Te Pukapuka Houanga Whaimana o Aotearoa

Statistics New Zealand

Statistics New Zealand operates an information service. In answer to a letter, email, visit, or telephone call, information analysts can provide statistical information, or tell you more about the department's other services, including access to statistics on the INFOS computer database and the SNZ website.

Website: www.stats.govt.nz

Email:

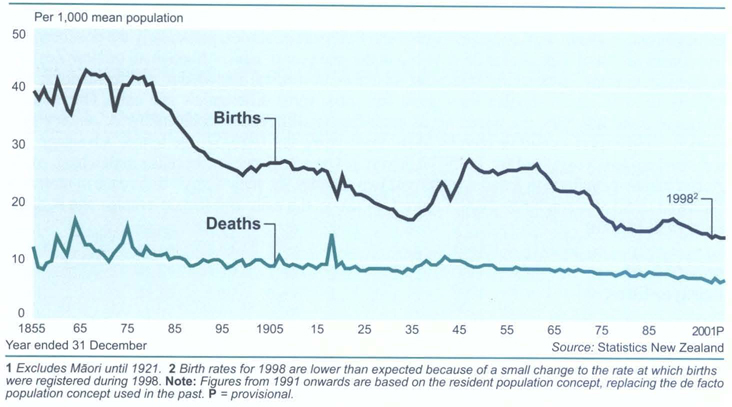

info@stats.govt.nz

70 Symonds Street, AUCKLAND

Private Bag 92003, Telephone +64-9-357 2100, Facsimile +64-9-379

0859

Aorangi House, 85 Molesworth Street, WELLINGTON

PO Box 2922, Telephone +64-4-495 4600, Facsimile

+64-4-495 4610

Dollan House, 401 Madras Street, CHRISTCHURCH

Private Bag 4741, Telephone +64-3-374 8700,

Facsimile +64-3-374 8864

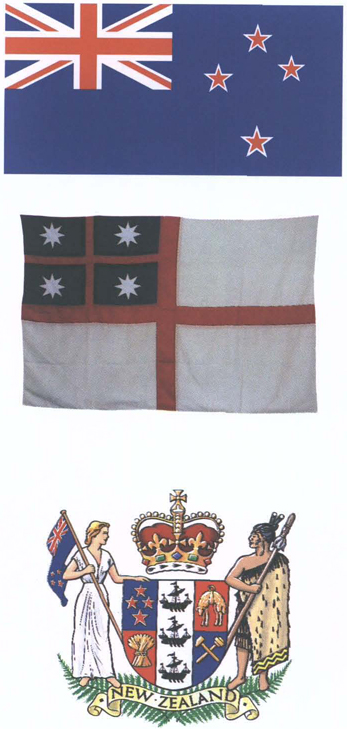

The New Zealand flag

The New Zealand flag is the symbol of the realm, government and people of New Zealand. The flag features, on a royal blue background, a Union Jack in the first quarter and four five-pointed red stars of the Southern Cross on the fly. The stars have white borders. Its royal blue background is reminiscent of New Zealand's blue sea and clear sky, while the stars of the Southern Cross emphasise New Zealand's location in the South Pacific Ocean. The Union Flag gives recognition to New Zealand's historical foundations and the fact that the country was once a British colony and dominion.

Te Hakituatahi o

Aotearoa

The first flag of New Zealand 1835

For a detailed history of Te Hakituatahi o Aotearoa, see Chapter 3: Government. Heraldic description: on a white field, a red St George's Cross; in the upper canton, next to the staff on a blue field, a smaller St George's Cross in red, severed from the blue by a fimbriation of black, half the width of the red and in the centre of each blue quarter a white eight-point star.

The New Zealand coat of arms

New Zealand has had its own coat of arms since 1911. Prior to that the United Kingdom coat of arms (featuring a lion and a unicorn on either side of a shield and crown) was used. This design still adorns the top of the pediment on the Old Government Buildings in Lambton Quay, Wellington, which were built in 1875 to house the colony's public service, but which now house Victoria University's law school. One of the few specific changes to flow on from the granting of dominion status in 1907, was the right for New Zealand to have its own coat of arms. The design was approved by royal warrant on 26 August 1911. The coat of arms was revised in 1956 following further constitutional changes when the country became the ‘Realm of New Zealand’ instead of ‘Dominion’. Accordingly, the British lion holding aloft the Union Jack was replaced by St Edward's Crown, which had been worn by Queen Elizabeth II at her coronation. At that same time, the dress of the figures at the side of the shield was revamped, some Victorian-looking scroll work at the base of the design was replaced by two ferns, and the motto ‘onward’ was replaced by ‘New Zealand’.

New Zealand Official Yearbook 2002

ISSN 0078 0170

ISBN

1-86953-517-0

This book is copyright. Except for the purpose of fair review, no part may be stored or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including recording or storage in any information retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publishers. No reproduction may be made, whether by photocopying or by any other means, unless a licence has been obtained from the publisher or its agent.

Copyright © Statistics New Zealand 2002.

Published in 2002 by David Bateman Ltd, 30 Tarndale Grove, Albany, Auckland, New Zealand.

Printed by PrintLink, Wellington, New Zealand.

