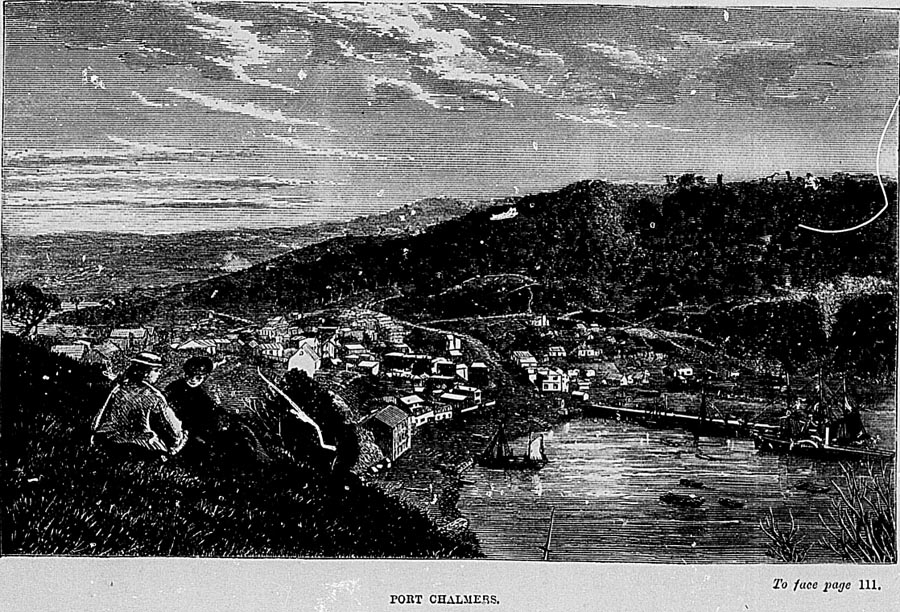

| PORT CHALMERS | 110 |

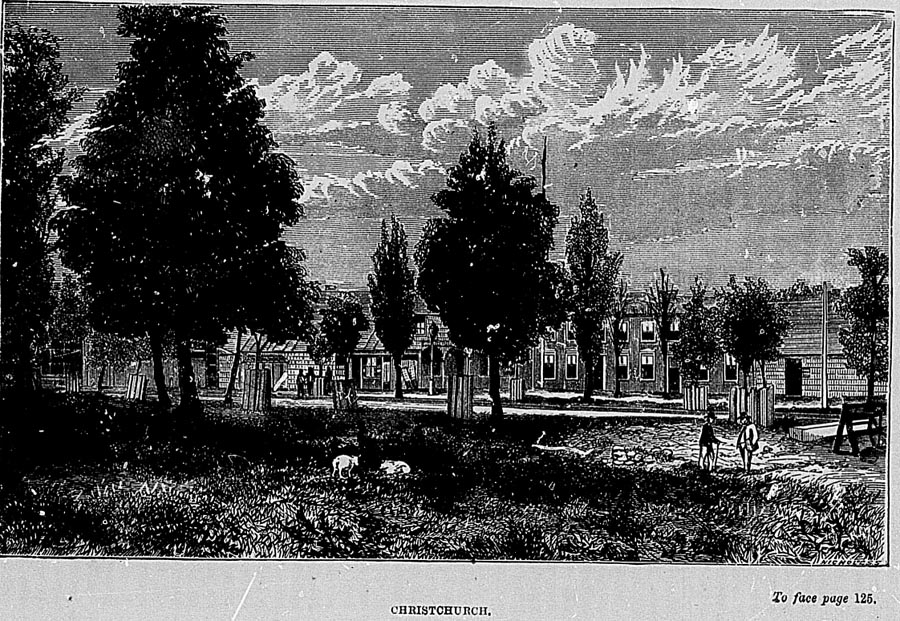

| CHRISTCHURCH | 124 |

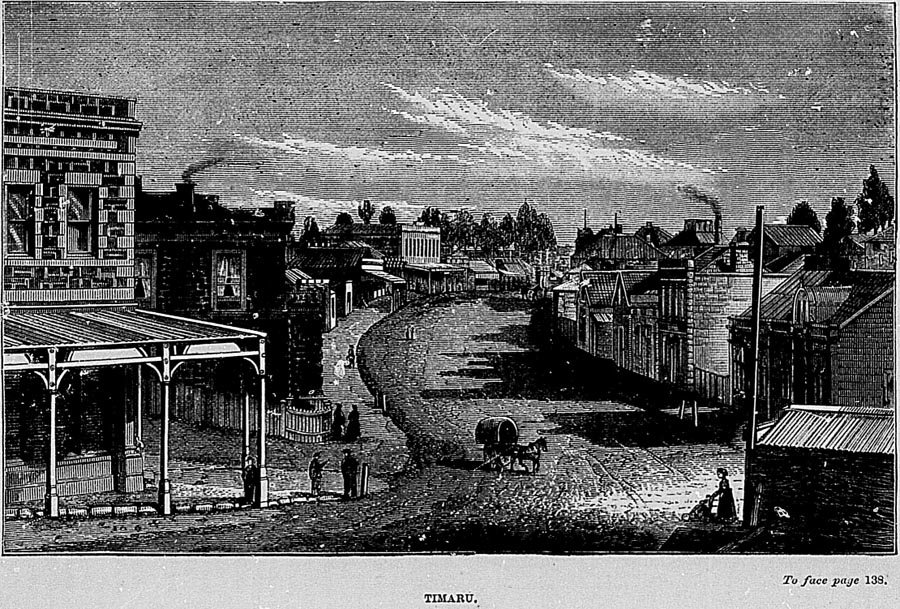

| TIMARU | 139 |

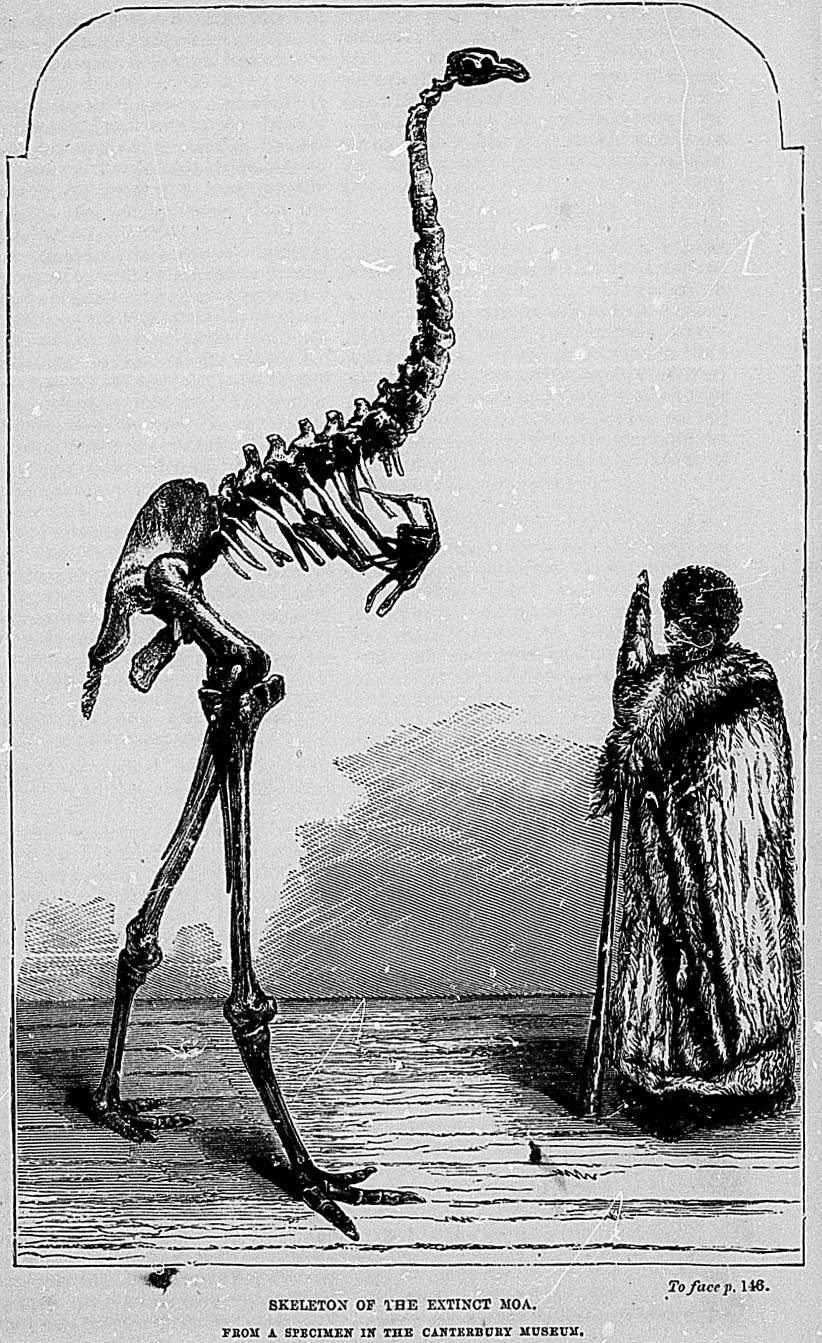

| SKELETON OF THE EXTINCT MOA | 145 |

| HOKITIKA RIVER, FROM THETOWN OF HOKITIKA | 156 |

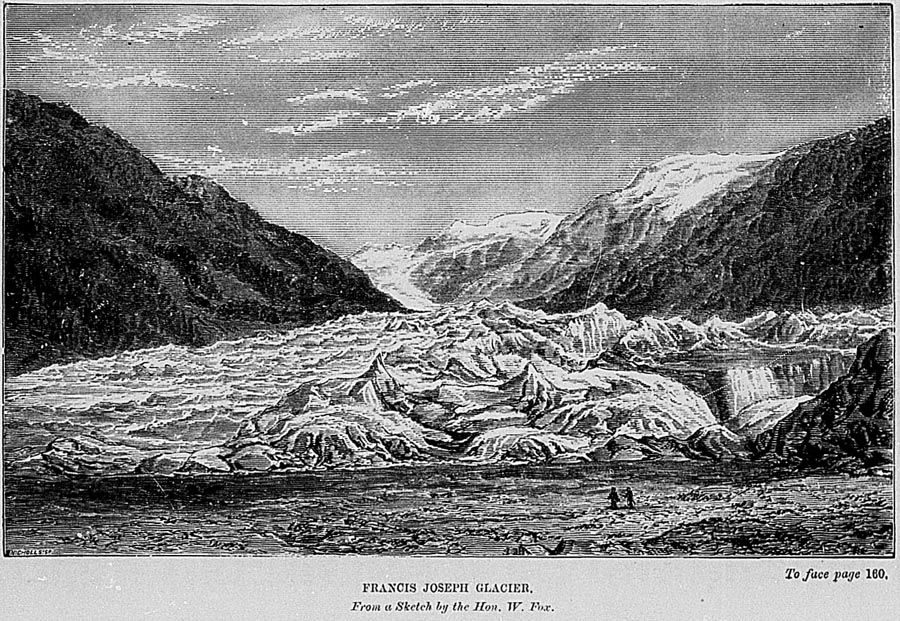

| FRANCIS JOSEPH GLACIER. From a Sketch by the Hon. W. Fox | 161 |

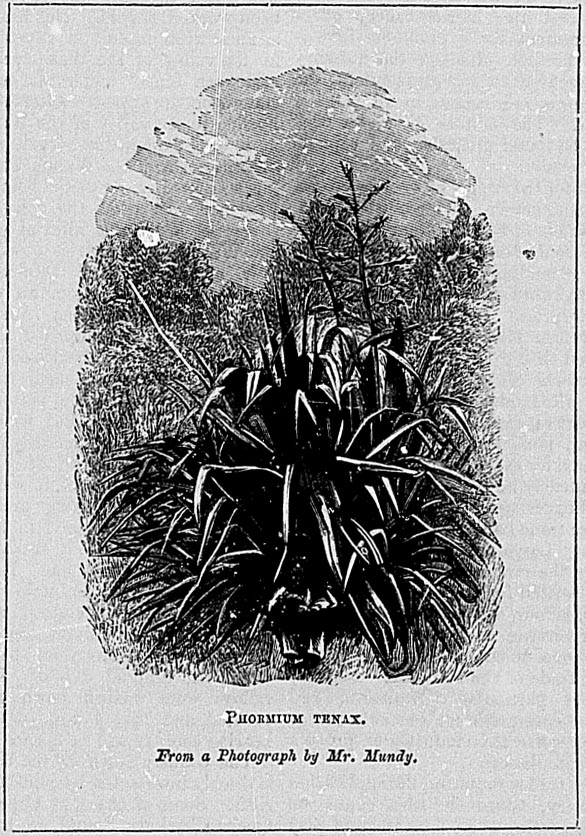

| PHORMIUM TENAX, OR NEW ZEALAND FLAX. From a Photograph by Mr. MUNDY | 169 |

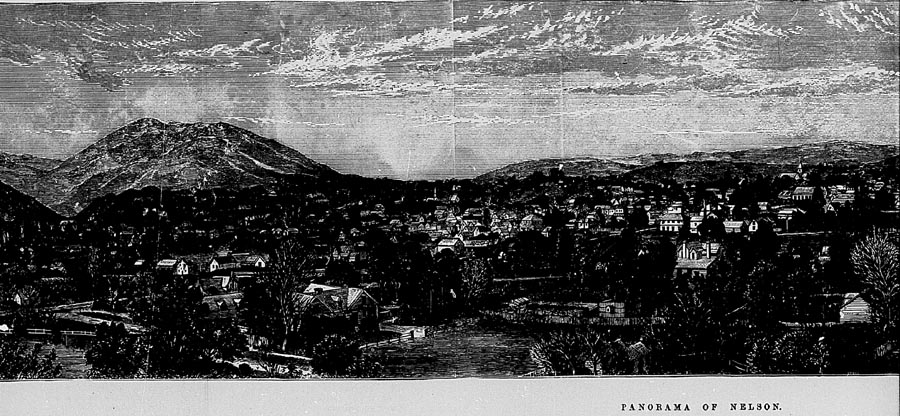

| PANORAMA OF THE CITY OF NELSON | 173 |

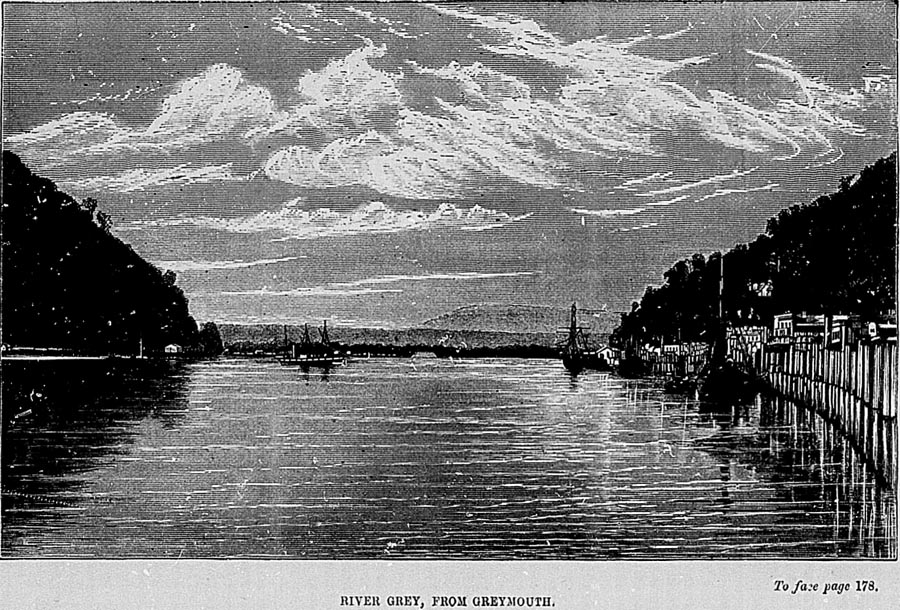

| RIVER GREY, FROM GREYMOUTH | 179 |

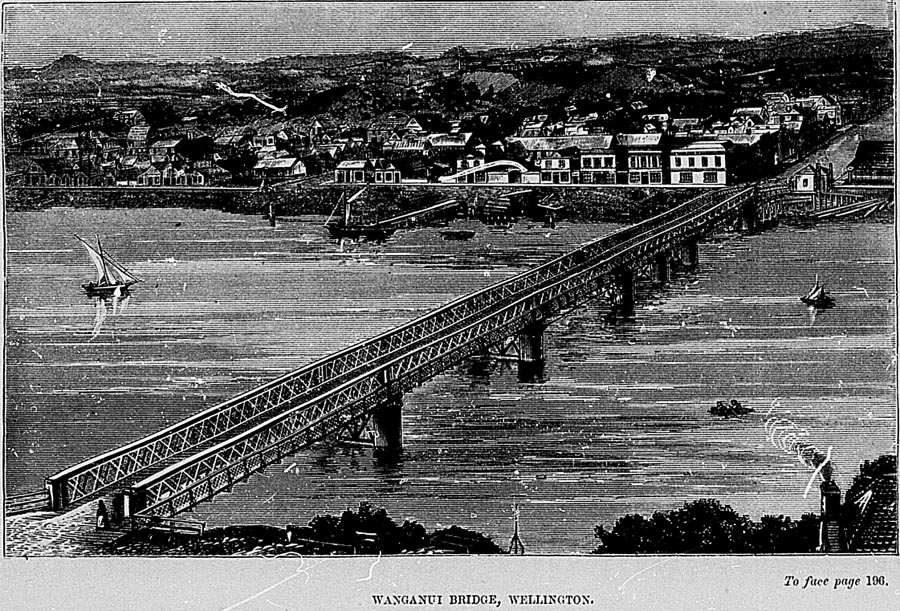

| WANGANUI BRIDGE | 197 |

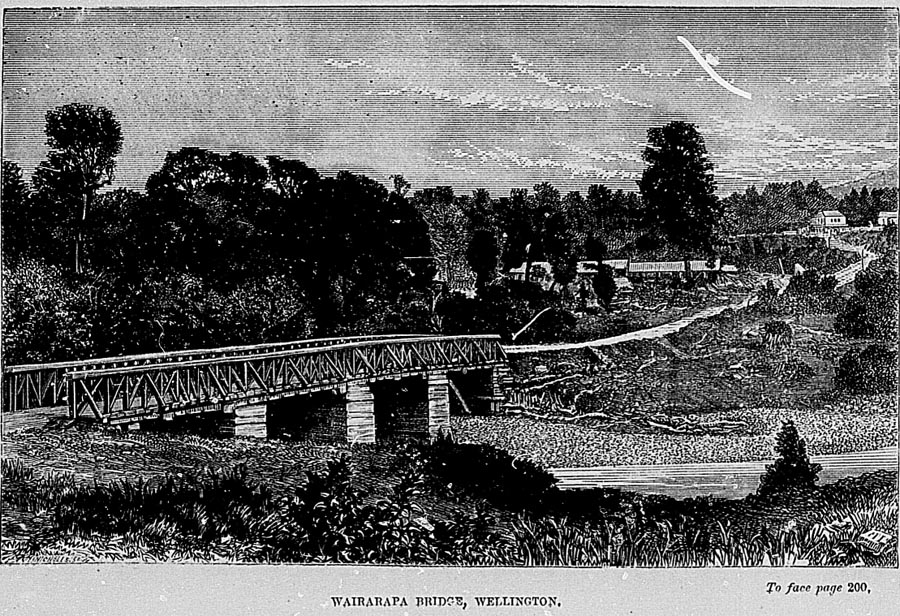

| WAIRARAPA BRIDGE | 201 |

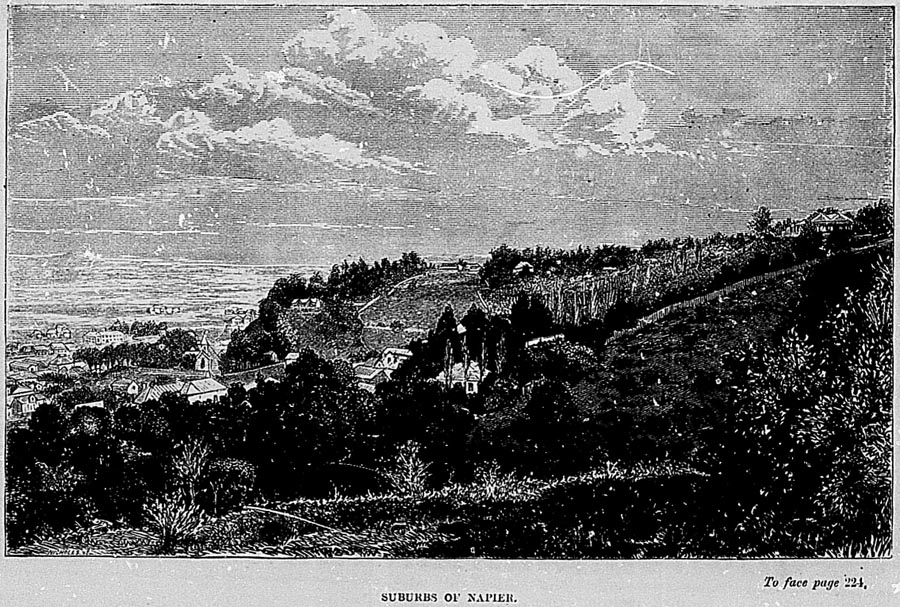

| SUBURBS OF NAPIER | 221 |

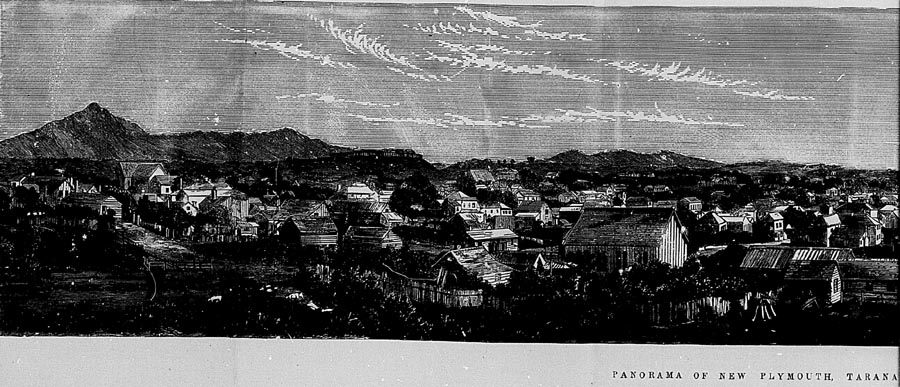

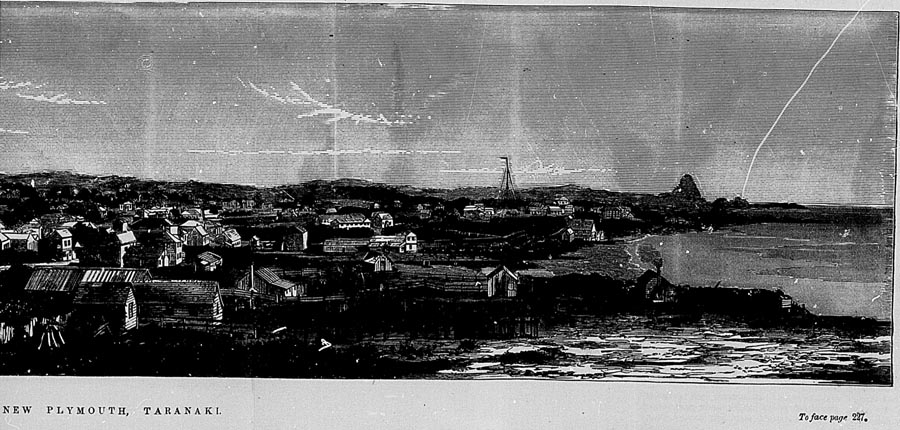

| PANORAMA OF NEW PLYMOUTH | 227 |

| A CREEK | 231 |

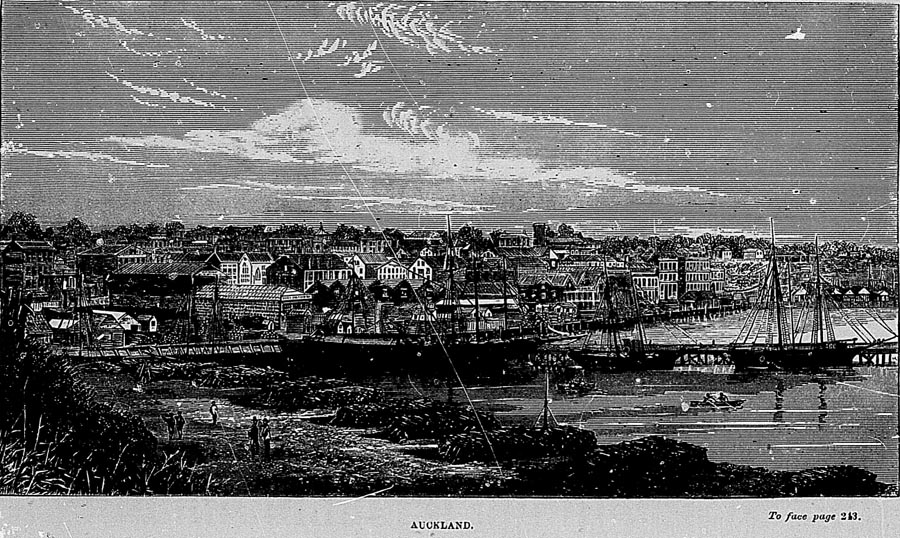

| AUCKLAND | 242 |

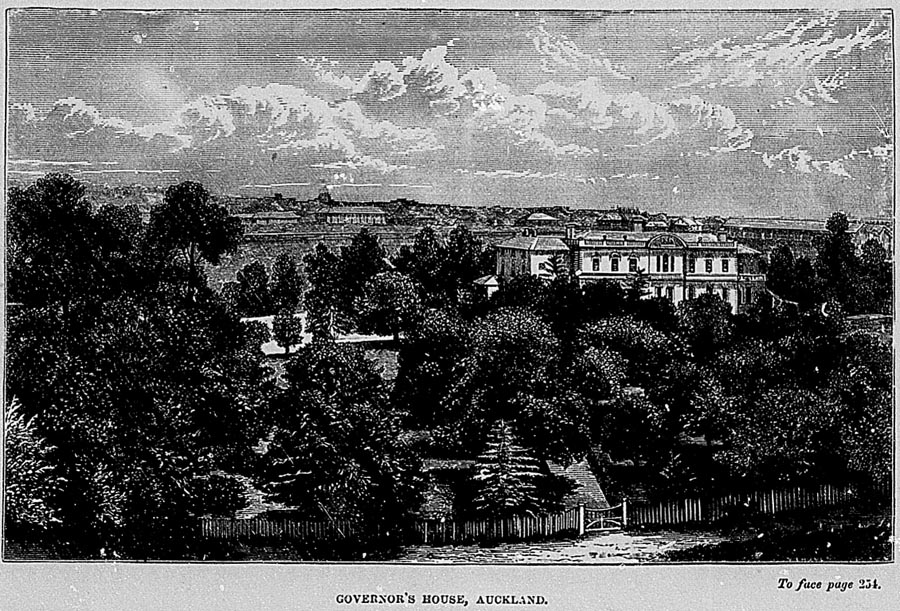

| GOVERNOR'S HOUSE, AUCKLAND | 255 |

IN order that this Handbook may be fairly estimated, it is necessary to explain the manner of its preparation. Most of the works about New Zealand have been written either by those who have made only a short visit to the Colony, or who, possessing an acquaintance with some particular part or parts of the two Islands, have been still unable, however much inclined, to do justice to the several Provinces into which New Zealand is divided.

The colonization of New Zealand has been conducted by several communities, which, as organized and initiated, were perfectly distinct in their character, their objects, the bonds that held them together, and their plans of operation. As might be expected, the isolation in which these communities dwelt assisted