Acknowledgements

This publication was produced in the Information Services Division of the Department of Statistics.

Deputy Government Statistician: L. W. Cook.

Manager: K. W. Eddy.

Editor: R. W. White.

Assistant editors: J. H. Macdonald; E. Stone; I. R. Malcolm.

Maps and diagrams: P. J. McGrath; M. A. Metcalfe.

Cover design: A. J. Stewart.

Photograph editor: A. J. McCredie.

Proofreading: J. W. Hunt; M. S. Page.

Cover

Rita Angus, Sheds, Hawke's Bay 1965–66,

oil on hardboard 585 X 600 mm.

Private collection, Auckland.

Rita Angus (1908–70) was a New Zealand painter who tried through her landscapes to capture the distinctive colour and hard light of New Zealand.

NEW ZEALAND OFFICIAL YEARBOOK

CAT. NO. 01.001

ISSN 0078-0170

RECOMMENDED RETAIL PRICE $49.50

(INCL. GST)

Table of Contents

List of Tables

- 1.2. PRINCIPAL MOUNTAINS

- 1.3. PRINCIPAL RIVERS*

- 1.4. PRINCIPAL LAKES*

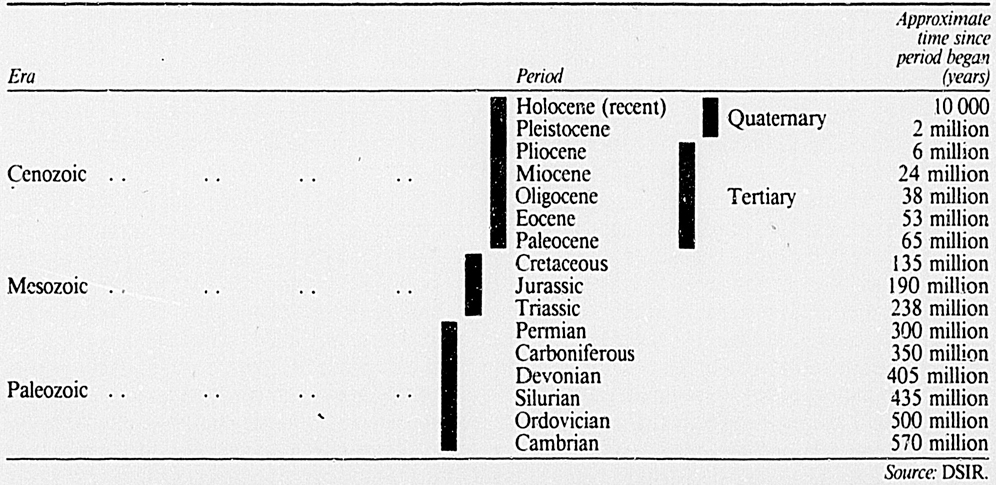

- 1.5. GEOLOGICAL TIMESCALE

- 4.2. DEFENCE EXPENDITURE

- 4.5. STATE OF THE NAVY

- 4.6. STRENGTH OF THE NAVY

- 4.7. STATE OF THE ARMY

- 4.8. STRENGTH OF THE ARMY

- 4.9. STATE OF THE RNZAF

- 5.2. POPULATION CHANGE

- 5.10. POPULATION OF CITIES

- 5.11. POPULATION OF BOROUGHS

- 5.12. POPULATION OF COUNTIES

- 5.13. POPULATION OF DISTRICTS

- 5.15. ARRIVALS IN NEW ZEALAND

- 5.20. BIRTHS

- 5.21. SEX OF CHILDREN BORN

- 5.26. EX-NUPTIAL BIRTHS

- 5.28. ADOPTIONS

- 5.29. STILLBIRTHS

- 5.32. DEATH RATES

- 5.33. AVERAGE AGE AT DEATH*

- 5.34. LIFE EXPECTANCY

- 6.2. TYPES OF DWELLINGS

- 6.9. HOUSEHOLD TRANSPORT

- 6.13. HOUSEHOLD AMENITIES

- 6.15. MARRIAGE RATES

- 6.18. DE FACTO RELATIONSHIPS*

- 6.24. CUSTODY ORDERS, 1986

- 6.26. RELIGIOUS PROFESSIONS*

- 6.42. TYPES OF SUBMISSIONS

- 7.23. CHILDREN AND YOUNG PERSONS UNDER THE CONTROL OF THE SOCIAL WELFARE

DEPARTMENT, 30 NOVEMBER 1986

- 8.16. PRIVATE HOSPITAL BEDS*

- 8.17. STAFF EMPLOYED BY HOSPITAL BOARDS AND IN HOSPITALS UNDER THE CONTROL

OF THE DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH

- 8.18. HOSPITAL BOARD BORROWING

- 8.24. PSYCHIATRIC AND INTELLECTUALLY HANDICAPPED PATIENTS: NUMBERS AND RATES

(PER 100 000 MEAN POPULATION)

