Te Pukapuka Houanga Whaimana o Aotearoa

Statistics New Zealand

In answer to a telephone call, email, visit or letter, Statistics New Zealand information analysts can provide statistical information, or tell you more about the department's other services, including how to access statistics on the INFOS computer database and the Statistics New Zealand website.

Website: www.stats.govt.nz

Telephone: 0508-525-525 (toll free)

Email: info@stats.govt.nz

AUCKLAND

70 Symonds Street

Private Bag

92003

Telephone: (09) 920–9100

Facsimile: (09) 920–9198

WELLINGTON

Statistics House

The

Boulevard

Harbour Quays

PO

Box 2922

Telephone: (04) 931–4600

Facsimile: (04) 931–4610

CHRISTCHURCH

Dollan House

401 Madras

Street

Private Bag 4741

Telephone: (03) 964–8700

Facsimile: (03)

964–8964

Acknowledgements

The New Zealand Official Yearbook 2006 was produced by the Product Development and Publishing Business Unit of Statistics New Zealand, with the assistance of the many individuals and organisations listed in the ‘Contributors’ section at the end of each chapter, or below the sidebars. The department thanks them and the following:

Statistics New Zealand

Business Unit Manager: Gareth McGuinness

Publishing Manager: Lesley Hooper

Project Editor: Paul Cavanagh

Editor: Brendan Hutching

Production Editor: Marie Smith

Illustrations Editor and Photographer: Margaret Low

Technical support: Nicky McCreanor, Shirley Dixon

Other

Graphics and typesetters: Totem Communications Ltd

Cover: Shelley Watson/Sublime Design

Indexer: Jill Gallop

Liability

Statistics New Zealand has made every effort to obtain, analyse and edit the information and statistics used in the New Zealand Official Yearbook 2006. However, Statistics New Zealand gives no warranty that the information or data supplied contains no errors, and will not be liable for any loss or damage caused by the use, directly or indirectly, of material contained in the Yearbook.

New Zealand Official Yearbook 2006

ISSN 0078-0170

ISBN 978186953-638-1

1-86953-638-X

This book is copyright. Except for the purpose of fair review, no part may be stored or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including recording or storage in any information retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. No reproduction may be made, whether by photocopying or by any other means, unless a licence has been obtained from the publisher or their agent.

Copyright © Statistics New Zealand 2006.

Published in 2006 by David Bateman Ltd, 30 Tarndale Grove, Albany, Auckland, New Zealand.

Printed by PrintLink, Wellington, New Zealand.