for some time to intensify the distinctness of their characteristics. Of late years, the isolation has yielded to the intercourse consequent upon larger facilities of communication. At first, some of the Provinces occasionally heard news of each other more rapidly from their communications with Australia than from their direct communications. But for many years past steamers have abounded on the coast, and there has been much intercommunication. The consequences are that the Provinces know more of each other; they have in many cases exchanged settlers and residents; and the old exclusiveness has assumed rather a character of ambitious competition for pre-eminence in the race for wealth and material advancement. The railways and roads which are being constructed will much increase the intercommunication between different parts of the Colony, and will tend to further reduce the Provincial jealousy that still survives. But not for a long time to come, if ever, will the characters the settlements received from their early founders be entirely obliterated.

The object of this Handbook is to give to those who may think of making the Colony their home or the theatre of business operations, an idea of New Zealand from a New Zealand point of view. To do this, it was necessary to recognize the distinctions which have been already explained. No one man in New Zealand could faithfully interpret the local views of the various Provinces. It was, therefore, determined that the book should consist of a number of papers, some devoted to the Colony as a whole, but most of them independent accounts of separate localities. In editing these papers, the difficulty arose of deciding whether to permit a certain amount of overlapping of narrative, some little discrepancy in statement of facts, and yet larger difference in elaboration of views, or to so tone down the papers as really to frustrate the purpose which led to their separate preparation. The