- 8.35. DROWNINGS, 1987 P

- 9.7. PRIMARY SCHOOLS

- 9.9. SECONDARY SCHOOLS

- 9.10. STUDENT NUMBERS

- 9.11. TEACHING STAFF

- 9.19. UNIVERSITY STAFF, 1987*

- 9.20. UNIVERSITY STUDENTS

- 10.7. CRIMINAL TRIALS

- 10.10. APPEALS IN HIGH COURT AGAINST CONVICTIONS OR ORDERS AND/OR SENTENCES

IMPOSED IN DISTRICT COURTS

- 10.14. PENAL INSTITUTIONS*

- 11.4. MEDIA ADVERTISING, 1987*

- 11.7. RACE MEETINGS*

- 11.12. DOMESTIC TRAVEL DESTINATIONS

- 12.1. THE LABOUR FORCE*

- 12.3. HOURS OF WORK*

- 12.10. UNEMPLOYMENT 1951–86*

- 12.15. WEEKLY EARNINGS

- 12.19. PROFILE OF WORKERS' UNIONS

- 14.13. LAND USE TODAY

- 15.8. FERTILISER APPLICATION

- 15.12. FARMING INPUTS PRICE INDEX*

- 15.15. SHEEP CATEGORIES

- 15.16. SIZE OF SHEEP FLOCKS

- 15.17. CATTLE CATEGORIES

- 15.18. MEAT PRODUCTION

- 15.20. MEAT EXPORT PRODUCTION

- 15.21. MEAT BOARD LEVIES, 1987

- 15.22. LAMB GRADES

- 15.23. BEEF GRADING SYMBOLS

- 15.24. LONDON WHOLESALE IAMB PRICES

- 15.26. WOOL PRODUCTION*

- 15.27. WOOL SOLD AT AUCTION

- 15.32. DAIRY FACTORY PRODUCTION

- 15.33. TOWN MILK

- 15.34. DAIRY EXPORT EARNINGS

- 15.37. PIGS

- 15.38. POULTRY FLOCKS*

- 15.41. GRAIN AND PEAS, 1986*

- 15.42. AREAS PLANTED IN FRUIT

- 15.43. WINE STOCKS

- 15.44. WINE PRODUCTION AND SALES

- 16.5. ROUNDWOOD PRODUCTION

- 16.12. VOLUME OF TIMBER IMPORTS

- 16.13. VOLUME OF TIMBER EXPORTS

- 16.17. FISHERIES EXPORTS

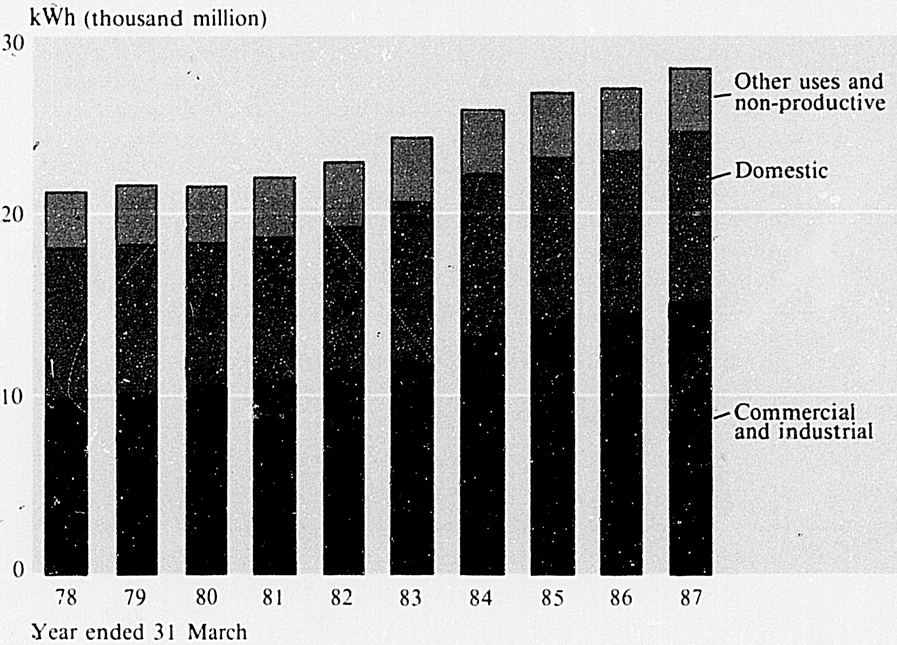

- 17.9. ELECTRICITY SOURCES

- 17.11. ELECTRICITY MARKETS

- 17.12. POWER STATIONS 1987

- 17.14. NATURAL GAS SUPPLY

- 17.15. MINE AND QUARRY PRODUCTION

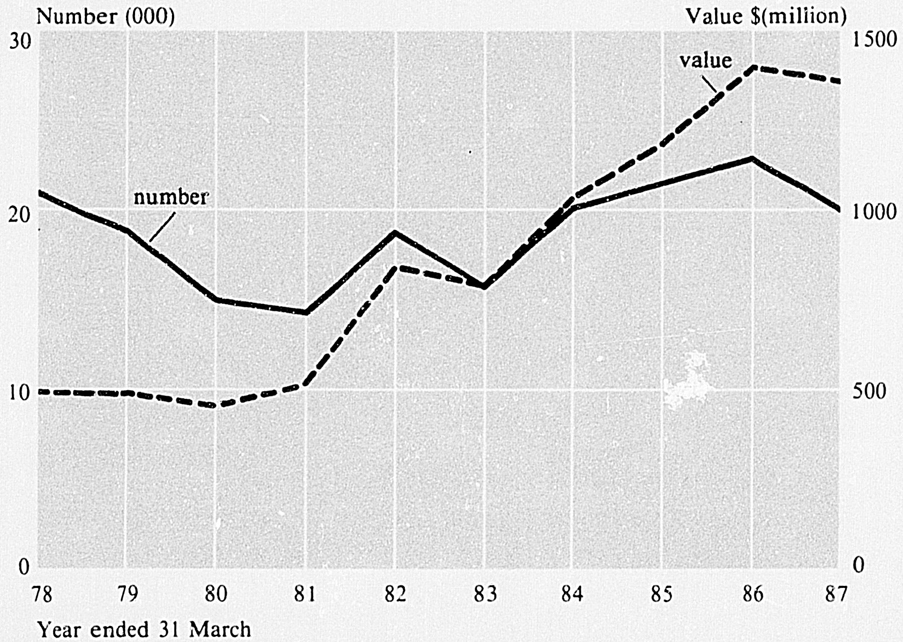

- 19.1. RESIDENTIAL PRICES

- 19.13. PERMITS FOR NEW DWELLINGS

- 19.14. WORK PUT IN PLACE

- 19.14a. WORK PUT IN PLACE

- 19.15. BUILDING MATERIAL PRODUCTION

- 20.17. SUMMARY OF AERIAL WORK

- 20.21. PUBLIC ROADING EXPENDITURE*

- 20.23. LICENSED MOTOR VEHICLES

- 20.28. TRAFFIC OFFENCES REPORTED*

- 20.31. OVERSEAS MAILS

- 20.33. TELEPHONE SERVICES

- 21.1. COMPANY REGISTRATIONS

- 21.2. BANKRUPTCIES

- 21.3. OCCUPATIONS OF BANKRUPTS

- 21.5. COMPANY INSOLVENCIES

- 21.21. RETAIL TRADE SURVEY: SALES*

- 21.22. RETAIL TRADE SURVEY: STOCKS

- 21.24. HIRE-PURCHASE SURVEY*

- 21.25. VALUE OF CREDIT CARD SALES

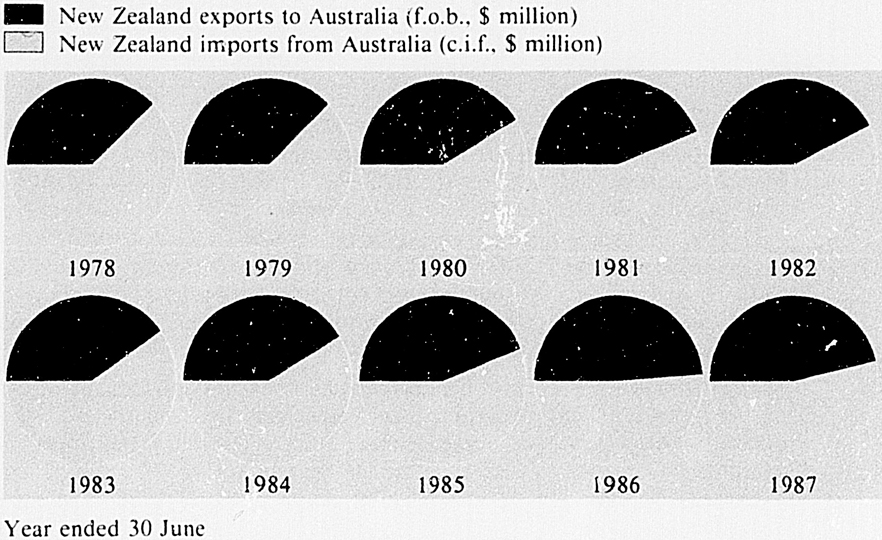

- 22.3. TRADE WITH AUSTRALIA

- 22.8. EXPORT PRICE INDEX*

- 22.9. EXPORT PRICE INDEX*

- 22.10. IMPORT PRICE INDEX*

- 22.13. EXPORT VOLUME INDEX*

- 22.14. IMPORT VOLUME INDEX*

- 23.1. PRICE INDEXES SUMMARY*

- 24.7. FOREIGN EXCHANGE RATES*

- 25.10. RATES OF STAMP DUTY

- 25.11. RATES OF GIFT DUTY*

- 25.12. SUMMARY OF TAX REVENUE

- 25.13. RECEIPTS OF TAXATION

- 25.15. INCOME OF COMPANIES

- 25.19. INTEREST PAYMENTS

- 26.7. CAPITAL FINANCE

- 26.8. EXTERNAL TRANSACTIONS

- 26.12. INCREASE IN STOCKS

Table of Contents

The 93rd edition of the New Zealand Official Yearbook continues our tradition of providing an authoritative description of a country and its people in one volume.

Since 1893 the Yearbook has given New Zealand and overseas readers an Introduction to the nation's social, economic and cultural life and institutions. For specialist users, it is designed as a first point of reference, with relevant basic statistics and reference material, as well as directions to further sources of information.

Compilation of this edition of the Yearbook has gone on amid sweeping reforms in many areas of the New Zealand society and economy. The editors have made every effort to keep information on institutions and legislation current, with a cut-off date of September 1988. However, some statistical series are slower to reflect change, and there may be some minor inconsistencies between the text and tabular material.

Revision of the structure and presentation of the Yearbook has continued. Several chapters have been substantially revised and many subject areas have been augmented. The number and variety of graphics has also increased.

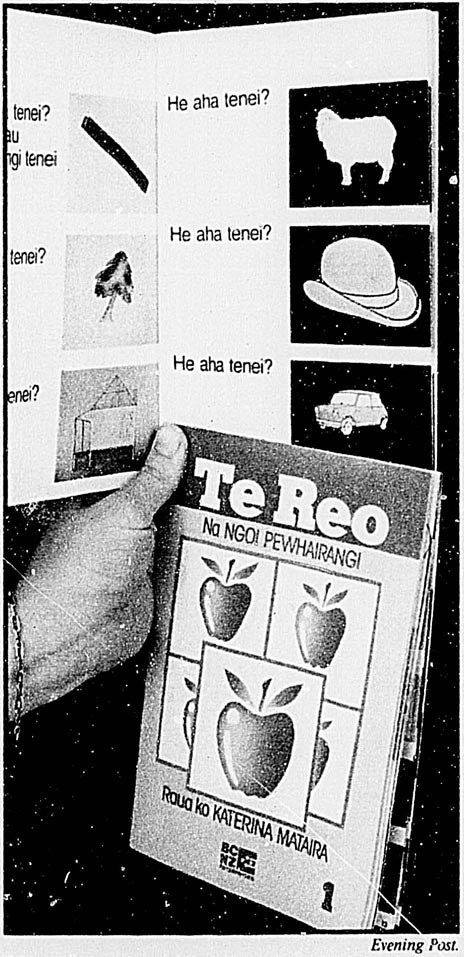

There is a strong focus on social issues; with special articles on the Maori language, immigration policy, and the Royal Commission on Social Policy (which reported during 1988).

This is the last edition of the Yearbook produced in the current format. Major changes are now being planned, both to further upgrade the publication, and to reflect New Zealand's 1990 celebrations.

The Department of Statistics can only publish the Yearbook with the help of contributions from many other government departments and official organisations. I would like to again thank all contributors, the Government Printing Office, and departmental editorial staff for their efforts.

S. Kuzmicich,Government StatisticianOctober 1988.

| 70 Symonds Street | Private Bag |

| AUCKLAND | Telephone (09) 31-055 |

| Aorangi House | PO Box 2922 |

| 85 Molesworth Street | Telephone (04) 729-119 |

| WELLINGTON | |

| MFL Building | Private Bag |

| 749 Colombo Street | Telephone (03) 793-700 |

| CHRISTCHURCH | |

| or | |

| Census of Population and Dwellings | Private Bag |

| Winchester House | Telephone (03) 791–716 |

| 64 Kilmore Street | |

| CHRISTCHURCH | |

| Norwich Union Building | Private Bag |

| Corner Bond and Rattray Streets | Telephone (024) 777-511 |

| DUNEDIN |

The Department of Statistics has an information desk at every office. In answer to a letter, visit, or telephone call, information officers can provide statistical information, or tell you more about the department's other services, including access to statistics on the INFOS computer data base.

Table of Contents

As a new reader of the New Zealand Official Yearbook you may be surprised at the range of information within its pages. But, like any other reference work, the Yearbook is only as effective as its information is accessible. The following notes are therefore included to familiarise you with the book.