Table of Contents

List of Figures

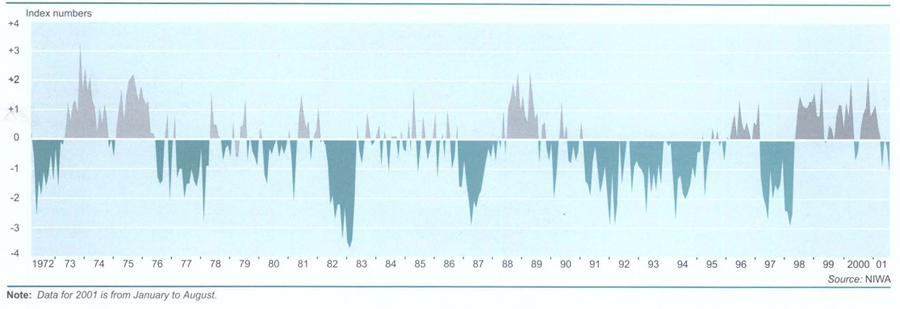

- 1.1. Weather

- 11.1. Internet activities 2001

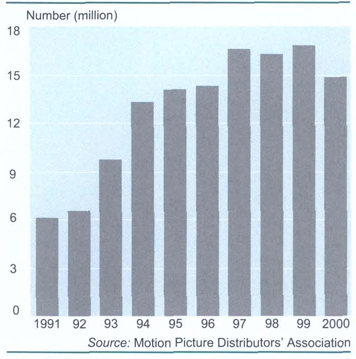

- 12.1. Cinema admissions

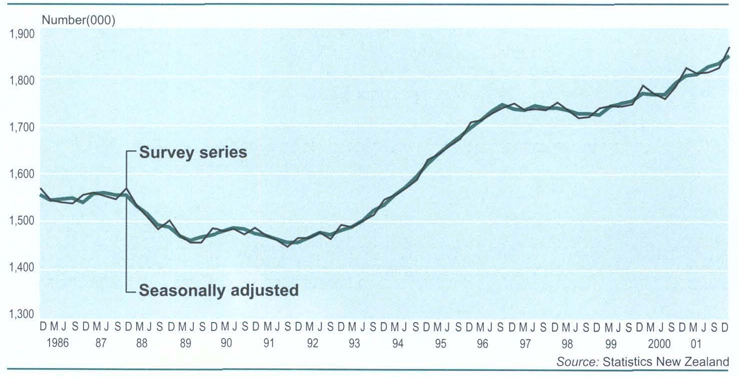

- 14.5. Employment

- 16.1. Land use

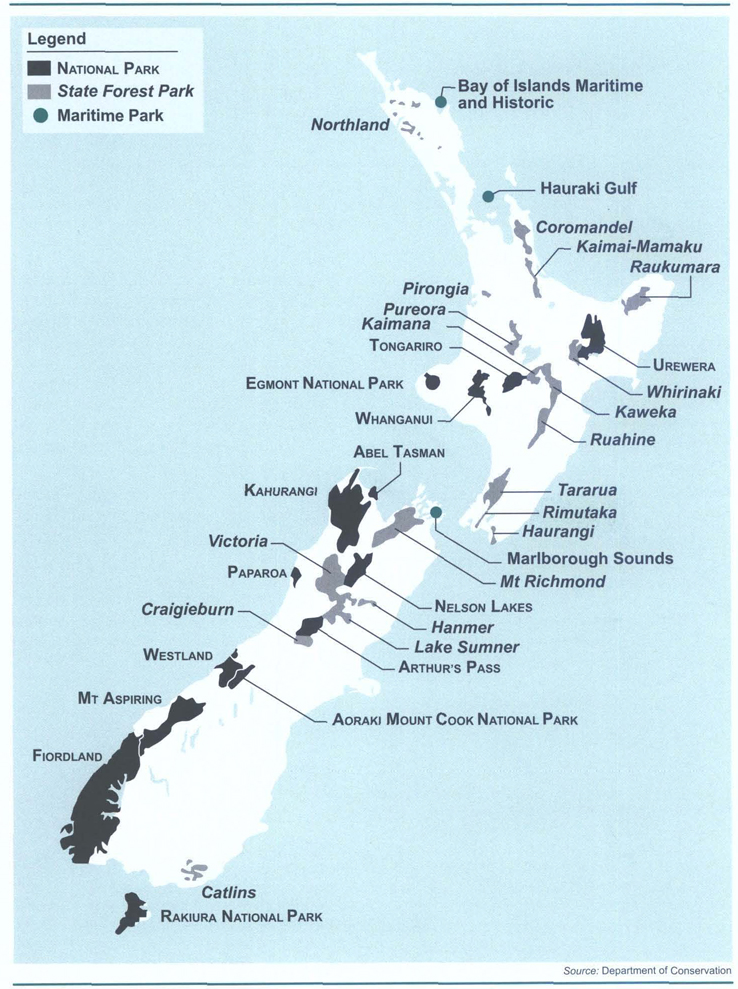

- 16.6. Parks of New Zealand

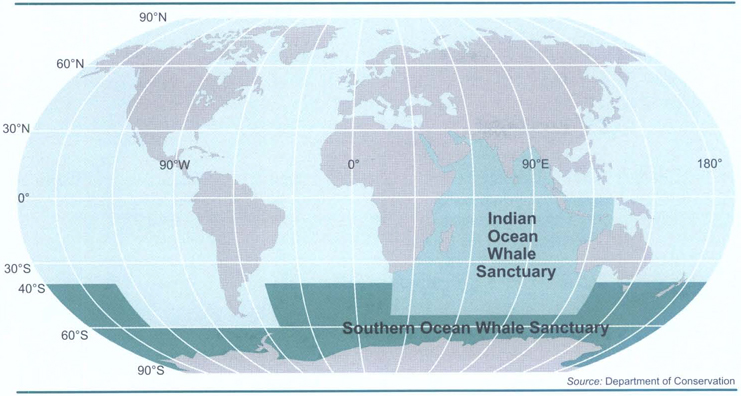

- 16.7. Whale sanctuaries

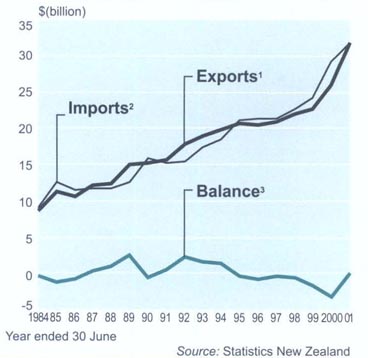

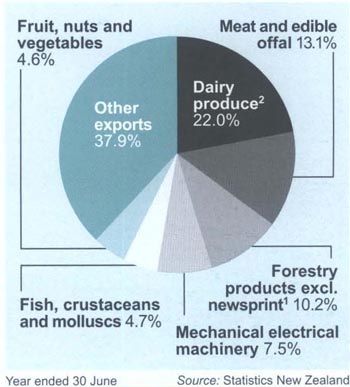

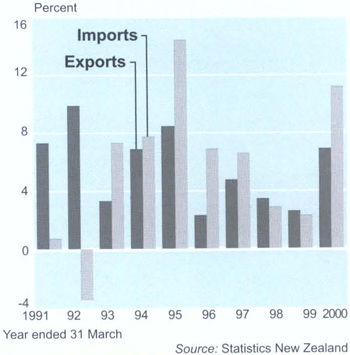

- 17.6. Imports and exports

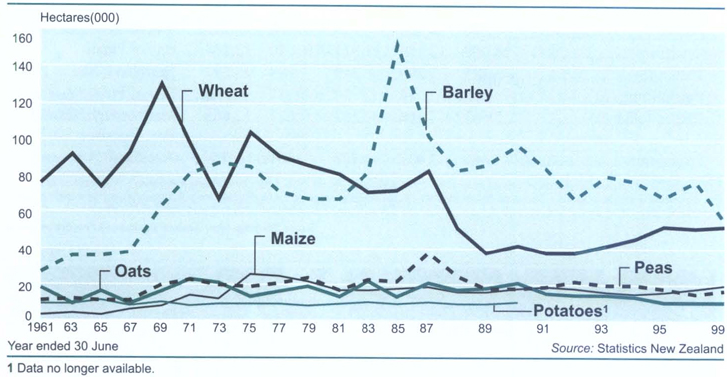

- 18.9. Major crops

Area sown

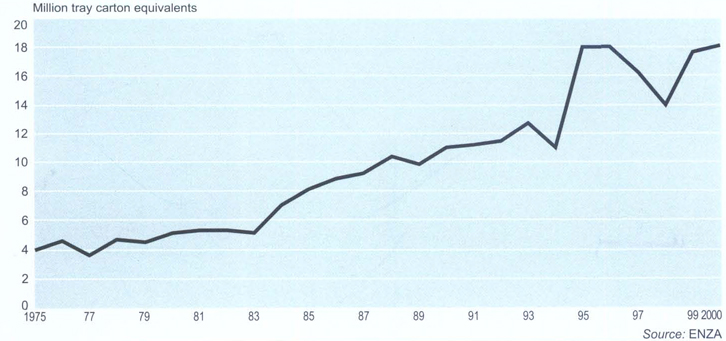

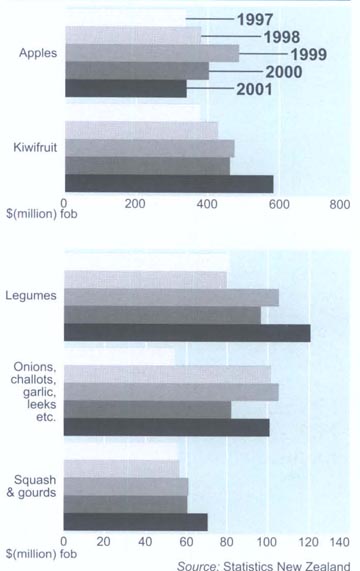

- 18.1. Pipfruit, total exports

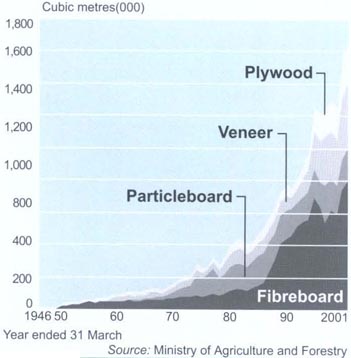

- 19.5. Wood panel production

- 19.6. Forestry exports, 2001P

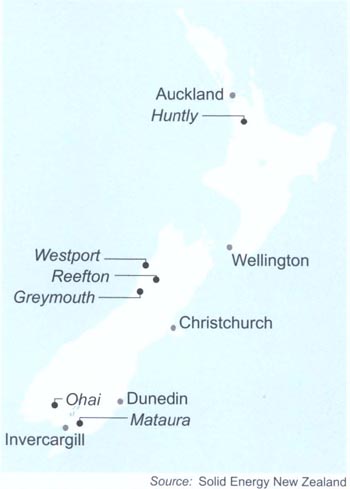

- 20.1. Coal fields, 2001

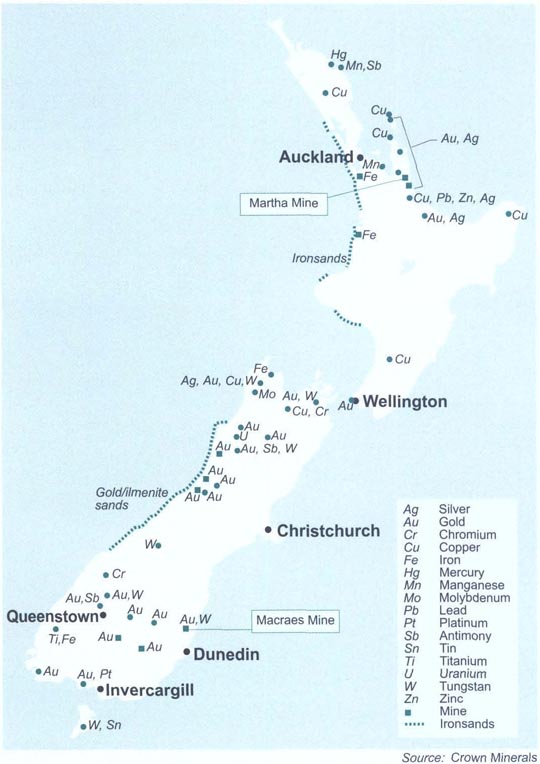

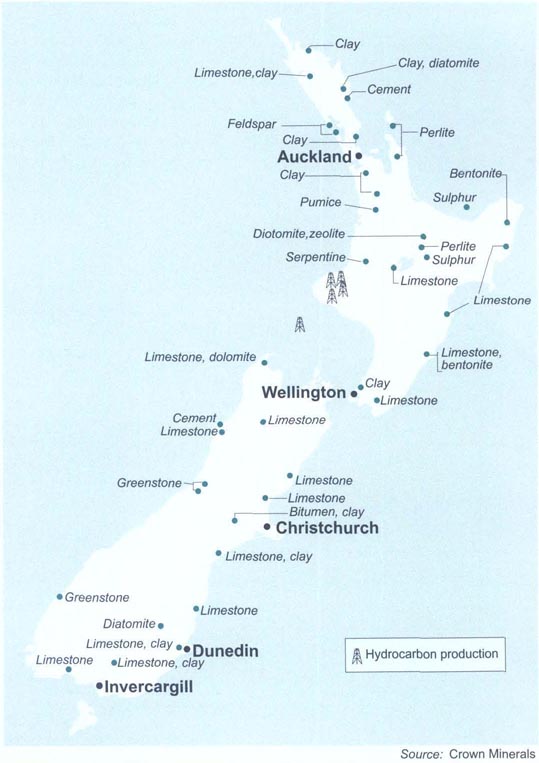

- 20.3. Non-metallic minerals

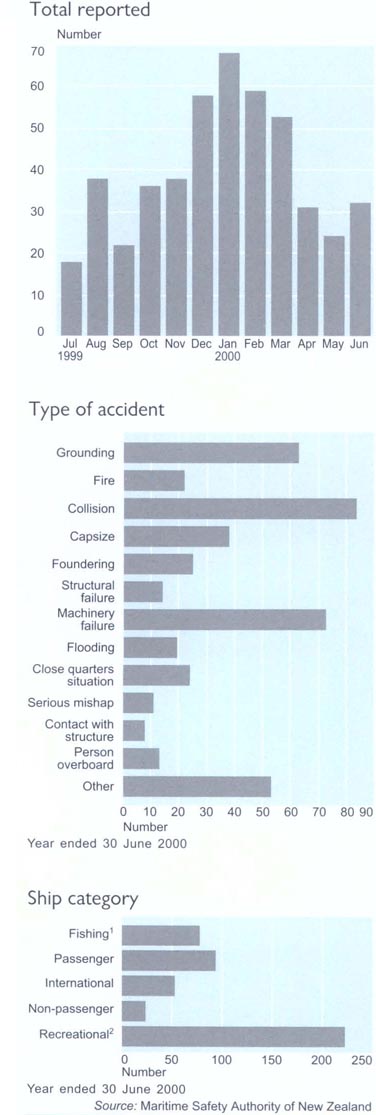

- 23.1. Marine accidents

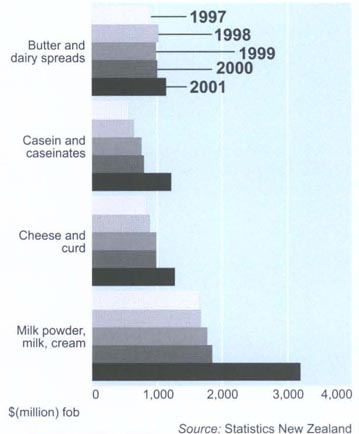

- 25.4. Forest product exports1

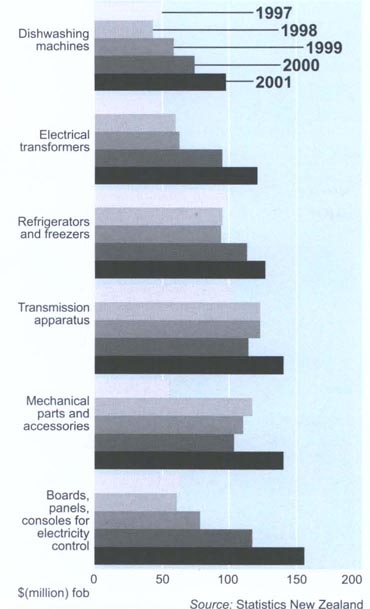

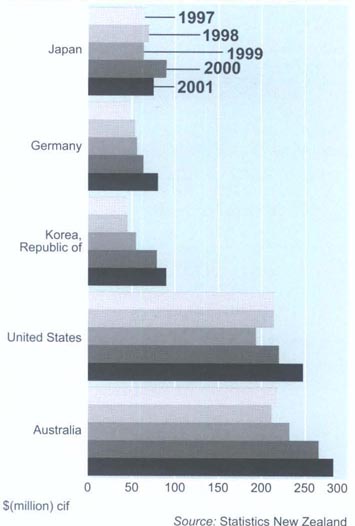

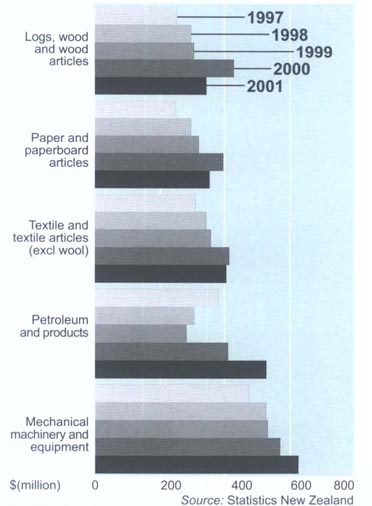

- 25.7. Machinery exports

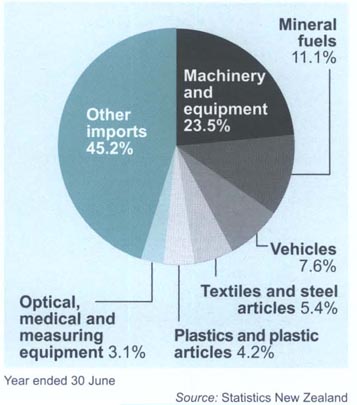

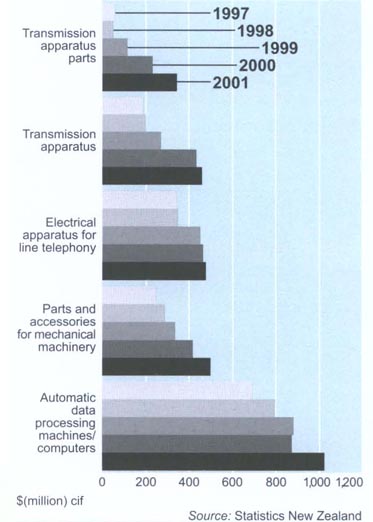

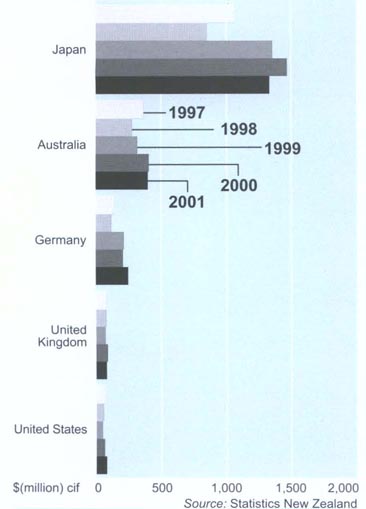

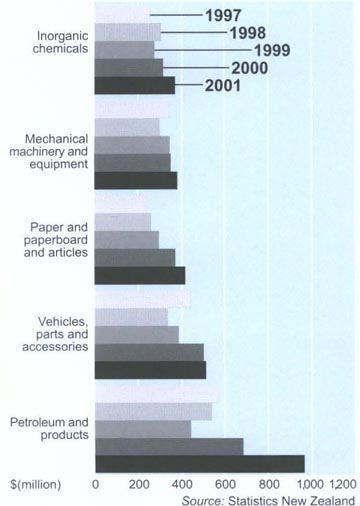

- 25.9. Machinery imports

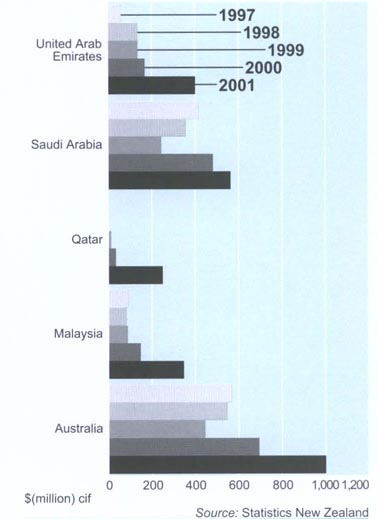

- 25.1. Mineral fuels imports

- 25.11. Vehicle imports

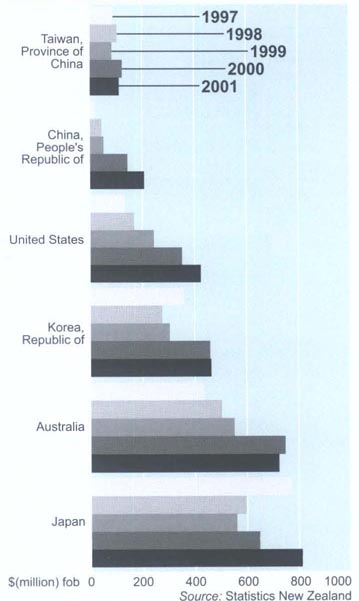

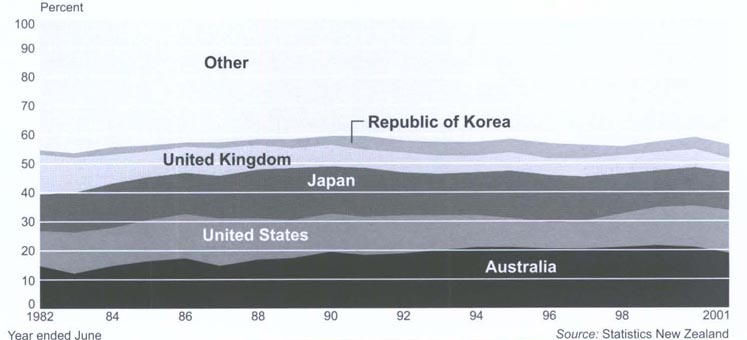

- 25.13. Major trading partners, 2001

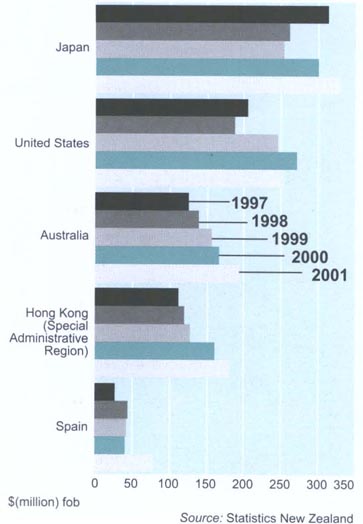

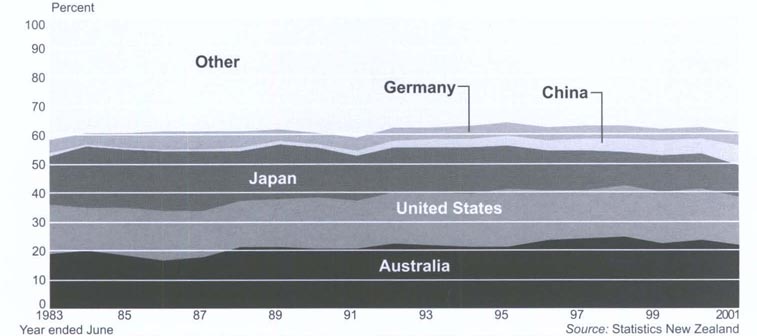

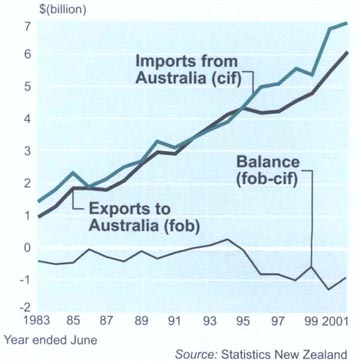

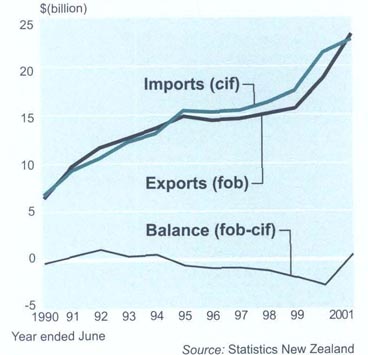

- 25.16. Trade with Australia

- 25.17. Exports to Australia (fob)

- 25.18. Imports from Australia (cif)

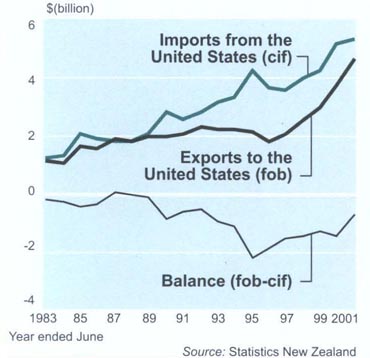

- 25.19. Trade with United States

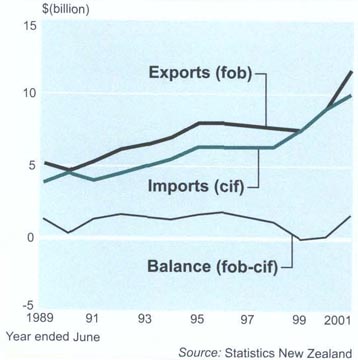

- 25.21. Trade with EU countries

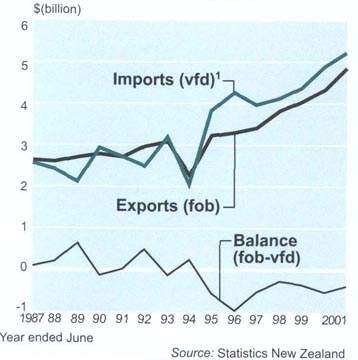

- 25.22. Trade with Asia

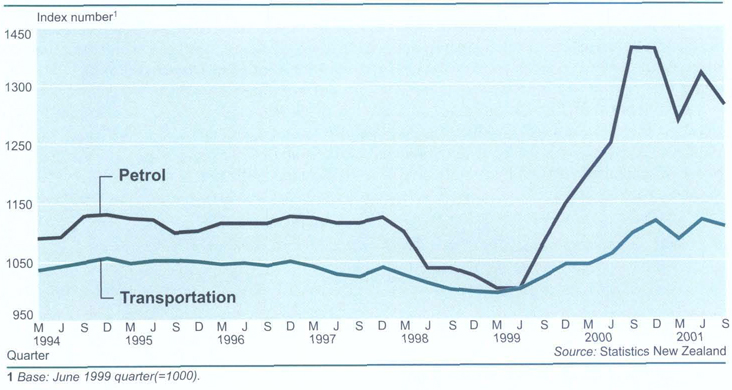

- 26.1. Transportation prices

Comparison of petrol prices with movements in transportation prices in the CPI

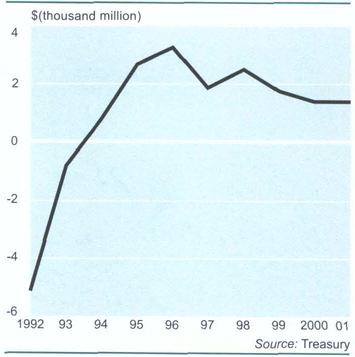

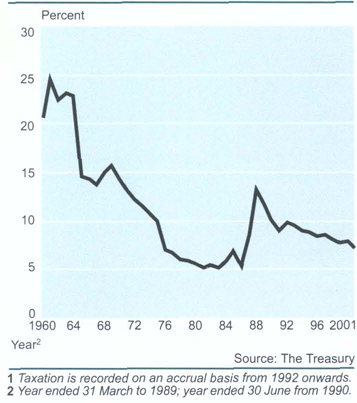

- 28.2. Operating balance

List of Tables

- 1.4. Principal mountains

- 1.5. Principal rivers(1)