decision was in favour of preserving the distinctness of the papers, even at the risk of affording grounds for carping criticism. In some of the papers, extravagant exhibitions of local favouritism have been much toned down, but enough has been left to supply clear evidence to the reader that there is hardly a Province in New Zealand, the residents in which do not consider it specially favoured in some respects beyond all the other Provinces. To ignore this feeling—the legitimate and in some respects valuable outcome of the original system of settlement— would be to fail to convey a homely view of New Zealand.

It must be clearly understood that when, directly or by implication, comparisons are instituted between different Provinces, they are the writer's, not the editor's. Not that it should be supposed the Provinces of the Colony are uniform in their conditions. A long line in the ocean, trending nearly north and south, New Zealand, for its area, extends over many degrees of latitude, and possesses much variety of climate. There is also wide variety in natural and physical features, and in resources, whether mineral or agricultural. In "specialities," therefore, there is no doubt much difference in the capabilities of the Provinces, and perhaps, to some extent, it would be well if this were more generally admitted, and efforts were made to develop in each Province its own proper capabilities. Success naturally induces imitation, and hence, perhaps, the existing industries may have become too deeply grooved. The fact that sheep and wheat have been so successful in the South, does not make it a necessary consequence that they are the most suitable productions for the North. Amongst the benefits an influx of population will bestow on the Colony, may be anticipated that of an impetus being given to new industries, suitable to the circumstances of the several parts of the Colony, but which in the early days were overlooked.