During its long history the aims and functions of the New Zealand Official Yearbook have changed with the times. Today, its editors publish with two main purposes in mind. Firstly, it is a compendium of facts and figures on New Zealand. Secondly, it is an annual describing major changes in New Zealand's administrative framework for the year preceding publication.

The Yearbook does not usually contain the latest or most detailed statistics on particular topics, but it does tell its readers where the latest, or more detailed, figures or information are available.

There are two likely ways you will look for information.

If your question is general, for example “How is New Zealand governed?”, then you will probably refer firstly to the table of contents (beginning overleaf) which lists not only chapter headings but major sections within chapters. In approaching the book this way it is worth bearing in mind that the 26 chapters follow a ‘logical’ progression. The first few chapters describe the physical setting as well as New Zealand's history, system of government and international relations. A description of its people comes next, followed by social framework and institutions. Chapters 12–21 describe New Zealand's work-force and industries, while the final chapters of the book discuss the nation in broad economic terms.

Throughout the book cross references are made, usually by reference to numbered sections within chapters (which appear at the head of each right hand page).

If, on the other hand, your question is more specific, for example “How many people drown while boating each year?”, then the book is thoroughly indexed, and a brief note on the system used can be found at the beginning of the index.

Because the Yearbook covers such a broad range of subjects, few of its statistics are being published for the first time. Many statistics from government departments and other organisations have been published late in the year preceding publication.

For this edition the figures published are at least the latest available at 1 January 1988.

If the source of a particular table is other than the Department of Statistics, then it is noted at the base of the table. Tables are usually for the year ended 31 March, or for the calendar year. Most tables indicate the months in which the years end, and where a single year is indicated and no month is mentioned the figures can be assumed to be for the calendar year. Where two years are given together, e.g., 1986–87, and no month is mentioned, it can be assumed the figures are for the year ended 31 March.

The following symbols are used in all the tables:

Figures are often rounded-off to the nearest thousand or some convenient unit. Sometimes this rounding results in tables with totals which disagree slightly with the total of the individual items shown.

Statistics from the 1981 and 1986 Censuses of Population and Dwellings have been subject to a process of random rounding, whereby all cell values, including row and column totals, have been rounded. Individual figures will therefore not necessarily add up to the stated totals.

Weights and measures, and a glossary of statistical terms used, are given at the back of the book.

If you require general information on a topic, the ‘Further information’ section at the end of each chapter provides a brief list of official publications relevant to that chapter. The bibliography, Books about New Zealand, lists current books on New Zealand under subject headings. It is followed by a list of some of the publications of the Department of Statistics.

Contributing organisations are also listed in the order of appearance at the end of each chapter.

Major changes are planned for the next edition of the Yearbook, which will appear in 1990. The new book will be slimmer and reflect the celebrations in that year.

Your suggestions for the contents of it and subsequent Yearbooks are welcome. Send them to the Editor, New Zealand Official Yearbook, Department of Statistics, PO Box 2922, Wellington.