- 1.6. Principal lakes(1)

- 3.18. Territorial authorities

- 3.19. Regional councils

- 4.2. Defence expenditure

- 4.5. State of the navy

- 4.6. Strength of the navy

- 4.7. State of the army

- 4.8. Strength of the army

- 5.14. Vital statistics summary

- 5.15. Death rates: summary

- 6.13. Dwelling type

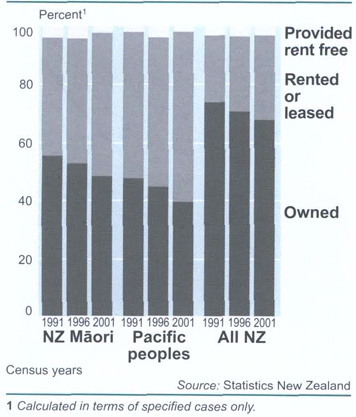

- 6.15. Tenure of household1

- 6.2. Household amenities

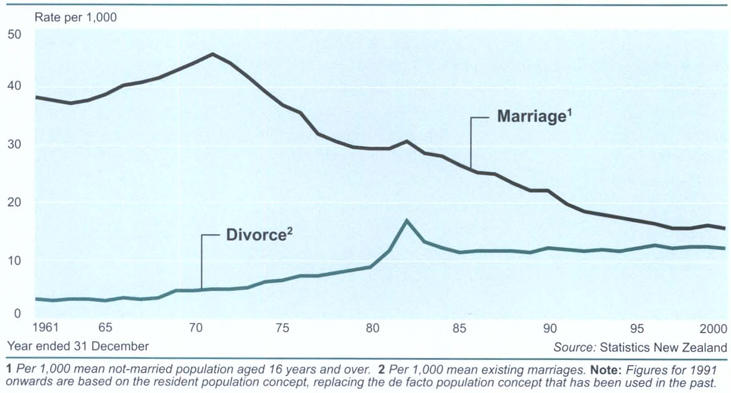

- 6.22. Marriage rates

- 6.28. Divorce rates

- 8.1. Health expenditure1

- 8.17. Drownings

- 9.4. Secondary school leavers in 2000 by level of highest attainment, gender

and ethnic identification

- 9.12. Education 1875–2000

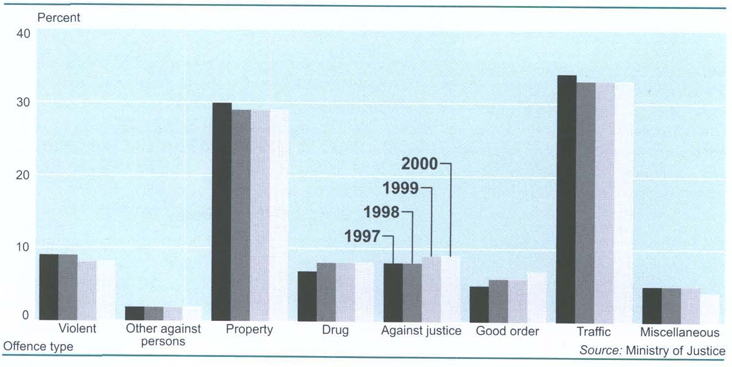

- 10.11. Sentencing for all offences1

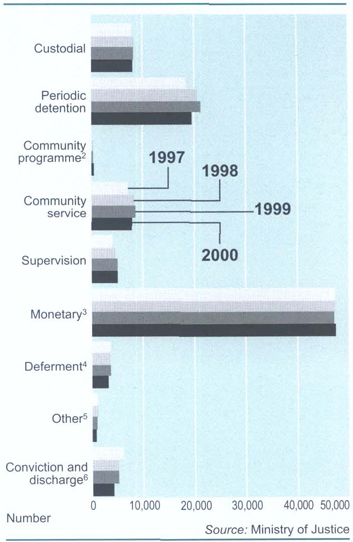

- 10.13. Community-based sentences1

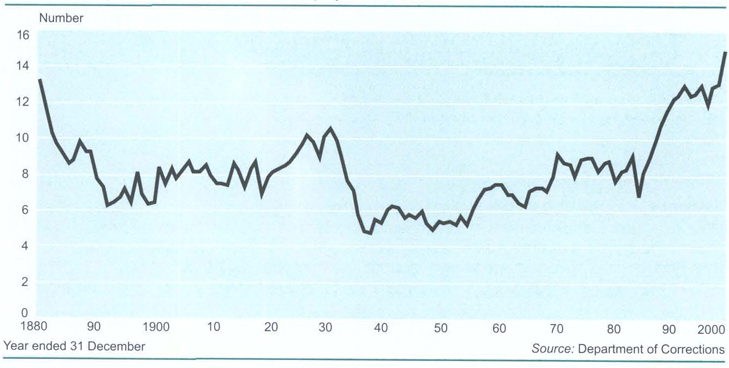

- 10.14. Penal institutions1

- 10.15. Age distribution of inmates1

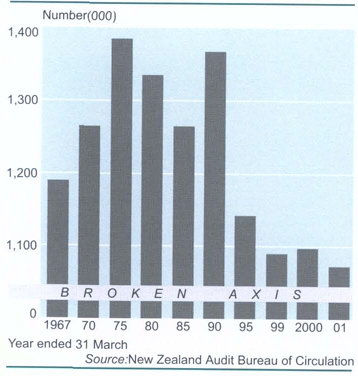

- 11.2. Magazine circulation

- 11.3. Media advertising1

- 11.5. Postal outlets

- 11.8. 2000/01 Stamp issues

- 13.1. Gaming statistics

- 14.1. Movable public holidays

- 14.21. Median income by region

- 14.24. Percentage of taxable income received and tax paid by deciles of

individuals, 1998/99 tax year

- 14.25. Labour cost index weights

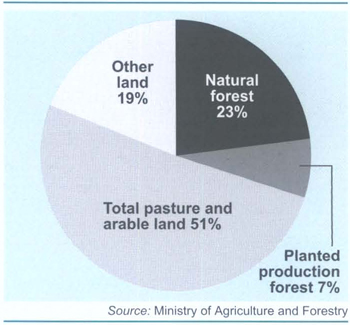

- 16.1. Land use today1

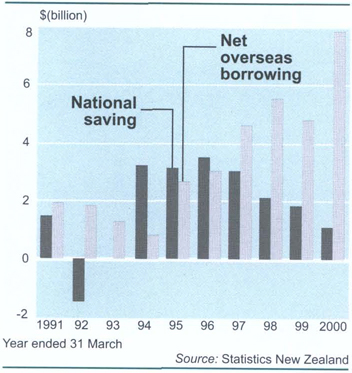

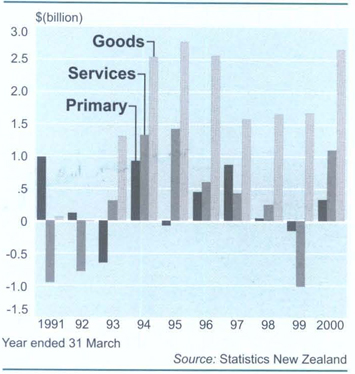

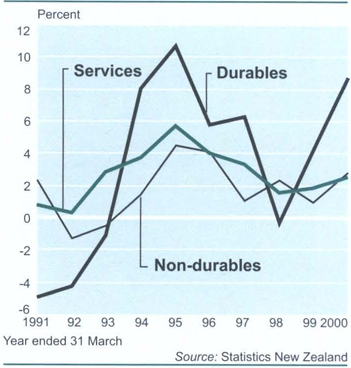

- 17.4. National capital account

- 17.5. External account

- 17.12. Capital stock

- 17.16. Trade in services1

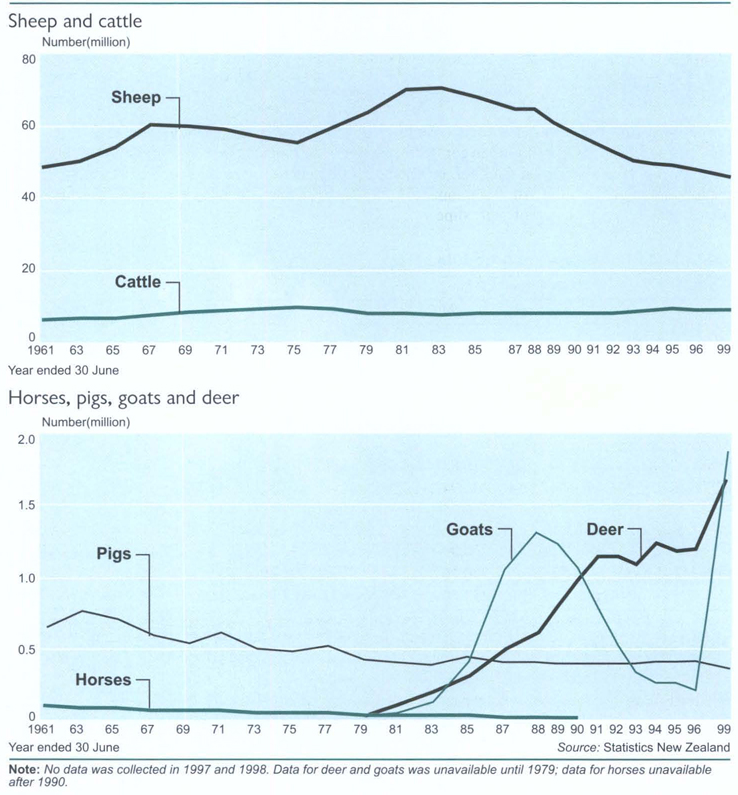

- 18.9. Sheep categories

- 18.1. Cattle categories

- 18.11. Average net schedule prices

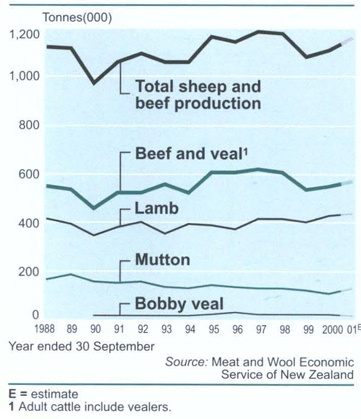

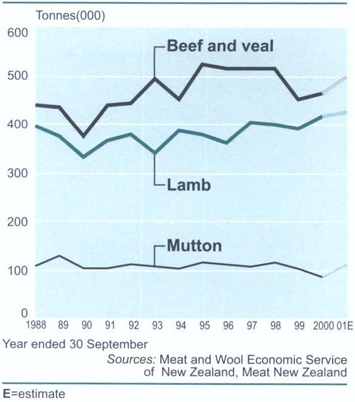

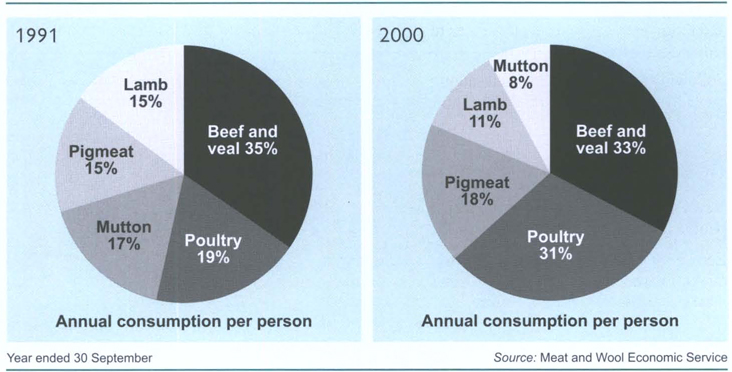

- 18.12. Meat production1

- 18.15. Export meat production

- 18.16. London wholesale lamb prices

- 18.18. Wool production1

- 18.19. Wool sold at auction

- 18.21. Wool sector export earnings1

- 18.22. Dairy factory production

- 18.25. Pigs

- 18.26. Chicken production

- 18.29. Grain and peas 19991

- 18.3. Areas planted in fruit

- 18.31. Apple and pear sales1

- 18.32. Kiwifruit production

- 18.33. Wine industry statistics

- 19.7. Volume of timber exports

- 19.8. Volume of timber imports

- 19.13. Principal fish exports

- 19.15. Seafood exports

- 20.13. Mining

- 22.1. Residential prices

- 22.2. House price

index1,2

- 22.5. Household claims

- 22.11. Work put in place

- 23.6. Formed roads and streets

- 23.11. Licensed motor vehicles

- 24.2. Company registrations

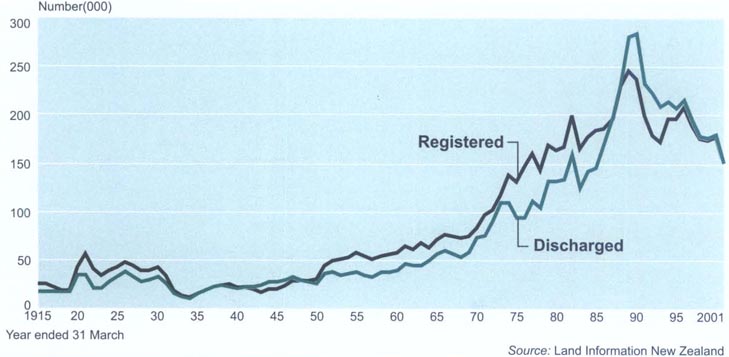

- 24.3. Personal bankruptcies

- 24.4. Company insolvencies

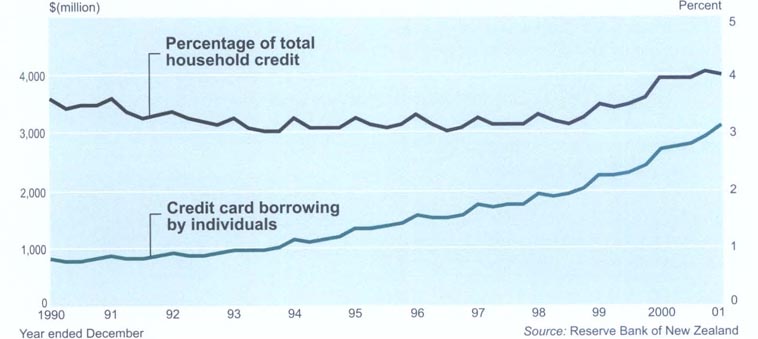

- 24.11. Value of credit card sales1

- 25.17. Mineral fuel imports1,

2, 3

- 25.24. Trade with Australia1,

2, 3

- 25.3. Trade with Japan1,

2, 3

- 26.11. Capital goods price index1

- 27.7. Foreign exchange rates1

- 28.1. Expenses

- 28.5. Breakdown of tax revenue

- 28.7. Direct taxation

- 28.8. Indirect taxation

- 28.1. Statement of borrowings

- 28.11. Type of Crown debt

Table of Contents

This 103rd edition of the New Zealand Official Yearbook continues the tradition of providing a comprehensive picture of life in New Zealand based on the most recent and accurate information available. This edition is the second Yearbook to be published formally on a two-year cycle. This longer publishing cycle allows for new kinds of analysis, and for this 2002 release has provided the opportunity for a specialist review of each chapter.