Those who incline to make New Zealand their home should not form extravagant anticipations of it. It is not paved with gold, nor is wealth to be gained without industry. Our countrymen of the United Kingdom may form an idea of it if they suppose it to be a very thinly-peopled country, with numerous points in common with the Islands of Great Britain, but possessing, on the whole, a much better climate, free from pauperism, more free from prejudices of class, and, therefore, opening to the industry and ability of those who have not the adventitious aid of family connections to help them, a better road to advancement; a country in which there is a great variety of natural resources, and which, therefore, appeals to persons of much variety of taste; a country which may boast of some of the most magnificent scenery in the world; a country in which the natural wonders of many parts of the globe are congregated. Norway, for example, would not be ashamed of the fiords of the West Coast of the Middle Island: the glaciers there would also respectably contrast with glaciers elsewhere. The hot springs of the Lake district are more marvellous than the geysers of Iceland. It is a country with an immense extent of seaboard compared with its area, with splendid harbours, many, if not extensive, rivers, fine agricultural land, magnificent forests, and lastly, one which, besides possessing in abundance the key to manufacturing wealth — coal — has alluvial and quartz gold deposits, in working which, those whose tastes incline them to mining may always find a livelihood, with the possibility of attaining large wealth by a lucky discovery. Though sparingly populated, it is not denied the benefits which science has opened to modern civilization. The telegraph penetrates its length and breadth, and railways are being constructed throughout it. In course of time, it must carry a population of millions, and every acre of available land must become valuable. Yet with the knowledge that this must be, there is so little capital, not required for industrial uses, that millions of acres of land are open to purchase at prices which, a generation hence, will probably represent their yearly rent. There are not many instances of vast accumulations of wealth in individual hands. It would be as difficult to find a millionaire in New Zealand, as it would be in England to find a labourer enjoying anything approaching the advantages enjoyed by the New Zealand labourer. Money is more widely distributed. The small tradesman, the mechanic, or labourer, in short, any one who is fitted to make New Zealand his home, and who is not incapacitated by ill health, may, with ordinary frugality and industry, and without denying himself a fair share of worldly enjoyment, save money, and become, if his ambition point in that direction, a proprietor of acres.

New Zealand has, apparently, when tested by its population, a heavy public debt; but when tried by the only true test, the burden which the debt bears to the earnings of the people, it compares favourably with older and more settled countries, although the public debt of the Colony includes works, such as railways, water-works, roads, and bridges, which in other countries are either the results of joint-stock enterprise, or of local taxation, or of loans not included in the general indebtedness. Again, in the Colony, against the public debt there is to be placed an immense and valuable estate in the land which still belongs to the Crown. The charge per head upon the population, on account of New Zealand's public debt, taken as a whole, was some months since computed to be £1. 17s. 4d. per annum. That total was thus composed: — On account of Colonial indebtedness, exclusive of Public Works and Provincial, 18s. per head; on account of Public Works, 6s. 8d.; on account of Provincial Loans, 12s. 8d.; making together £1. 17s. 4d. But taking the test of the average earnings of the population, the charge per head on account of New Zealand's total indebtedness, is computed to be 2.4 per cent. on the average earnings, while in the United Kingdom it has been computed at 28, and in the United States, at 2.7 per cent. In the former, the cost of railways, and of other public works which are here regarded as "Colonial," is not included; in the latter, the State debts are included. Exclusive of Provincial indebtedness, the Colonial debt, including that for railways and some other public works, is computed to be equal to an annual charge per head of about 1.6 per cent. on the average earnings of the population. The Provincial indebtedness is secured on the Crown lands, and these, at a moderate estimate, are worth at least four times the amount of the Provincial debts. It is to be remembered that fresh arrivals, from the increased wants they create and work they supply, not only participate in the average of earnings, but on the whole add to the average, whilst they diminish the amount per head of the indebtedness of the country. So that what is going on in New Zealand, and what will continue to go on until the Colony is reasonably peopled, is a tendency to increase the average earnings and to diminish the average burden of the public debt, or if that debt is being added to, the average burden on the profits of the people may still remain unincreased.

Whilst these papers were in course of preparation, the Census was being taken. It has not been found possible to incorporate many of the results with the various statistics throughout the pages of the book; but a separate paper is presented, showing as much of the information obtained from the Census as at the latest moment is procurable. Some interesting revenue returns are also given. It will be observed that the two-great branches of revenue, the Colonial and Provincial, are alike increasing in a remarkable manner.

In the pages of the Handbook, frequent reference is made to the various land laws in force in the Colony. The natural disadvantage of many varieties of land laws is, to some extent, compensated by the larger range of choice of conditions presented to the intending settler. Without giving an epitome of the different systems, it may be observed that the object of them all is to promote settlement, their framers holding, in many cases, distinct views as to the circumstances and conditions most likely to promote that object. It is important to remember this, because from it follows the fact that the tendency of all amendments in the land laws, or modifications in the mode of applying them, is in the direction of making the land more available for settlement. For example, an arrangement has just been made between the General Government and the Provincial Government of Wellington, whereby the latter agrees to four blocks, of not less than 20,000 acres each, being selected out of the best land in the Province, to be surveyed into sections of from 50 to 500 acres each. It is agreed that every other section of these shall be open to the free selection of any purchaser, at prices to be fixed in advance: the purchase-money to be paid in instalments, extending over five years. Under this plan, any industrious person, possessed of good health may become a freeholder. Some of the differences in the land laws arise only partly through opposite opinions as to what is most likely to promote settlement, and are principally to be set down to the different nature of the lands and the circumstances of the Provinces. In Otago, for instance, where the desire is to make the land laws in the highest degree liberal, a new system is being adopted, of deferred payments, with conditions of cultivation. In Canterbury, one simple plan has been adopted from the first. Any one may select from the Crown lands throughout the Province, at the price of £2 an acre, cash, without conditions of cultivation and residence. In Auckland, some extent of land is given away in the shape of free grants of forty acres to persons who fulfil the prescribed conditions of cultivation and residence. Other Provinces have modifications or varieties of these several plans; in all, the desire is to see the land cultivated, and from that desire will probably, sooner or later, arise a nearer approach to uniformity of system. The Assembly last year passed an Act, under the provisions of which every person approved by the Agent-General, who pays his own passage to the Colony, may claim a free grant of land to the value of £20 for himself and for any adult member of his family, whose passage is also paid. Two children are reckoned as an adult. The Crown grant of the land is to be conditional on occupation and use, but the immigrant is to be allowed to remain five years in the Colony before selecting his land, and he may select it in any part of the Colony where land is open for sale.

Let it not be thought that for all persons New Zealand is a suitable home. It is a land of plenty to the colonist who can do work such as the Colony requires, or who can employ others to do such work for him. But it is no suitable home for those who cannot work or cannot employ workers. The mere ability to read and write is no sufficient justification for a voyage to New Zealand. Above all, let those be warned to stay away who think the Colony a suitable place to repent of evil habits. The ne'er-do-well had better continue to sponge on his relations in Great Britain, than to hope he will find sympathy for his failings and weaknesses in a land of strangers: strangers, moreover, who are quite sufficiently impressed with the active and hard realities of life, and who, being the architects of their own fortunes, have no sympathy to throw away on those who are deficient in self-reliance. This warning is not altogether uncalled for. It is astonishing how many people are sent to the colonies to relieve their friends of their presence, no heed, apparently, being given to the fact that these countries are not at all deficient in temptations to evil habits, and that those who are inclined to such habits had much better stay away. An instance not long since came under the writer's notice. A wealthy settler received a letter from an English gentleman of whom he had not before heard. The writer explained that his acquaintance with a mutual friend induced him to write and to introduce his son, the bearer, who was visiting New Zealand for the purpose of settling there. He was sorry to say his son had not been successful at home in anything he had tried. He had had to give up the army, and was so very weak and easily persuaded, that it was hopeless to put him to anything in England. The writer would, he said, be content if the gentleman he was writing to would give his son a home and £100 a year till he could do something better. The young gentleman who presented this letter at once intimated that a loan of £10 would be acceptable. He received it. The day was Saturday: on the Monday following, he called again for a further loan—the first £10 was gone. He was naturally denied, and the next intelligence of the young hopeful our settler received, was an order for the payment of a considerable debt. Such prodigals are not suited to the Colony. It would be better to kill the fatted calf on their account, without any intervening absence. Young women of good character, and who are not disinclined to domestic service, need not hesitate to venture to New Zealand. The demand for servants is such that employers are only too glad to obtain respectable young women, and to teach them in part their duties. That demand—for the information of the unmarried daughters of Great Britain, we may observe—is occasioned by the difficulty that exists in keeping servants for any length of time, on account of the readiness with which they are able to get married. The single young man who comes to New Zealand is not long in finding the means to comfortably furnish a house; and, naturally, he thinks that she who shows herself well versed in discharging domestic duties, will be able to make his home a happy one. A short courtship, a brief notice to her employer, and another home is set up in New Zealand; another notice appears in the local papers, "Wanted, a nurse," or housemaid, cook, or general servant, as the case may be. This is all very homely; but the romance of the Colonies is of a very domestic nature—"to make homes" is another mode of expressing "to colonize."

It would not be doing justice to New Zealand to avoid mentioning one other circumstance, though to do so might lead to the appearance of a desire to praise the Colony. All, however, who have a knowledge of New Zealand will corroborate the statement that this Colony gains a singular hold upon those who for any time have resided in it. There are very many persons who have realized a competency, who have nothing to bind them to the Colony, and who yet prefer remaining in New Zealand to living elsewhere. The pleasures and advantages the Old World offers, appear to weigh as nothing with them, when compared with the enjoyments and freedom of life in New Zealand. The climate and the scenery, together with the intimacies which rapidly spring up in colonial life, are no doubt the reasons for this strong liking. For health-restoring properties, the climate of New Zealand is wonderful. There are numbers of persons enjoying good health in the Colony who years ago left England supposed to be hopelessly afflicted with lung disease, their only hope—that in New Zealand the end might be a little longer deferred. This is not written in selfishness, for it is by no means desired to make New Zealand a sanitarium. But this Handbook is not prepared with a view to its consequences. The design, as has been said, is to give a New Zealand view of New Zealand; and it is hoped that, in its pages, the merits and demerits of the Colony will alike be apparent. The order in which the Provinces are dealt with is from south to north, and quite independent of their relative size and importance.

The Editor expresses his acknowledgments for the assistance he has received, in revising the papers, from Mr. E. Fox.

Wellington, New Zealand, May, 1874.

Table of Contents

NEW ZEALAND appears to have been discovered and first peopled by the Maori race, a remnant of which still inhabits parts of the Islands. At what time the discovery was made, or from what place the discoverers came, are matters which are lost in the obscurity which envelopes the history of a people without letters. Little more can now be gathered from their traditions than that they were immigrants, not indigenous; and that when they came, there were probably no other inhabitants of the country. Similarity of language indicates a northern origin, probably Malay, and proves that they advanced to New Zealand through various groups of the Pacific Islands, in which they left deposits of the same race, who to this day speak the same, or nearly the same, tongue. When Cook first visited New Zealand, he availed himself of the assistance of a native from Tahiti, whose language proved to be almost identical with that of the New Zealanders, and through the medium of whose interpretation a large amount of information respecting the country and its inhabitants was obtained, which could not have been had without it.