Maps and diagrams

| Location of earthquakes and volcanic activity | 8 |

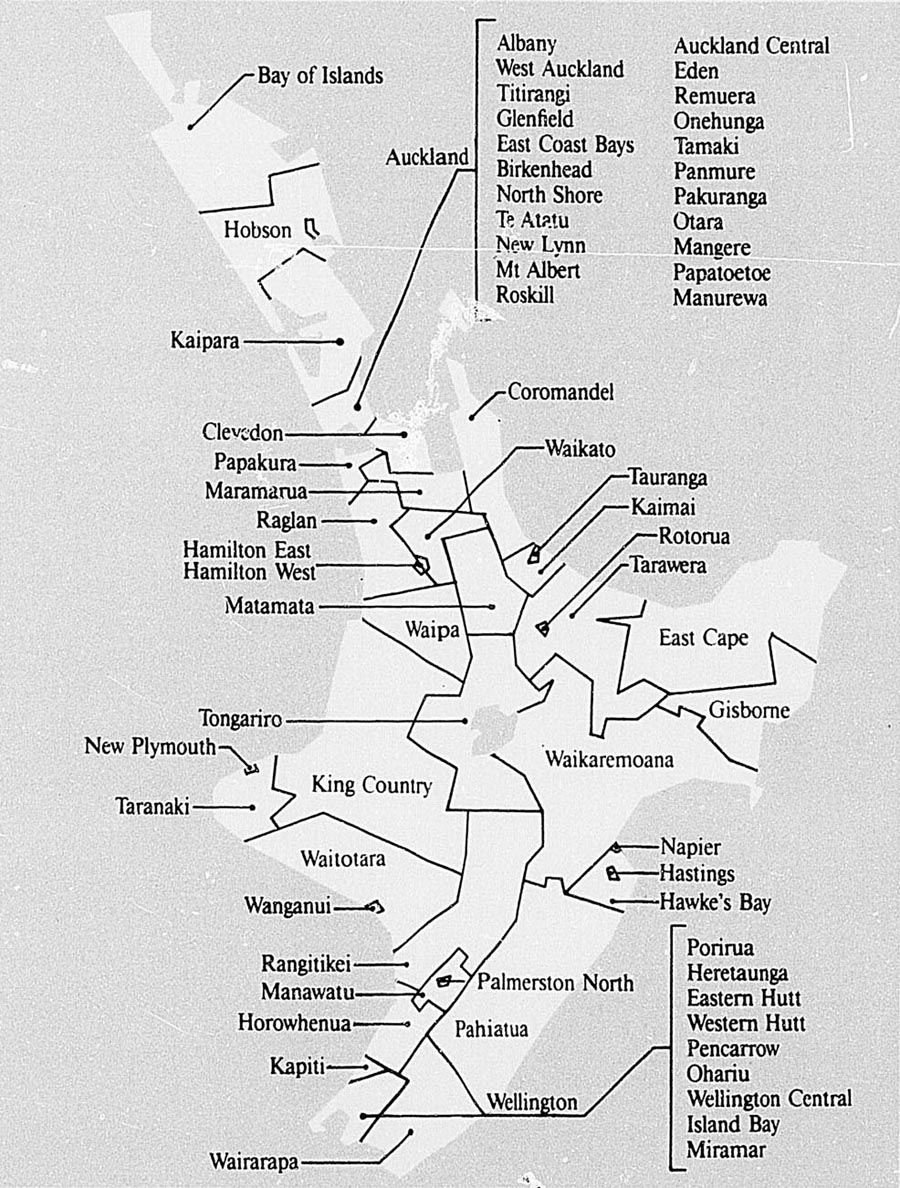

| 1987 Electoral districts—North Island | 71 |

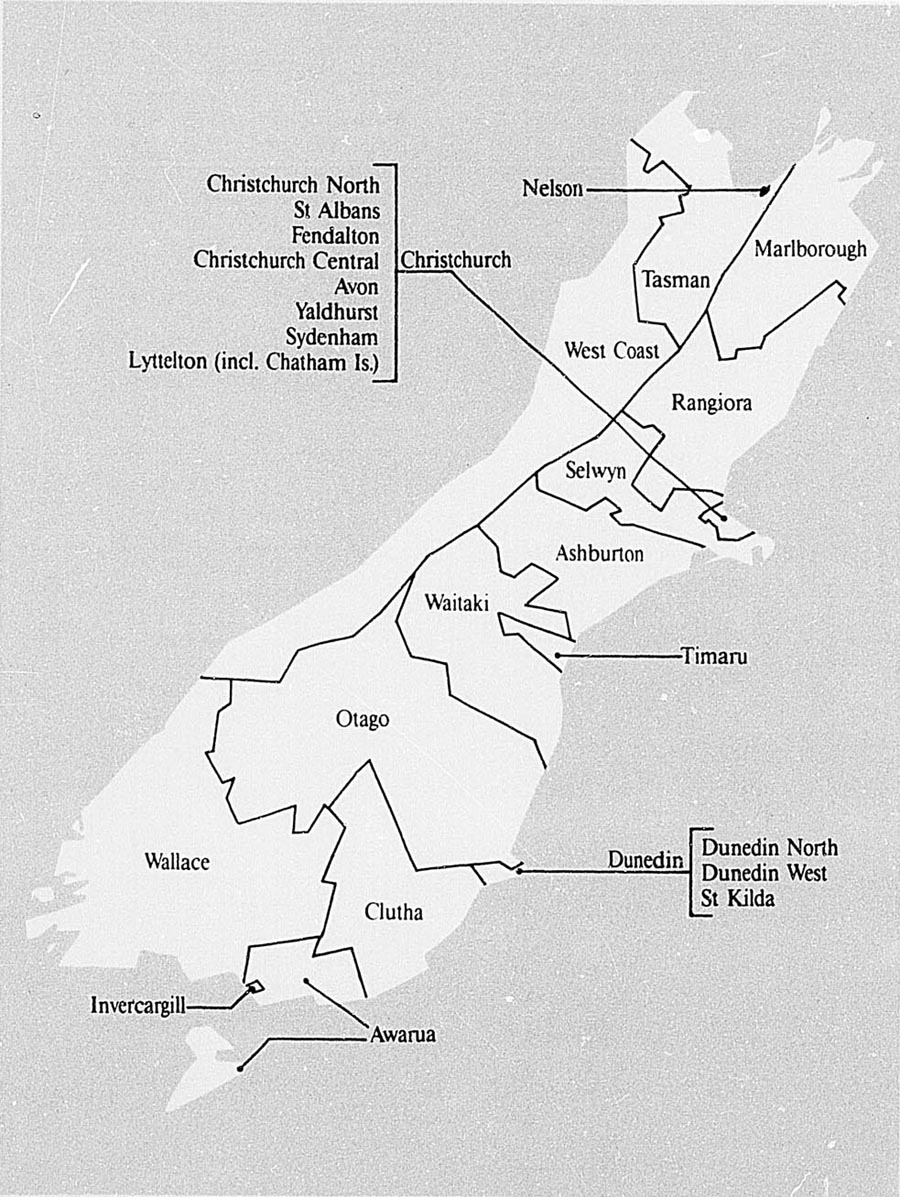

| 1987 Electoral districts—South Island | 72 |

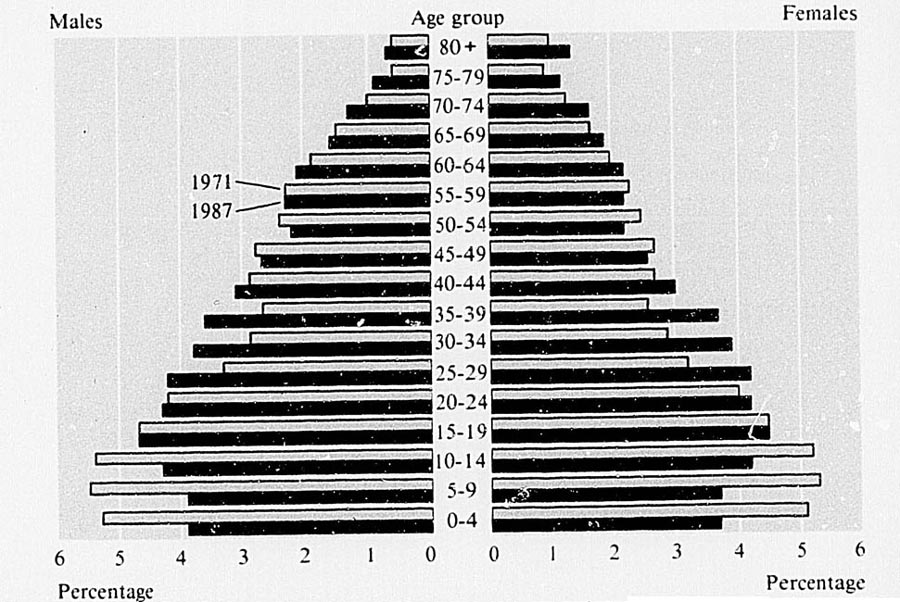