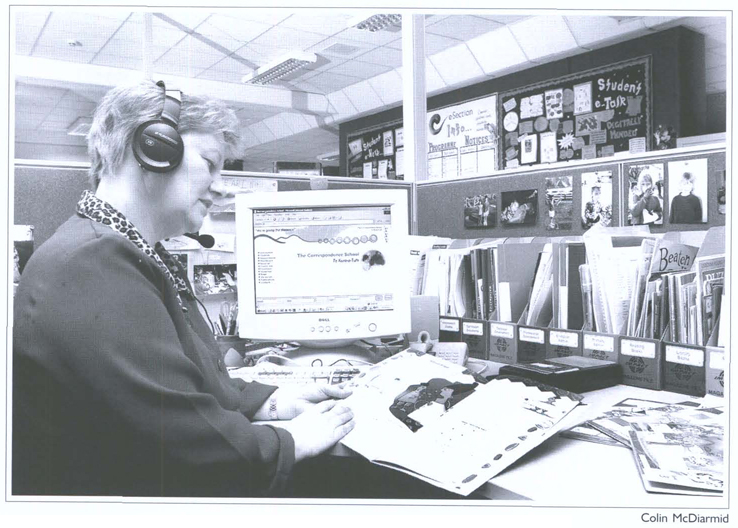

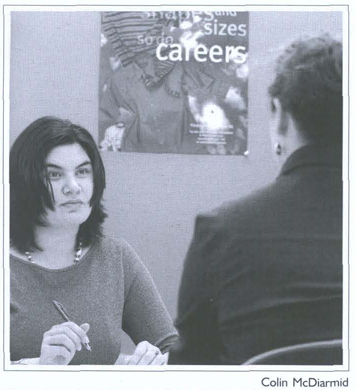

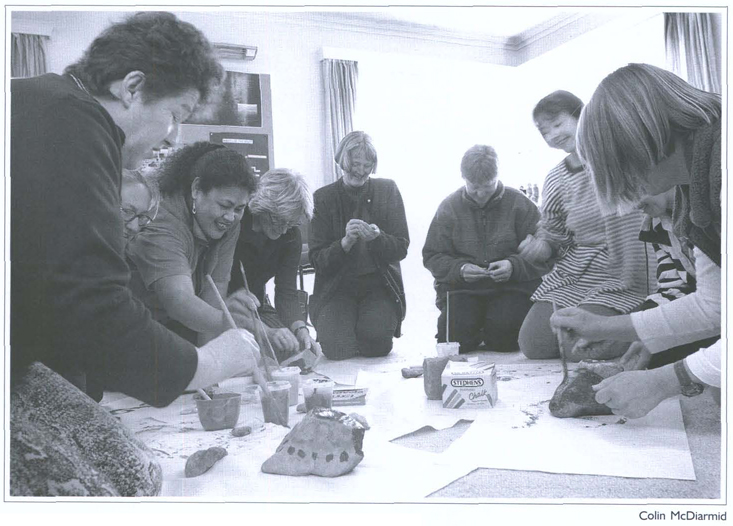

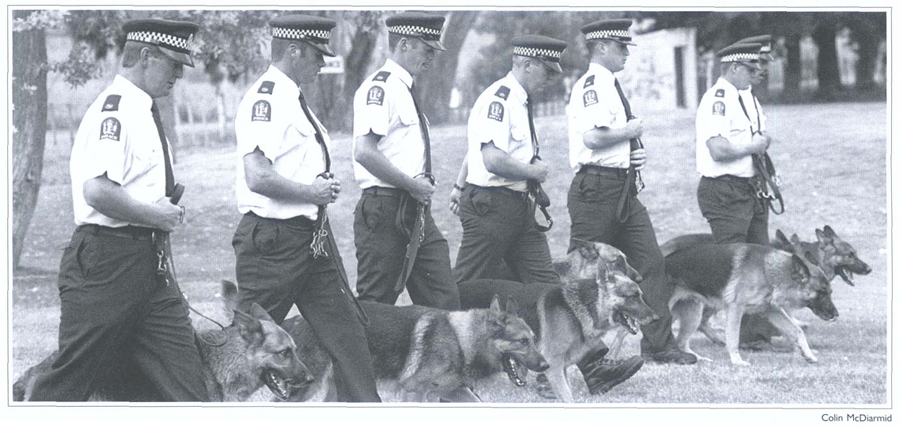

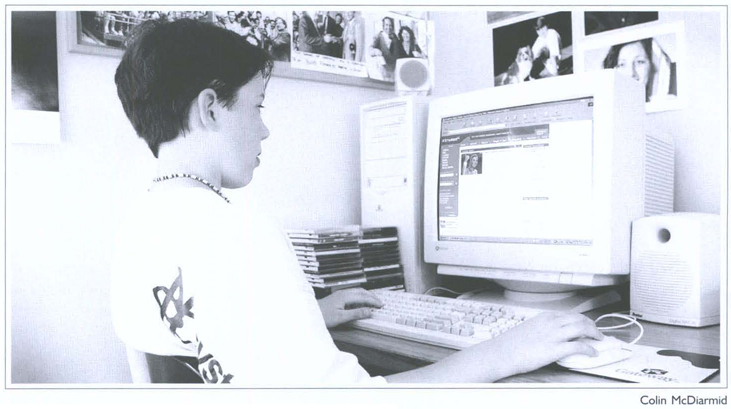

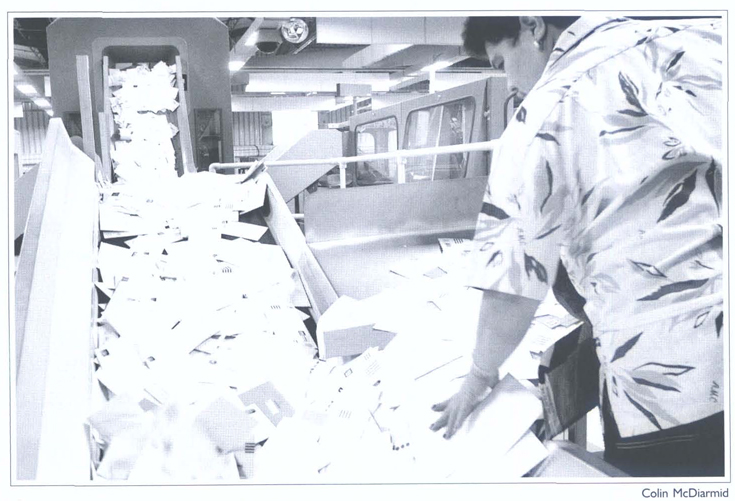

The theme for the 103rd edition is the information society, reflecting the tremendous growth and convergence of information and communications technologies in recent years. Sidebar stories and photographs illustrate the interface of technologies and people in New Zealand, highlighting changes in business, government, education, the home, culture, natural environment, sports and leisure, healthcare and other facets of daily life. Many of the historical time series graphs and tables remain, offering comparisons with the recent past as well as with previous centuries. Historian David Green's new article brings a 21st century perspective to the history of New Zealand. Preparation of this Yearbook has itself embraced information technology, with extensive use being made, for the first time, of electronic transfer of information to gather and prepare material for publication.

Information from Censuses of Population and Dwellings is always an important aspect of the Yearbook, and in this edition we are pleased to present some of the initial information produced from Census 2001. Availability of this material so soon after census day reflects the uptake and use by Statistics New Zealand of new technologies such as the electronic scanning and processing of census forms.

I would like to offer special thanks to the Yearbook team for the high standards they have achieved, and for working at a rapid pace during early 2002 to ensure Census 2001 information could be included. Our thanks also to publisher David Bateman for providing a high-quality finished product.

On behalf of Statistics New Zealand, I would also like to thank the more than 400 businesses, government departments, non-government organisations, academic institutions and individuals for their time, effort and goodwill in providing and updating contributions to the Yearbook. Finally, I again thank all New Zealanders and visitors to New Zealand who participated in Census 2001. The very high level of cooperation in not only the census but in all our other surveys ensures the continuing high quality of our official statistics.

Brian Pink

Government Statistician

The 2002 Yearbook was produced by the Information and Publishing Services Division of Statistics New Zealand, with the assistance of the many individuals and organisations listed in the ‘Contributors’ section at the end of each chapter, or below the sidebars. The department wishes to record its thanks to them and to the following:

Divisional managers: Helen Stott, Kevin Eddy

Publishing services managers: Chris Daish, Margaret O'Sullivan (acting), Geoffrey Mead, Mark McGann (acting), Angela Perkins

Yearbook Editor: Paul Cavanagh

Editor and production coordinator: Nicky McCreanor

Editorial support: Sandra Wasley, Antje Heymanns, Angela Papprill, Marie Smith

Design: Maureen Metcalfe, Merran Plunket

Typesetters: Merran Plunket, Teresa Ross, Janet Gudmun, Sandra McKenzie

Maps and diagrams: Maureen Metcalfe, Merran Plunket

Illustrations researcher: Margaret Low

Technical support: Kevin Tompson

Database design: Megan Hutchison

Database development: Irina Simeonov, Nestor Velasco

Bibliographic research: Beryl Anderson

As a new reader of the New Zealand Official Yearbook you may be surprised at the range of information within its pages. The following notes are to help familiarise you with the book.

The New Zealand Official Yearbook is published as a compendium of facts and figures on New Zealand and to describe major changes in New Zealand's administrative framework in the two years preceding publication.

The Yearbook contains the latest available statistics on particular topics. It also tells its readers where further information can be found.

There are two likely ways you will look for information.

If your question is general, for example ‘How is New Zealand governed?’, then you will probably refer firstly to the Contents (overleaf), which lists chapter headings and major sections within chapters. In approaching the book this way it is worth bearing in mind that the 28 chapters follow a ‘logical’ progression. The first few chapters describe the physical setting as well as New Zealand's history, system of government and international relations. A description of its people comes next, followed by social framework and institutions. The second section of the Yearbook begins with an overview of New Zealand's workforce and moves to a discussion of the nation in broad economic terms. Then follow descriptions of each of the constituent sectors, ending with a chapter on public sector finances.

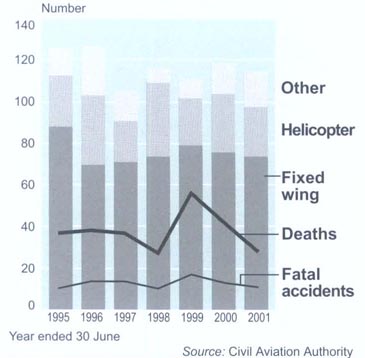

If, on the other hand, your question is more specific, for example ‘How many people died in air accidents in 2000/01?’, then the book is thoroughly indexed. A brief note on the system used can be found at the beginning of the index.

Because the Yearbook covers such a broad range of subjects, few of its statistics are being published for the first time. Many statistics from government departments and other organisations have been published in the year preceding Yearbook publication.

The source of a particular table is noted at the foot of the table. The following symbols may be used in the tables:

Figures are often rounded-off to the nearest thousand or some convenient unit. Sometimes this rounding results in tables with totals that disagree slightly with the total of the individual items shown. See sidebar on page 95 for more detail on rounding.

Statistics from Censuses of Population and Dwellings have been subject to a process of random rounding, whereby all cell values, including row and column totals, have been randomly rounded to base 3. Individual figures will therefore not necessarily add up to the stated totals.

A glossary of statistical terms used is given at the back of the book.

Statistics New Zealand has made every effort to obtain, analyse and edit the information and statistics used in the Yearbook. However, Statistics New Zealand gives no warranty that the information or data supplied contains no errors, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage caused by the use, directly or indirectly, of material contained in the Yearbook.

New Zealand's scenery, creativity and technical capability was showcased to the world in December 2001 with the release of the first of director Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings movie trilogy. To celebrate the release of The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, New Zealand Post produced a range of stamps, postcards and presentation packs featuring scenes from the movie. The six ‘Maximum Cards’ shown here feature designs derived from scenes in the film, related stamps and the date stamp commemorating the first day of issue.

Aragorn (Viggo Mortensen) with Arwen (Liv Tyler).

Balin's Tomb – the Fellowship prepares for an attack.

Gandalf the Grey

(Sir Ian

Mckellan) in Rivendell.

The patrons of the bar at the Inn

of the Prancing Pony.

Frodo Baggins (Elijah Wood) in Rivendell.

Galadriel (Cate Blanchett) before the Mirror at Lothlorien.

Ecstasy suitcase

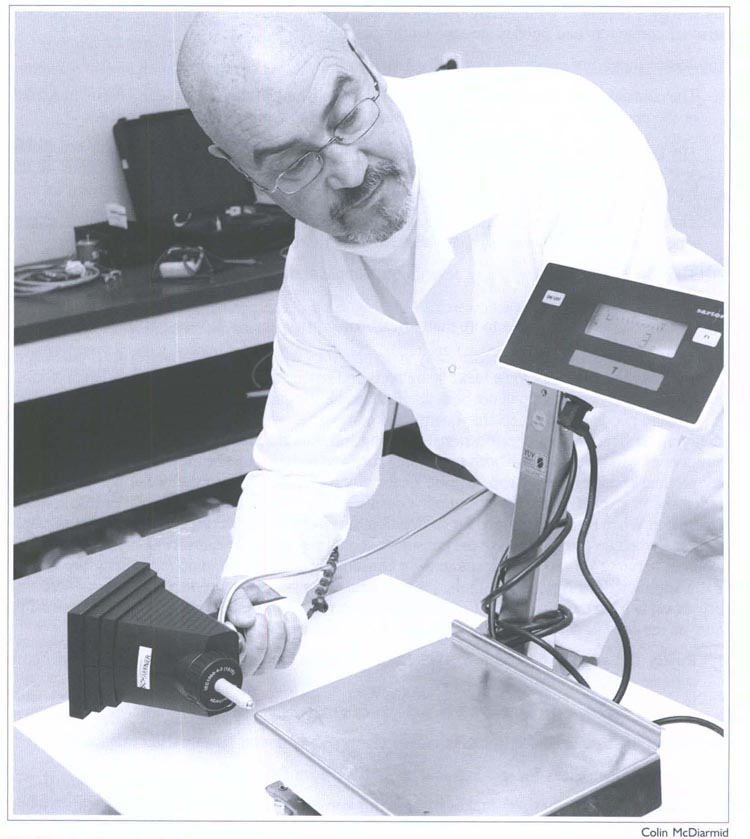

Security equipment used by the New Zealand Customs Service exposes the contents of this suitcase to customs officers – the case is full of the class B controlled drug commonly known as Ecstasy. Customs checks all passengers and crew entering New Zealand by sea or air, as well as associated craft and vessels.

Tuatara x-ray

Advances in medical technology developed for the benefit of human patients can often, with a little adaptation, benefit animal patients too. One of the more unusual clients of Wakefield Radiology in Wellington was this tuatara from Wellington Zoo, which needed an x-ray to confirm she was carrying fertile eggs. Wakefield Radiology provides the zoo with free x-ray and ultrasound services.

Fossil images

Images produced using the latest electron microscope technology clearly reveal the surface features and shape of these 0.4 to 1 million-year-old fossils. These planktic foraminifers are from a deep-sea drill-hole on the north-east slope of Chatham Rise, 1,000 kilometres east of New Zealand.