Table of Contents

List of Figures

- 1.01. Climate norms

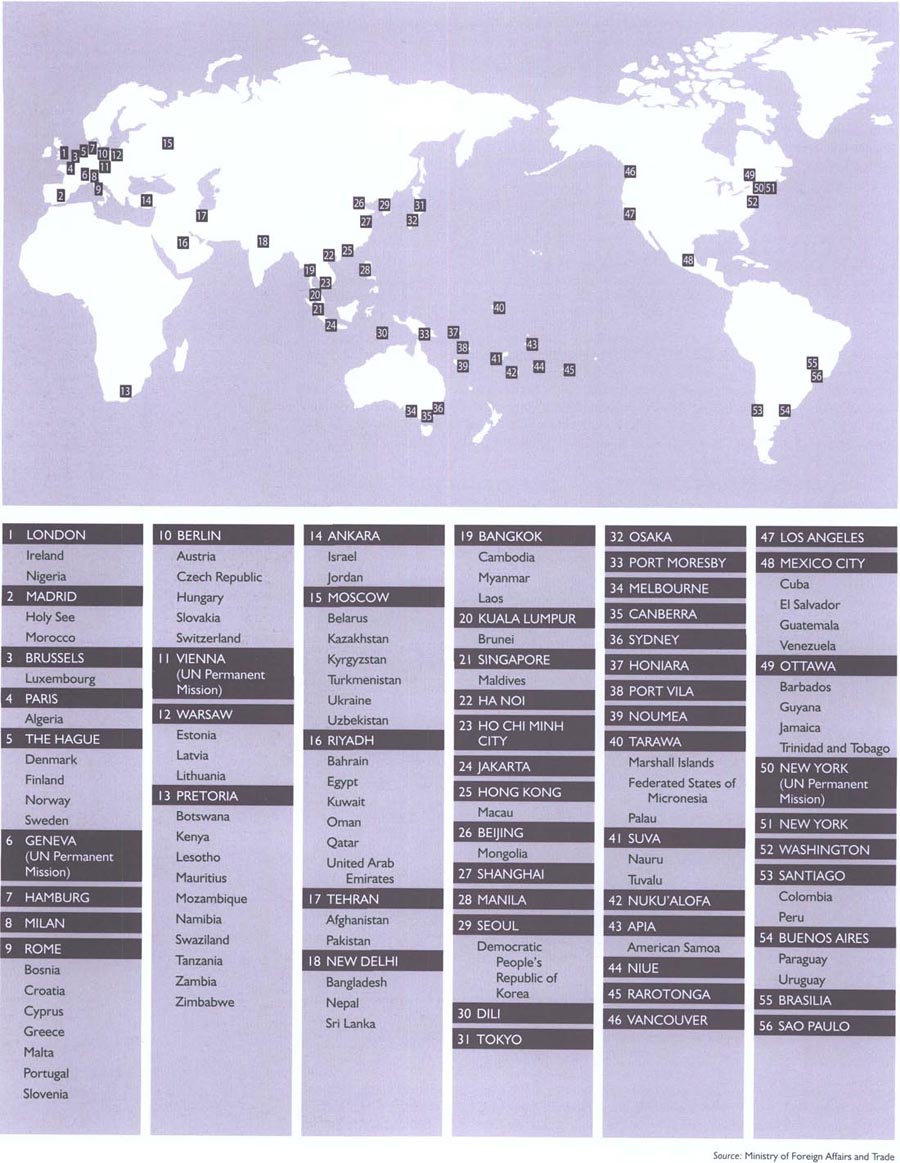

- 4.01. Overseas representation

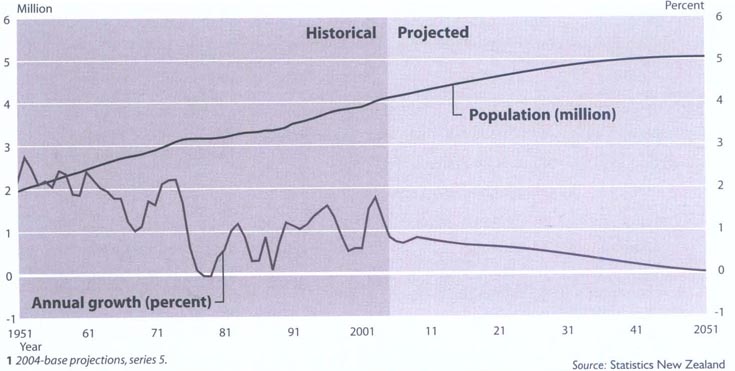

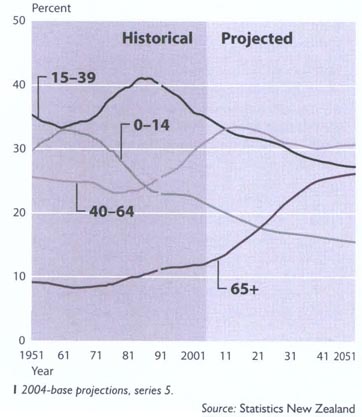

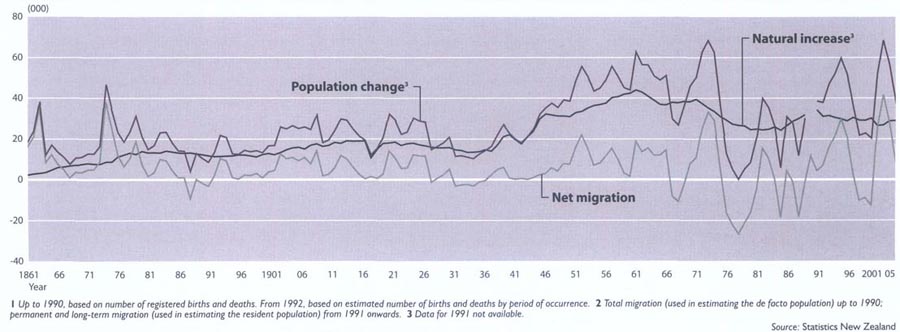

- 5.06. Components of annual population change

Natural increase' and net migration2

Years ending 31 March

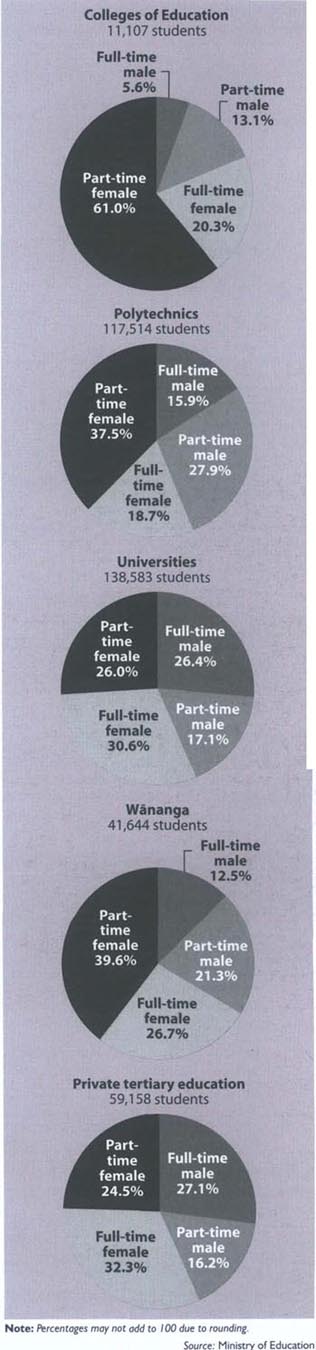

- 9.02. Tertiary attendance 2004

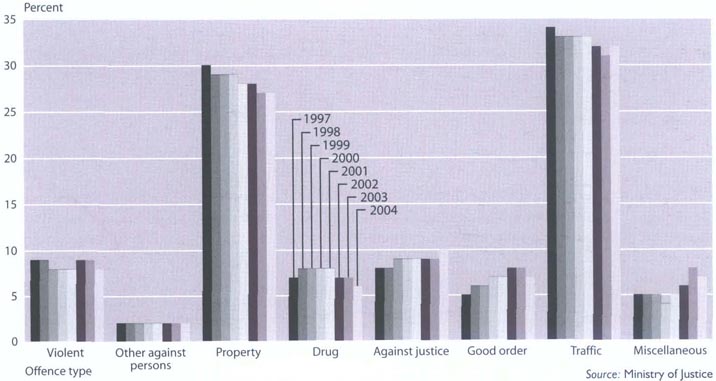

- 10.01. Convictions by offence type

- 16.01. Land use

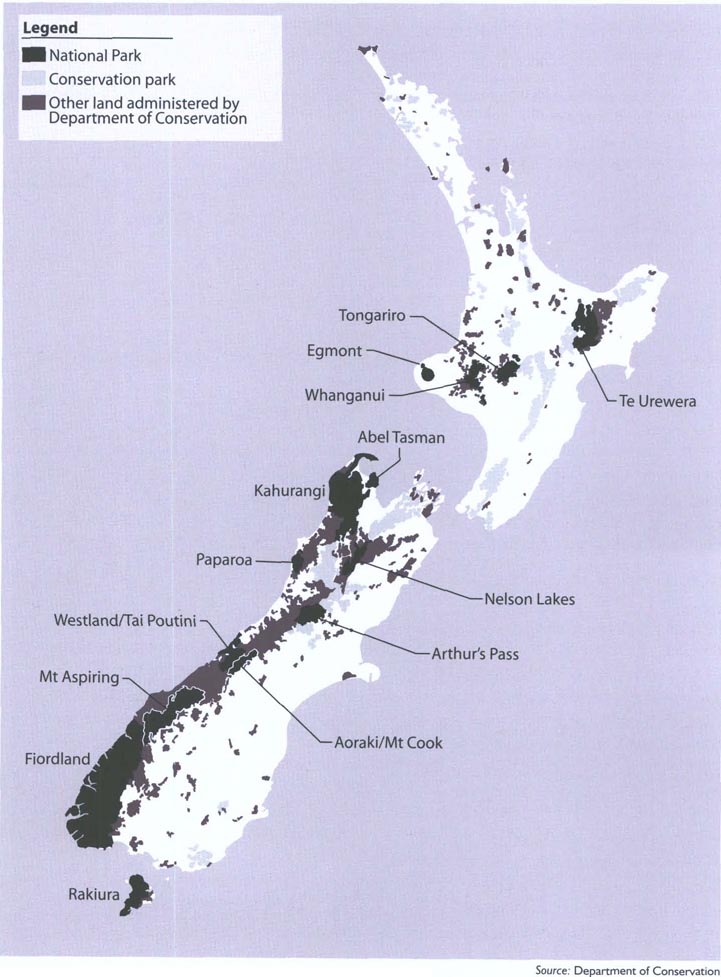

- 16.06. Parks of New Zealand

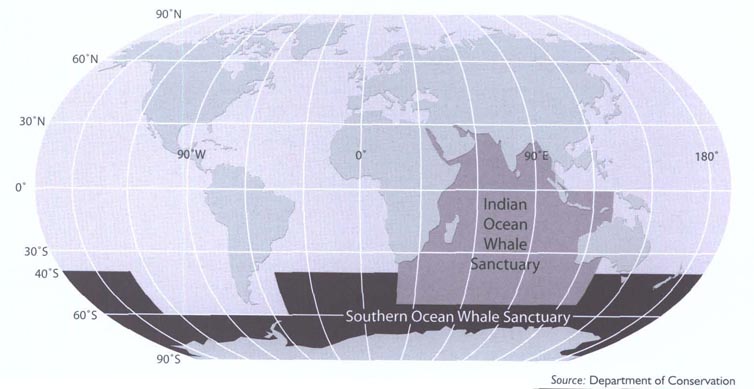

- 16.06. Whale sanctuaries

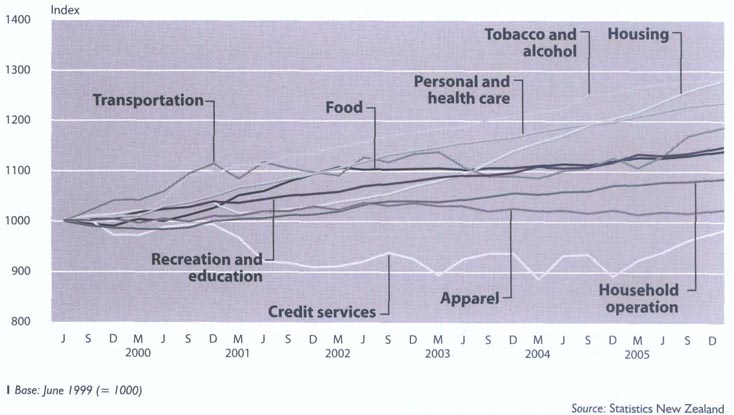

- 17.01. Consumers Price Index groups

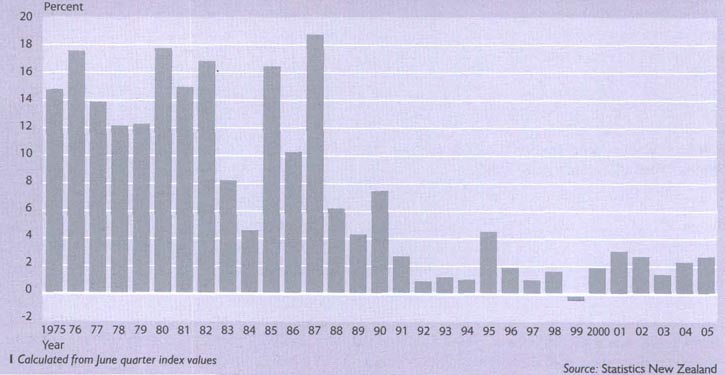

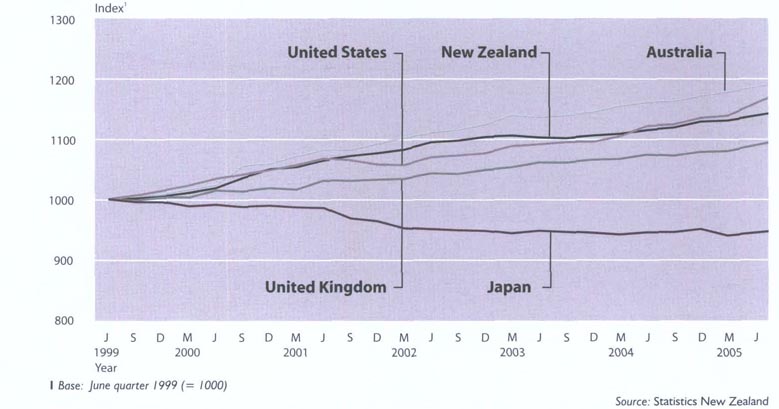

- 17.02. Consumers Price Index international comparisons 1999–2005

Excludes housing and credit services

- 19.02. Land use

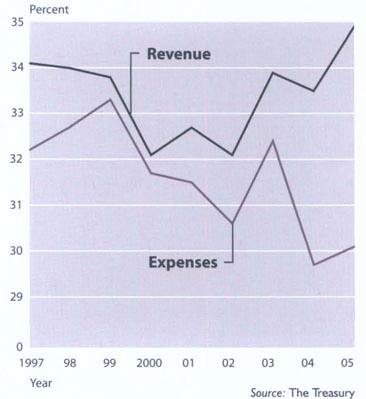

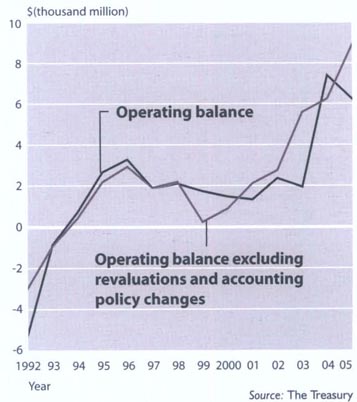

- 27.02. Operating balance

List of Tables

- 1.02. Principal mountains

- 1.03. Principal rivers1

- 1.04. Principal lakes1

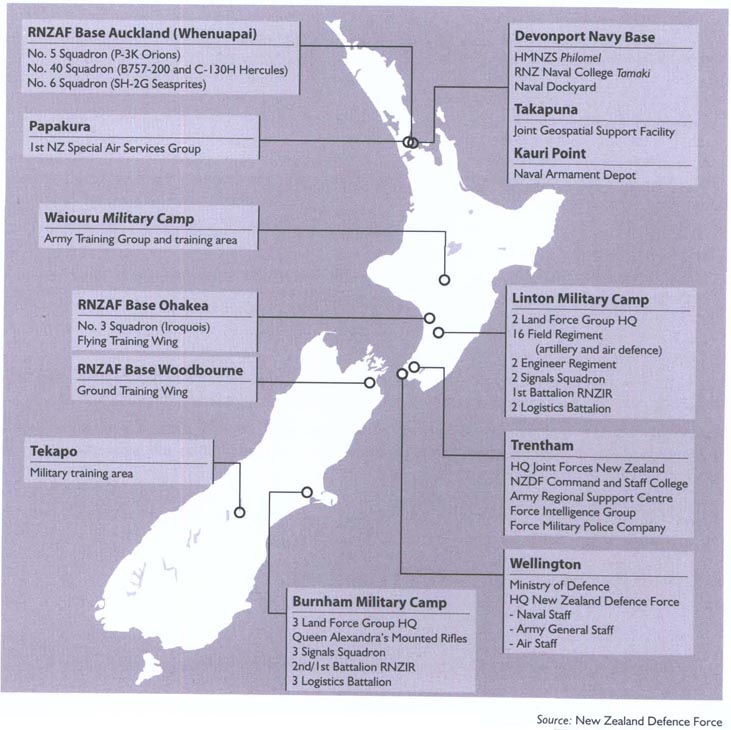

- 4.05. State of the navy

- 4.07. State of the army

- 4.09. State of the air force

- 6.04. Religious affiliation1

- 8.11. Abortion rates

New Zealand and other low fertility countries

Latest available year ending 31 December

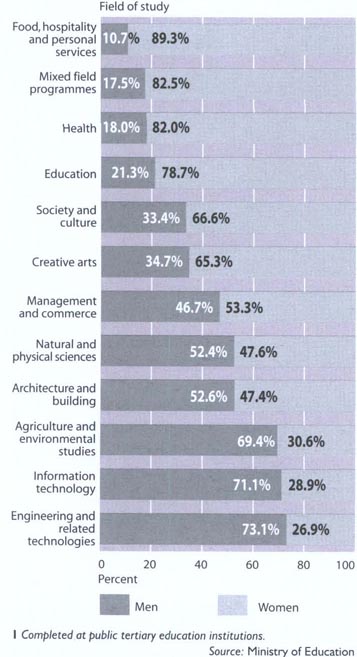

- 9.07. Enrolments at tertiary institutions

By field of study, level of education and sex

At 31 July 2004

- 9.13. Education 1875–2004

- 10.01. Judges of the Supreme Court and Court of Appeal, and judges and associate

judges of the High Court1

- 10.13. Community-based sentences1

- 10.19. Drug seizures (combined NZ Police and NZ Customs Service)By substanceYears ending 31 December

- 11.03. Magazine circulation1

- 11.1. 2004–05 Stamp issues

- 13.01. Gambling statistics

Non-inflation adjusted for year ending 30 June1rounded to the nearest million

- 14.01. Movable public holidays

- 14.05. Labour force participation rates in 20051

By sex and age group

Average for year ending 30 September

- 14.16. Median weekly earnings

Full-time wage and salary/workers

By age and sex

Quarter ending 30 June 2005

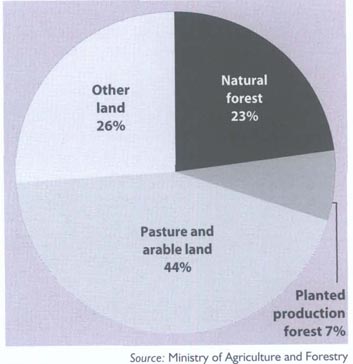

- 16.01. Land use1

- 18.02. Sheep categories

At 30 June

- 18.03. Cattle categories

At 30 June

- 18.05. Average net schedule prices

- 18.14. Pigs

At 30 June

- 21.02. North Island regional employment in manufacturing

By major types of industry, in employee count1

- 21.03. South Island regional employment in manufacturing

2005

By major types of industry, in employee count1

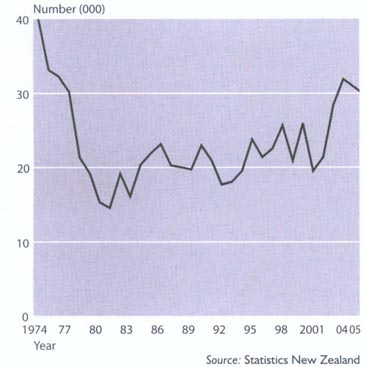

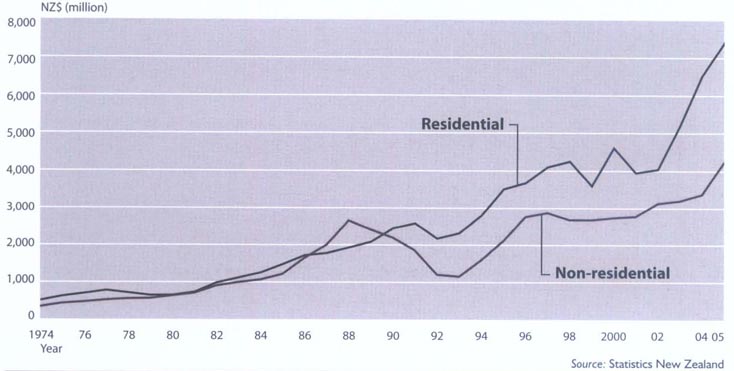

- 22.09. Residential and non-residential building authorisations

By number and value

Years ending 31 March

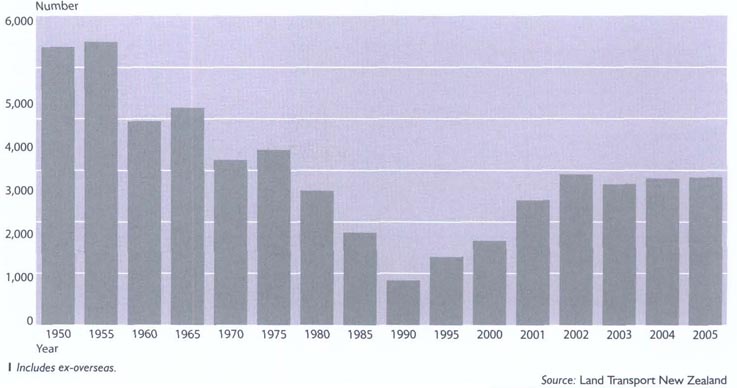

- 23.06. Formed roads and streets

- 24.05. Credit card usage1

By value

- 27.09. Refinancing/repricing risk

Table of Contents

The New Zealand Official Yearbook has provided a comprehensive statistical picture of life in New Zealand for more than 100 years. This 105th edition of the Yearbook celebrates and continues this tradition, providing a wide-ranging picture of New Zealand society in 2006, based on the latest possible information.