| Age pyramid of population by sex 1971 and 1987 | 141 |

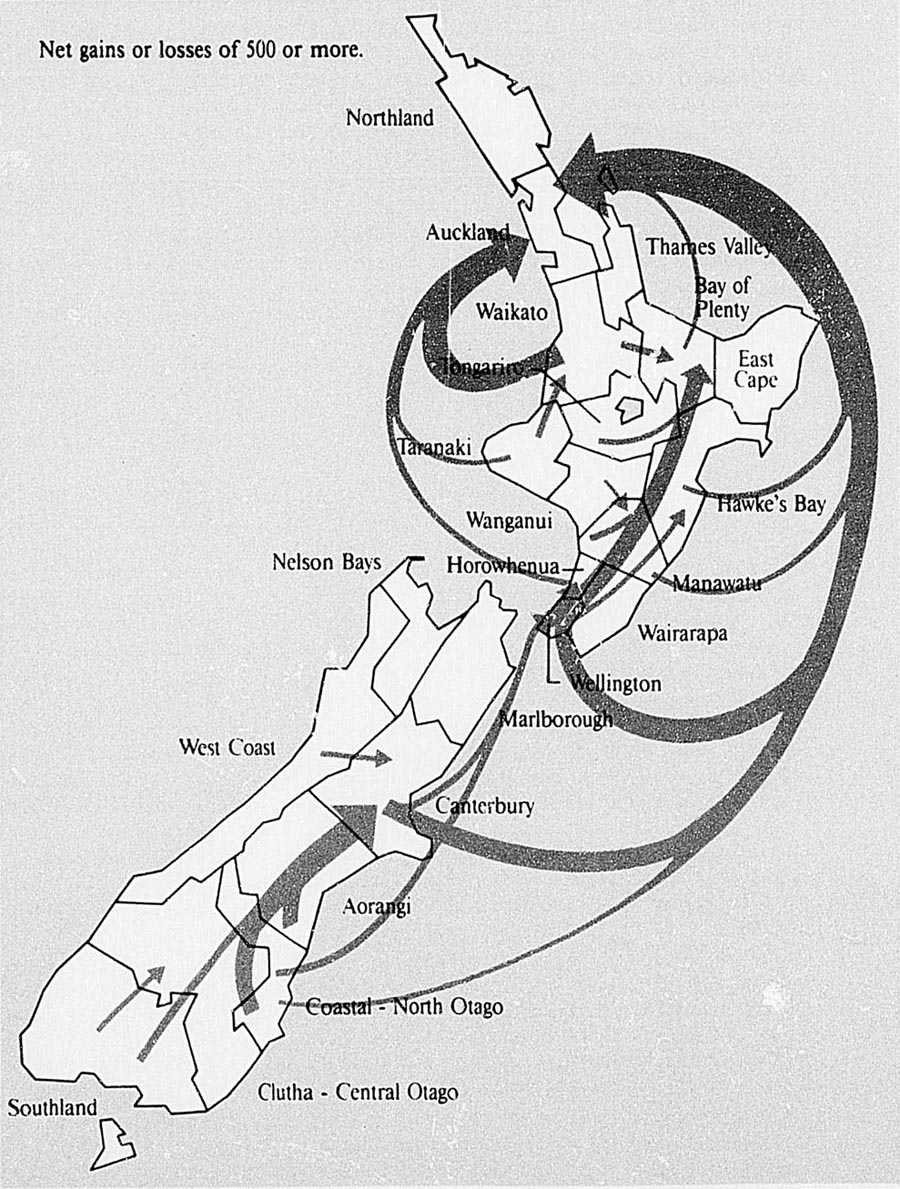

| Migration patterns between local government regions, 1976–81 | 144 |

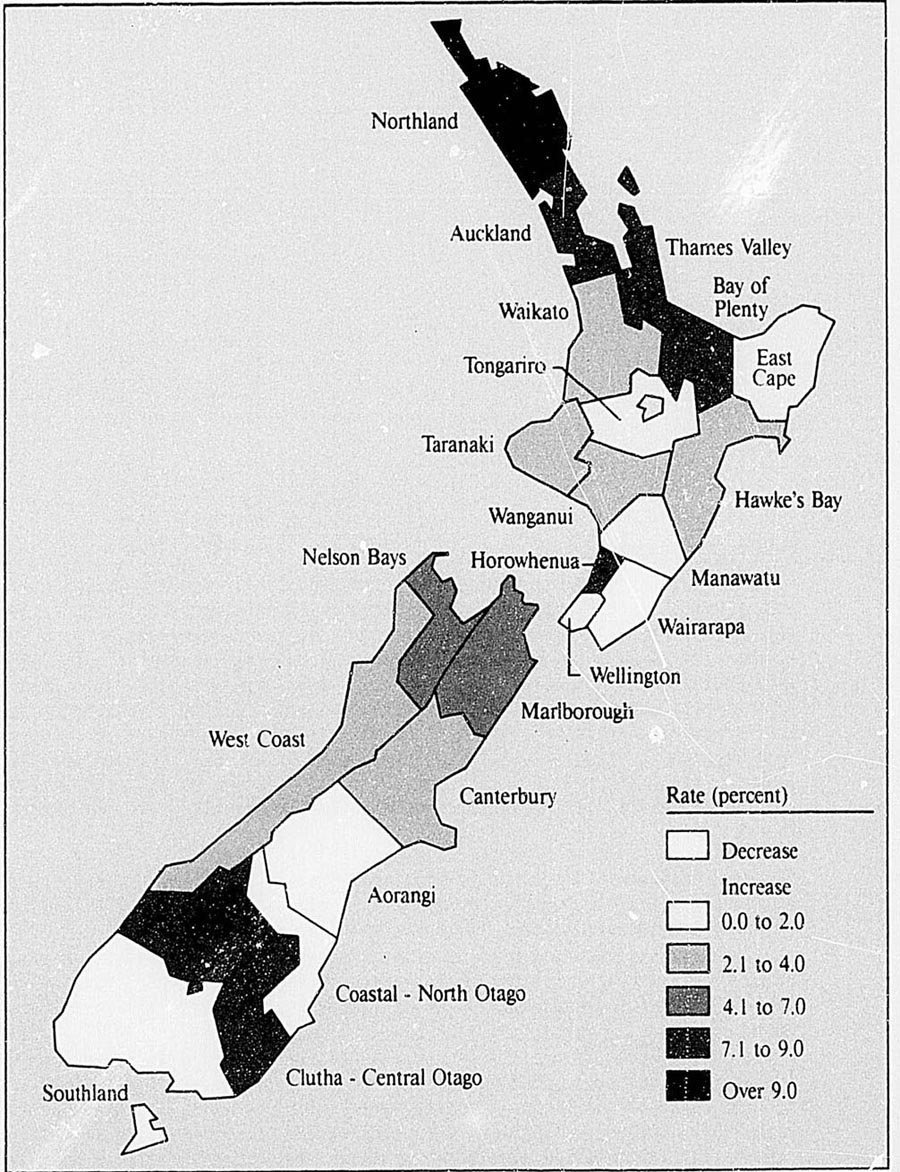

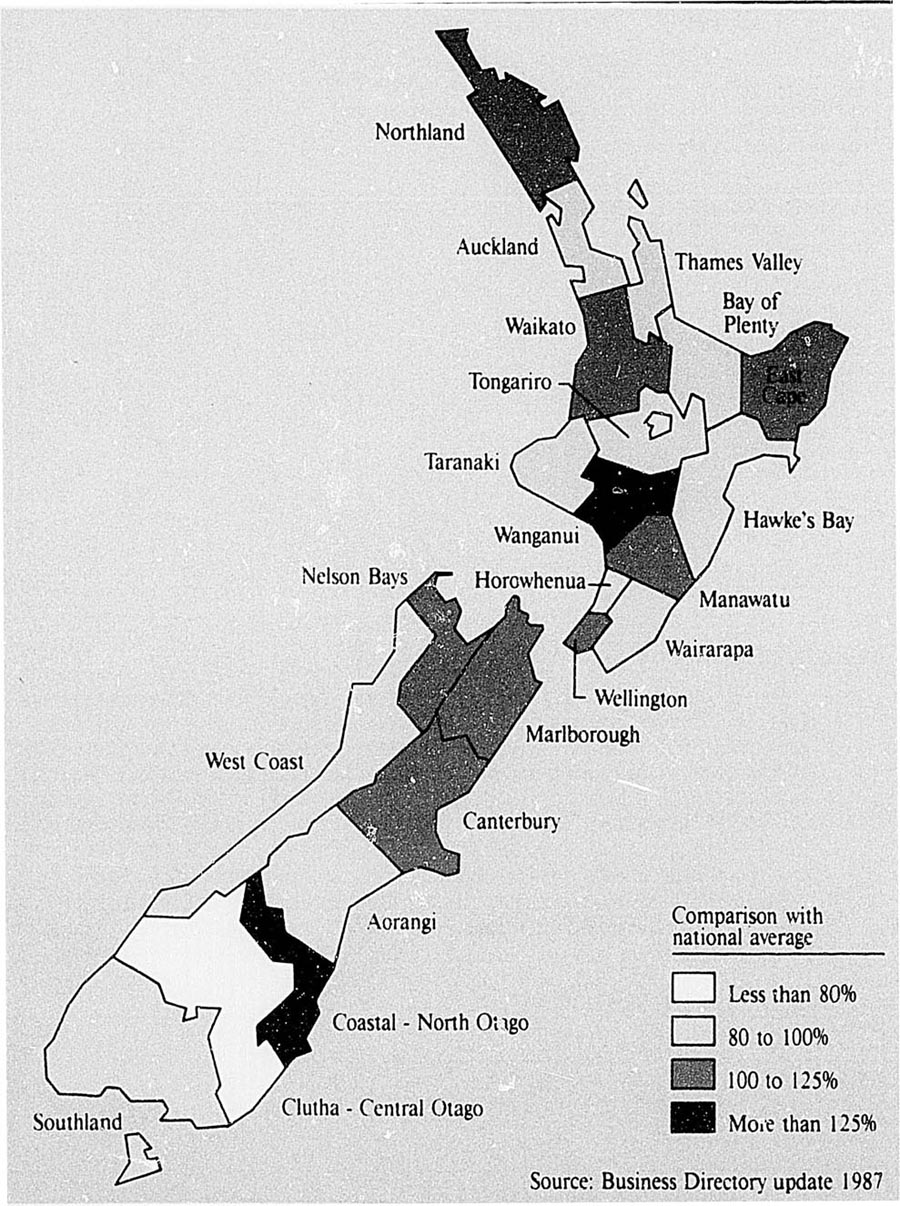