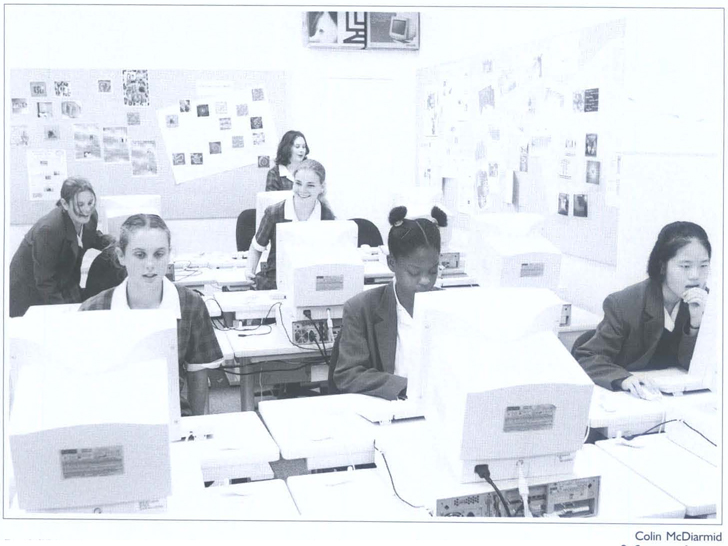

Victoria University of Wellington design students use 3D digital design software as an aid to conceptualising, generating, defining and refining complex form and space in their design solutions. Experimental model-making techniques using computer-generated data are used alongside established design studio methods to allow greater experimentation, control and manipulation of form and space to create organic, fluid designs such as those shown here.

Design issues of scale, proportion, detail, colour, reflection, refraction, opacity and tactility are addressed using advanced modeling software. Computer simulation of materials, texture and light allow the student to experiment with the visual and aesthetic qualities of the object.

Table of Contents

The mountains of New Zealand strongly influence weather systems.

New Zealand is a long, narrow, mountainous country, surrounded by a large expanse of ocean. The nearest major land mass is Australia, about 1,600km to the west. The climate of New Zealand is largely influenced by:

Its location in a latitude zone where the prevailing wind flow is westerly.

Its surrounding oceanic environment.

Its mountains, especially the main mountain chain, which modifies weather systems as they pass eastwards, and which also provide a sheltering effect on the leeward side. Local mountain formations are the cause of a number of different ‘microclimates’ in a given region.

Day-to-day weather is mostly determined by a series of anticyclones and troughs of low pressure in the westerlies. Consequently, New Zealand's weather is changeable, typically with short periods of settled or unsettled weather. At times, the westerly regime breaks down and there are cold, southerly outbreaks, with snow in winter and sometimes spring, or northerly intrusions of warm, moist air when tropical depressions move southwards into New Zealand latitudes in the summer.

The main mountain chain which extends over much of the length of the country is a major barrier to weather systems approaching from the west. Consequently, there is a marked contrast between climates of regions west and east of the mountains. This contrast is much greater than north-south climatic differences.

Surrounding oceans have a moderating effect on temperatures in most northern and western regions. However, inland and eastern areas may experience large temperature variations. High temperatures usually occur in the east in warm, north-westerly wind conditions due to the so-called föhn effect. These high temperatures are often followed by sudden falls in temperature as cold fronts move up the east coast of both islands.

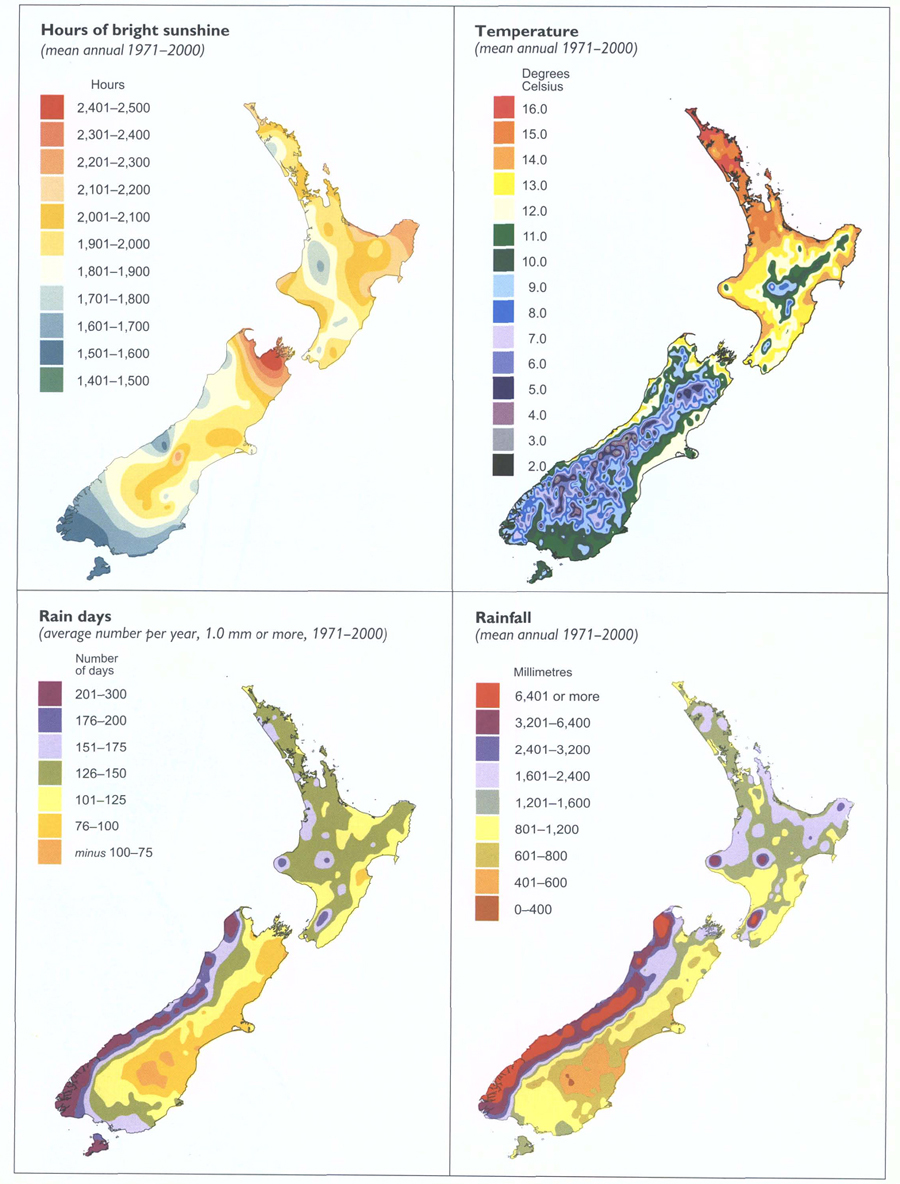

Many parts of New Zealand are subject to extremes of wind and rain, occasionally giving rise to wind damage to buildings and forests, and flooding as depressions with their fronts pass close to or over the country. The rugged terrain is an important factor in enhancement of wind strength and/or rainfall. Figure 1.1 summaries weather details from 1971 to 2000. Climate extremes up to 31 May 2001 are presented in table 1.1.

Table 1.1. Summary of New Zealand climate extremes to 31 May 2001

| Source: NIWA | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rainfall | |||

| Period | Amount mm | Location | Date |

| Highest: | |||

| 10 minutes | 34 | Tauranga | 17 April 1948 |

| 1 hour | 109 | Leigh | 30 May 2001 |

| 12 hours | 473 | Colliers Creek (Hokitika Catchment) | 22 January 1994 |

| 24 hours | 682 | Colliers Creek (Hokitika Catchment) | 21–22 January 1994 |

| 48 hours | 1,049 | Waterfall, Cropp River (Hokitika Catchment) | 12–13 December 1995 |

| 1 calendar month | 2,927 | Waterfall, Cropp River (Hokitika Catchment) | December 1995 |

| 1 calendar year | 16,617 | Waterfall, Cropp River (Hokitika Catchment) | January 1998–December 1988 |

| 365 days | 18,442 | Waterfall, Cropp River (Hokitika Catchment) | 29 October 1997–29 October 1998 |

| Lowest: | |||

| 3 months | 9 | Cape Campbell | January-March 2001 |

| 6 months | 52 | Cape Campbell | November 2000–April 2001 |

| 12 months | 167 | Alexandra | November 1963–October 1964 |

| Temperature extremes | |||

| Location | Temperature (°C) | Date | |

| Highest: | |||

| North Island | 39.2 | Ruatoria | 7 February 1973 |

| South Island | 42.4 | Rangiora and Jordan, Marlborough | 7 February 1973 |

| Lowest: | |||

| North Island | -13.6 | Chateau Tongariro | 7 July 1937 |

| South Island | -21.6 | Ophir | 3 July 1995 |

| Sunshine | |||

| Location | Total (hours) | Year | |

| Highest: | |||

| North Island | 2,588 | Napier | 1994 |

| South Island | 2,711 | Nelson | 1931 |

| Wind gusts | |||

| Location | Speed (km/h) | Date | |

| North Island | 248 | Hawkins Hill, Wellington | 6 November 1959 and 4 July 1962 |

| South Island | 250 | Mt John, Canterbury | 18 April 1970 |

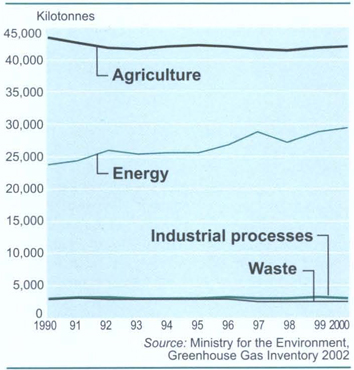

International climate change research reached a major milestone in January 2001 when the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) concluded there was now comprehensive evidence of climate change during the 20th century. Key points raised in the IPCC report were:

An increasing body of observations gave a collective picture of a warming world and other changes during the 20th century. The global average surface temperature increased by about 0.6°C. On islands east of about 160E and south of the equator, surface air temperatures increased by 0.3 to 0.8°C. Sea levels in the tropical Pacific rose by about 2mm/year.

Emissions of greenhouse gases and aerosols due to human activities continued to alter the atmosphere in ways that were expected to affect the climate, and would continue to change atmospheric composition throughout the 21st century.

There was new and stronger evidence that most of the warming observed during the past 50 years was attributable to human activities (emissions of greenhouse gases and aerosols), and that anthropogenic (human-induced) climate change would persist for many centuries.

Confidence in the ability of models to project future climate has increased.

Global average temperature and sea levels were projected to rise under all IPCC greenhouse gas emission scenarios. Projected increases in global mean temperatures from 1990 to 2100 for a range of plausible emission scenarios lie between 1.4 and 5.8°C. Global mean sea level changes lie between 9 and 88cm.

Changes were expected in some extreme weather and climate events, including higher maximum temperatures and more hot days, more heavy rainfall events, and, in some areas, an increase in peak wind intensities and rainfall intensities in tropical cyclones. Projections showed little change, or a small increase, in amplitude for El Nino events during the next 100 years. However, even with little or no change in El Nino amplitude, global warming was likely to lead to greater extremes of drying, heavy rainfall and to increased risks of droughts and floods that occur with El Nino events in many different regions.

What the warming climate will mean in detail for the South Pacific is still the subject of investigation by scientific researchers, with key emerging issues being changes in rainfall patterns and associated shifts in water resources and agricultural growing conditions. Impact scenario studies will provide an important link between global climate dynamics and the ability of New Zealand and South Pacific communities to adapt to local changes that will affect everyday lives.

A hoarfrost in Alexandra, Central Otago, during the winter of 2001.

Following is a summary of knowledge gained in the past decade about the effect of climate change on New Zealand.

Projected climate changes. Temperatures in New Zealand are likely to increase faster in the North Island than in the South Island, but generally less than global average temperatures. Rainfall is projected to increase in the west of the country and to decrease in many eastern regions. In the long term, rising seas are expected to increase erosion of vulnerable beaches and breach coastal protection structures more often.

Agriculture. The agricultural sector could benefit under climate change, but also faces risks. The key benefit to agriculture is likely to be from increased carbon dioxide concentrations, which could lead to greatly increased growth rates and water-use efficiency. In addition, warmer conditions and lengthened growing seasons could allow the long-term southward shift of climate-limited activities, and new crops and related industries could be introduced. The most significant risks include more droughts and floods in some areas, particularly in the east of New Zealand. Warmer temperatures could also make the growing of some current fruit crops in some northern areas uneconomical.

Native ecosystems. Climate change may add to pressure on ecosystems already under threat. Fragmented native forests of drier lowland environments in Northland, Waikato and Manawatu, and in the east from East Cape to Southland, are probably the most vulnerable to climate change.

Urban environment, transport and energy. The main threat to the urban environment comes from possible increases in heavy rainfall, which would put pressure on drainage and stormwater systems and increase the risk of flooding in some areas. Warmer conditions will substantially reduce home heating costs, leading to reduced electricity demand during the peak winter season, but possibly increased demand for air conditioning during summer.

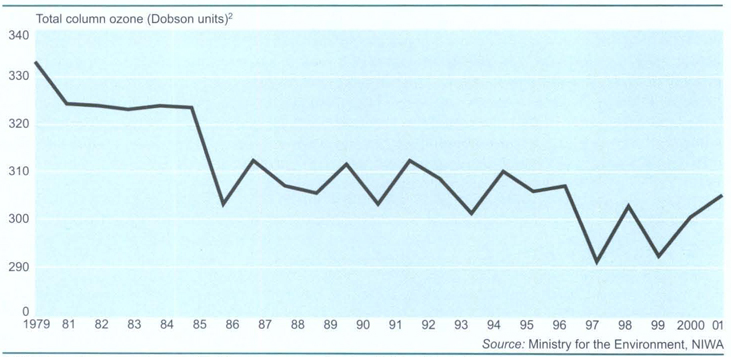

Health. Higher temperatures are expected to reduce winter illnesses, but could lead to higher death rates during summer. A warmer climate could also allow the spread of mosquitoes capable of transmitting diseases such as Ross River virus and dengue fever. Recent research has also found that climate change could lead to a delay in the recovery of the ozone layer. This would increase the period during which New Zealanders are exposed to high levels of ultraviolet radiation, which is known to lead to skin cancers. However, the possible effects of greenhouse gases on the ozone layer are still highly uncertain.

Pacific neighbours. New Zealand has close links with many Pacific Island countries. Many of these countries are highly vulnerable to rising sea levels caused by climate change. As a result, New Zealand may face increased demand for development aid and disaster relief.

Table 1.2 gives predicted changes to temperature and rainfall.

Table 1.2. Predicted changes in annual mean temperature (°C) and precipitation (%) between 1970–1999 and 2070–2099, based on averages from four global climate models

| Region | Temperature | Precipitation |

|---|---|---|

| Source: MORST | ||

| Northland, Auckland | +1.0° to +2.8°C | -10% to 0% |

| Western North Island from Waikato to Wellington | +0.8° to +2.7°C | 0% to +20% |

| Eastern North Island from Bay of Plenty to Wairarapa | +0.9° to +2.7°C | -20% to 0% |

| Nelson, Marlborough, to coastal Canterbury and Otago | +0.8° to +2.5°C | -20% to +5% |

| West Coast and Canterbury foothills | +0.6° to +2.5°C | +5% to +25% |

| Southland and inland Otago | +0.6° to +2.2°C | 0% to +30% |

2001. New Zealand climate records continued to tumble in 2001, both for average and extreme temperatures. The year was one of the driest on record in many eastern South Island areas, as well as parts of Wellington, in spite of a wet October-December period.

The North Island bore the brunt of 11 rainfall/flooding extremes, while tornadoes also featured in 2001, with at least eight reported, along with an unusual number of high wind events, many of which caused property damage.