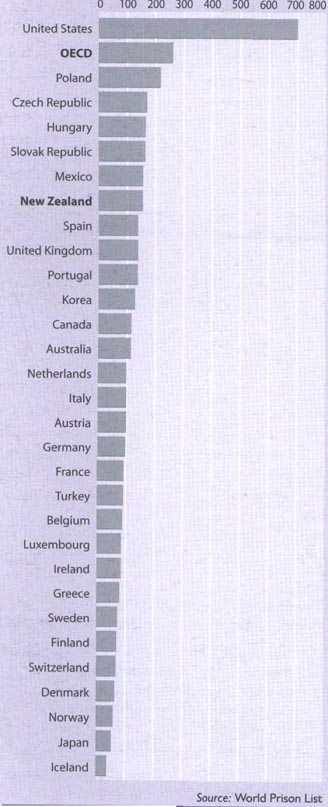

Most recent Yearbooks have carried a theme, and the 2006 edition has an international focus, highlighting New Zealand's position, statistically, on the world stage. Sidebar stories, tables and graphs show ‘How we measure up’ in areas such as population, health and education against the other 29 member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

This international focus is timely. Statistics which are internationally comparable provide a valuable context for evaluation and decision making. New Zealand is an active member of the international statistical community and makes a valuable contribution towards improved global standards and techniques in statistical measures. Internationally, New Zealand's expertise in measuring small populations is used to good effect in its role as a contributor of advice to developing countries, especially around the Pacific Rim. Recent projects have included coordinating the 2004 Census for the newly-formed nation of Timor-Leste and, latterly, the censuses of Niue and Tokelau.

Back home, Statistics New Zealand is taking a leadership role in making government statistics more readily available, promoting the use of statistical standards and managing the burden of government surveys. Data accessibility has been much enhanced by the launch of Statisphere (www.statisphere.govt.nz), an online portal that provides a gateway to government information. Statisphere is a register of all statistics produced by government, and facilitates access to them via links to the relevant ‘producing’ departments’ websites. The portal is a collaborative effort across government agencies and in time will grow to become an essential one-stop shop for those wishing to access government information.

Statistics are primarily about people and their activities, and in this context I would like to pay special tribute to my colleague, the late Kevin Eddy, who died earlier this year. Kevin worked at Statistics New Zealand for more than 30 years and for more than a decade oversaw publication and development of the New Zealand Official Yearbook, making it the accessible and modern publication it is today.

I would also like to offer special thanks to the New Zealand Official Yearbook 2006 team for the high standards they have achieved and to publisher David Bateman Ltd for continuing to provide a high-quality finished product.

On behalf of Statistics New Zealand, I thank the nearly 400 businesses, government departments, nongovernment organisations, academic institutions and individuals for their time, effort and goodwill in providing and updating contributions to the 2006 Yearbook. Their high level of cooperation, not only with the Yearbook but with all our surveys, ensures the continuing high quality of New Zealand's official statistics.

Brian Pink

Government Statistician

The New Zealand flag is the symbol of the realm, government and people of New Zealand. The flag features, on a royal blue background, a Union Jack in the first quarter and four five-pointed red stars of the Southern Cross on the fly. The stars have white borders. The royal blue background is reminiscent of New Zealand's blue sea and clear sky, while the stars of the Southern Cross emphasise New Zealand's location in the South Pacific Ocean. The Union Jack gives recognition to New Zealand's historical foundations and the fact that the country was once a British colony and dominion.

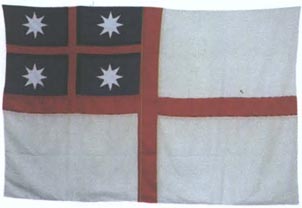

For a detailed history of Te Hakituatahi o Aotearoa, see Chapter 3: Government. The flag features, on a white field, a red St George's Cross. In the upper canton next to the staff, on a blue field, a smaller St George's Cross in red, severed from the blue by a fimbriation of black half the width of the red, and, in the centre of each blue quarter, a white eight-pointed star.

New Zealand has had its own coat of arms since 1911. Before that the United Kingdom coat of arms (featuring a lion and a unicorn on either side of a shield and crown) was used. This design still adorns the top of the pediment on the Old Government Buildings in Lambton Quay, Wellington, which were built in 1875 to house the colony's public service, but which now house Victoria University's law school. One of the few specific changes to flow on from the granting of Dominion status in 1907 was the right for New Zealand to have its own coat of arms. The design was approved by royal warrant on 26 August 1911. The coat of arms was revised in 1956 following further constitutional changes when the country became the ‘Realm of New Zealand’ instead of the ‘Dominion of New Zealand’. Accordingly, the British lion holding aloft the Union Jack was replaced by St Edward's Crown, worn by Queen Elizabeth II at her coronation. At the same time, the dress of the figures at the side of the shield was revamped, some Victorian-looking scroll work at the base of the design was replaced by two ferns, and the motto ‘Onward’ was replaced with ‘New Zealand’.

Table of Contents

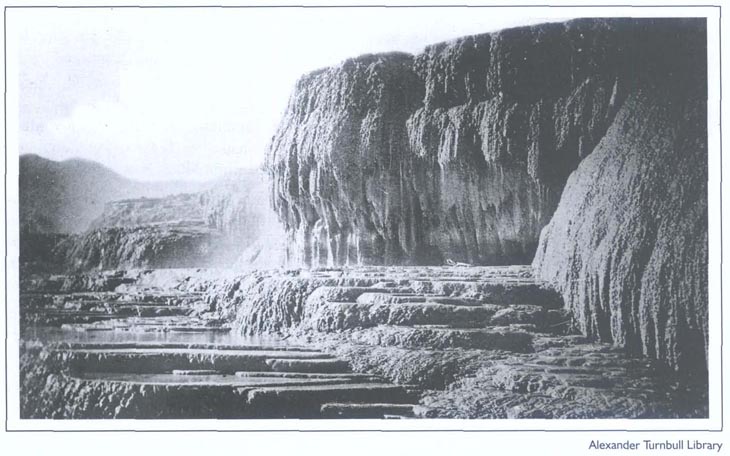

Volcanic eruptions have killed more people than earthquakes in New Zealand in the past 150 years, including the 108 who died in the 1886 eruption of Mt Tarawera (pictured).

New Zealand lies in the south-west Pacific Ocean and comprises two main and a number of smaller islands. Their combined area of 267,707 square kilometres is similar in size to Japan or the British Isles. Table 1.01 gives more detail of the size of the islands.

The main North and South Islands are separated by Cook Strait, which, at its narrowest point, is 20 kilometres wide.

The North and South Islands lie on an axis running from north-east to south-west, except for the low-lying Northland peninsula.

The administrative boundaries of New Zealand extend from 33 degrees to 53 degrees south latitude and from 160 degrees east to 173 degrees west longitude.

In addition to the main and nearby islands, New Zealand also includes the small inhabited outlying islands of the Chathams, 850 kilometres east of Christchurch; Raoul Island, in the Kermadec Group, 930 kilometres north-east of the Bay of Islands; and Campbell Island, 590 kilometres south of Stewart Island.

New Zealand also has jurisdiction over the territories of Tokelau and the Ross Dependency.

Table 1.01. Land area of New Zealand1

| Land area | Size (sq km) |

|---|---|

1Includes all internal waterways (lakes and rivers). 2Includes all offshore Islands 20 square kilometres or larger, except those listed separately. Source: Land Information New Zealand | |

| North Island | 114,154 |

| South Island | 150,416 |

| Stewart Island/Rakiura | 1,681 |

| Chatham Islands | 963 |

| Raoul Island | 34 |

| Campbell Island/Motu Ihupuku | 113 |

| Offshore islands2 | 346 |

New Zealand is more than 1,600 kilometres long and 450 kilometres wide at its widest part, and has a long coastline (more than 18,000 kilometres) for its area. The coast is very indented in places, providing many natural harbours.

The country is also very mountainous, with about three-quarters of the land 200 metres or more above sea level.

In the North Island, the main ranges run generally north-east to south-west, parallel to the coast, from East Cape to Cook Strait, with further ranges and four volcanic peaks to the north-west.

The South Island is much more mountainous than the North Island, with the Southern Alps, a massive mountain chain, running nearly the length of the island. There are many outlying ranges to the Southern Alps in the north and the south-west of the South Island. New Zealand has at least 223 named peaks higher than 2,300 metres. Table 1.02 lists the highest mountains in both the North and South Islands.

Table 1.02. Principal mountains

| Mountain or peak | Elevation (metres) |

|---|---|

1Taranaki or Egmont is the correct format for the dual name as prescribed in the 1986 Gazette. 2The Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences photogrammetrically confirmed the height of Aoraki/Mt Cook as 3,754 metres after a 1991 slip from the peak. Source: Land Information New Zealand | |

| North Island: | |

| Ruapehu | 2,797 |

| Taranaki or Egmont1 | 2.518 |

| Ngauruhoe | 2,287 |

| Tongariro | 1,967 |

| South Island: | |

| Aoraki/Mt Cook2 | 3,754 |

| Tasman | 3,497 |

| Dampier | 3,440 |

| Silberhorn | 3,300 |

| Malte Brun | 3,199 |

| Hicks (St David's Dome) | 3,198 |

| Lendenfeld Peak | 3,194 |

| Graham | 3,184 |

| Torres | 3,160 |

| Sefton | 3,151 |

| Haast | 3,114 |

| Elie de Beaumont | 3,109 |

| La Perouse | 3,078 |

| Douglas Peak | 3,077 |

| Haidinger | 3,070 |

| Minarets | 3,040 |

| Aspiring/Tititea | 3,033 |

| Glacier Peak | 3,002 |

There are 360 glaciers in the Southern Alps. The largest are, on the east, the Tasman (29 kilometres in length), Murchison (13 kilometres), Mueller (13 kilometres), Godley (13 kilometres) and Hooker (11 kilometres), and, on the west, the Fox (15 kilometres) and the Franz Josef (13 kilometres).

New Zealand's rivers (see Table 1.03) are mainly swift and difficult to navigate. They are important as sources of hydro-electric power, and artificial lakes have been created as part of major hydroelectric schemes.

Braided channels of the Rakaia River, Canterbury.

Table 1.03. Principal rivers1

| River | Length km |

|---|---|

1More than 150 kilometres in length from the mouth to the farthest point in the river system, irrespective of name, including estimated courses through lakes. Source: Land Information New Zealand | |

| North Island: | |

| Flowing into the Pacific Ocean – | |

| Rangitaiki | 193 |

| Waihou | 175 |

| Mohaka | 172 |

| Ngaruroro | 154 |

| Flowing into the Tasman Sea – | |

| Waikato | 425 |

| Whanganui | 290 |

| Rangitikei | 241 |

| Manawatu | 182 |

| Whangaehu | 161 |

| Mokau | 158 |

| South Island: | |

| Flowing into Cook Strait – | |

| Wairau | 169 |

| Flowing into the Pacific Ocean – | |

| Clutha/Mata-Au | 322 |

| Taieri | 288 |

| Clarence | 209 |

| Waitaki | 209 |

| Waiau | 169 |

| Waimakariri | 161 |

| Flowing into Foveaux Strait – | |

| Mataura | 240 |

| Waiau | 217 |

| Oreti | 203 |

| Flowing into the Tasman Sea – | |

| Buller | 177 |

New Zealand's artificial lakes created by the South Island's hydroelectric schemes are identified in Table 1.04, which describes the country's principal lakes.

Table 1.04. Principal lakes1

| Maximum depth (metres) | Area (km2) | |

|---|---|---|

1Greater than 20 square kilometres in area. Sources: National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (depths) Land Information New Zealand (areas) | ||

| North Island: | ||

| Taupo (Taupomoana) | 163 | 613 |

| Rotorua | 45 | 81 |

| Wairarapa | 3 | 77 |

| Waikaremoana | 248 | 50 |

| Tarawera | 87 | 41 |

| Rotoiti | 94 | 34 |

| Waikari | 2 | 34 |

| South Island: | ||

| Te Anau | 417 | 344 |

| Wakatipu | 380 | 295 |

| Wanaka | 311 | 201 |

| Ellesmere (Te Waihora) | 2 | 197 |

| Pukaki | 99 | 172 |

| Manapouri | 444 | 139 |

| Hawea | 384 | 152 |

| Tekapo | 120 | 96 |

| Benmore (artificial) | 120 | 75 |

| Hauroko | 462 | 71 |

| Ohau | 129 | 59 |

| Poteriteri | uncharted | 44 |

| Brunner (Moana) | 109 | 41 |

| Coleridge | 200 | 37 |

| Monowai | 161 | 32 |

| Aviemore (artificial) | 62 | 28 |

| Dunstan (artificial) | 70 | 27 |

| Rotoroa | 152 | 24 |

| McKerrow | 121 | 23 |

New Zealand is in an area of the world characterised by active volcanoes and frequent earthquakes. The ‘ring of fire’, as this area is known, forms a belt that surrounds the Pacific Ocean and is the surface expression of a series of boundaries between the plates that make up the earth's crust.