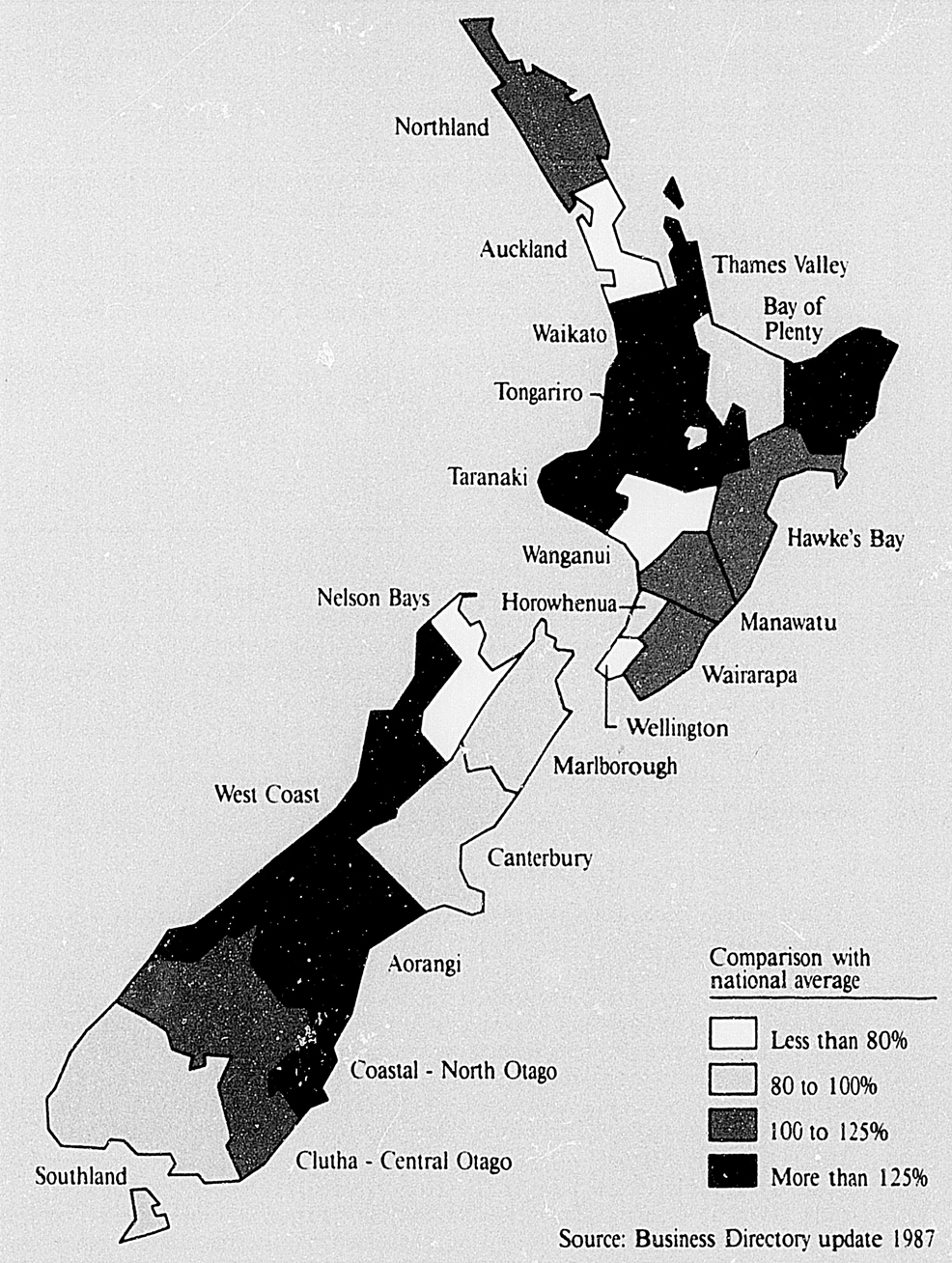

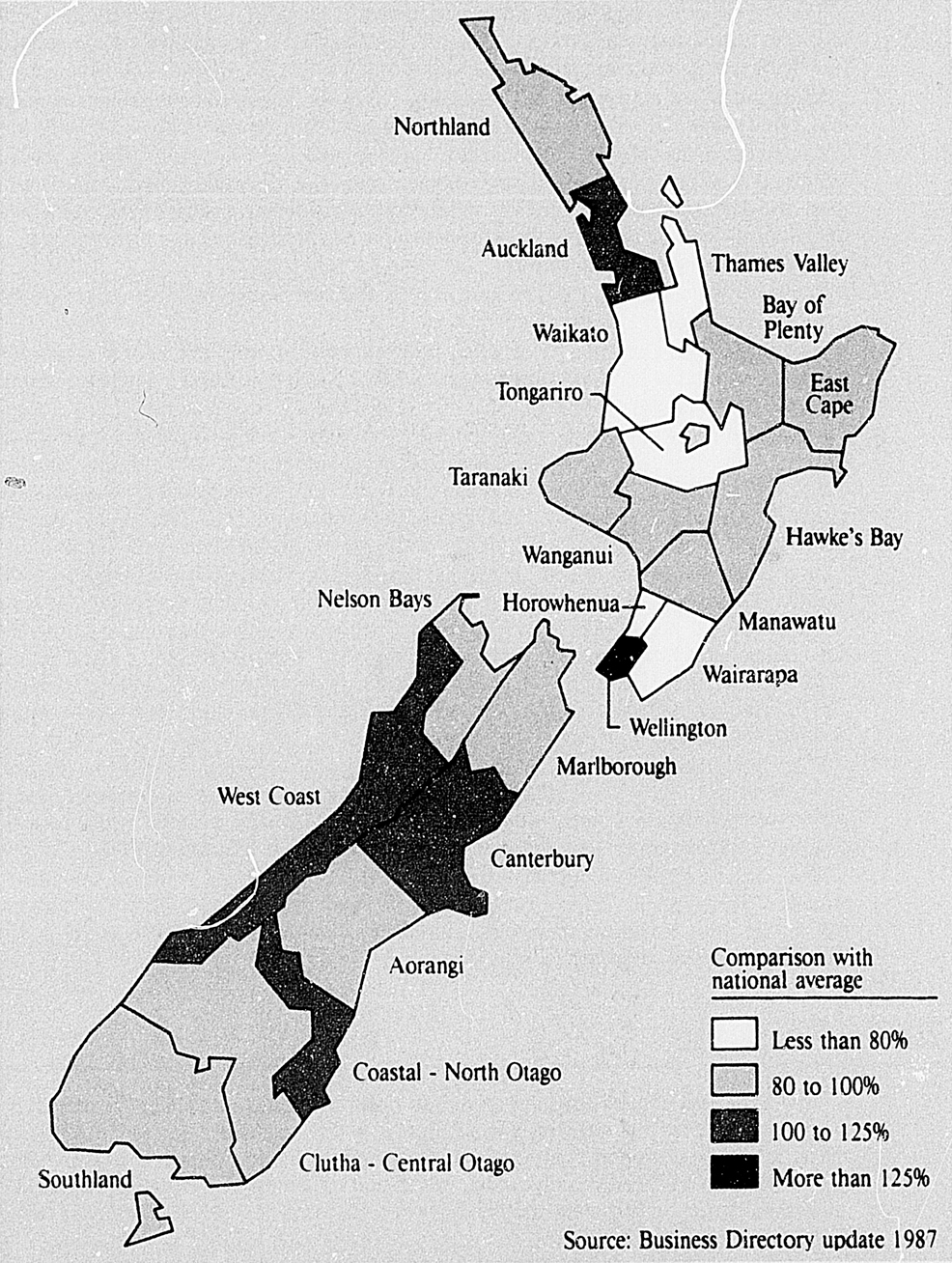

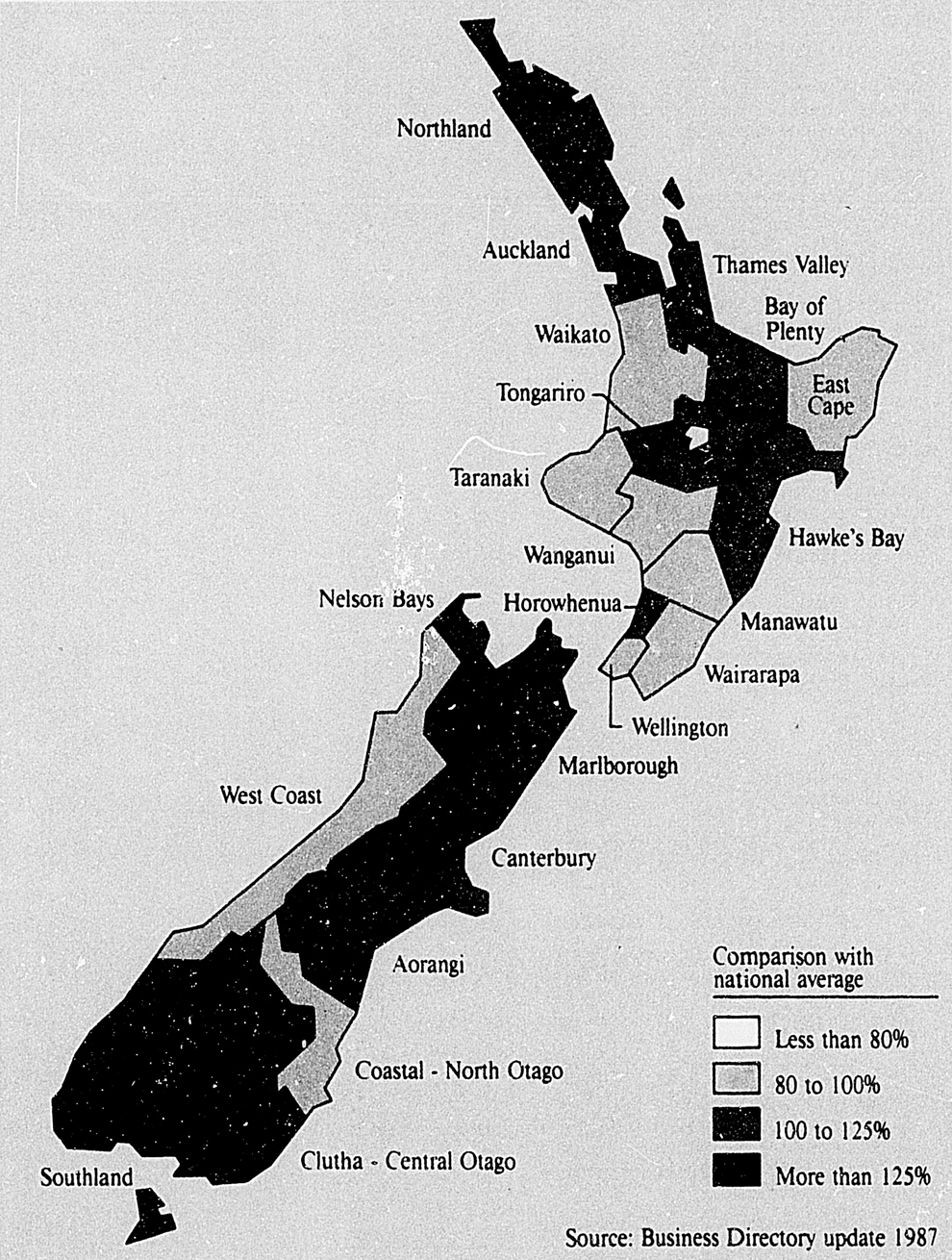

| Rate of change in total population 1981–86 | 147 |

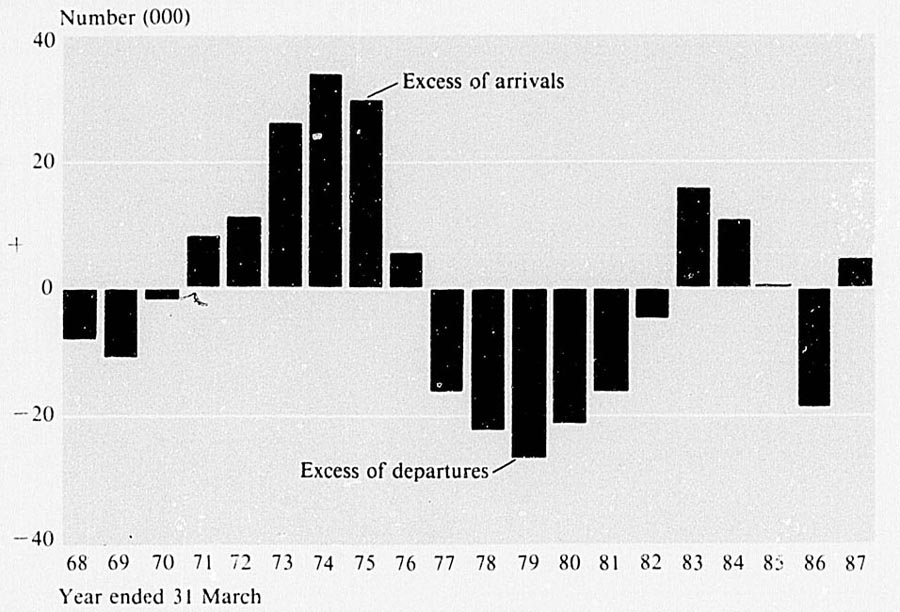

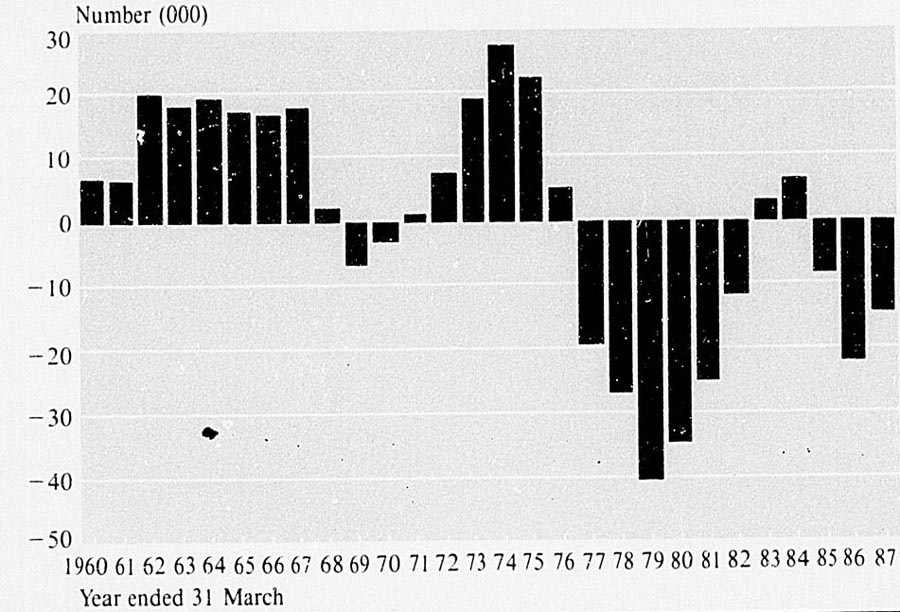

| External migration—excluding through passengers and crew | 156 |