The year featured many new climate records and extremes, with five unusually warm months, and two much colder than average. There were six cold snaps in winter, four with snow and two with extreme frosts. There were at least two widespread and damaging hailstorms, with hailstones ‘the size of golf balls’.

Higher than average pressures occurred from the south Tasman Sea across the lower South Island and east past the Chatham Islands. Pressures were below average in the north Tasman Sea and to the north. This pattern resulted in more frequent easterlies and north-easterlies over the north of the North Island and more settled conditions elsewhere.

Analyses of month-by-month records for 2001 compared with recorded statistics for previous years show:

The year's national average temperature was 12.8°C (0.3°C above the 1961–1990 normal).

The highest annual mean temperature recorded for the year was 16.9°C at Cape Reinga.

The highest recorded extreme temperature for the year was 35.3°C at Timaru airport on 4 February and the lowest was −12.2°C at Hanmer forest on the morning of 5 July.

May, August, September, October and December were unusually warm months, January was rather cool and July was the coldest for more than 30 years.

December was unusually wet, with record low sunshine over the North Island.

The driest recorded centre was Alexandra, with only 299mm of rain for the year.

North Egmont was the wettest location with 7,546mm. Traditionally wet Milford Sound managed only 5,134mm.

Christchurch was the driest main centre with 405mm and Auckland the wettest with 1,256mm. Wellington received 1,053mm and Dunedin 515mm.

The capital was again the sunniest of the three largest centres, with 2,094 sunshine hours, followed by Christchurch (2,072 hours), and Auckland (1,981 hours). Nelson was the sunniest centre in 2001 with 2,550 hours, followed by Blenheim with 2,484 hours and Motueka with 2,430 hours.

2000. The year 2000 produced a wide variety of climate extremes and the second warmest winter since records began in the mid 1850s. Unusually high sunshine hours occurred in Taranaki. A drought in summer and early autumn contrasted with 15 high rainfall events producing floods in most other months. Two notable heatwaves occurred, and six cold snaps, five with snow. Three tornadoes were reported, and 11 high wind events all caused property damage. Severe hailstorms occurred on three separate occasions. More anticyclones than normal occurred east of New Zealand, resulting in more easterlies over the north of the North Island, and north-westerlies over the far south.

National average temperature for the year 2000 was 12.7°C (0.2°C above the 1961–1990 normal).

The highest recorded annual mean temperature for the year was 16°C at Whangarei.

The highest extreme temperature for the year was 35°C at both Darfield and Culverden on 4 March, and the lowest −12.4°C at Tekapo on the morning of 24 August.

The winter was the second warmest on record since reliable measurements were established in the 1850s. The national average winter temperature of 9.1°C was up 0.9°C on the 1961–1990 normal.

The driest recorded centre was Alexandra, with only 475mm of rain for the year.

The wettest recorded location was Milford Sound, with an annual total of 7,019mm.

Christchurch was the driest main centre with 706mm and Auckland the wettest with 1,130mm. Wellington received 994mm and Dunedin 926mm.

The capital was the sunniest of the three largest centres with 2,172 sunshine hours, followed by Christchurch (2,141 hours), and Auckland (1,962 hours).

Nelson was the sunniest centre in 2000 with 2,534 hours, followed by Blenheim with 2,435 hours and Tauranga with 2,347 hours.

New Plymouth's 2,334 hours of sunshine was the highest in the area since 1943.

Climate extremes. NIWA's annual climate summaries (available on its website www.niwa.cri.nz) contain detailed descriptions of extreme weather events for the year. These include extremes of temperatures and sunshine hours, and notable occurrences of snowfalls and frosts, droughts, floods and high rainfall, tornadoes, gales and high winds, and severe hailstorms.

New Zealand lies in the south-west Pacific Ocean and comprises two main and a number of smaller islands. Their combined area of 270,500 square kilometres is similar in size to Japan or the British Isles. See table 1.3 for more details.

Table 1.3. Land area of New Zealand(1)

| Land area | Size (sq km) |

|---|---|

1Includes all internal waterways (lakes and rivers). 2Includes all offshore islands 20 sq km or larger, except those listed separately. Source: Land Information New Zealand | |

| North Island | 113,729 |

| South Island | 150,437 |

| Offshore islands(2) | 1,065 |

| Stewart Island/Rakiura | 1,680 |

| Chatham Islands | 963 |

| Raoul Island | 34 |

| Campbell Island/Motu Ihupuku | 113 |

The main North and South Islands are separated by Cook Strait, which, at its narrowest point, is 20km wide. The North and South Islands lie on an axis running from north-east to south-west, except for the low-lying Northland peninsula.

The administrative boundaries of New Zealand extend from 33° to 53° south latitude, and from 160° east to 173° west longitude.

In addition to the main and nearby islands, New Zealand also includes the small inhabited outlying islands of the Chathams, 850km east of Christchurch; Raoul Island, in the Kermadec Group 930km north-east of the Bay of Islands; and Campbell Island, 590km south of Stewart Island. New Zealand also has jurisdiction over the territories of Tokelau and the Ross Dependency (see Chapter 4).

New Zealand is more than 1,600km long and 450km wide at its widest part, and has a long coastline for its area. The coast is very indented in places, providing many natural harbours.

The country is also very mountainous (see table 1.4), with less than a quarter of the land less than 200m above sea level. In the North Island, the main ranges run generally north-east to south-west, parallel to the coast, from East Cape to Cook Strait, with further ranges and four volcanic peaks to the north-west. The South Island is much more mountainous than the North Island. A massive mountain chain, the Southern Alps, runs almost the length of the island. There are many outlying ranges to the Southern Alps in the north and the south-west of the South Island. There are at least 223 named peaks higher than 2,300m.

Table 1.4. Principal mountains

| Mountain or peak | Elevation |

|---|---|

1Taranaki or Egmont is the correct format for the dual name as prescribed in the 1986 Gazette 2The height of Aoraki/Mt Cook was confirmed by Dr John Beavan, from the Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences, as 3,754m – this was determined photogrametrically after the 1991 slip from the peak. Source: Land Information New Zealand | |

| metres | |

| North Island: | |

| Ruapehu | 2,797 |

| Taranaki or Egmont(1) | 2,518 |

| Ngauruhoe | 2,287 |

| Tongariro | 1,967 |

| South Island: | |

| Aoraki/Mt Cook(2) | 3,754 |

| Tasman | 3,497 |

| Dampier | 3,440 |

| Silberhorn | 3,300 |

| Hicks (St David's Dome) | 3,198 |

| Lendenfeldt | 3,194 |

| Torres | 3,163 |

| Teichelmann | 3,160 |

| Sefton | 3,157 |

| Malte Brun | 3,155 |

| Haast | 3,138 |

| Elie de Beaumont | 3,117 |

| Douglas | 3,085 |

| La Perouse | 3,079 |

| Heidinger | 3,066 |

| Minarets | 3,055 |

| Aspiring/Tititea | 3,033 |

| Glacier Peak | 3,007 |

There are also 360 glaciers in the Southern Alps. The largest are, on the east, the Tasman (29km in length), Murchison (13km), Mueller (13km), Godley (13km) and the Hooker (11km), and, on the west, the Fox (15km) and the Franz Josef (13km).

New Zealand's rivers (see table 1.5) are mainly swift and difficult to navigate. They are important as sources of hydroelectric power and artificial lakes have been created as part of major hydroelectric schemes. Table 1.6 describes the largest lakes.

Table 1.5. Principal rivers(1)

| River | Length |

|---|---|

1More than 150km in length from the mouth to the farthest point in the river system irrespective of name, including estimated courses through lakes. Source: Land Information New Zealand | |

| km | |

| North Island: | |

| Flowing into the Pacific Ocean – | |

| Rangitaiki | 193 |

| Waihou | 175 |

| Mohaka | 172 |

| Ngaruroro | 154 |

| Flowing into the Tasman Sea – | |

| Waikato | 425 |

| Whanganui | 290 |

| Rangitikei | 241 |

| Manawatu | 182 |

| Whangaehu | 161 |

| Mokau | 158 |

| South Island: | |

| Flowing into Cook Strait – | |

| Wairau | 169 |

| Flowing into the Pacific Ocean – | |

| Clutha/Matau | 322 |

| Taieri | 288 |

| Clarence | 209 |

| Waitaki | 209 |

| Waiau | 169 |

| Waimakariri | 161 |

| Flowing into Foveaux Strait – | |

| Mataura | 240 |

| Waiau | 217 |

| Oreti | 203 |

| Flowing into the Tasman Sea – | |

| Buller | 177 |

Table 1.6. Principal lakes(1)

| Lake | Maximum depth | Area |

|---|---|---|

1More than 20 square kilometres in area. Source: Land Information New Zealand and NIWA | ||

| m | sq km | |

| North Island: | ||

| Taupo | 163 | 606 |

| Rotorua | 45 | 80 |

| Wairarapa | 3 | 80 |

| Waikaremoana | 248 | 541 |

| Tarawera | 87 | 36 |

| Rotoiti | 94 | 34 |

| South Island: | ||

| Te Anau | 417 | 352 |

| Wakatipu | 380 | 293 |

| Wanaka | 311 | 193 |

| Ellesmere | 2 | 181 |

| Pukaki | 99 | 169 |

| Manapouri | 444 | 142 |

| Hawea | 384 | 141 |

| Tekapo | 120 | 88 |

| Benmore (artificial) | 120 | 75 |

| Hauroko | 462 | 7 |

| Ohau | 129 | 61 |

| Poteriteri | uncharted | 47 |

| Brunner | 109 | 39 |

| Coleridge | 200 | 36 |

| Monowai | 161 | 31 |

| Aviemore (artificial) | 62 | 29 |

| Dunstan (artificial) | 70 | 27 |

| Rotoroa | 152 | 23 |

| Mahinerangi (artificial) | 31 | 21 |

New Zealand is in an area of the world characterised by active volcanoes and frequent earthquakes. The ‘ring of fire’, as this area is known, forms a belt that surrounds the Pacific Ocean and is the surface expression of a series of boundaries between the plates that make up the earth's crust. The boundary between the Indo-Australian plate and the Pacific plate runs through New Zealand, and the processes from their collisions have had a profound effect on New Zealand's size, shape and geology.

The oldest rocks in New Zealand are found in Nelson, Westland and Fiordland. They have been dated back to the Paleozoic era about 570 million years ago. Nearly three-quarters of New Zealand is covered by sedimentary rocks, created by the interplay of earth movement and erosion. The most common forms of sedimentary rocks in New Zealand are sandstone, mudstone, greywacke, conglomerate and limestone. As well as sedimentary rocks of various ages, New Zealand incorporates in its complex structure metamorphic rocks (schist, gneiss and marble) and intrusive igneous rocks (granite, gabbro, diorite and serpentine). Volcanic rocks (basalt, andesite, rhyolite and ignimbrite) are products of the many volcanic eruptions that have characterised New Zealand's geological history.

Soil is a product of its environment. Its composition depends on the parent ingredient, the climate, the length of time it has weathered, topography and the vegetation under which it has formed. The complex soil pattern of New Zealand (see table 1.7) is a result of many different kinds of rock and the various conditions under which the soils have formed. Climate varies from such extremes as sub-tropical North Auckland to the cold uplands of the alpine regions and the semi-arid basins of Central Otago. The country's topography is equally varied, with 50 percent of the land classifiable as steep, 20 percent as moderately hilly and only 30 percent as rolling or flat. Natural vegetation ranges from kauri forest to sub-alpine scrub, and from tussock grassland to broadleaf forest. Occasionally, occurrences such as river floods on alluvial plains, sand drifts, or volcanic ash eruptions interrupt and alter the pattern of soil development.

Evidence of episodes of intense mountain building between one million and six million years ago are apparent in the New Zealand landscape of today. Mountain chains were pushed up during this period and there was movement and displacement of the earth's crust along faults. Due to this activity, well-preserved tilted fault blocks bounded by fault scarps (steep faces hundreds or even thousands of metres high) are visible in the landscape of some regions. Fault movements continue to the present day and have accompanied several major earthquakes of the past century.

A caver descends into Harwood Hole near Takaka in the Golden Bay district.

Erosion has transformed the landscape during this time, carving detailed patterns of peaks, ridges, valleys and gorges. The deposition of debris has built up alluvial plains, shingle fans and other construction forms. At the coast, waves have eaten back headlands and built beaches, spits and bars. Glaciers carved the fiords of Fiordland and valleys occupied by most of the South Island lakes. Sea level changes accompanied formation, and later melting, of global glacial ice. These changes affected the erosion and deposition of rivers and were responsible for the formation of many prominent river terraces.

Volcanic activity during the past few million years played an important part in shaping the landscape. The largest volcanic outpourings of late geological times were in the region between Tongariro National Park and the Bay of Plenty coast. The most recognisable volancoes in New Zealand now occur in the North Island, where a number are still active. They include Ruapehu, Tongariro, Ngauruhoe, White Island and Mt Tarawera. Others such as Mt Taranaki or Egmont and Rangitoto may be considered dormant at present, although they are still regarded as significant hazards.

Living in New Zealand means living with earthquakes. There is an almost continuous belt of earthquake activity around the edge of the Pacific Ocean that affects the geological stability of many countries on the Pacific Rim, particularly New Zealand, west coast United States, Chile, Peru, Japan and the Philippines. New Zealand's level of activity is similar to that of California, but slightly lower than that of Japan. A magnitude 8 earthquake occurs in New Zealand about once a century, a magnitude 7 quake averages out at once a decade and there is an average rate of one magnitude 6 quake a year.

Sheep graze in the gentle rolling country of Southland.

Table 1.7. Classification of New Zealand soils

| Region | Soils | Vegetation and land use |

|---|---|---|

| Source: Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences | ||

| North Auckland Peninsula and Auckland region | Large areas of infertile gumland soils formerly covered with kauri; granular, oxide and ultic soils from volcanic rocks and weathered sandstone. | Patchy land use. Exotic forests on lowland country and remnant kauri forest on uplands. Intensive dairying on rolling lands around Kaipara Harbour, Whangarei, Kaikohe and Dargaville. Sheep and beef on hill country. |

| Bay of Plenty-Waikato-Thames-Hauraki Plains | Volcanic ash covers much of the area, giving rise to deep, granular soils with good physical properties. Peaty and gley soils with high ground water on Hauraki Plains and parts of Waikato Basin. | Predominantly pastoral farming (mostly dairying), exotic forestry and several large tracts of indigenous forest. Kiwifruit along coastal Bay of Plenty. Scattered maize cropping. |

| Volcanic Plateau | Pumice soils, lacking in some essential trace elements, but mostly deep, friable and highly suited to tree growth. | Important watershed with large areas protected as native forest. Extensive exotic forests. Topdressing of former scrub areas with trace elements has allowed widespread farming. |

| East Coast-Wairarapa | Brown soils. Significant areas of recent alluvial soils on Gisborne and Heretaunga Plains. Pallic soils on rolling land south of Hawke's Bay. | Semi-extensive sheep farming (wool and store sheep) on dry hill country. Intensive lamb production on flat to rolling plains. Market gardens and orchards near Gisborne, Napier, and Hastings. Important pip-fruit production. Vineyards. Pockets of dairying close to main ranges from Norsewood south. |

| Taranaki | Volcanic ring plain consists of allophanic soils, usually from deep volcanic ash, but stony in west. Soft-rock uplands in east Taranaki. | Distinct contrast between intensive dairying on ring plain, and severely eroded inland hill country, with many steep ridges covered in second-growth forest or dense gorse. |

| Manawatu-Horowhenua | Sand dunes and swampy hollows common along coast. Loess-covered terraces and river flats inland. Pallic soils on drier terraces with sand soils near coast and organic and recent alluvial soils on lower plains. | Intensive sheep production and cropping on the terrace country; semi-intensive sheep and beef in hill country of Rangitikei. Exotic forestry on coastal sand country. |

| Marlborough Sounds-Nelson | Pockets of fertile, recent alluvial soils on Waimea and Motueka Plains. Large areas of steepland soils and stony soils on Moutere Gravels. | Intensive orcharding and market gardens. Exotic forests in Marlborough Sounds and Moutere Gravels. |

| Marlborough-Kaikoura Coast | Pallic soils and brown soils with pockets of recent alluvial soils. | Intensive sheep farming and cropping on river terraces, semi-intensive sheep and beef on hill country. Vineyards in lower Wairau Valley. |

| West Coast | Extensive gleyed podzols and organic soils, with recent soils on alluvial flats. | Indigenous forestry declining; national parks and reserves; exotic forestry on hill country of north Westland. Dairying on river flats. |

| Canterbury | Very thick layer of gravel covered by variable thicknesses of fine material. Pallic soils and associated stony soils. | Intensive cropping for cereals and fodder crops. Intensive sheep production, with widespread irrigation of pasture. |

| Otago | High-country brown soils on ranges, pallic soils at intermediate altitudes and semi-arid soils (often stony), in basins. | Extensive sheep and beef farming in uplands. Intensive orcharding in Central Otago basins, especially for stonefruit; irrigation necessary. Market gardening in lower Taieri. |

| Southland | Southland Plain mainly deposits of gravel and silt. Brown soils and recent alluvial soils. Pallic soils inland in drier areas. | Semi-intensive sheep and beef farming in rolling areas inland, and intensive fattening on plains. Dairying on plains near Invercargill. |

New Zealand has many earthquakes because it straddles the boundary between two of the earth's great tectonic plates – the Pacific Plate in the east and the Australian Plate in the west. These two plates are converging obliquely at about 30mm/year in Fiordland, increasing to about 50mm/year at East Cape. The plates converge in different ways. In the North Island and the northern South Island, the Pacific Plate sinks below the Australian Plate. Earthquakes originating within the subducting Pacific Plate are less than 30km deep along the eastern coast, and become deeper westward. In Fiordland and the region to the south, the Australian Plate subducts beneath the Pacific Plate, so the earthquake sources are shallow in the west and deeper in the east under Fiordland.