The boundary between the Indo-Australian and the Pacific plates runs through New Zealand, and processes from their collisions have had a profound effect on New Zealand's size, shape and geology.

Renewed mountain building in New Zealand between about six million years ago and the present is primarily responsible for the landscape of today.

Mountain chains have been built by folding and displacement of the earth's crust along faults, or by flexing of crustal plates due to sediment loading and unloading. Due to this activity, well-preserved tilted blocks bounded by fault scarps (steep faces hundreds or even thousands of metres high) are visible in the landscape of some regions.

In the past six million years, waves have eaten back New Zealand headlands and built beaches, spits and bars.

Ongoing movement of the Pacific and Indo-Australian plates is responsible for continued earth strain in New Zealand, and this results in periodic rupture of faults, several of which caused major earthquakes during the past century.

Erosion, enhanced by climate, has transformed the landscape, carving detailed patterns of peaks, ridges, valleys and gorges. Deposition of debris has built up alluvial plains, shingle fans and other construction forms.

At the coast, waves have eaten back headlands and built beaches, spits and bars. Glaciers have carved the sea-filled valleys of Fiordland and have occupied most valleys of the South Island, many of which now have lakes held in by terminal moraines. Sea level changes accompanied formation, and later melting, of global glacial ice. These changes affected the erosion and deposition of rivers and were responsible for the formation of many prominent river terraces.

Volcanic activity during the past few million years has played an important part in shaping the landscape of the central North Island. The largest volcanic outpourings of late geological times were in the region between Tongariro National Park and the Bay of Plenty coast.

The most recognisable volcanoes in New Zealand, all of which are active, include Ruapehu, Tongariro, Ngauruhoe, White Island and Taranaki or Egmont.

Other major volcanoes are less obvious, but have even more dramatic impacts on the landscape. These are the caldera-forming volcanoes that are now occupied by large central North Island lakes. Lakes Taupo, Rotorua and Tarawera can be thought of as upside down volcanoes.

Small volcanic cones, such as One Tree Hill, Mt Eden and Rangitoto, are an important part of the Auckland landscape. These are dormant, but the volcanic field is still regarded as posing a significant hazard.

Living in New Zealand means living with earthquakes. There is an almost continuous belt of earthquake activity around the edge of the Pacific Ocean that affects the geological stability of many countries on the Pacific rim, particularly New Zealand, the west coast of the United States, Chile, Peru, Japan and the Philippines.

New Zealand's level of earthquake activity is similar to that of California, but slightly lower than that of Japan. A shallow magnitude eight earthquake occurs in New Zealand about once a century, a shallow magnitude seven earthquake about once a decade, and a shallow magnitude six earthquake about once a year.

New Zealand has many earthquakes because it straddles the boundary between two of the earth's great tectonic plates – the Pacific plate in the east and the Indo-Australian plate in the west. These two plates are converging obliquely at about 30 millimetres a year in Fiordland, increasing to about 50 millimetres a year at East Cape.

The plates converge in different ways. In the North Island and the northern South Island, the Pacific plate sinks below the Indo-Australian plate. Earthquakes originating within the subducting Pacific plate are less than 60 kilometres deep along the eastern coast and become deeper westward. In Fiordland and the region to the south, the Indo-Australian plate subducts beneath the Pacific plate, so earthquake sources are shallow in the west and deeper in the east under Fiordland.

Between these two subduction zones, the crust of both plates is too buoyant to subduct, so convergence is accommodated by uplift, which has created the Southern Alps, and horizontal movement along the Alpine Fault. This has resulted in parts of Nelson and western Otago, adjacent five million years ago, now being 450 kilometres apart.

Shallow earthquakes are the most numerous and originate within the earth's crust, which has an average thickness of 35 kilometres in New Zealand. Crustal earthquakes are responsible for almost all damage to property and are widely scattered throughout New Zealand.

In the Taupo volcanic zone, from White Island to Ruapehu, swarms of small earthquakes of similar magnitude are common, and are associated with the area's active volcanism. Although the number of such shocks can be alarming, they rarely cause major damage.

An almost continuous belt of earthquake activity around the edges of the Pacific Ocean affects the geological stability of many countries, including New Zealand.

Earthquake risk. The worst disaster in New Zealand that can reasonably be expected within a generation is a 7.5 magnitude earthquake on the segment of the Wellington Fault within the city. It has a 12 percent probability of occurring within the next 30 years and would affect 200,000 residential properties, from Palmerston North to Nelson, as well as roads, bridges and dams, and services such as electricity, water and sewerage. GNS Science runs national and regional earthquake and volcano monitoring networks. A major upgrade of monitoring equipment began in 2001 with the Earthquake Commission providing core funding of $5 million a year over 10 years. Funding was increased in 2005 after a positive review of the success of the project. The project, known as GeoNet (www.geonet.org.nz), is being undertaken by GNS Science on a not-for-profit basis for the national good. GeoNet equipment at sites throughout New Zealand is linked to GNS Science data centres via satellite, cellular and radio networks, permitting more rapid and reliable determinations of the location and magnitude of all significant earthquakes and volcanic activity within the New Zealand region. GeoNet information is made available to civil defence and emergency management authorities and international earthquake centres, but also underpins current and emerging research on geological hazards. New Zealand scientists undertake a large body of research aimed at improving the understanding of, and ways to mitigate, seismic and volcanic risk in New Zealand. Mitigation measures include improved engineering design of buildings and infrastructure, better prepared communities and better regional planning.

The New Zealand region is characterised by both a high density of active volcanoes and a high frequency of eruptions. Volcanic activity in the New Zealand region occurs within the North Island and offshore to the north-east in the Kermadec Islands. In the past 150 years, volcanoes have killed more people than earthquakes, yet the scale and style of historically-recorded volcanic activity is dwarfed by events known to have occurred in the past 2,000 to 5,000 years.

Volcanism. New Zealand volcanism is confined to five areas in the North Island – the Bay of Islands, Whangarei, Auckland, a zone extending from White Island to Ruapehu, and Taranaki or Egmont. The area from White Island to Ruapehu is known as the Taupo Volcanic Zone and is by far the most frequently active. There are three major types of volcano in New Zealand:

Volcanic fields, such as Auckland, where each eruption builds a single small volcano (e.g. Mt Eden), which does not erupt again. The next eruption in the field occurs at a different place, the site of which cannot be predicted until the eruption is imminent.

Cone volcanoes, such as Taranaki or Egmont and Ruapehu, where a succession of small eruptions occurs from roughly the same point on the earth's surface. The products of successive eruptions accumulate close to the vent to form a large cone, which is the volcano itself. The site of future eruptions can generally be predicted.

Caldera volcanoes, such as Taupo and Rotorua. Eruptions at these volcanoes are occasionally so large that the ground surface collapses into the ‘hole’ left behind. For example, Lake Taupo infills a caldera formed in two episodes about 1,800 and 26,000 years ago.

The Taupo Volcanic Zone contains three frequently active cone volcanoes (Ruapehu, Tongariro/ Ngauruhoe and White Island) and two of the most productive caldera volcanoes (Taupo and Okataina) in the world.

Casualties. Deaths due directly or indirectly to volcanism (and associated hydrothermal explosions) represent the biggest single source of fatalities from natural disasters in New Zealand since 1846.

Table 1.05 lists deaths in volcanic areas of New Zealand since 1846. Economic loss due to volcanism, however, has been low compared with that from earthquakes or flooding.

The cost of the 1995 and 1996 eruptions of Ruapehu has been estimated at $130 million.

However, an assessment of the size and style of volcanic eruptions in the geologically recent past, coupled with consideration of the economic development of New Zealand, especially in the central North Island, shows that the record since 1846 represents only a fraction of the type and size of hazard posed by New Zealand volcanism.

Table 1.05. Deaths in volcanic areas since 1846

| Year | Location (eruption) | Cause/hazard | Fatalities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source: GNS Science | |||

| 1846 | Waihi (Lake Taupo) | Debris avalanche/mudflow from thermal area | c60 |

| 1886 | Tarawera Rift | Large volcanic eruption | >108 |

| 1903 | Waimangu (Tarawera) | Hydrothermal explosion | 4 |

| 1910 | Waihi (Lake Taupo) | Debris avalanche/mudflow from thermal area | 1 |

| 1914 | White Island | Debris avalanche from crater wall | 11 |

| 1917 | Waimangu (Tarawera) | Hydrothermal explosion | 2 |

| 1953 | Tangiwai (Ruapehu) | Lahar and flood from crater lake | 151 |

| Total | >337 | ||

Surveillance. All the active volcanoes in New Zealand are monitored as part of the GeoNet project funded by the Earthquake Commission. This provides a near real-time understanding of volcanoes.

Volcanologists use three primary techniques to establish the status of an active volcano:

Monitoring of volcanic earthquakes. This is done using closely-spaced networks of seismometers, designed to detect movement of magma (molten rock) below the surface and allow assessment of the possible onset and timing of eruptive activity. There are five volcano-seismic networks in New Zealand (Auckland, Bay of Plenty-Rotorua, Taranaki, Tongariro and Taupo). The Auckland and Taranaki networks are operated by regional councils.

Monitoring of ground deformation. This is done using precise geodetic surveys. The concept is that if magma is moving upwards before an eruption it will cause the volcano to swell (i.e. the ground surface to rise) and this swelling can be detected. Most of this work is done using continuous GPS installations on the volcanoes. The lakes at Taupo and Tarawera are also used as giant spirit levels to detect height changes.

Monitoring of volcanic gases. Magma at depth in the earth contains gases (carbon dioxide, together with various compounds of sulphur, chlorine and fluorine) dissolved in it. As the magma rises to shallow levels before an eruption, these gases are released and come to the surface via fumaroles. The temperatures and the abundance of the gases and their relative proportions give information on the state of the magma and how close to the surface it is.

In a volcanic crisis, practical steps can be taken to mitigate risk and lessen the threat to life, but this requires accurate recognition of the onset of a crisis.

This recognition in turn depends on a knowledge of the ‘background’ or ‘normal’ levels of seismicity, ground movement and gas flux at the volcano, coupled with ‘real-time’ determination of any significant changes from this background.

The GeoNet active volcano surveillance programme helps define these background levels.

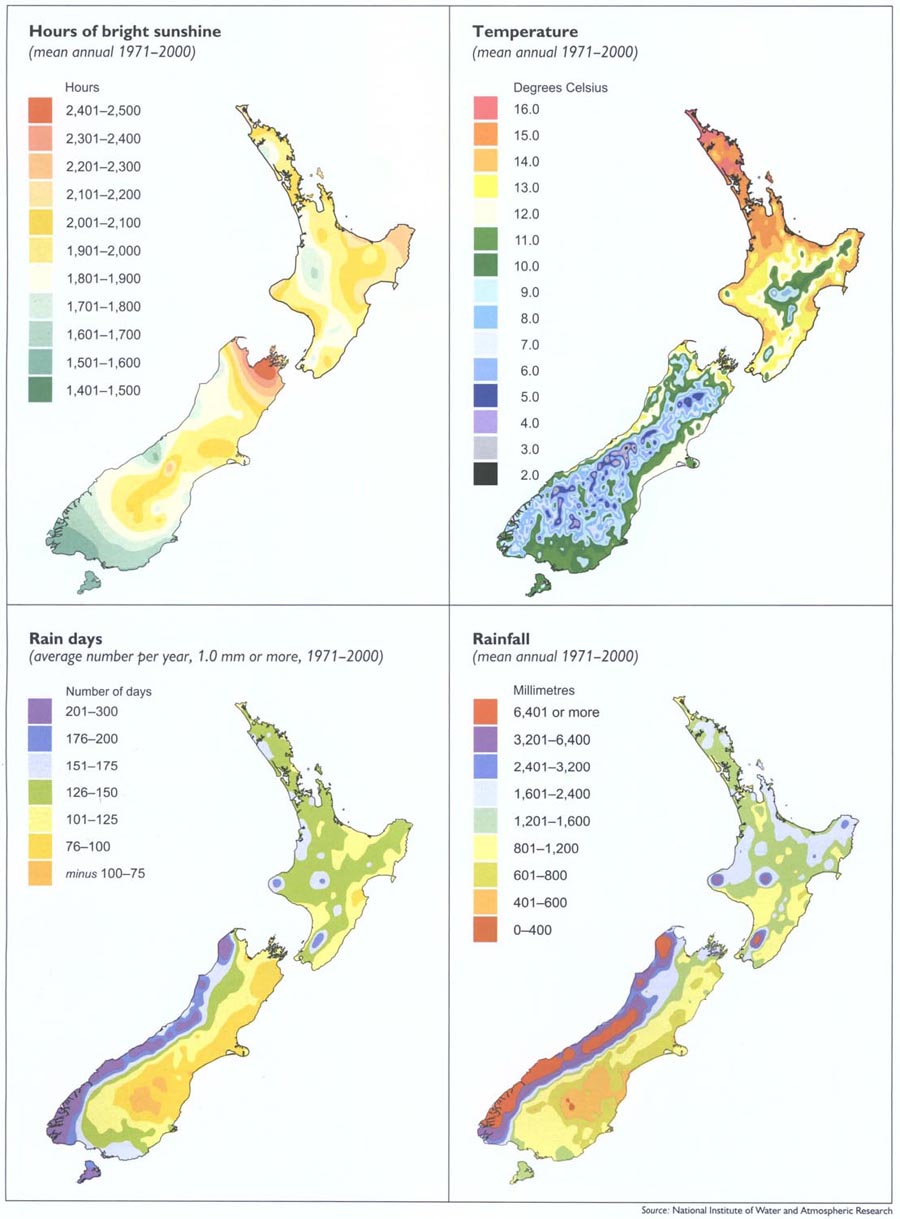

Summaries of New Zealand's climate extremes compiled by the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA) contain detailed descriptions of the most extreme weather events recorded in the country.