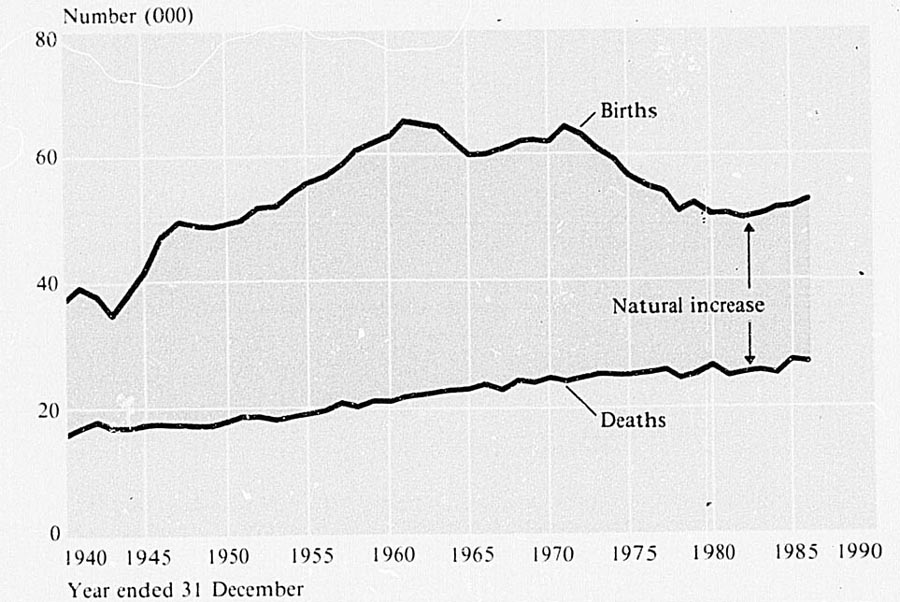

| Vital statistics | 162 |

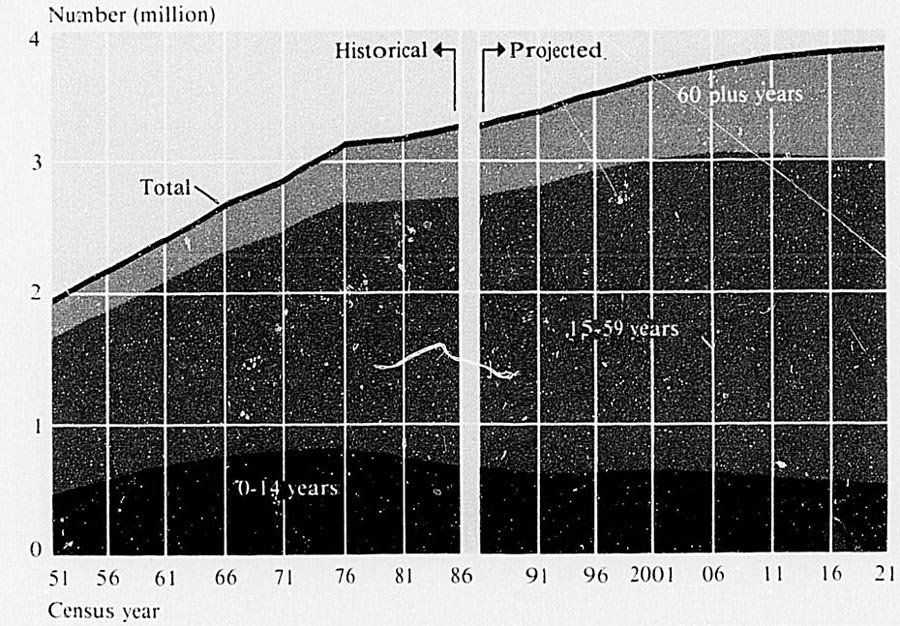

| Age of population—historical and projected | 165 |

| Percentage of workforce employed in community, social and personal services | 176 |