Between these two subduction zones, the crust of both plates is too buoyant to subduct, so the convergence is accommodated by uplift, which created the Southern Alps, and horizontal movement along the Alpine Fault. This results in parts of Nelson and western Otago, adjacent five million years ago, now being 450km apart. The forces driving this sideways and upward movement create shallow earthquakes.

About two-thirds of New Zealand's earthquakes are deep, while shallow earthquakes originate within the earth's crust, which has an average thickness of 35km in New Zealand. Crustal quakes are responsible for almost all damage to property, and are widely scattered throughout New Zealand. In the Taupo volcanic zone, from White Island to Ruapehu, swarms of small earthquakes of similar magnitude are associated with the area's active volcanism. Although the number of shocks is alarming, they rarely cause damage.

Earthquake risk. The worst disaster that can reasonably be expected within a generation is a 7.5 magnitude earthquake on the segment of the Wellington fault within the city. It has a 12 percent probability of occurring within the next 30 years, and would affect 200,000 residential properties from Palmerston North to Nelson, as well as roads, bridges and dams, and services such as electricity, water and sewerage.

The Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences (GNS) in Lower Hutt runs the National Seismograph Network. A major upgrade to the equipment that monitors earthquakes and volcanoes in New Zealand was started in 2001. The Earthquake Commission is providing $5 million a year over 10 years to install upgraded equipment at new sites and replace existing equipment to more rapidly and reliably determine the location and magnitude of all significant earthquakes within the New Zealand region (see sidebar). Such information is rapidly broadcast to civil defence and emergency management authorities and international earthquake centres in the United Kingdom and the United States. New Zealand scientists also undertake a large body of research aimed at improving understanding of, and ways to mitigate, seismic hazard in New Zealand. Mitigation measures include improved engineering design of buildings and infrastructure, better prepared communities and better regional planning.

Principal earthquakes in New Zealand in 2001. New Zealand was hit by at least six potentially damaging earthquakes in 2001, but they were either too distant from population centres or too deep to cause harm.

In what GNS seismologists described as an average year in terms of size, number and distribution of earthquakes, the largest jolt was a magnitude 7.0 earthquake on August 21 centred offshore in the Kermadec Trench, 420km north-east of Gisborne. Although distant, its large size and relatively shallow depth meant it was felt throughout much of the North Island and as far south as Christchurch. It caused minor damage and a brief electricity blackout at Tolaga Bay, 56km north-east of Gisborne.

Also of note was a magnitude 6.2 earthquake centred 20km north of Taumarunui on May 24. It was felt throughout the eastern North Island, but its impact was not severe because of its depth of 260km.

A magnitude 6.1 earthquake on the morning of December 8 located 30km south-west of Haast, and shallower than 12km, was felt throughout the southern South Island, but was away from major population centres.

All of these larger earthquakes were followed by dozens of smaller aftershocks. In the case of the quake south-west of Haast, aftershocks occurred at the rate of up to 20 an hour during the first two days after the main shock. Accurate recordings of aftershocks give seismologists valuable information about the nature of the main shock and its relation to the geology of the area. In particular, aftershocks can indicate how the main shock may have increased or decreased the stress on neighbouring faults.

Only about 1 percent of the 16,000 earthquakes recorded in New Zealand each year are big enough or shallow enough to be felt by humans. As a general guide, shallow earthquakes above magnitude 5.0 are capable of causing damage and casualties in built-up areas.

During late September and early October 2001, a number of moderate-sized shallow earthquakes occurred in southern Hawke's Bay, off the coast at Porangahau. The largest of these, a magnitude 5.6 quake on September 24, was felt widely throughout the central and southern North Island.

Among other moderate-sized shallow earthquakes recorded in 2001 was a magnitude 5.0 event on April 4, 30km south-east of Blenheim. The largest of a cluster of eight earthquakes that occurred in that area on that day, it was felt throughout Marlborough, the Wellington region and as far north as Wanganui. On May 18, a magnitude 5.1 earthquake 50km west of Methven in Canterbury was felt on the West Coast and in inland Canterbury.

A number of moderate-sized deep earthquakes also occurred during 2001. On October 15, a magnitude 5.8 quake with an epicentre close to Hastings was felt widely. A magnitude 5.0 quake on October 24, 30km north-west of Taupo, was felt along the east coast of the North Island. On November 9, a magnitude 5.3 earthquake 30km south of Nelson was felt in the northern South Island and in the Wellington region. Finally, a magnitude 5.0 event on December 8, located 30km south-west of Gisborne, was felt in the East Cape and Hawke's Bay regions. There were also three earthquakes above magnitude 5.0 in the Bay of Plenty during the first half of the year, but all these events were too deep to cause damage.

The New Zealand region is characterised by both a high density of active volcanoes and a high frequency of eruptions. Volcanic activity in New Zealand occurs within the North Island and offshore to the north-east in the Kermadec Islands. In the past 150 years, volcanoes have killed more people than earthquakes, yet the scale and style of historically recorded volcanic activity is dwarfed by events known to have occurred in the past 2,000 to 5,000 years.

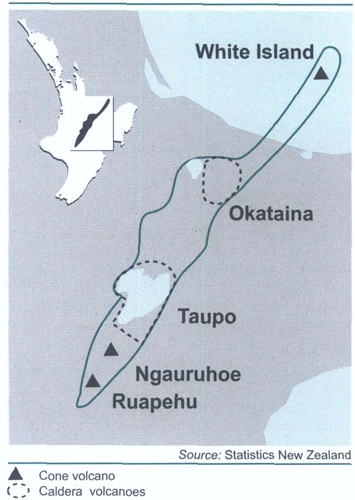

Volcanism. New Zealand volcanism is confined to five areas in the North Island – the Bay of Islands, Whangarei, Auckland, White Island to Ruapehu, and Taranaki or Egmont. The area from White Island to Ruapehu is known as the Taupo volcanic zone and is by far the most frequently active. There are three major types of volcano in New Zealand:

Volcanic fields such as Auckland, where each eruption builds a single small volcano (eg Mt Eden), which does not erupt again. The next eruption in the field occurs at a different place, the site of which cannot be predicted until the eruption is imminent.

Cone volcanoes such as Taranaki or Egmont and Ruapehu, where a succession of small eruptions occurs from roughly the same point on the earth's surface. The products of successive eruptions accumulate close to the vent to form a large cone, which is the volcano itself. The site of future eruptions can generally be predicted.

Caldera volcanoes, such as Taupo and Okataina (Tarawera). Eruptions at these volcanoes are occasionally so large that the ground surface collapses into the ‘hole’ left behind. For example, Lake Taupo infills a caldera formed in two episodes about 1,800 and 26,000 years ago.

The Taupo volcanic zone (see Figure 1.3) contains three frequently active cone volcanoes (Ruapehu, Ngauruhoe and White Island) and the two most productive caldera volcanoes (Taupo and Okataina) in the world.

Casualties. Deaths due directly or indirectly to volcanism (and associated hydrothermal explosions) represent the biggest single source of fatalities from natural disasters in New Zealand since 1846 (see table 1.8). Economic loss due to volcanism, however, has been low compared with that from earthquakes or flooding. The cost of the 1995 and 1996 eruptions of Ruapehu has been estimated at $130 million. However, an assessment of the size and style of volcanic eruptions in the geologically recent past, coupled with consideration of the economic development of New Zealand, especially in the central North Island, shows that the record since 1846 represents only a fraction of the type and size of hazard posed by New Zealand volcanism.

Table 1.8. Deaths in volcanic areas since 1846

| Year | Location (eruption) | Cause – hazard | Fatalities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source: Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences | |||

| 1846 | Waihi (Lake Taupo) | Debris avalanche/mudflow from thermal area | c 60 |

| 1886 | Tarawera Rift | Large volcanic eruption | 108 |

| 1903 | Waimangu (Tarawera) | Hydrothermal explosion | 4 |

| 1910 | Waihi (Lake Taupo) | Debris avalanche/mudflow from thermal area | 1 |

| 1914 | White Island | Debris avalanche from crater wall | 11 |

| 1917 | Waimangu (Tarawera) | Hydrothermal explosion | 2 |

| 1953 | Tangiwai (Ruapehu) | Lahar and flood from crater lake | 151 |

| >337 | |||

Crises. The term volcanic crisis is used to describe the entire time period associated with a major volcanic eruption. It includes precursors, the eruption and its aftermath. During all this time, people and property are at risk.

The onset of a volcanic crisis is often predictable, but the exact course of an eruption is not. Large volcanic eruptions are predictable because precursors like earthquakes, ground deformation and increased outputs of volcanic gas can be used to infer that an eruption is imminent, so enabling some site-specific planning or mitigation. Large volcanic eruptions are preceded by a period of days to years of high levels of seismicity, ground movements and changes to hot springs and gas vents. However, once an eruption has started, significant hazards can be present for much longer periods than with any other natural event. The eruption may be followed by months to decades of flooding, erosion and land instability.

A feature of volcanic crises compared with other kinds of natural hazards is that each eruption has a far wider range of possible outcomes, each, in turn, with a characteristic range of threats to life and property.

Major types of volcanic hazard are ash and pumice fall, ash and pumice currents, lavas, lahars/flooding and gases/acid rain. Volcanism on a relatively minor scale (eg Ruapehu 1945, 1995, 1996) causes disruption and damage on a regional scale, while some larger events (eg Taupo 1,800 years ago) adversely affect the entire national economy.

Mt Ruapehu eruptions in 1995 and 1996 resulted in extensive ash falls throughout the North Island.

For each volcano, a hazard map of different potential eruptions can be drawn. Each map has a number of zones specific to a particular hazard (eg lahar, ash fall). The risk varies considerably depending on factors such as topography, wind direction at the time of the eruption, and the position of communities and infrastructure with respect to the erupting volcano. At all of New Zealand's volcanoes, with the possible exception of Ngauruhoe, the historic record is inadequate to assess the full range of activity. Therefore, to help assess the return intervals of any specific kind of eruption, studies are made of deposits left by prehistoric eruptions and interpretations are made of the size and style of each event, together with an estimation of the age. Such information is available to various extents for all of New Zealand's volcanoes. The probability of a future eruption from a wholly new site, or of a type of activity not represented in the past history of the volcano, is remote.

Surveillance. Volcanologists use three primary techniques to establish the ‘health’ of an active volcano:

Monitoring of volcanic earthquakes. This is done using closely-spaced networks of seismometers. These networks are designed to detect movement of magma (molten rock) below the surface and allow assessment of the possible onset and timing of eruptive activity. There are five volcano-seismic networks in New Zealand (Auckland, Bay of Plenty-Rotorua, Taranaki, Tongariro and Taupo).

Monitoring of ground deformation. This is done using precise geodetic surveys. The concept is that if magma is moving upwards before an eruption, it will cause the volcano to swell (ie the ground surface to rise), and this swelling can be detected. A novel version of this technique uses lakes at Taupo and Okataina as giant spirit levels.

Monitoring of volcanic gases. Magma at depth in the earth contains gases (carbon dioxide, together with various compounds of sulphur, chlorine and fluorine) dissolved in it. As the magma rises to shallow levels before an eruption, these gases are released and come to the surface via fumaroles. The temperatures and the abundance of the gases and their relative proportions give information on the state of the magma and how close to the surface it is.

In a volcanic crisis, practical steps can be taken to mitigate risk and lessen the threat to life, but this requires accurate perception of the onset of a crisis. This perception in turn depends on a knowledge of the ‘background’ or ‘normal’ levels of seismicity, ground movement and gas flux at the volcano, coupled with ‘real-time’ determination of any significant changes from this background. New Zealand has an active volcano surveillance programme to define these background levels.

Mitigation. Experiences at recent large volcanic eruptions like Rabaul (Papua New Guinea) and Pinatubo (Philippines) show it is possible to minimise loss of life during volcanic crises. On the other hand, Nevado del Ruiz and El Chichon showed that poor planning results in major loss of life. A major feature of mitigation is public education. An informed, knowledgeable population makes intelligent decisions, and ‘self-evacuation’ was a key feature at Rabaul and Pinatubo.

The principal tool to accomplish this in New Zealand is the Yellow Book series of the Ministry of Civil Defence and Emergency Management. Communities exposed to frequent volcanic hazards evolve simple measures to limit risk. One example is Whakapapa village, Mt Ruapehu, where posters and brochures give detailed precautions against lahar hazards on ski-fields.

The islands of New Zealand separated from their nearest neighbours more than 80 million years ago. Some of the original inhabitants endured times of turbulent change and violent upheaval, evolving and adapting to become part of a unique natural biota (or region). Other species died out (either nationally or regionally), unable to compete or survive environmental disturbances such as ice ages. For example, coconut palms were once found in New Zealand, and kauri, now confined to the north of the North Island, used to grow as far south as Canterbury. Over the years, the earliest inhabitants were joined by other plants and animals carried across the oceans by wind and current.

The pre-human community was notable for the absence of snakes, land mammals (apart from three species of bat) and many of the flowering plant families.

Whole orders and families were found only in New Zealand, including tuatara, moa and kiwi, all of the native lizards, and nearly 200 species of native earthworms. Many remarkable plants, insects and birds evolved to fill ecological niches normally occupied by mammals. Others diversified to fill new territories created by sea-level fluctuations and land uplift. With no mammalian predators on the ground, but avian predators everywhere, flightlessness was not a handicap, nor was size. Moa (11 species, some up to 3m tall) became extinct in pre-European times, but many other large flightless birds still remain, including kiwi, the nocturnal kākāpō (the only flightless parrot in the world) and weka (of the rail family).

Flightless insects are numerous, including many large beetles and 70 or so species of the cricketlike weta, found only in New Zealand.

New Zealand, with 84 species, has the most diverse seabird fauna of any country. Nearly half of all native bird species depend on the ocean for food, the feeding zones of some extending as far south as the Antarctic continent. New Zealand's extensive coastline and many islands offer a huge range of habitat, from estuary and mud-flat, to rocky cliffs and boulder bank.