Figure 1.01 shows mean annual sunshine, temperature, rain days and rainfall for various parts of New Zealand. The maps are prepared by NIWA and show mean annual figures struck over a 30-year period to create what are referred to as ‘climate norms.’

The next ‘normal’ period for calculating mean annual figures will be 1981 to 2010.

The climate of New Zealand is largely influenced by:

Its location in a latitude zone where the prevailing wind flow is westerly.

Its surrounding ocean environment.

Its mountains, especially the main mountain chain, which modify weather systems as they pass eastwards, and which also provide a sheltering effect on the leeward side.

Day-to-day weather is mostly determined by a series of anticyclones and troughs of low pressure in the westerlies. Consequently, New Zealand's weather is changeable, typically with short periods of settled or unsettled weather. At times, the westerly regime breaks down and there are cold, southerly outbreaks, with snow in winter and sometimes spring; or northerly intrusions of warm, moist air when tropical depressions move southwards into New Zealand latitudes in the summer. The main mountain chain is a major barrier to weather systems approaching from the west. Consequently, there is a marked contrast between the climates of regions west and east of the mountains. This contrast is much greater than north-south climatic differences. Surrounding oceans have a moderating effect on temperatures in most northern and western regions. However, inland and eastern areas can experience large temperature variations.

High temperatures usually occur in the east in warm, north-westerly wind conditions. These high temperatures are often followed by sudden falls in temperature, as cold fronts move up the east coast of both islands. Many parts of New Zealand are subject to extremes of wind, occasionally causing damage to buildings and forests, and rain as depressions with their fronts pass close to or over the country. The rugged terrain is an important factor in enhancement of wind strength and/or rainfall.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) concluded in 2001 that there was comprehensive evidence of climate change caused by human activities during the 20th century. The IPCC report predicted increases in global mean temperatures from 1990 to 2100 of between 1.4 and 5.8 degrees Celsius and global mean sea level increases of between 9 and 88 centimetres.

The report said changes could also be expected in some extreme weather and climate events, including higher maximum temperatures and more hot days, more heavy rainfall events, and, in some areas, an increase in peak wind intensities. What the warming climate will mean in detail for the South Pacific is still the subject of investigation by scientific researchers, with key emerging issues including changes in rainfall patterns and associated shifts in water resources and agricultural growing conditions. Following is a summary of knowledge gained in the past decade about the effect of climate change on New Zealand:

Projected climate changes – Temperatures in New Zealand are likely to increase faster in the North Island than in the South Island, but generally less than global average temperatures. Rainfall is projected to increase in the west of the country and to decrease in many eastern regions. In the long term, rising seas are expected to increase erosion of vulnerable beaches and breach coastal protection structures more often.

Agriculture – The agricultural sector could benefit from climate change, but also faces risks. The key benefit is likely to be from increased carbon dioxide concentrations, which could lead to greatly increased growth rates and water-use efficiency. In addition, warmer conditions and lengthened growing seasons could result in a long-term southward shift of climate-linked activities, and new crops and related industries could be introduced. The most significant risks include more droughts and floods in some areas, particularly in the east of New Zealand. Warmer temperatures could also make the growing of some current fruit crops in some northern areas uneconomical.

Native ecosystems – Climate change may add to pressures on ecosystems already under threat. Fragmented native forests of drier lowland environments in Northland, Waikato and Manawatu, and in the east from East Cape to Southland, are probably the most vulnerable to climate change.

Urban environment, transport and energy – The main threat to the urban environment comes from possible increases in heavy rainfall, which would put pressure on drainage and stormwater systems and increase the risk of flooding in some areas. Warmer conditions would substantially reduce home heating costs, leading to reduced electricity demand during the peak winter season, but possibly increased demand for air conditioning during summer. Wetter conditions on the West Coast could increase hydroelectricity production in winter.

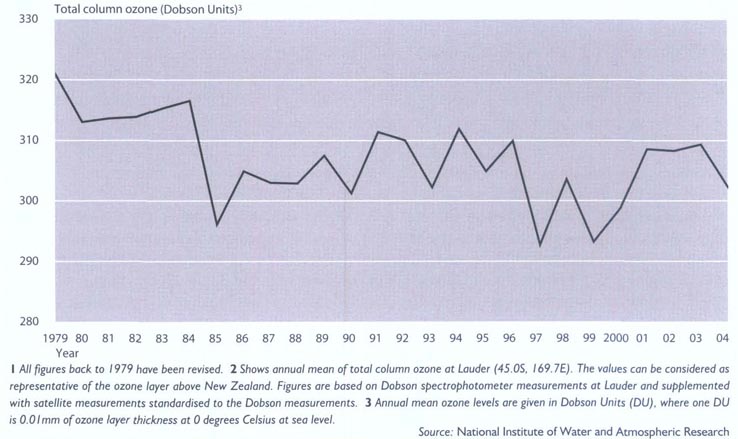

Health – Higher temperatures are expected to reduce winter illnesses, but could lead to higher death rates during summer. A warmer climate could also allow the spread of mosquitoes capable of transmitting diseases such as Ross River virus and dengue fever. Recent research has also found that climate change could lead to a delay in the recovery of the ozone layer. This would increase the period during which New Zealanders are exposed to high levels of ultraviolet radiation, which is known to lead to skin cancers. However, the possible effects of greenhouse gases on the ozone layer are still highly uncertain.

Table 1.06 lists predicted temperature and rainfall changes.

Table 1.06. Predicted changes in annual mean temperature and precipitation

Between 1970–1999 and

2070–2099

| Region | Temperature | Precipitation |

|---|---|---|

| Source: National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research | ||

| Northland, Auckland | +0.6° to +4.0°C | -16% to +7% |

| Western North Island from Waikato to Wellington | +0.3° to +3.8°C | -6% to +32% |

| Eastern North Island from Bay of Plenty to Wairarapa | +0.5° to +3.8°C | -32% to +4% |

| Nelson, Marlborough, Canterbury | +0.4° to +3.3°C | -21% to +5% |

| West Coast, Otago, Southland | +0.2° to +3.5°C | +1% to +57% |

Table 1.07 summarises New Zealand's climate extremes.

Table 1.07. Summary of New Zealand climate extremes

At 31 December 2005

| Rainfall | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Period | Amount mm | Location | Date |

| Source: National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research | |||

| Highest | |||

| 10 minutes | 34 | Tauranga | 17 April 1948 |

| 1 hour | 109 | Leigh | 30 May 2001 |

| 12 hours | 473 | Colliers Creek (Hokitika Catchment) | 22 January 1994 |

| 24 hours | 682 | Colliers Creek (Hokitika Catchment) | 21–22 January 1994 |

| 48 hours | 1,049 | Waterfall, Cropp River (Hokitika Catchment) | 12–13 December 1995 |

| 1 calendar month | 2,927 | Waterfall, Cropp River (Hokitika Catchment) | December 1995 |

| 1 calendar year | 16,617 | Waterfall, Cropp River (Hokitika Catchment) | January-December 1998 |

| 365 days | 18,442 | Waterfall, Cropp River (Hokitika Catchment) | 29 October 1997–29 October 1998 |

| Lowest: | |||

| 3 months | 9 | Cape Campbell | January-March 2001 |

| 6 months | 52 | Cape Campbell | Nov 2000–April 2001 |

| 12 months | 167 | Alexandra | Nov 1963–Oct 1964 |

| Longest rainless period: | |||

| 71 days | 0 | Wai-iti, Marlborough | From 8 Feb 1939 |

| Temperature | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Temperature (°C) | Date | |

| Highest air temperature | |||

| North Island | 39.2 | Ruatoria | 7 February 1973 |

| South Island | 42.4 | Rangiora | 7 February 1973 |

| Lowest air temperature | |||

| North Island | -13.6 | Chateau Tongariro | 7 July 1937 |

| South Island | -21.6 | Ophir | 3 July 1995 |

| Lowest grass minimum | -21.6 | LakeTekapo | 4 August 1938 |

| Sunshine | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Total (hours) | Date | |

| Highest in one year | |||

| North Island | 2,588 | Napier | 1994 |

| South Island | 2,711 | Nelson | 1931 |

| Highest in one month | |||

| North Island | 335 | Taupo | January 1950 |

| South Island | 336 | Nelson | December 1934 |

| Lowest in one year | |||

| North Island | 1,357 | Palmerston North | 1992 |

| South Island | 1,333 | Invercargill | 1983 |

| Lowest in one month | |||

| North Island | 27 | Taumarunui | June 2002 |

| South Island | 35 | Invercargill | June 1935 |

| Wind gusts | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Speed (km/h) | Date | |

| North Island | 248 | Hawkins Hill, Wellington | 6 November 1959 and 4 July 1962 |

| South Island | 250 | Mt John, Canterbury | 18 April 1970 |

New Zealand's climate in 2005 was marked by too little rain in some places and too much in others. Rainfall during the year was less than 75 percent of normal over much of the South Island, whereas severe flooding in the Bay of Plenty in May caused widespread damage.

The national average temperature of 13.1 degrees Celsius made 2005 the fourth warmest year nationally since reliable records began in the 1860s.

Notable climate features in various parts of the country included heat waves, low soil moisture, a tornado in Greymouth, unseasonable snowstorms and damaging hailstorms.

Anticyclones and northeasterlies brought one of the warmest Februaries on record, with maximum temperatures of 30 degrees Celsius or more in many locations throughout New Zealand and temperatures of 35 degrees Celsius or more in sheltered inland areas of the South Island.

Disastrous floods hit the Bay of Plenty in May, causing widespread damage in parts of Tauranga, with a state of emergency declared from there south to Matata. Hundreds of people were evacuated, with several homes destroyed by mudslides and floodwaters.

The winter of 2005 was the sixth warmest on record, with extremely dry conditions in the east of the South Island.

Overall, the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research reported at least 26 heavy rainfall events during 2005, half of which produced floods. There were seven damaging hailstorms and 12 damaging tornadoes. The Greymouth tornado of 10 March left 30 people homeless and caused damage of at least $10 million.

Wellington's airport was closed by fog for more hours in 2005 than in any other year, with 52 hours of fog recorded there.

The islands of New Zealand separated from their nearest neighbours more than 80 million years ago. They stretch across 24 degrees of latitude from the subtropical to the subantarctic, making New Zealand a slender archipelago with an extraordinary natural heritage born from its biological and geological isolation.

Some of the original inhabitants endured times of turbulent change and violent upheaval, evolving and adapting to become part of a unique natural biota (or region). Other species died out (either nationally or regionally), unable to compete or survive environmental disturbances such as ice ages. For example, coconut palms were once found in New Zealand, and kauri, now confined to the north of the North Island, used to grow as far south as Canterbury.

Over the years, the earliest inhabitants were joined by other plants and animals carried across the oceans by wind and current.

The pre-human environment was notable for the absence of snakes, land mammals (apart from three species of bat) and many of the flowering plant families. Whole orders and families were found only in New Zealand, including tuatara, moa and kiwi, all of the native lizards, and nearly 200 species of native earthworms.

Many remarkable plants, insects and birds evolved to fill ecological niches normally occupied by mammals. Others diversified to fill new territories created by sea-level fluctuations and land uplift.

With no mammalian predators on the ground, but avian predators everywhere, flightlessness was not a handicap, nor was size. Moa (11 species, some up to 3 metres tall) became extinct in pre-European times, but many other large flightless birds still remain, including kiwi, the nocturnal kākāpō (the only flightless parrot in the world) and weka (of the rail family).

Flightless insects are numerous, including many large beetles and 70 or so species of the cricket-like weta, found only in New Zealand.

New Zealand, with 84 species, has the most diverse seabird fauna of any country. Nearly half of all native bird species depend on the ocean for food, the feeding zones of some extending as far south as the Antarctic continent. New Zealand's extensive coastline and many islands offer a huge range of habitat, from estuary and mud-flat, to rocky cliffs and boulder bank.