The first European who made the existence of New Zealand known to the civilized world, and who gave it the name it bears, was Tasman, the Dutch navigator, who visited it in 1642. Claims to earlier discovery by other European explorers have been raised, but they are unsupported by any sufficient evidence. Tasman did not land on any part of the islands, but, having had a boat's crew cut off by the natives in the bay now known as Massacre Bay, he contented himself by sailing along the western coast of the North Island, and quitted its shores without taking possession of the country in the name of the Government he served; a formality which, according to the law of nations (which regards the occupation of savages as a thing of small account), would have entitled the Dutch to call New Zealand theirs—at least so far as to exclude other civilized nations from colonizing it, and conferring on themselves the right to do so. From the date of Tasman's flying visit to 1769, no stranger is known to have visited the islands. In the latter year Captain Cook reached them, in the course of the first of those voyages of great enterprise which have made his name illustrious.

Cook was a self-made man. He began life as an apprentice on board a Whit by collier engaged in the coasting and Baltic trades—the roughest experience that could be had of the business of the sea, but an excellent school to make a practical seaman. But to be a mere practical seaman did not content Cook. After becoming a mate in the merchant service, he entered the Royal navy, and by strenuous perseverance and diligent use of leisure hours, he became an excellent mathematician and astronomer, and a skilful nautical surveyor. He had some experience of war in fighting against the French in Canada, and he executed some useful surveys on the coasts and rivers of that, country; and when it was determined by King George III. to prosecute new voyages of discovery into the little-explored southern seas, Cook's ability was recognized, and, with the rank of lieutenant in the navy conferred upon him, he was appointed to conduct the expedition.

The first of Cook's voyages of discovery began in August, 1768, when he was sent to Tahiti to observe the transit of Venus, an astronomical event of great importance, which required considerable skill and knowledge to note in an intelligent manner. Having performed this duty, his instructions directed him to visit. New Zealand, of which nothing more was known than the little that Tasman had told: After a run of eighty-six days from Tahiti, having touched at some other places, he sighted the coast of New Zealand on the 6th of October, 1769. On the 8th he landed in Poverty Bay, on the east coast of the North Island. It is interesting to those now in the colony, or intending to go there, to know what appearance it presented at the time of Cook's arrival. The aspect of most countries from the sea is less prepossessing than their internal features, and this holds good of the greater part of the east coast of both islands of New Zealand. Portions of the west coast of both, however, present views, from the deck of a ship, unsurpassed in any part of the world. For instance, the hundred miles of Southern Alps, whose snowy peaks pierce the sky at a height of nearly 14,000 feet, their sides clothed with dense evergreen forests, in the very bosom of which lie gigantic glaciers, and their base chafed by the resounding surf of the Pacific Ocean. Then there is the stately cone of Mount Egmont, rising near 10,000 feet, in solitary grandeur, from an undulating wooded plateau almost on the margin of the sea. There are also the stupendous precipices of Milford Sound shooting up sheer many hundreds of feet from an almost fathomless depth of ocean, frowned down upon by the snowy summits of the great Alpine range, while cascades of nearly 1,000 feet fall headlong down their sides. These great features remain to this day as they were at the period of Cook's arrival. Nor has the general character of the country, as a whole, been much changed, in its principal features by the progress of colonization. More of it, no doubt, was then in a state of nature; but much of it is so still. Dense forests, exhibiting new and beautiful forms of vegetation, including the gigantic scarlet flowering myrtle (one of the largest forest trees), the graceful tree-fern, and the bright eastern-like Nikau palm, clothed the mountain slopes and much of the undulating lower country. Elsewhere, vast plains of brown fern, or coarse yellow and hay-coloured grasses, or big swamps bearing the farinaceous raupo and the native flax of the country, the well-known Phormium of commerce. Then there was the feature with which the voyagers, from their long visits to Queen Charlotte's Sound, would be so familiar,—the little retiring cove, with its sandy ox pebbly beach, its few acres of level green, backed up by steep hills covered with lofty trees, and an underbrush of velvety shrubs, arranged by the hand of Nature far more tastefully than could have been done by the Loudons or Paxtons of the civilized world. Ship Cove, Cook's favourite rendezvous, was one of these beautiful nooks—a spot where, as he observed, if a man could live without friends, he might make a model home of perfect isolated happiness. To every Englishman, whose colonizing taste has been inspired by his boyish reading of Robinson Crusoe—(and with how many is not this the case ?)—these charming little bays seem to realize the exact idea of his imagination; and if he could be content to live as Robinson lived, with his little flock of goats, his parrot, and his faithful dog, "the world forgetting, by the world forgot," these are the spots where he would be provided with the surroundings necessary to carry out the idea, and give him all that his fancy could paint or his heart could wish. While there are large tracts of country in New Zealand which present no pleasant feature except to the calculating mind of the sheep-farmer or the agriculturist, there are others, and they are neither few nor far between, such as those to which we have alluded, which combine all the grandeur and beauty that can delight the eye of the most fastidious lover of nature, the painter, or the poet. And much of this must have lain under Cook's eye during his visits to the country.

The spot where Cook landed, however though by no means repulsive, was not one of the most inviting portions of this country to look at. Hills of no great height or grandeur, backing a moderate-sized flat at the head of a bay, whose horns were two not very commanding white cliffs, did not afford a prospect either very imposing or very inviting. At the present time it is the site of a very prosperous and flourishing European settlement; but at the time of Cook's visit it was all barren and unoccupied, except by a few Natives of unfriendly character. No fields of waving corn, no cattle luxuriating on meadows of the now celebrated Poverty Bay rye-grass, drowsily chewing the cud, or waiting with distended udders for the milking-pail.; no hamlet, no church spire, no cottages with children running in and out, no sign of civilization, material plenty, or social life. It must have required an eye of faith to see it as it now is, and to believe that in just one hundred years it would exhibit the picture which now it does.

The circumstances of Cook's first landing were unfortunate. "We landed," he says,

"abreast of the ship, on the east side of the river, which was here about forty yards broad; but seeing some Natives on the west side, with whom I wished to speak, and finding the river not fordable, I ordered the yawl to carry us over, and left the pinnace at the entrance. When we came near the place where the people were assembled, they all ran away; however, we landed, and, leaving some boys to take care of the yawl, we walked up to some huts, which were about 200 or 300 yards from the waterside. When we had got some distance from the boat, four men, armed with long lances, rushed out of the woods, and, running up to attack the boat, would certainly have cut her off if the people in the pinnace had not discovered them, and called to the boys to drop down the stream. The boys instantly obeyed, but being closely pursued, the coxswain of the pinnace, who had charge of the boats, fired a musket over their heads. At this they stopped and looked round them, but in a few minutes renewed the pursuit, brandishing their lances in a threatening manner. The coxswain then fired a second musket over their heads, but of this they took no notice, and, one of them lifting up his spear to dart it at the boat, another piece was fired, which shot him dead. When he fell, the other three stood motionless, as if petrified with astonishment. As soon as they recovered they went back, dragging the dead body, which, however, they soon left that it might not encumber their flight. At the report of the musket we drew together, having straggled to a little distance from each other, and made the best of our way back to the boat, and, crossing the river, we soon saw the Native lying dead on the ground."

The account which the Natives themselves gave of their impressions on Cook's arrival is recorded by Mr. Polack, who had it from the mouths of their children in 1836. "They took the ship at first for a gigantic bird, and were struck with the beauty and size of its wings, as they supposed the sails to be. But on seeing a smaller bird, unfledged, descending into the water, and a number of parti-coloured beings, apparently in human shape, the bird was regarded as a houseful of divinities. Nothing could exceed their astonishment. The sudden death of their chief (it proved to be their great fighting general) was regarded as a thunderbolt of these new gods, and the noise made by the muskets was represented as thunder. To revenge themselves was the dearest wish of the tribe, but how to accomplish it with divinities who could kill them at a distance, was difficult to determine. Many of them observed that they felt themselves ill by being only looked upon by these atuas (gods), and it was therefore agreed that, as the new comers could bewitch with a look, the sooner their society was dismissed, the better for the general welfare."

It is not much to be wondered at that any further intercourse with the Natives at this point should become impossible. Other collisions, attended with similar fatal results, followed on succeeding days, and on the 11th (three days after his first landing), Cook weighed anchor and stood away from "this unfortunate and inhospitable place," as he calls it, and on which he bestowed the name of Poverty Bay. "as it did not afford a single article they wanted, except a little firewood." Had his subsequent experiences been as unpropitious, he would probably not have reported to his countrymen at home so favourably of New Zealand.

There is no doubt that the problem of initiating intercourse with a people of the temper exhibited by the Maoris, and so little civilized as they were, was one difficult of solution. An strangers had never but once before visited the country, and that in the very hasty manner in which Tasman came and departed, and at a place remote from that at which Cook arrived, the Maoris could hardly be expected to appreciate the relations which ought to exist between themselves and their visitors. It must have been a new sensation to most of them, to know that there were such things as strangers; still more, strangers resembling themselves so little and differing of themselves so much. If the inhabitants from the "black country" of Staffordshire, in 1870, exhibited their appreciation of the stranger by "heaving a brick" at him, it is not surprising that the first impulse of the Maoris of Poverty Bay should be to hurl their spears at the "coming man." Cook's idea of meeting such a hostile greeting was, as he tells us, first by the use of firearms to convince the savage of the superior power of the white man, and then to conciliate him by kindness and liberal dealing. Whether any other method were possible, he does not seem to have been allowed by the Natives time to consider; the first collision being, in a manner, forced upon him within five minutes of his arrival, though the challenge was perhaps too hastily accepted.

He soon, however, discovered that the country was not all made up of "Poverty Bays," nor were the Natives, when wooed with a less rough courtship, altogether incapable of access, or entirely obnoxious to strangers. In Tolago Bay, Mercury Bay, Hawke's Bay, the Bay of Plenty, the estuary of the Thames, the harbour of Waitemata, in Whangarei, and at the Bay of Islands, and lastly, at his favourite rendezvous of Queen Charlotte's Sound, he was able to procure the refreshments which Poverty Bay had failed to supply, and he established a footing with the Natives which, if it had in it more of the spirit of barter than of hospitality, was less deterrent than the attitude taken up by those who greeted him on his first arrival, and which ended in the unfortunate events to which we have before referred.