The ocean itself is marvellously rich. There are about 400 different marine fish in the waters around New Zealand, as well as various species of seals, dolphins and porpoises. Twenty-nine species of whale have been recorded, and three of the largest (sperm, humpback and right) regularly migrate to New Zealand waters in spring and autumn.

The most widespread and complex type of forest in New Zealand is a podocarp (conifer) broadleaf association. It is generally found at lower altitudes and is characterised by a variety of species, a stratified canopy and an abundance of vines and epiphytic plants. Beech and kauri forests, by contrast, are much simpler in structure. New Zealand's beech species have close relatives in Australia and South America and the five different types of species in New Zealand have exploited habitats from valley floor to mountain tops. Kauri, true forest giants, dominate only in the warmer climes to the north.

Some of the most specialised plants are those occupying the alpine zone. A remarkable 25 percent of all New Zealand's plants can be found above the treeline. Ninety-three percent of all alpine plants are found only in New Zealand, compared with 80 percent for the rest of the higher plant species. Snow tussock herbfields are one of the most distinctive elements in this cold, windswept environment. Remarkably long-lived, some larger specimens may be several centuries old. Like beech trees, they seed infrequently, but in profusion.

A definitive feature of New Zealand's land-based plants and animals is their degree of specialisation and narrow habitat requirements (eg takahē/tussock grasslands; blue duck/fast flowing rivers and streams) and their evolution in the absence of mammalian predators (birds) or browsers (plants). This specialisation, and the adaptations which make New Zealand's wildlife so unique, render them extremely vulnerable to introduced predators, such as rats and cats; competitors, such as deer and possums; and loss of habitat.

The arrival of people in New Zealand heralded times of rapid change. Introduction (intentionally or accidentally) of exotic plants and animals, and the modification of habitat, radically affected native species populations. In the pre-1800 period, following the arrival and expansion of Māori, forest cover was reduced and 34 species became extinct, including moa, the adzebill and the flightless goose. In the much shorter post-1800 period of European settlement, the forest area was further reduced to around 25 percent of the land, nine more birds became extinct and many more were threatened. Since 1840, more than 80 new species of mammals, birds and fish, and more than 1,800 plant species have been introduced, in many places totally changing the landscape and ecology.

One uniform time is kept throughout mainland New Zealand. This time is 12 hours ahead of Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) and is called New Zealand Standard Time (NZST). It is an atomic standard maintained by the Measurement Standards Laboratory, part of Industrial Research Ltd, Lower Hutt. One hour of daylight saving, called New Zealand Daylight Time (NZDT), which is 13 hours ahead of UTC, is observed from 2am (NZST) on the first Sunday in October, until 2am (NZST) on the third Sunday in March. Time kept in the Chatham Islands is 45 minutes ahead of that kept in New Zealand.

1.1 Dr Jim Salinger (NIWA); Ministry for the Environment; Ministry of Science, Research and Technology.

1.2 Land Information New Zealand; National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research Ltd (NIWA); New Zealand Speleological Society.

1.3 Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Ltd.

1.4 Department of Conservation.

1.5 Industrial Research Ltd.

Statistics New Zealand divisional manager responsible: Zane Colville.

Trotter M, and McCulloch B (1996). Digging up the Past: New Zealand's archaeological history, rev edition, Penguin, Auckland.

Climate Change Impacts on New Zealand (2001). Ministry for the Environment, Wellington.

Sturman A, and Tapper N (1996). The Weather and Climate of Australia and New Zealand, Oxford University Press, Auckland.

The National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research Ltd (NIWA) operates an extensive climatological database and publishes the Monthly Climate Digest, as well as regional climatologies, maps and other publications.

McKinnon M (ed) (1997). Bateman New Zealand Historical Atlas: Ko Papatūānuku e takoto nei, Bateman, in association with historical branch, Department of Internal Affairs, Auckland.

Wards I (1976). New Zealand Atlas, Government Printer, Wellington.

Terralink International Ltd publishes topographical maps of New Zealand.

Aitken JJ, and Lowry MA (1995). More Earthquakes Explained, Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences, Wellington.

Aitken JJ (1996). Plate Tectonics for Curious Kiwis, Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences, Wellington.

Brazier R, Keyes I, and Stevens G (1990). The Great New Zealand Fossil Book: Pictures of ancient life in an evolving land, Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences, Wellington.

Forsyth PJ, and Aitken JJ (1995). New Zealand Minerals and Rocks for Beginners, Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences, Wellington.

Gregory J (1988). Ruamoko's Heritage: Volcanoes of New Zealand (video and kit), Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences, Wellington.

Hayward, BW (1996). Precious Land: Protecting New Zealand's landforms and geological features, Geological Society of New Zealand, Lower Hutt.

Hicks G, and Campbell H (eds) (1998). Awesome Forces: The natural hazards that threaten New Zealand, Te Papa Press in association with the Earthquake Commission and the Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences, Wellington.

Thompson B, Brathwaite B, and Christie T (1995). Mineral Wealth of New Zealand, Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences, Wellington.

The Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences publishes geological and geophysical maps covering all New Zealand, plus bulletins, reports, guidebooks and handbooks.

Bishop N, and Gaskin C (1992). Natural History of New Zealand, Hodder and Stoughton, Auckland.

Dawson J (1988). Forest Vines to Snow Tussocks: The story of New Zealand plants, Victoria University Press, Wellington.

Heather BD, and Robertson HA (1996). The Field Guide to the Birds of New Zealand, Viking, Auckland.

King CM (1984). Immigrant Killers: Introduced predators and the conservation of birds in New Zealand, Oxford University Press, Auckland.

Meads M (1990). Forgotten Fauna, Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, Wellington.

Molloy L, and Cubitt G (1994). Wild New Zealand, New Holland, London.

Salmon JT (1998). The Native Trees of New Zealand, 2 vol, Reed, Auckland.

Salmon JT (1992). A Field Guide to the Alpine Plants of New Zealand, 3rd edition, Godwit,

www.doc.govt.nz – Department of Conservation

www.gns.cri.nz – Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Ltd

www.linz.govt.nz – Land Information New Zealand

www.weather.co.nz – Metservice

www.niwa.cri.nz – National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research Ltd

www.terralinkinternational.com – Terralink International Ltd

Table of Contents

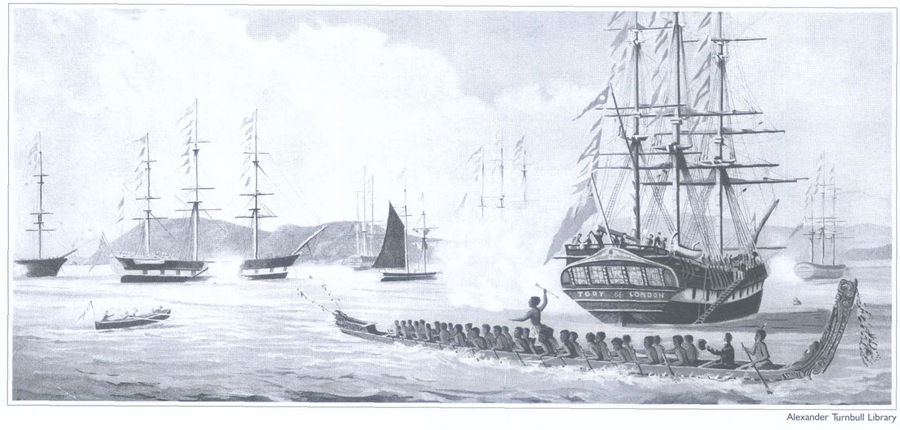

An artist's impression of the arrival of settlers at Port Nicholson, 1840.

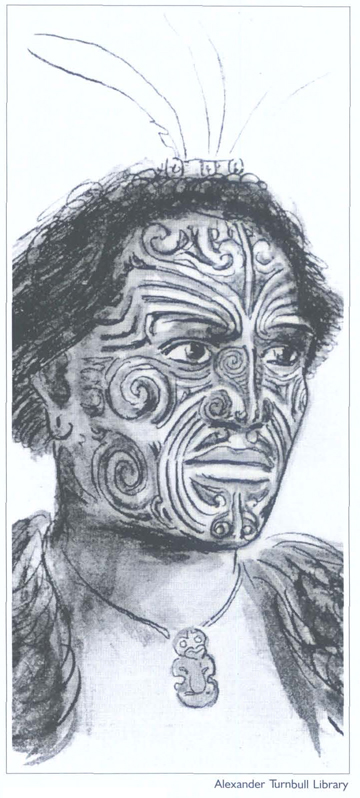

The Polynesian ancestors of the Māori (meaning ‘ordinary’) people settled the main New Zealand islands (Aotearoa) about 1,000 years ago. They arrived – whether initially by accident or design is unclear – in waka (canoes) blown across the subtropics by prevailing north-east winds.

The settlers soon lost contact with their home islands and were forced to adapt to Aotearoa's more challenging physical environment. Annual cultivation of kumara (sweet potatoes) – a perennial crop in the tropics – was possible in the north through the underground winter storage of tubers. Birds, fish and small animals were caught and the resources of forest and ocean gathered. The large moa (flightless birds similar to emu), which were numerous in Te Wai Pounamu (the South Island), were eventually hunted to extinction. Fires lit to flush them out removed much of the forest east of the Southern Alps and climatic changes made horticulture more difficult. Southern Māori increasingly lived in small hunter/gatherer groups and migrated seasonally to harvest resources.

Māori lived in groups of varying size that traced their descent from a common ancestor. Whānau (extended families of 10 to 30 people) were linked in hapū (subtribes), several of which made up an iwi. These distinctions were fluid: large whānau became hapū, and large hapū came to be seen as iwi, while other groups declined in status. Iwi said to have arrived on the same migratory canoe were linked in loose confederations.

All aspects of Māori life were interrelated, with economic and social activities carried out on behalf of the whole community. While land belonged to large groups, smaller groups had rights to use specific areas and resources. Families were headed by kaumātua (elders) and communities by rangatira (chiefs), whose persons and possessions were tapu (spiritually protected). Tapu also safeguarded cultivations and urupā (burial grounds) and helped maintain social order. Tapu was regulated by tohunga (experts), who mediated spiritual forces, retained tribal history and knowledge, and had expertise in carving, tattooing and canoe-building.

Tribal groups interacted through both trade and warfare. Regional products such as pounamu (jade) and tītī (shearwaters or petrels, known as ‘muttonbirds’) were often transported long distances for bartering. Information was also exchanged among tribes. Travel was by waka, or on foot along beaches, riverbeds and ridges. There were footpaths in more densely populated areas and tracks through forests.

One consequence of the slowness of travel was that even large iwi were unable to permanently conquer extensive areas. Instead, low-level warfare became endemic. Competition for mana (status) was complemented by competition for increasingly scarce land and resources. The concept of utu (reciprocity) generally ensured that at least one party to a dispute felt justified in maintaining it. Fighting usually occurred seasonally to fit in with cycles of subsistence. Most taua (raiding parties) made small-scale attacks, which caused few casualties. Sometimes, however, iwi were displaced into less desirable areas by military defeat or economic pressures. But many regions were occupied by the same descent group for long periods.

By the late 18th century, the Māori population was about 100,000. Most now lived in the north of Te Ika a Māui (the North Island), where pressure for land and other resources had become intense. Here communities became larger, with many pā (fortified settlements) sited on hilltops and protected by ditches and palisades. Hunting and trapping had declined as population density increased; fish and shellfish now complemented crops. Some iwi now numbered many thousands. Te Wai Pounamu remained sparsely populated.

Māori were generally relatively tall and sturdy, free from infectious diseases, adequately fed, and unlikely to die violently. Because of the dangers of childbirth, infant mortality and dietrelated dental problems, Māori life expectancy was about 30 years. This was similar to that of Europeans in the 17th century.

The first Europeans to reach Aotearoa were probably Abel Tasman's Dutch East India Company expedition in 1642. After four men were killed by local Māori when a landing was attempted in Golden Bay, Tasman sailed up the west coast of Te Ika a Māui without finding the ‘treasures or matters of great profit’ he sought. While this experience discouraged other Europeans from following in his wake, the name of a Dutch province (Zeeland) was given to a jagged line on maps of the Pacific.

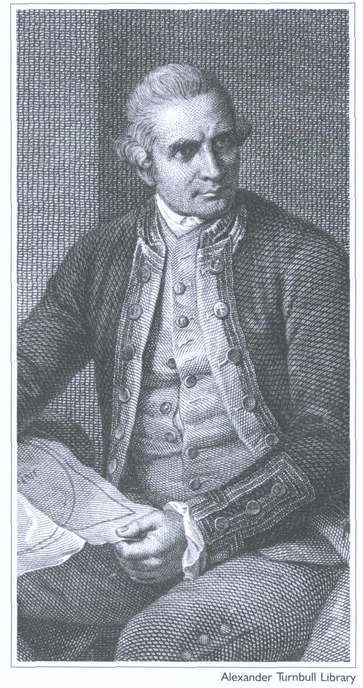

In 1769, two European expeditions visited Aotearoa. That of Frenchman Jean de Surville ill-treated Māori, provoking retaliation against later visitors. The arrival two months earlier of the English explorer James Cook, on a voyage with both scientific and economic goals, had enduring consequences. Cook's mostly peaceful interactions with ‘noble savages’ excited imaginations in Europe, and his discovery of Aotearoa's natural resources ensured it would not again be forgotten there.

Cook led two further expeditions which visited Aotearoa in the course of systematic exploration of the South Pacific. Following establishment of a penal colony at Sydney in 1788, New Zealand became an economic offshoot of New South Wales. Whaling and shore-based sealing began in the 1790s. Flax, timber, potatoes and pigs were being traded with visiting ships by the 1800s and Māori soon found they could barter this produce for firearms.

Muskets revolutionised Māori warfare. Fired in sufficient numbers, they generated enough terror to enable enemies who lacked them to be routed by traditional means. Unprecedently large and wide ranging Ngā Puhi taua settled old scores and generated new grievances across Te Ika a Māui during the 1820s. Other iwi exploited temporary leads in local arms races, in some cases using sailing ships to launch surprise attacks. Thousands were killed or enslaved, and tens of thousands displaced, provoking enduring disputes about land rights. By 1840, the ‘Musket Wars’ had subsided into an uneasy balance of terror.

Regular contact with Europeans had other negative consequences. Desired products could be purchased only through debilitating labour, often in unhealthy environments. Māori were vulnerable to infectious diseases, from which many died from the 1790s. The Māori population was halved during the 19th century.

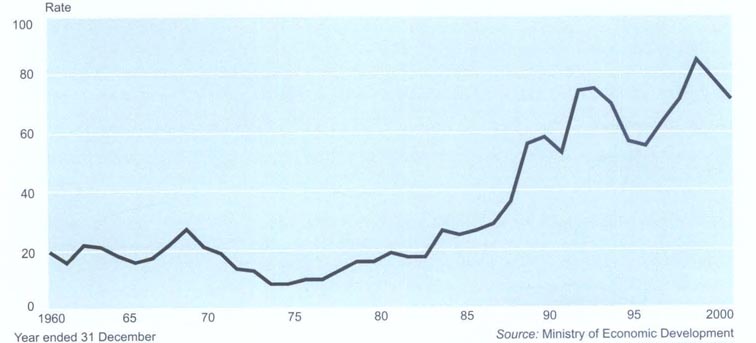

Māori social structures were also disrupted. Mana became linked to the acquisition of European goods and the Pākehā (Europeans) who provided access to them. In the early 19th century, these were mostly whalers in the South Island – where communities soon included ‘half-caste’ children – and missionaries in the North Island. Māori initially resisted Christianity, but embraced the skills through which it was communicated – reading and writing. Literate slaves acquired status, while the mana of illiterate chiefs fell. Knowledge, previously held in common or tied to specific roles, could now be possessed and communicated by anyone.