The ocean is marvellously rich. There are about 400 different fish in the waters around New Zealand, as well as various species of seals, dolphins and porpoises. Twenty-nine species of whale have been recorded, and three of the largest (sperm, humpback and right) regularly migrate to New Zealand waters in spring and autumn.

The most widespread and complex type of forest in New Zealand is a podocarp (conifer) broadleaf association. It is generally found at lower altitudes and is characterised by a variety of species, a stratified canopy and an abundance of vines and epiphytic plants.

Beech and kauri forests, by contrast, are much simpler in structure. New Zealand's beech species have close relatives in Australia and South America and the five different types of species in New Zealand have exploited habitats from valley floor to mountain tops. Kauri, true forest giants, dominate only in the warmer climes to the north.

Some of the most specialised plants are those occupying the alpine zone. A remarkable 25 percent of all New Zealand's plants can be found above the treeline. Ninety-three percent of all alpine plants are found only in New Zealand, compared with 80 percent for the rest of the higher plant species. Snow tussock herbfields are one of the most distinctive elements in this cold, windswept environment. Remarkably long-lived, some larger specimens may be several centuries old. Like beech trees, they seed infrequently, but in profusion.

A definitive feature of New Zealand's land-based plants and animals is their degree of specialisation and narrow habitat requirements (e.g. takahē/tussock grasslands; blue duck/fast flowing rivers and streams) and their evolution in the absence of mammalian predators (birds) or browsers (plants). This specialisation, and adaptations which make New Zealand's wildlife so unique, render them extremely vulnerable to introduced predators, such as rats and cats; competitors, such as deer and possums; and loss of habitat.

The arrival of people in New Zealand heralded times of rapid change.

Introduction (intentionally or accidentally) of exotic plants and animals, and modification of habitat, radically affected native species populations.

In the pre-1800 period, following the arrival and expansion of Māori, forest cover was reduced and 34 species became extinct, including moa, the adzebill and the flightless goose.

In the much shorter post-1800 period of European settlement, the forest area was further reduced to around 25 percent of the land, nine more bird species became extinct and many more were threatened.

Since 1840, more than 80 new species of mammals, birds and fish, and more than 1,800 plant species have been introduced, in many places totally changing the landscape and ecology.

One uniform time is kept throughout mainland New Zealand. This time is 12 hours ahead of Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) and is called New Zealand Standard Time (NZST). It is an atomic standard maintained by the Measurement Standards Laboratory, part of Industrial Research Ltd, Lower Hutt.

One hour of daylight saving, called New Zealand Daylight Time (NZDT), which is 13 hours ahead of UTC, is observed from 2am (NZST) on the first Sunday in October, until 2am (NZST) on the third Sunday in March.

Time kept in the Chatham Islands is 45 minutes ahead of that kept in New Zealand.

1.1 Land Information New Zealand; National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research.

1.2 GNS Science.

1.3 National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research.

1.4 Department of Conservation.

1.5 Industrial Research Ltd.

Table of Contents

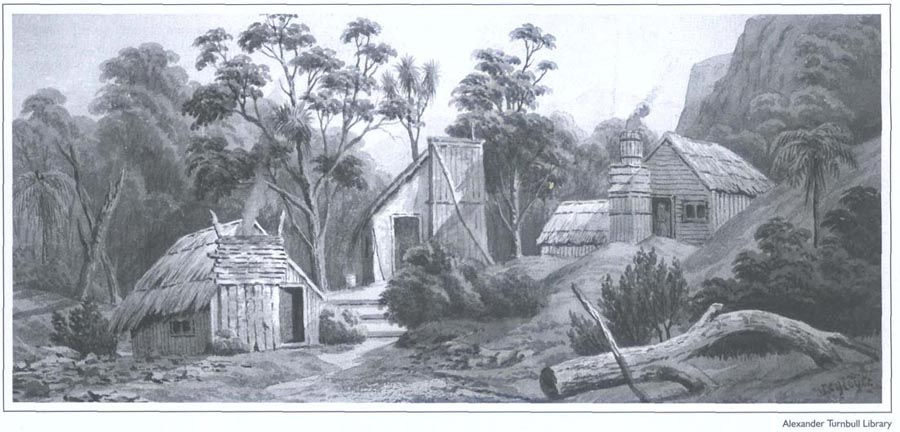

Miners’ slab huts in a bush clearing in the Coromandel district between 1864 and 1867. From a watercolour by John Barr Clark Hoyte (1835–1913).

New Zealand has a shorter human history than any other country. The precise date of settlement is a matter of debate, but current understanding is that the first arrivals came from East Polynesia in the 13th century. It was not until 1642 that Europeans became aware the country existed.

The original Polynesian settlers discovered the country on deliberate voyages of exploration, navigating by ocean currents, winds and stars. The navigator credited in some traditions with discovering New Zealand is Kupe. Some time later, the first small groups arrived from Polynesia. Now known as Māori, these tribes did not identify themselves by a collective name until the arrival of Europeans when, to mark their distinction, the name Māori, meaning ‘ordinary’, came into use.

The early settlers lived in small hunting bands. Seals and the large flightless moa bird were their main prey, until moa were hunted to extinction.

In the South Island, hunting and gathering remained the main mode of survival, but the kūmara (sweet potato) and yams the Polynesians brought with them grew well in the warmer North Island. Extensive kūmara gardens supported relatively large settlements. But even in the north, birds, fish and shellfish were important in the Māori diet. In some northern areas, larger populations put pressure on resources. The Polynesian dog and rat came with the early arrivals, but the domestic pigs and chickens of the islands did not, for reasons not fully understood.

In favourable conditions, Māori lived reasonably well. Their life expectancy was low by modern standards, but probably comparable with that of Europeans in the same era. The Māori population before European contact may have reached 100,000.

Māori passed on rich and detailed history and legends orally. Society was organised around groups that traced their descent from common ancestors. Reciting whakapapa (genealogies) was an important way to communicate knowledge.

The concepts of mana (status) and utu (reciprocity) were central to the culture, and led to widespread warfare. But the violence was usually episodic. For most of the time, Māori lived not in fortified pā, but in unprotected settlements or seasonal camps.

The greatest achievements of Māori material culture were carving wood for important buildings and canoes, and fashioning stone into tools and ornaments. Warfare did not inhibit regular trade in desirable stones and foods, and was itself a means by which resources were appropriated.

In 1642, Dutch explorer Abel Tasman made the first confirmed European discovery of New Zealand. He charted the country's west coast from about Hokitika up to Cape Maria van Diemen. Subsequently, a Dutch map maker gave the name Nieuw Zeeland to the land Tasman had discovered. A surprisingly long time – 127 years – passed before another European reached New Zealand.

James Cook first visited New Zealand in 1769, on the first of three voyages. He circumnavigated and mapped both main islands and returned to Britain with reports about the country's inhabitants and resources.

For 50 years after Sydney was founded in 1788, New Zealand was an economic and cultural outpost of New South Wales, and most of the earliest European settlers came from Sydney. In the late 18th century, sealers and whalers began visiting, and by the early 19th century some began to settle, some to farm. During these years, New Zealand was part of a Pacific-wide trade system and New Zealand goods were sold in China.

The first European ‘town’ grew at Kororāreka when whalers began calling into the Day of Islands for food and water. From the 1790s, Māori produced pork and potatoes for this trade. The other main area of early interaction between Māori and others was the Foveaux Strait sealing grounds.

The presence of traders drew Māori to particular locations. Having a European living among them gave some tribal groups an advantage in the race to acquire European goods, especially firearms.

A Sydney chaplain, Samuel Marsden, founded the first Christian mission station in the Bay of Islands in 1814. By 1840, more than 20 stations had been established. From missionaries, Māori learnt not just about Christianity, but also about European farming techniques and trades, and how to read and write. The missionaries also transcribed the Māori language into written form. In the 1830s, French missionaries brought Catholicism to Māori.

Christianity would become important for Māori, but they were slow to convert. Muskets, traded for flax and potatoes, had a greater impact in the 1820s and 1830s than religion, and escalated killings in tribal conflicts. The Ngā Puhi tribe, led by Hongi Hika, devastated southerly tribes, and Ngāti Toa, under Te Rauparaha, attacked Ngai Tahu in the South Island. But diseases introduced by Europeans caused more fatalities than firearms.

In the 1830s, the British Government came under increasing pressure to curb lawlessness in New Zealand to protect British traders, and to forestall the French, who also had imperial ambitions. The missionaries, for their part, wanted to protect Māori from the effects of European settlement.

In 1833, James Busby was sent to the Bay of Islands as British Resident. At Busby's instigation, northern chiefs adopted a flag in 1834 and signed a declaration of independence in 1835. Seven years after Busby's arrival, at Waitangi on 6 February 1840, William Hobson, New Zealand's first governor, invited assembled Māori chiefs to sign a treaty with the British Crown. The treaty was taken all round the country, as far south as Foveaux Strait, for signing by local chiefs, and eventually more than 500 signed.

Under the treaty, Māori ceded powers of government to Britain in return for the rights of British subjects and guaranteed possession of their lands and other ‘treasures’. In later years, differences of interpretation between the English and Māori texts complicated efforts to redress breaches of the treaty.

British sovereignty was proclaimed over New Zealand on the basis of Māori consent, though the South Island was initially claimed on the basis of discovery.

In the 19th century, the British and the French were rivals in the Pacific. The French had only minor interests in New Zealand, but the myth persists that the South Island escaped being French only because in the scramble to colonise Akaroa the British got there first. But by the time the French settlers and their naval escort reached New Zealand, the whole country was securely British. Governor Hobson, learning the French were heading for Akaroa, did send Captain Stanley of the Britomart to demonstrate British sovereignty there. However, there was never any chance Cook Strait would become, like the English Channel, a passage between English and French-speaking regions.

Even before the Treaty of Waitangi had been signed, the New Zealand Company, inspired by the colonial promoter Edward Gibbon Wakefield, had despatched British settlers to Wellington. In the next two years, the company also founded Wanganui, Nelson and New Plymouth. Otago was founded in 1848 and Canterbury in 1850, both by New Zealand Company affiliates. Auckland, capital of the new Crown colony, grew independently.

By the 1850s, most of the interior of the North Island had been explored by Europeans. Māori guides usually showed European explorers the way and New Zealand's first Anglican bishop, George Selwyn, travelled widely. Much of the mountainous interior of the South Island was not explored until gold miners arrived in the 1860s.

When British settlers sought self-government, the British parliament passed the New Zealand Constitution Act of 1852, setting up a central government with an elected House of Representatives and six provincial governments. The settlers soon won the right to responsible government (with an executive supported by a majority in the elected assembly). But the governor, and through him the Colonial Office in London, retained control of ‘native’ policy.

In the 1840s, there were clashes between Māori and Pākehā. In Marlborough's Wairau Valley in 1843, a dispute over land erupted, leading to bloodshed. The war in the north (1845–46) began when Hōne Heke cut down the flagpole flying the British flag at Russell. There were also troubles in the 1840s over land in Wellington and Wanganui. In the 1850s, disputes between Māori over the sale of land to Europeans kept Taranaki in ferment.

Until the late 1850s, the government managed to purchase enough land to meet settler demands. But many Māori became increasingly reluctant to sell their land, which tribes owned collectively. The Māori King movement, under the leadership of Wiremu Tāmihana, grew in part out of Māori resistance to land sales. Pōtatau Te Wherowhero was elected the first Māori King in 1858.

The flashpoint was Taranaki. The refusal of Wiremu Kīngi Te Rangitāke to sell land at Waitara led to war in 1860. The efforts of Māori to retain their land were depicted by the settlers as a challenge to British sovereignty.

Māori resistance was effectively crushed after Governor George Grey took war to the Waikato in 1863–64.

Two chiefs, Te Kooti and Titokowaru, prolonged war through the 1860s, but by 1872 the wars over land had ended. Large areas of land were confiscated from ‘rebellious’ tribes. A Native Land Court gave land titles to individual Māori, to facilitate sales to Pākehā.

After the wars, many Māori drew back from contact with European settlers. Most lived in isolated rural communities. Māori land continued to pass into Pākehā hands, usually by sale through the Native Land Court. In the 1870s, the village of Parihaka became the centre of a peaceful protest, led by the prophet Te Whitio-Rongomai, against occupation of confiscated land in Taranaki. In 1881, government forces invaded Parihaka in an attempt to crush this resistance.

While progress in the North Island was held back by war, the South Island forged ahead on the proceeds of wool and gold. Sheep were turned loose on South Island grasslands and after gold had been discovered in Otago in 1861, and then on the West Coast, settlers flooded in. Six years later, the discovery of gold at Thames boosted the town of Auckland. Wool ensured that Canterbury became the wealthiest province, and gold made Dunedin the largest town.