There was no object of greater interest to him than the newly-discovered Maori race, with whose habits and character he was specially instructed to make himself acquainted. He found them savages in the fullest sense of the word. Some writers who have given the reins to their imagination have pictured savage life as a state of Arcadian simplicity, and savage character as a field on which are displayed all the virtues which adorned humanity before civilization brought vice, confusion, and trouble into the world. More truly has it been observed that "the peaceful life and gentle disposition, the freedom from oppression, the exemption from selfishness and from evil passions, and the simplicity of character of savages, have no existence except in the fictions of poets and the fancies of vain speculators, nor can their mode of life be called with propriety the natural state of man." (Whately, Pol. Econ.) "Those who have praised savage life," says Chancellor Harper, of Maryland, "are those who have known nothing of it, or who have become savage themselves." Cook's experience fully verified these views. He found the Maoris almost entirely unacquainted with mechanic arts, their skill limited to the ability to scoop a canoe out of a tree, to weave coarse clothing out of the fibres of the native flax, to fabricate fishing-nets, to make spears, clubs, and other rude weapons of war, or still ruder ornaments for the adornment of their persons, their huts, or their canoes. Beasts of burden they had none, — the women supplied their place. Stone hatchets were the substitute for axes and all cutting tools. The country is full of iron ore, but the use of the metal was entirely unknown. They had no wheeled carriages. Their agriculture was limited to the cultivation, apparently, of two roots—the kumera or sweet potato, and the taro, another esculent plant. Their food consisted of those plants, of eels and sea-fish, rats, occasional dogs, wild fowl, and human flesh; and their nearest approach to bread was the root of the wild edible fern, a not very wholesome or palatable substitute. Cereals they were without. Their religions notions were of a confused order, involving good and evil demons, but without any idea of worship or prayer. Their priests wielded a sort of half moral and half political power in the institution of the taboo, to which they subjected whom they pleased, and the infringement of which involved punishments of the severest sorts. But the one absorbing idea of the race was war. Every tribe and almost every family was at war with every other. Their time was almost wholly spent in planning or awaiting invasions of their neighbours, or in the bloody struggles which resulted; the consequence being, as Cook observes, a habit of personal watchfulness which was never for a moment relaxed. Female infanticide was a common and established practice, which appears to have reduced the proportion of females to males, to something like seven to ten. Female virtue was entirely disregarded before marriage, and not much valued afterwards; while, to crown the whole, cannibalism was the universal practice of the race. Cook had been specially instructed to institute inquiries on this point. There were many persons at home who were sceptical on the existence of cannibalism among any people. The result of his daily observations was to leave no doubt of its existence, and to establish the fact that it was not merely an occasional excess to which those who practised it were impelled by fury and the spirit of revenge against an enemy, but that human flesh was their almost daily and habitual food. A provision-basket was seldom seen without having in it a human head, or other evidence of the fact. It is true that they told him that they ate only their enemies; but so incessant were their invasions of each other, that enemies were never wanting, or if the supply failed, slaves taken in former raids were substitutes at hand, and constantly killed in cold blood for the purpose. Much has been said and written of the deplorable fact that the foot of civilized man treads out the life of the savage; and there are not wanting those who impute to colonization the extinction of the Maori race. A moment's reflection on their habits of life as described by Cook, and still more what we have since learned, must convince any one that their decadence had set in long before his arrival; for it was impossible that any people whose habits of life were such as theirs, and who lived within a circumscribed area, could long continue to exist. We do not believe that the advent of the pakeha has in any degree accelerated the inevitable event, perhaps the reverse has been the case.

Cook did what little was possible towards improving the condition of the New Zealanders. He tried, but failed, to establish the sheep and goat: neither long survived the attempt. He was more successful with the pig, which rapidly increased, till, at the time of arrival of the colonists, nearly the whole Islands were found thickly stocked with wild herds, the descendants of his original importation. He also left the potato behind him, which succeeded well, and to a great extent supplemented the kumera, taro, and fern root. He also planted and gave to the Natives the seeds of other vegetables and garden plants; but though their remains may be seen in the wild cabbage or turnip, and some other degenerated plants, the Natives appear not to have succeeded in their cultivation. He also scattered among them a good many English tools and implements, and some articles of clothing, which, though no doubt soon worn out, gave the Maori a taste for European luxuries and necessaries of life.

We can add little to the picture we have drawn of New Zealand at the time of Cook's arrival. Reference to the accounts of his voyages will supply, in a most graphic and interesting form, the details of the events and observations which space has compelled us to summarize. To those who may wish to know more of the Maori in his primitive state and earliest transition, we recommend Judge Maning's most interesting volume of "Old New Zealand," and his not less graphic description of the war in the North. A volume in the Family Library, published by Knight, entitled "The New Zealanders," contains an authentic and original account, written by a sailor, who was shipwrecked, and lived several years in the country, between the period of Cook's visit and the arrival of missionaries and traders, and will well repay perusal. There are numerous other publications, many of which will give further information.

Cook visited New Zealand several times during his three voyages of discovery, and altogether spent 327 days in the country or circumnavigating its coasts. He quitted it for the last time in February, 1777, just two years before his melancholy death at Hawaii, in the Sandwich Islands. Within a few years afterwards New Zealand began to be occasionally visited by whaling ships; but, with the solitary exception of the shipwrecked sailor whose record is above referred to, no European is known to have resided there before 1814. In that year the Rev. Samuel Marsden, Colonial Chaplain to the Government of New South Wales, visited the lands, and, under his auspices, and on his urgent representations, the Church Missionary Society in England established a mission, the headquarters of which were located at the Bay of Islands. From this time traders from New South Wales began to establish agencies for commercial purposes; and individual Europeans, who were employed by Sydney merchants, or who traded on their own account, became attached to numerous native villages, where they were treated with considerable respect, and regarded as the valuable property of the particular hapu or chief who had had the good luck to secure their residence among them, accompanied by the various advantages which flowed from their presence. Then numerous whaling and lumbering establishments were planted by the Sydney merchants on the coasts of both Islands. These consisted of the very roughest specimens of the sailor class, of runaways from ships, or refugees from the convict prisons of Botany Bay. Alliances were contracted between these men and native women, from which sprang a numerous progeny of half-castes. These whalers and sawyers had many fine characteristics about them: they were brave and hardy, pretty well disciplined in all that concerned their business, and many of them experienced in mechanic arts. Low, exceedingly, as the morale of many of them was, it was yet above that of the savage; and there is no doubt that, to a great extent, their presence tended to bring the native nearer to civilization than he was before. There were, however, spots of deeper darkness than the rest. As the whaling fleet of the Pacific increased, hundreds of ships made Kororarika, in the Bay of Islands, the only town or village then established by Europeans, the place of their periodical refreshment. Their crews, released after a long detention on board ship, plunged into the lowest dissipation, in which the natives became their partners, and the town of Kororarika, which had grown into a considerable place on the strength of the whaling trade, was at times turned into a veritable pandemonium. For proof that this is no exaggeration, we refer to the first of Dr. Lang's letters to Lord Durham (1839), where the reader will find the testimony of an intelligent eye - witness, and facts in detail, but which, bad as it is, scarcely reveals so dark a picture as has been painted to us by other persons who spoke from their own knowledge and observation. Exactly opposite, at Pahia, on the other side of the beautiful bay, in one of its pleasantest coves, with a bright beach of golden sand, washed by the ripple of the sea, stood the mission-station, with its church and printing-office, and there the sacred Scriptures were being translated and printed in the Maori language, as quickly as it could be mastered by the missionaries who had undertaken the work of converting the Maori race. Thus, as everywhere, flowed alongside of each other the tides of good and evil, and the choice between the two was offered to the Maori, as it has been offered to others all the world over, and ever since the world began.

The irregular kind of colonization which was thus going on was attended with innumerable evils, and was beyond all control. It was not possible that the expediency of interference could long escape the attention of the Government of Great Britain, whose subjects were principally engaged in it; nor were the philanthropy and enterprise of the nation less alive to the opening for exertion on their part which the circumstances of the case afforded. So the British Government interfered. First they appointed a "Resident Magistrate," the Rev. Mr. Kendall, one of the missionary body; then a "Resident," Mr. Busby. But these "wooden guns," as the natives called them, were entirely without power, and the effect of their presence very little felt by either Maoris or Europeans. The Colonial Office of the day did foolish things about recognizing the Maori people as an independent nation, and bestowing on them a national flag, thus abandoning the right of occupation resting on Cook's discovery, and rendering it necessary, at a later period, to accomplish a surrender of sovereignty by the natives (though sovereignty was a thing they had never known), in order to prevent the French from taking the possession which the British Government had waived, and turning the country into a colony, or, perhaps, a penal establishment. The action of the Government was also hastened by that of the New Zealand Company, which, wearied out by long negotiations, at last precipitated, without the co-operation or consent of the Government, that systematic colonization which has since peopled the islands with a British population, and of which we shall now give a brief account.

Cook, during his life, had urged on the British Government the colonization of New Zealand, and Benjamin Franklin, the American statesman, had proposed an organization in England for the purpose. But nothing practical was attempted till about 1837, when Lord Durham, as the representative of a number of gentlemen who called themselves the New Zealand Land Company proposed to the Government that they should be incorporated, with powers to colonize the country. The negotiations were at first friendly, and the Government favoured the plan; but ultimately misunderstandings arose, when the New Zealand Company determined to take the matter into its own hands, and despatched its preliminary expedition on the 12th May, 1839, under the command of Colonel William Wakefield, who held instructions to purchase land from the Natives, and to select the site of the first settlement. He arrived in August of the same year, and selected Port Nicholson, in Cook Strait; and on the 22nd January following, the first batch of immigrants arrived. In twelve months they had increased to upwards of 1,200 from Great Britain, besides a few from Australia.

The object of the founders of the New Zealand Company was chiefly to revive systematic colonization, and to conduct on fixed principles operations which had certainly, since the colonization of the British Colonies in America, been left very much to haphazard. South Australia was founded by nearly the same persons, and on the same principles, and almost at the same time; but the colonization of New South Wales and Tasmania, so far as they existed outside of the convict establishments, which were their nucleus, may be said to have been founded without any principle, and the result lift to chance. The founders of New Zealand colonization sought to transplant to its shores, as far as possible, a complete and ready-made section of the society of the old country, with various social orders, its institutions and organizations, maintaining also, as far as circumstances would admit, the relations of the different classes of the population as they had existed at home. Above all things, they believed that the failure of other colonies to become duplicates of the old country, was owing chiefly to the indiscriminate manner in which the waste lands of the Crown had been disposed of, and to the defective proportion which, as a consequence, existed between capital and labour. They determined to remedy this by the adoption of what was known as the Wakefield theory, which consisted mainly in fixing the price of the land so high as to prohibit, for a considerable time at least, its purchase by the labouring man, thus compelling him to work as a labourer till he might be supposed to have compensated the capitalist or the State for the cost of his importation to the colony. The immigration fund was to be supplied by the land sales.