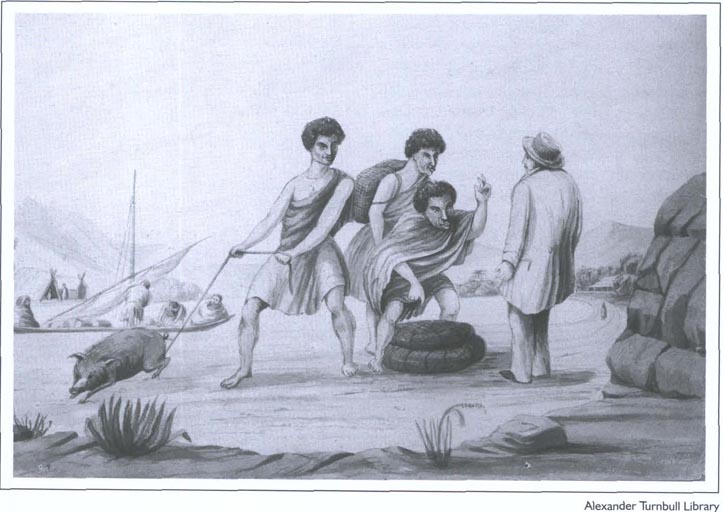

Māori with baskets of potatoes and a pig bargain with a European trader around 1845. From a drawing by John Williams.

The Giant Buttress, part of the pink and white terraces at Lake Rotomahana destroyed in the Mt Tarawera eruption of 1886.

Towards the end of the 1860s, gold production fell and wool prices slipped. A new boost to growth came in 1870 when Colonial Treasurer Julius Vogel proposed a loans-funded programme of public works, including the building of railways, and assisted immigration.

The population increased dramatically. The census (non-Māori) of 1871 recorded a total of about 250,000; 10 years later this had grown to half a million. Vogel's policies, like those of Wakefield before him, were based on a belief that New Zealand would grow only if people and capital could be attracted. This stimulated a sense of a single nation rather than separate settlements, and led to the abolition of the provinces in 1876.

The aftermath of Vogel's borrowing was an economic depression that lasted into the 1890s. Despite a brief boom in wheat, prices for farm products sagged and the market for land became depressed. Hard times led to urban unemployment and sweated labour in industry. The country lost people through emigration, mostly to Australia.

Scarcely had depression gripped the country than future prosperity was anticipated with the first successful shipment of frozen meat to England in 1882. Exporting meat (frozen) and butter and cheese (chilled) became possible. After dealing with initial setbacks in refrigerated shipping, New Zealand became a British farm. With an economy based on agriculture, the landscape was transformed from forest to farmland.

The watershed election of 1890 put the Liberals, New Zealand's first ‘modern’ political party, into power. From 1893 to 1906, the government was headed by ‘King Dick’ Seddon. The Liberals cemented in place New Zealand's ‘family farm’ economy by subdividing large estates, buying Māori land in the North Island, and offering advances to settlers. Buoyant markets for New Zealand's farm products ensured the success of these policies. The Minister of Lands, John McKenzie, championed the family farm. Farming progressed, especially in the north, and by 1901, more than half the European population was living north of Cook Strait for the first time since the 1850s.

The Liberal government reinforced an established pattern of state involvement in the economy and regulation of society. Its old-age pensions and workers’ dwellings anticipated the welfare state. In 1893, after campaigns led by women like Kate Sheppard, New Zealand became the first country in the world to give women the vote.

New Zealand's close economic ties with Britain reinforced the loyalty of New Zealanders to an empire that secured their place in the world. The loyalty found expression in the despatch of troops to fight for Britain in South Africa in 1899. A self-confident nationalism was also evident, and New Zealand declined to join the Australian Federation of 1901.

Liberal rule ended in 1912, when William Massey led the Reform Party to power, promising state leaseholders they could freehold their land.

When World War I broke out, New Zealand rallied to England's aid. Thousands of New Zealanders served, and died, overseas. The 1915 landing at Gallipoli in Turkey was a coming of age for the country and established the potent tradition of ANZAC (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) – a pride in New Zealand's military achievement and its special relationship with Australia. New Zealand troops also fought and died on the Western Front.

After some prosperous years in the later 1920s, the worldwide Great Depression hit New Zealand hard. Export prices collapsed. Farmers faced difficulties over their mortgages and urban unemployment soared. Discontent erupted in riots. A coalition government, dominated by Gordon Coates, failed to lift the country out of depression.

Organised labour flexed its muscle in the 1890 maritime strike and in the Waihī and watersider strikes of 1912–13. Setbacks on the industrial front turned the labour movement towards political action. The Labour Party, founded in 1916, made uneven gains through the 1920s, then was swept into power under Michael Joseph Savage in 1935 by an electorate disillusioned with how the conservative coalition government had handled the depression. When Savage died in 1940, Peter Fraser became prime minister.

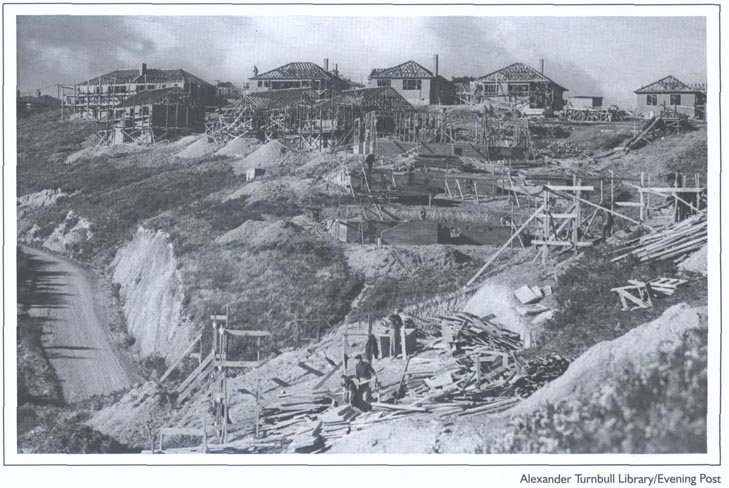

In power, the Labour Party, aided by an economic recovery already underway when it was elected, revived the economy further by pragmatic rather than doctrinaire socialist policies. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand was taken over by the state in 1936, spending on public works increased and a state housing programme began. The Social Security Act 1938 dramatically extended the welfare state.

With the outbreak of World War II, New Zealand troops again fought overseas in support of the United Kingdom. The fall of Singapore shook New Zealanders’ confidence that Britain could guarantee the country's security. During the war in the Pacific, the United States protected New Zealand against Japan.

Labour remained in power through World War II and in 1945, Peter Fraser played a significant role in the conference that set up the United Nations. But the party had lost the reforming zeal of the previous decade and its electoral support ebbed after the war.

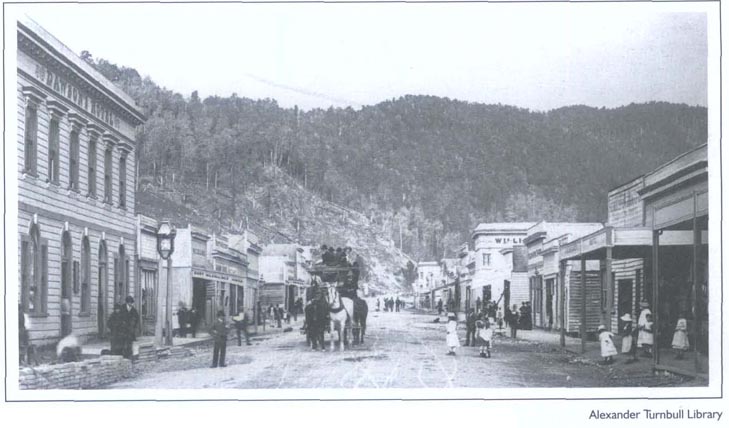

Coach and business premises on Broadway, Reefton, in the 1880s.

In the early 1950s, New Zealand troops fought in Korea. Later, in the 1960s, concern to keep on side with this new protector prompted the National government of Keith Holyoake to send troops to Vietnam, despite popular protests.

After Labour lost power in 1949, the conservative National Party ruled the country until 1984, interrupted by two single-term Labour governments, in 1957–60 and 1972–75. National Party Prime Minister Sidney Holland used the bitter 1951 waterfront strike to consolidate his power by calling a snap election.

New immigrants, still mainly British, flooded in while New Zealand remained prosperous by exporting farm products to Britain. The country's culture remained based on Britain's. In 1953 New Zealanders took pride that a countryman, Edmund Hillary, gave Queen Elizabeth II a coronation gift by reaching the summit of Mt Everest.

Britain joined the European Economic Community in 1973. New Zealand had already diversified its export trade, but the loss of an assured market for farm products was a blow.

The first oil shock of 1973 contributed to the fall of the Labour government in 1975, led until his death by Norman Kirk. After the second oil shock of 1978, the National government of Robert Muldoon tried to keep New Zealand prosperous by so-called ‘think big’ industrial and energy projects, and farm subsidies. The economy faltered as the fall of oil prices in the early 1980s made these schemes unsound. Inflation and unemployment mounted.

The fourth Labour government was elected in 1984. The Minister of Finance, Roger Douglas, was an ardent advocate of economic liberalisation. He removed most controls over the economy, privatised many state enterprises and called aspects of the welfare state into question. Many saw these measures as an assault on New Zealand's egalitarian traditions.

In foreign affairs, Labour's anti-nuclear policy ruptured relations with the United States.

The National government of 1990–99 pursued similar policies to Labour's, passing the controversial Employment Contracts Act which opened up the labour market and diminished the power of trade unions. The government also mounted a more sustained attack on the welfare state, most obviously by cutting benefits.

After the 1996 introduction of a new voting system (mixed member proportional representation), minority or coalition governments became the norm, but National and Labour remained the major parties.

Most Māori continued to live in remote rural communities until World War II. But Māori society was dynamic. The Kotahitanga movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries was evidence of Māori resilience. So were the land development work of āpirana Ngata and the revitalisation of the Māori King movement by Te Puea Hērangi. In the early 1920s, Wiremu Rātana founded the Rātana Church.

Post-World War II Māori migration into the cities, together with Māori anger at their economic deprivation and concern about their mana and continuing loss of land, pushed race relations and the place of the Treaty of Waitangi into the forefront of national life.

For many, sporting contacts with apartheid South Africa became a touchstone of race relations. During the 1981 Springbok rugby tour, New Zealand experienced divisive unrest. After the tour, attention turned to domestic race relations and to the need for New Zealanders to have a better understanding of the Treaty of Waitangi.

Māori became more assertive. Some, alleging breaches of the Treaty of Waitangi, wished to reclaim Māori sovereignty. The Waitangi Tribunal was set up in 1975 to consider their claims and to address grievances. In 1985, the tribunal was empowered to look at breaches of the treaty since 1840, rather than since 1975.

A Māori cultural renaissance, including efforts to foster the Māori language in the early 1980s, increased awareness that New Zealand society was bicultural. At the same time, more immigrants were arriving.

Almost before it had been properly acknowledged that New Zealand was bicultural, it became multicultural – first in the composition of its population, more slowly in how it ran its national life. The country's new Pacific Island and Asian citizens were testament to the fact that it was no longer, culturally or economically, the offshore island of Europe it had seemed to earlier generations.

John Wilson, Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand

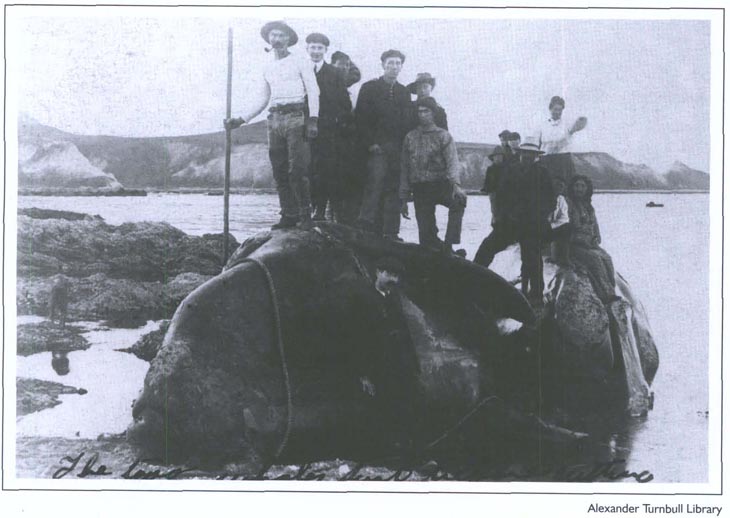

Two whales brought ashore at Kaikoura around 1910.

| c1300 | Archaeological evidence indicates Polynesian settlement of New Zealand established by this date. |

| 1642 | Dutch explorer Abel Janszoon Tasman discovers a land he calls Staten Landt, later named Nieuw Zeeland. |

| 1769 | British explorer James Cook makes first of three visits to New Zealand, taking possession of the country in the name of King George III. |

| 1790s | Sealing, deep-sea whaling, flax and timber trading begins, with some small temporary settlements. First severe introduced epidemic among Māori population. |

| 1791 | First visit by a whaling vessel, the William and Ann, to Doubtless Bay. |

| 1806 | First Pākehā women arrive in New Zealand. |

| 1814 | British missionary Samuel Marsden makes first visit to New Zealand. Anglican mission station established. Sheep, cattle, horses and poultry introduced. |

| 1815 | First Pākehā child, Thomas Holloway King, born in New Zealand. |

| 1819 | Raids on Taranaki and Te Whanganuia-Tara regions by Ngā Puhi and Ngāti Toa people led by chiefs Patuone, Nene, Moetara, Tuwhare and Te Rauparaha. |

| 1820 | Ngā Puhi chief Hongi Hika visits England, meets King George IV and secures supply of muskets. |

| 1821 | Musket wars begin with raids by Hongi Hika and Te Morenga on southern iwi and continue throughout the decade. |

| 1822 | Ngāti Toa migration south to Cook Strait region, led by Te Rauparaha, begins. |

| 1823 | Wesleyan Missionary Society mission established. First Church of England marriage between Pākehā and Māori – Phillip Tapsell and Maria Ringa. |

| 1824 | Te Heke Niho-Puta migration of Taranaki iwi to the Kapiti Coast. Rawiri Taiwhanga in Bay of Islands sells dairy produce and other food supplies to visiting ships. |

| 1827 | Te Rauparaha's invasion of the South Island from Kapiti begins. |

| 1831 | Whaling stations established at Tory Channel and Preservation Inlet. |

| 1833 | James Busby arrives in the Bay of Islands to take up appointment as British Resident in New Zealand. |

| 1834 | United Tribes’ flag adopted by some 25 northern chiefs at Busby's suggestion. |

| 1835 | Declaration of Independence by the ‘United Tribes of New Zealand’ signed by 34 northern chiefs. |

| 1837 | New Zealand Association formed in London, becoming the New Zealand Colonisation Society in 1838 and the New Zealand Company in 1839, under the inspiration of Edward Gibbon Wakefield. William Colenso completes printing the New Testament in Māori, the first book printed in New Zealand. |

| 1838 | Bishop Pompallier founds Roman Catholic mission at Hokianga. |

| 1839 | William Hobson instructed to establish British rule in New Zealand, as a dependency of New South Wales. Colonel William Wakefield, of the New Zealand Company, arrives on the Tory to purchase land for settlement. |

| 1840 | Treaty of Waitangi signed at Bay of Islands and later over most of the country. British sovereignty proclaimed. Hobson becomes first governor and sets up executive and legislative councils. New Zealand Company settlers arrive at Port Nicholson, Wellington. French settlers land at Akaroa. Local Māori initially provide food for these and later settlements. |

| 1841 | European settlements established at New Plymouth and Wanganui. Capital shifted from Russell to Auckland. |

| 1842 | Main body of settlers arrive at Nelson. |

| 1843 | Twenty-two European settlers and four Māori killed at a confrontation at Tua Marina, near Wairau, in Marlborough. Robert FitzRoy becomes governor. |

| 1844 | New Zealand Company suspends colonising operations due to financial difficulties. |

| 1845 | Hōne Heke begins war in the north. George Grey becomes governor. Half of all adult Māori are at least partly literate. |

| 1846 | War in the north ends with capture of Ruapekapeka. Fighting between Māori and Pākehā around Wellington. Te Rauparaha captured by Grey. First New Zealand Constitution Act passed. Heaphy, Fox and Brunner begin exploring the West Coast, First steam vessel, HMS Driver, arrives in New Zealand. |

| 1848 | Settlement founded by Scottish Otago Association. Provinces of New Ulster and New Munster established. Coal discovered at Brunner on the West Coast. Earthquake centred in Marlborough damages most Wellington buildings. |

| 1850 | Canterbury settlement founded. |

| 1852 | Second New Zealand Constitution Act passed creating general assembly and six provinces with representative government. |

| 1853 | Idea of a Māori King canvassed by Tamihana Te Rauparaha and Matene Te Whiwhi. Many Māori agree not to sell any more land – 32 million acres have been bought by the government in the past five years. |

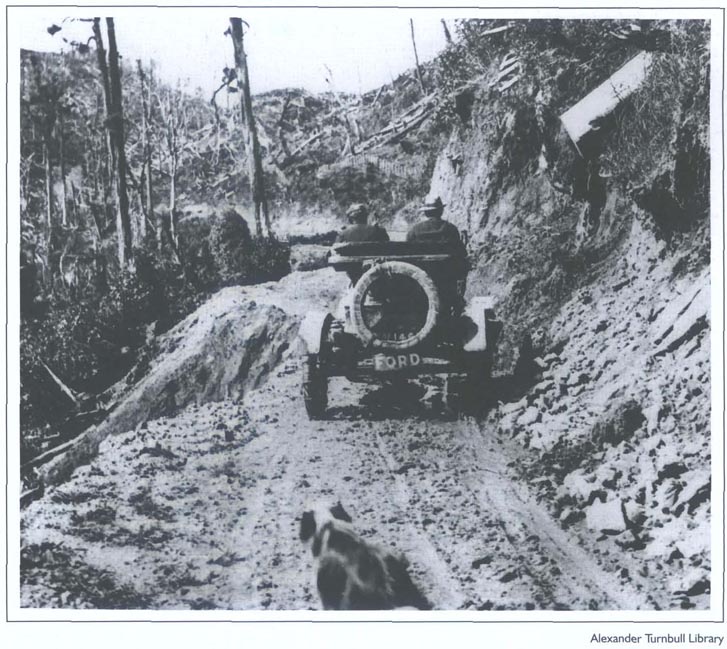

A Ford car on a King Country road during the first motor trip from Wellington to Auckland in 1912. | |

| 1854 | First session of general assembly opens in Auckland. |

| 1855 | Governor Thomas Gore Browne, appointed in 1854, arrives. Severe earthquake on both sides of Cook Strait. |

| 1856 | Henry Sewell forms first ministry under responsible government and becomes first premier. Edward Stafford forms first stable ministry. |

| 1858 | New Provinces Act passed. Te Wherowhero installed as first Māori King, taking name Potatau I. |

| 1859 | First session of new Hawke's Bay and Marlborough provincial councils. Gold discovered in Buller River. |

| 1860 | Waitara dispute develops into general warfare in Taranaki. Te Wherowhero dies and is replaced as Māori King by his son, Tawhiao. Kohimaramara Conference of Chiefs. |

| 1861 | Grey begins second governorship. Gold discovered at Gabriel's Gully and Otago goldrushes begin. First session of Southland provincial council. Bank of New Zealand incorporated at Auckland. |

| 1862 | First electric telegraph line opens – from Christchurch to Lyttelton. First gold shipment from Dunedin to London. |

| 1863 | War resumes in Taranaki and begins in Waikato when General Cameron crosses the Mangatawhiri Stream. New Zealand Settlements Act passed to effect land confiscation. First steam railway in New Zealand opened. |

| 1864 | War in the Waikato ends after battle of Orakau. Māori defeat British at Gate Pa, Tauranga. Land in Waikato, Taranaki, Bay of Plenty and Hawke's Bay confiscated. Gold discovered in Marlborough and Westland. Arthur, George and Edward Dobson are the first Pākehā to cross what becomes known as Arthur's Pass. |

| 1865 | Seat of government transferred from Auckland to Wellington. Native Land Court established. Māori resistance continues. Auckland streets lit by gas for first time. |

| 1866 | Cook Strait submarine telegraph cable laid. Cobb and Co coaches start running from Canterbury to the West Coast. |

| 1867 | Thames goldfield opens. Four Māori seats established in parliament. Lyttelton railway tunnel completed. Armed constabulary established. |

| 1868 | Māori resistance continues through campaigns of Te Kooti Arikirangi and Titokowaru. New Zealand's first sheep breed, the Corriedale, developed. |

| 1869 | New Zealand's first university, the University of Otago, established. |

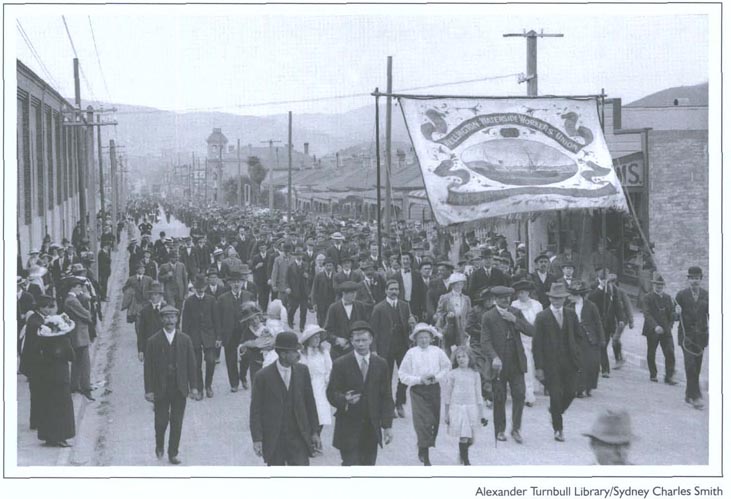

Striking workers and their supporters march through Newtown, Wellington, during a 1913 waterfront dispute. | |

| 1870 | Last imperial forces leave New Zealand. Vogel's public works and immigration policy begins. New Zealand University Act passed, establishing a federal system which lasts until 1961. Vogel announces national railway construction programme; more than 1,000 miles constructed by 1879. First rugby match in New Zealand played at Nelson. Auckland to San Francisco mail service begins. |

| 1871 | Deer released in Otago. |

| 1872 | Te Kooti retreats to the King Country and Māori armed resistance ceases. Telegraph communication links Auckland, Wellington and southern provinces. |

| 1873 | New Zealand Shipping Company established. |

| 1876 | Abolition of the provinces and establishment of local government by counties and boroughs. New Zealand–Australia telegraph cable established. |

| 1877 | Education Act passed, establishing national system of primary education. |

| 1878 | Completion of Christchurch–Invercargill railway. |

| 1879 | Triennial Parliaments Act passed. Vote is given to every male aged 21 and over. Kaitangata mine explosion, 34 people die. Annual property tax introduced. |

| 1881 | Parihaka community forcibly broken up by troops. Te Whiti, Tohu Kakahi and followers arrested and imprisoned. Wreck of SS Tararua, 131 people die. Auckland and Christchurch telephone exchanges open. |

| 1882 | First shipment of frozen meat leaves Port Chalmers for England on the Dunedin. |

| 1883 | Te Kooti pardoned; Te Whiti and other prisoners released. Direct steamer link established between New Zealand and Britain. |

| 1884 | King Tawhiao visits England with petition to the Queen and is refused access. First overseas tour by a New Zealand rugby team, to New South Wales. Construction of King Country section of North Island main trunk railway begins. |

| 1886 | Mt Tarawera erupts and Pink and White Terraces destroyed, 108 people die. Oil discovered in Taranaki. |

| 1887 | New Zealand's first national park, Tongariro, is presented to the nation by Te Heuheu Tukino IV. Reefton becomes first town to have electricity. First inland parcel post service. |

| 1888 | Birth of writer Katherine Mansfield. |

| 1889 | Abolition of non-residential or property qualification to vote. First New Zealand-built locomotive completed at Addington. |

| 1890 | Maritime strike involves 8,000 unionists. ‘Sweating’ Commission reports on employment conditions. First election on a one-man one-vote basis. |

| 1891 | John McKenzie introduces the first of a series of measures to promote closer land settlement. John Ballance becomes premier of first Liberal government. |

| 1892 | First meeting of national Kotahitanga Māori parliament. The Kingitanga sets up its own Kauhanganui parliament. |

| 1893 | Franchise extended to women. John Ballance dies and is succeeded by Richard John Seddon. Liquor licensing poll introduced. Elizabeth Yates becomes New Zealand's first woman mayor, of Onehunga. Banknotes become legal tender. |

| 1894 | Compulsory arbitration of industrial disputes and reform of employment laws. Advances to Settlers Act. Clark, Fyfe and Graham become the first people to climb Mt Cook. |

| 1896 | Brunner mine explosion, 67 people die. Census measures national population as 743,214. |

| 1897 | First of series of colonial, and later imperial, conferences in London. |

| 1898 | Old Age Pensions Act passed. First cars imported to New Zealand. |

| 1899 | New Zealand army contingent sent to South African war. First celebration of Labour Day. |

| 1900 | Māori Councils Act passed. Public Health Act passed setting up Department of Public Health in 1901. |

| 1901 | Cook and other Pacific islands annexed. Penny postage first used. |

| 1902 | Pacific cable begins operating between New Zealand, Australia and Fiji. |

| 1903 | Richard Pearse achieves semi-controlled flight near Timaru. |

| 1905 | The ‘Originals’ rugby team tours Britain and becomes known as the All Blacks. |

| 1906 | Seddon dies and is succeeded by William Hall-Jones as prime minister. |

| 1907 | New Zealand constituted as a dominion. Fire destroys parliament buildings. |