The application of these principles can hardly be said to have been tested at all in the three first founded of the Company's settlements—Wellington, New Plymouth, and Nelson. Its inability to put the colonists, for many years, in quiet possession of the lands it had sold to them, its long and ruinous controversy with the Imperial Government, and the consequent exhaustion of its resources, precluded altogether the experiment receiving a fair trial in the settlements mentioned. In Otago and Canterbury, however, founded at a later date, there were fewer, if any, obstacles, and the remarkable success of those settlements is by many attributed to the principles on which they were founded. The elements of class association (the Free Church of Scotland and the Church of England being respectively taken as the bonds of union), and the high price of land which has been maintained, though with modifications of the original scheme, have no doubt had much to do with the form into which society in those settlements has developed itself, though the unforeseen discovery of gold, and the existence of great pastoral resources, which formed no element in the Wakefield scheme, have perhaps contributed more to the great prosperity of those settlements than any special principle on which they were founded.

Those who are now seeking a home in New Zealand, can scarcely appreciate the feelings of the early colonists, or the trials and difficulties they had to encounter. To descend from the deck of a ship 15,000 miles from home, at the end of a, weary-voyage of from three to five months' duration, on to a shore unprepared for their occupation, without a single house to shelter them, with no friend or fellow-countryman to welcome them, quite uncertain as to the reception they would meet with at the hands of the savage race whose territory they were peacefully but aggressively invading, with few of the conveniences of civilized life, or the appliances for creating them, except so far as they brought them with them in very limited quantities—how different from the experience of those who now arrive in the colony, where, though many external differences present themselves, they find all the machinery of social life, and the general aspect of everything very much as they left them at home. The immigrant who now lands at Lyttelton, Dunedin, Auckland, or Wellington, finds himself surrounded by numbers of his own countrymen, dressed like himself, hurrying about on the various businesses common on the wharfs of any considerable seaport of the old country: he sees shops, with plate-glass windows, and English names above the doors, filled with the latest novelties from London, Birmingham, or even Paris; cabs plying for customers; omnibuses rumbling along the streets; hotels innumerable; churches and schools in moderate numbers; public buildings exhibiting pretentious feats of architectural skill; asphalte pavements and macadamized streets leading out to suburbs thick with comfortable and even handsome mansions, surrounded by well-kept gardens, gay with brilliant flowers and semi-tropical vegetation. Amidst all this he may, perhaps, in any of the towns of the North Island, notice a stray Maori or two, not, however, clad in the dirty blanket or rough flax mat, but "got up" in fashionable European costume, with polished boots, silk hats, gold watch-guards, and probably a silver-mounted riding-whip; and only distinguishable from the other passers-by by the dark skin, and, perhaps, the ineffaceable tattoo. In the early days the settlers felt that they were "colonizing,"—adding a new province to the Empire. Now, the new arrivals "immigrate," entering into the labours of those who went before them. The former was, perhaps, the more "heroic work." The latter is probably the most profitable, and certainly the least laborious. If it is colonizing at all, it is colonizing made easy; and the immigrant may so far congratulate himself that it is so.

Having described the character of the native race, as it was at the period of Cook's arrival, and painted it in the dark colours which truth demanded, it is only fair to say that before systematic colonization commenced it had undergone a great change.

The teaching of the missionaries, if its results were somewhat superficial, had yet penetrated to almost every part of the country. This, and the example of civilized life exhibited in the mission homes scattered over a large area, had done much to qualify the worst features of savage life, and to soften the ferocity of the Maori character. Wars were less frequent, cannibalism nearly extinct. Intercourse with the European trader and whaler, if less elevating, had yet broken down the prejudice against the Pakeha (or stranger), and inoculated the Maori with a taste for European conveniences and luxuries, which could be best gratified by the permanent residence among them of larger numbers of the foreigners. The pigs and potatoes which Cook had left behind had multiplied exceedingly, so that there was an abundant supply of surplus food, without which the new comers would have been but badly off; and the aptitude of the native for trade and barter, and his desire to possess whatever the European had to offer, from muskets to Jews' harps, made him very willing to bring his stores to market. In short, circumstances had, in the' order of Providence, ripened to the point when colonization was possible, which at any earlier period it would probably not have been.

It only remains briefly to mention the order in which the various settlements were formed.

WELLINGTON, as already stated, was founded by the New Zealand Company in 1840. Preliminary expedition for selection of site, August, 1839.

AUCKLAND, established by the first Governor, Captain Hobson, in the same year. It remained the seat of Government till 1865, when, by Act of the Colonial Parliament, and the selection of certain Commissioners appointed at its request by the Australian Governors, Wellington became the capital.

NEW PLYMOUTH, also founded by the New Zealand Company, in September, 1841. Preliminary expedition, August, 1840.

NELSON, founded by the Company in October, 1841.

OTAGO, founded in March, 1848, by a Scotch company working in connection with the New Zealand Company, and by means of its machinery, under the auspices of the Free Church of Scotland, and with an appropriation of a portion of its lands and pecuniary resources to Free Church purposes.

CANTERBURY, similarly founded in December, 1850, in connection with the Church of England.

HAWKE'S BAT was originally a part of Wellington Province, but separated from it, and created a province of itself in 1858.

MARLBOROUGH, originally part of Nelson, separated in the same manner in 1860.

Descriptions of these several settlements, which, under the name of Provinces, now form the political divisions of the colony, with their local history, will be separately dealt with in subsequent chapters of the present volume.

AMONG the numerous races of men with which the Briton has been brought into contact, there is none which has excited more interest than the native race inhabiting New Zealand, and none which has displayed more capacity for adapting itself to the new ways introduced by the Europeans. By nature brave and warlike, and quick to avenge real or fancied insult, the Maori has nevertheless almost altogether discontinued the practices of his forefathers. The intertribal contests of forty years ago are now unknown, and, following the example of their white neighbours, tribes are seen referring to Courts of Law those disputes respecting land which formerly could have been decided only by a conflict. The same readiness of adaptation is shown as to agriculture. From the time of the earliest traditions, the Maori has been a cultivator of the soil. He was well versed in the nature of the lands best fitted for the esculent roots he planted—the kumera or sweet potato, and the taro, or yam. The potato, introduced by Captain Cook, was eagerly adopted and carefully tended. The fruits brought to the knowledge of the Maori by the early missionaries, such as peaches, grapes, apples, plums, melons, and vegetables like the pumpkin, cabbage, bean, &c., were speedily appreciated and propagated; and when, with the influx of Europeans, agricultural implements were imported, he soon rendered himself familiar with them, and the plough with its team of bullocks replaced the old clumsy implements. Whatever may have been the agricultural industry to which the European has devoted himself in New Zealand, he has found native imitators. Maoris keep sheep, and shear them; grow wheat, maize, and other cereals in large quantities; start flour-mills; rear cattle and pigs; and are quite ready to welcome the introduction of any new culture, such as that of the hop or the mulberry. It was qualities of adaptation such as these, and the spread of Christianity among the natives, which drew attention to the Maori race, and which have caused regret for the decrease of their numbers. How rapid that decrease has been, may be judged when it is known that in 1820 the Native population was roughly estimated at 100,000 souls, and that now it amounts to only about 40,000; 37,000 of whom are in the Northern Island; the remaining 3,000 being found in the Middle Island.

When considering the merits and attractions of the colonies or countries to which population is invited, the intending emigrant who inclines favourably to New Zealand is often deterred from giving further thought to this Colony, because of what he is told, or of what he reads on the subject of the Maoris. Their past savage life and customs—their old cannibal habits, and the fiery disposition which kept them for years at warfare with the Europeans, now in one part of the island, now in another—are familiar to the readers of the numerous boo d pamphlets respecting the Colony, such statements have been accepted as proof that all Natives are hostile and that emigration to New Zealand virtually means settling in the midst of a barbarous population, always on the lookout for plunder.

A statement of facts explanatory of the present condition of the Maori race will enable an opinion to be formed as to the correctness or otherwise of the notion that the colonist in New Zealand is exposed to danger from the natives.

It is a fact that the Maori is warlike by nature. Before the appearance of Europeans in the country, intertribal wars were incessant; and after the arrival of Europeans, various causes led to conflicts of more or less importance and duration between the white man and the coloured—conflicts, however, which never became a war of races; for, whenever a body of natives took up arms, there was always found a still larger number who espoused the cause of their new friends, the "pakeha," or stranger.

With regard to the fighting proclivities of the Maoris, and the prominence which has been given to them, there are two remarks to be made. In the first place, the Maori people, as found by the Europeans, were possessed of a certain degree of civilization, the remains, it is thought, of a higher state from which they had degenerated. They recognized the rights of property; they had a code of laws and honour; they had a religion, with a dim idea of a future state; and their minds were gifted with the power of expansion—that is, they could, and did, easily learn. Having no other way in which to employ their intellectual faculties, they devoted them chiefly to one art—that of warfare; and but three occupations found favour with them—war, planting, and fishing. To find a comparison for the stage they had thus reached, and one which is to their credit, we need only look to Great Britain. The Ancient Britons stained or painted their bodies, if they did not tattoo themselves; and they fought lustily amongst each other, until the Romans came and established colonies in their midst. In the second place, the prominence given to the fighting qualities of the Maori arises from his having been brought before the world after the newspaper had become part and parcel of colonization. We have not upon record any sensational telegrams, daily leading articles, or even weekly records of the dangers and difficulties overcome by the early settlers in America; though tradition and local histories inform us of numerous disasters, of wholesale massacres, and of defeats sustained at the hands of the Red Indians, before the white man could firmly plant his foot upon the soil But with New Zealand and the Maori it has been different. The world at large, reading accounts of past troubles and present occasional disputes, and knowing little or nothing of the actual condition of the Maori race, has accepted it as a fact that perpetual strife exists between the colonist and the native.

A simple account of the Maoris in past times is necessary to show the glaring contrast between the man-eating chiefs of two generations ago, and their well-dressed descendants, who not only have votes, but who sit in both branches of the Legislature.

There is not any record as to the origin of the Maori race. Its arrival in New Zealand is, according to tradition, due to an event which, from its physical possibility, and from the concurrent testimony of the various tribes, is probably true in its main facts.

The tradition runs that, generations ago, a large migration took place from an island in the Pacific Ocean, to which the Maoris give the name of Hawaiiki, quarrels amongst the natives having driven from it a chief whose canoe arrived upon the shore of the North Island of New Zealand. Returning to his homo with a flattering description of the country he had discovered, this chief, it is said, set on foot a scheme of emigration, and a fleet of large double canoes started for the new land. The names of most of the canoes are still remembered; and it is related that the immigrants brought with them the kumera, the taro, seeds of the karaka tree, dogs, parrots, the pukeko, or red-billed swamp hen, &c. Strong evidence that there is truth in this reported exodus, is supplied by the facts that each tribe agrees in its account of the doings of the principal "canoes"—that is, of the people who came in them—after their arrival in New Zealand; and that there is also agreement in tracing from each "canoe" the descent of the numerous tribes which have spread over the islands. Calculations, based on the genealogical sticks kept by the tohungas, or priests, have been made, that about twenty generations have passed since this migration, which would indicate the date to be about the beginning of the fifteenth century. The position of Hawaiiki is not known, but there are several islands of a somewhat similar name.

It is believed that the Maoris were originally Malays, who started from Sumatra and its neighbourhood, during the westerly trade winds, in search of islands known to exist to the eastward; and who, after occupying some of those islands, migrated to New Zealand. There is some evidence in support of the alleged Malay origin of the Maoris, or rather there is evidence of descent from a race possessed of higher knowledge than any shown by the Maoris since Europeans first mixed with them. Thus, they now possess the vaguest ideas of astronomy; but in former times they knew how to steer by stars, and old Natives still pretend to be able to point in the direction of Hawaiiki. Again, the recurrence of the seasons for planting and reaping was known by astronomical signs, and each season was ushered in by festivals which were held when certain conjunctions were seen in the heavens. But now there remains only superstition, which promises success or failure to war parties in accordance with the relative positions of the moon and a particular star.

In 1642, Abel Jan Van Tasman, the first European who is known to have sighted New Zealand, found the Natives numerous and fierce; and three of his men were slaughtered at a spot in the province of Nelson, still known as Massacre Bay. During his first voyage in 1769, and on his subsequent visits, Captain Cook learned the warlike character of the Maoris; and in 1772, the French captain, Marion du Fresne, experienced it, he and fifteen of his men being killed at the Bay of Islands, partly in revenge for desecration of places held sacred by the Natives, and partly because a previous visitant, De LunéAville, had put a leading chief in irons.

In 1814, an event occurred which was destined to be of the greatest importance to the natives. In that year, the Rev. Mr. Marsden, from Sydney, New South Wales, landed with some companions at the Bay of Islands, and commenced to preach, to teach, and to study the language. Gradually other missionaries came to then assistance; but, though they toiled hard for years, were generally respected, and made some converts, they were powerless to stop or to check the frightful slaughters which took place as tribe after tribe obtained firearms. The first to acquire them, the Ngapuhi, who inhabit the country to the north of Auckland, overran the greater portion of the Northern Island, slaying and eating those who could offer no resistance to the new weapons. But gradually the supply of muskets and ammunition was increased, tribes became once more on an equal footing, and the same result took place which attended the discovery of gunpowder in Europe—conflicts became rarer, and the slaughter in action was largely diminished.

Soon after 1830, Christianity began to spread, and by 1860 it had acquired a hold over almost the entire native population. Protestant and Roman Catholic clergymen went through the land, and did their best to root out old superstitions, to substitute for them the teachings of the Scriptures, and to promote education. Gradually they brought about a marked change. Churches and schools were built; there was outward observance of religion; old customs fell into disuse; and even when a section of the Maoris rose against the authority of the Government established by the white man, they still retained the faith he had imparted to them.

It was not until 1864, when there was a revival of old superstitions and beliefs, mixed with a creed perverted from the Old Testament, that Christianity among the Maoris received a blow. "Hau-hau" (from one of the most frequent ejaculations in their prayers) was the name given to the new religion. It was accepted as a national one by the tribes then in rebellion, and the influence of the missionaries among them came to an end. But many who eagerly adopted Hau-hauism at first, have since given up it and rebellion at the same time, although some tribes, it is true, still adhere to its doctrines.

But the writer has to deal with the Maori as he is, and with his present condition—not with the past condition of the small section of the race which was in active rebellion a few years ago; nor with the chances and changes of the struggle, carried on at first mainly by Imperial troops under Imperial officers, but brought to a close by colonial forces under colonial officers, after the withdrawal of the British forces.

As a rule, Maoris are middle-sized and well-formed, the average height of the man being 5 ft. 6 in.; the bodies and arms being longer than those of the average Englishmen, but the leg bones being shorter, and the calves largely developed.* The skin is of an olive - brown colour, and the hair generally black; the teeth are good, except among the tribes who live in the sulphurous regions about the Hot Lakes, near the centre of the North Island; but the eyes are bleared, possibly from the amount of smoke to which they are exposed in "whares," or cabins, destitute of chimneys. The voice is pleasant, and, when warlike excitement has not roused him to frenzy, every gesture of the Maori is graceful. Nothing can be more dignified than the bearing of chiefs assembled at a "runanga," or council, and this peculiar composure they preserve when they adopt European habits and customs, always appearing at case, even in the midst of what would seem a most incongruous assembly. In bodily powers, the Englishman has the advantage. Asa carrier of heavy burdens, the native is the superior; but in exercises of strength and endurance, the average Englishman surpasses the average Maori. As to the character of the natives, it must be remembered—if most opposite and contradictory qualities are ascribed to them—that they are in a transition state. Some of the chiefs are, with the exception of colour and language, almost Europeans; others conform, when in towns, to the dress and the customs of white men, but resume native ways, and the blanket as the sole garment, as soon as they return to the "kainga," or native village. The great majority have ideas partly European, partly Maori; while a small section, professing to adhere to old Maori ways, depart from them so far as to buy or to procure articles of European manufacture, whenever they can do so. They are excitable and superstitious, easily worked upon at times by any one who holds the key to their inclinations and who can influence them by appeals to their traditionary legends; while at other times they are obstinate and self-willed, whether for good or for evil. As is usual with races that have not a written language, they possess wonderful memories; and when discussing any subject, they cite or refer to precedent after precedent. They are fond of such discussions; for many a Maori is a natural orator, with an easy flow of words, and a delight in allegories which are often highly poetical. They are brave, yet are liable to groundless panics. They are by turns open-handed and most liberal, and shamelessly mean and stingy. They have no word or phrase equivalent to gratitude, yet they possess the quality. Grief is with them reduced to a ceremony, and tears are produced at will. In their persons they are slovenly or clean according to humour; and they are fond of finery, chiefly of the gaudiest kind. They are indolent or energetic by turns. During planting time, men, women, and children labour energetically; but during the rest of the year they will work or idle as the mood takes them. When they do commence a piece of work, they go through with it well; and in road-making they exhibit a fair amount of engineering skill.

* Doctor Thomson's valuable work has been consulted in preparing this portion of the sketch.

It has been already stated that the Northern Island of New Zealand contains a native population of about 37,000; but it must not be imagined that these are in one district, or that any considerable number are assembled in one place. In fact, they are divided into many tribes, and are scattered over an area of 28,890,000 acres, or 45,156 square miles, giving less than one native to the square mile. The most important tribe is that of Ngapuhi, which inhabits the northern portion of the North Island, within the Province of Auckland. It was among the Ngapuhi that the seeds of Christianity and of civilization were first sown, and among them are found the best evidences of the progress which the Maori can make. Forty years ago, the only town in New Zealand, Kororareka, Bay of Islands, existed within their territories. Their chiefs, assembled in February, 1840, near the "Waitangi," or "weeping water," Falls, were the first to sign the treaty by which the Maoris acknowledged themselves to be subjects of Her Majesty; and although, under the leadership of an ambitious chief, Hone Heke, a portion of them, in 1845, disputed the English supremacy, yet, when subdued by English troops and native allies (their own kinsmen), they adhered implicitly to the pledges they gave, and since then not a shadow of a doubt has been cast on the fidelity of the "Loyal Ngapuhi." Their leading chief died lately. He was a man to whom the Colony owed much, and who may be taken as a type of the Maori gentleman of rank. Tamati Waka Nene (Thomas Walker Nene) was in his youth a distinguished warrior, and assisted in the raids made by his people on the tribes to the southward. Converted to Christianity by the missionaries, he was one of the first chiefs to sign the Treaty of Waitangi, and by his arguments he was instrumental in inducing others to sign, and he remained faithful to the engagements into which he entered that day. His adhered to the Government in every difficulty and trouble which arose, and to the day of his death he was a stanch supporter of English rule, setting to his people an example which they have honourably followed. His funeral was attended by a large number of both races; and, according to his desire, his body was buried in the church cemetery at the Bay of Islands—thus breaking through one of the most honoured of Maori customs, namely, that a chief's remains should be secretly interred in some remote spot, known to but a few trusty followers. During his lifetime he was honoured by special marks of distinction from Her Majesty, and after his death the Government of New Zealand erected a handsome monument to his memory. Since then, the Ngapuhi have given another proof of the good feeling which the New Zealand Government have caused. In 1845, the British forces lost heavily before a "pa," or native fort, called Ohaeawae, then held by a section of Ngapuhi in arms, and the slain were buried near the spot where they fell. Recently, however, the natives, in their desire to prove their friendship, have erected a small memorial church, in the graveyard of which they have with due honour reinterred the exhumed remains of their former foes; thus giving additional evidence of the complete extinguishment of old animosities and jealousies.

A glance at the map will show the progress which is being made with road-works in this part of the Island. Many of the roads are being constructed by native labour, under the management and superintendence of a native gentleman holding a seat in the House of Representatives. In travelling through this district, it is not uncommon to see comfortable weather-board houses adopted by the natives instead of the "whare;" and European dress is found to have to a great extent supplanted the primitive attire of olden days. Indeed, the profits realized by digging kauri gum, and by disposing of produce, stock, &c., with the high prices obtained for labour on public works, or in the kauri pine-forests which constitute the timber wealth of the district, enable the Natives to procure the comforts of dress and of living to which they have now become accustomed. To the north of Auckland, the two races have approached nearer to each other than in any other parts of the Island; and half - castes, a handsome and power-fully-built race, are numerous. The present generation of British settlers has grown up side by side with the Maori youth; and true friendship exists between the settler and the native.