| Net population change—through permanent and long-term migration | 196 |

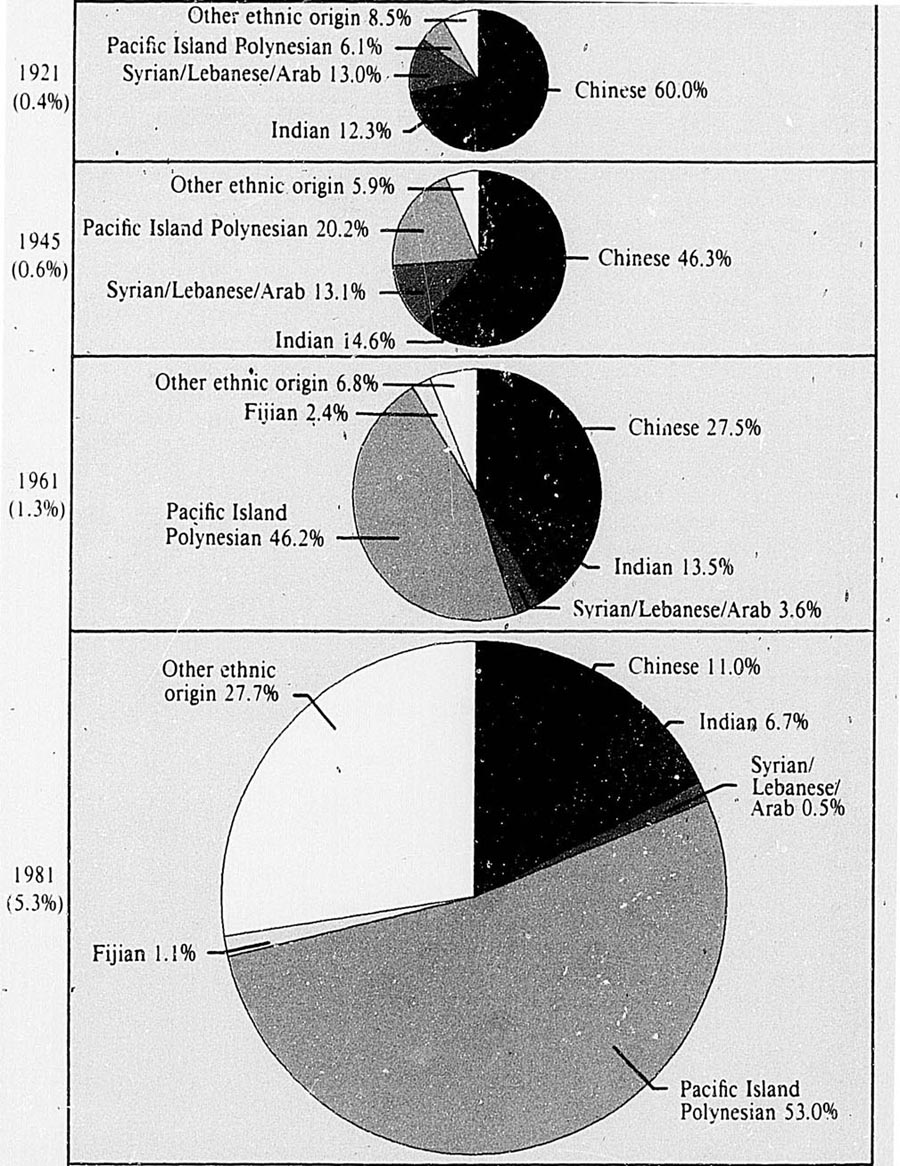

| Percentage of population other than European and Maori | 199 |

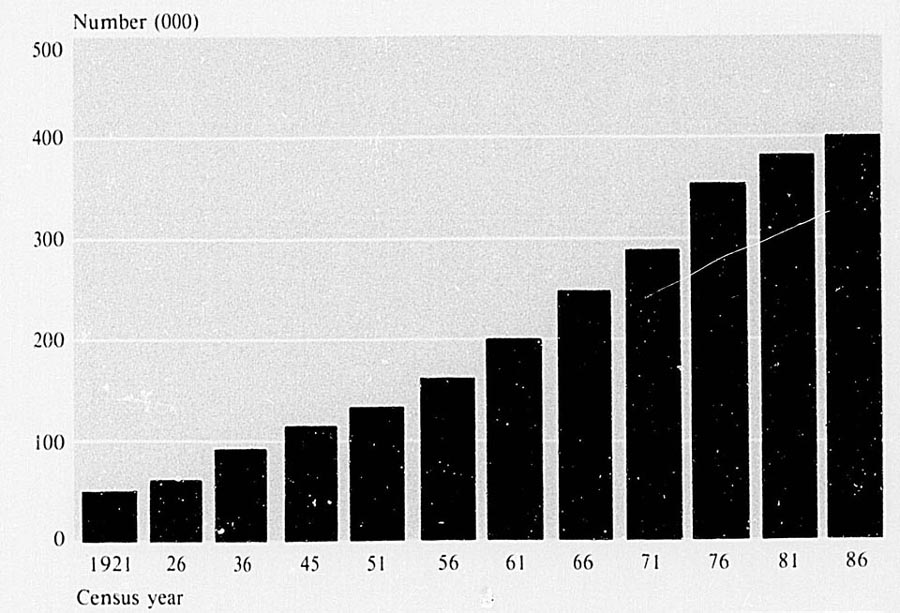

| Maori population | 209 |

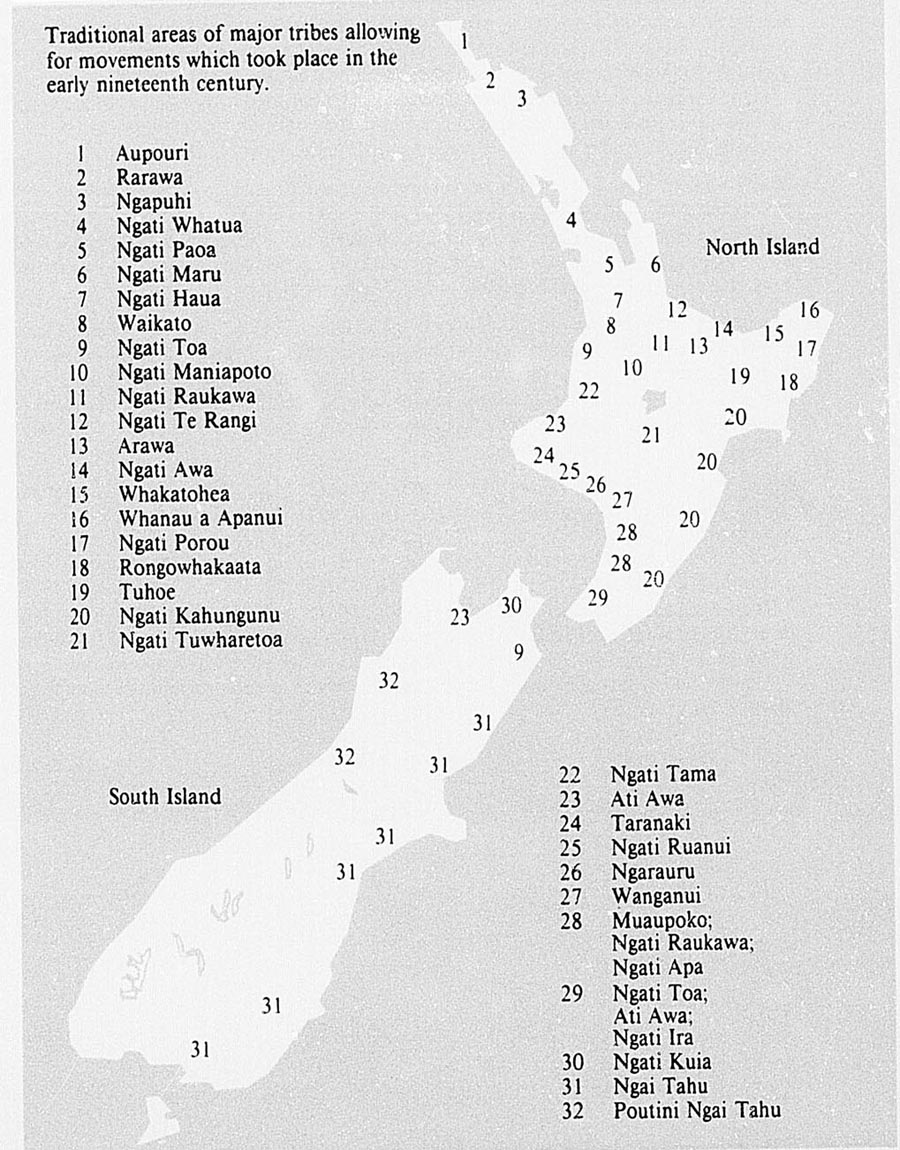

| Maori tribal locations | 215 |

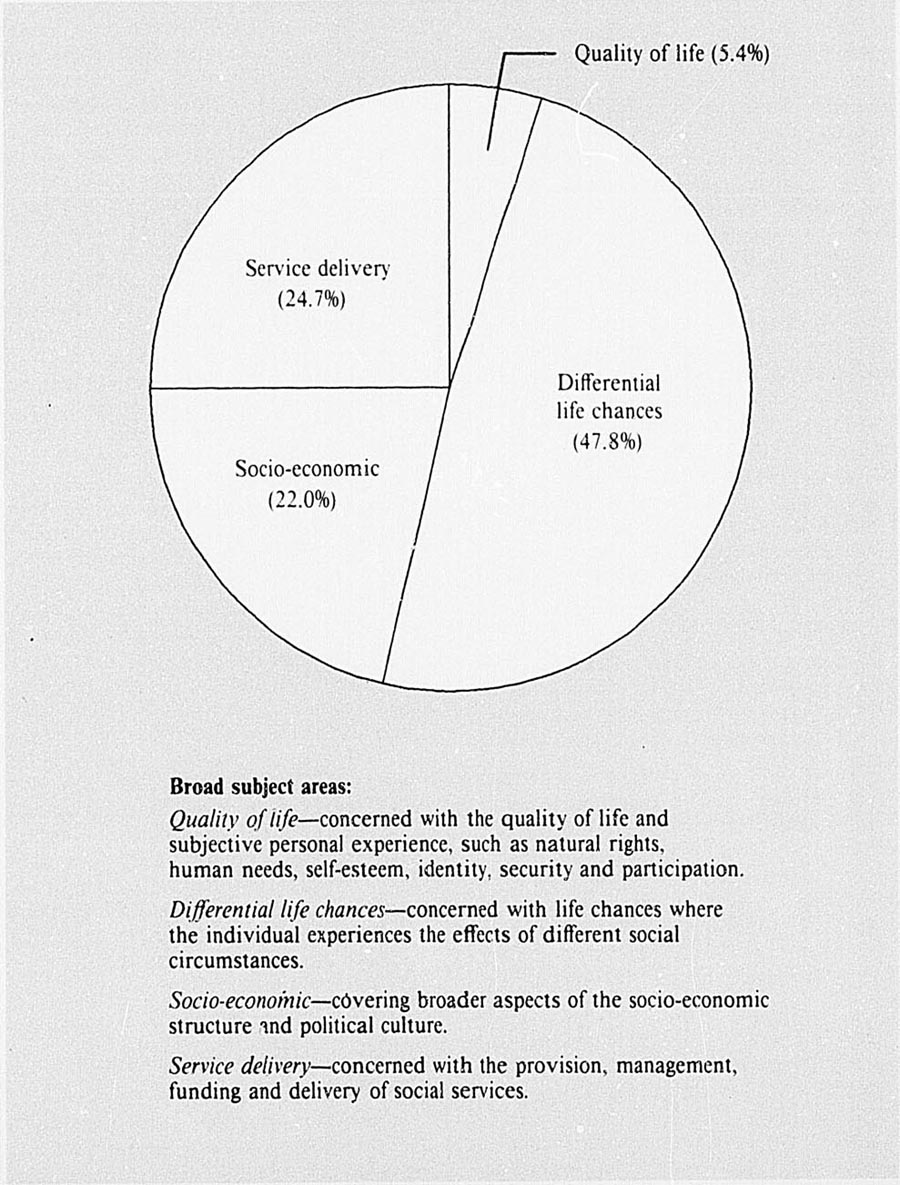

| Royal Commission on Social Policy—subject areas covered by submissions | 235 |

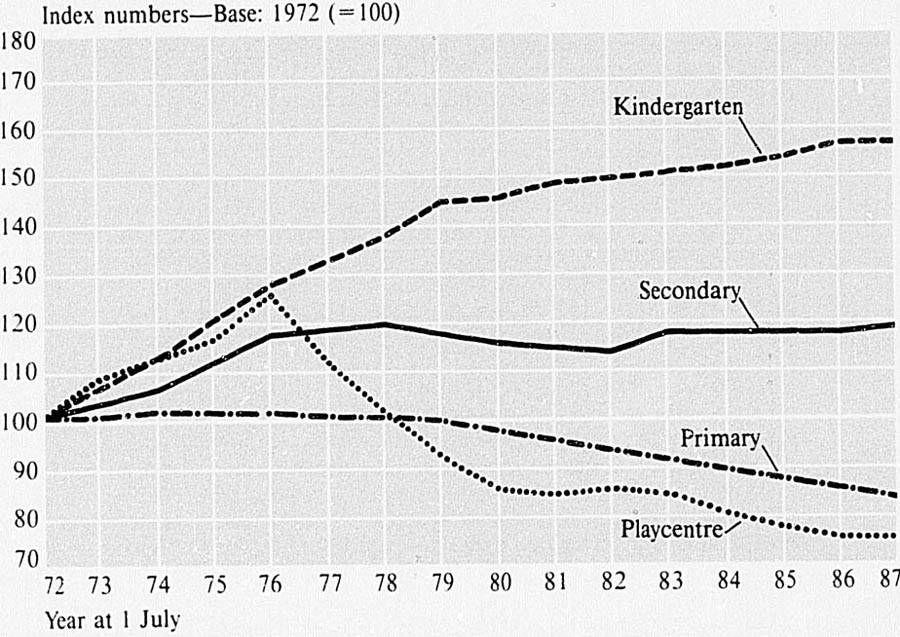

| Enrolment growth—up to secondary level | 351 |

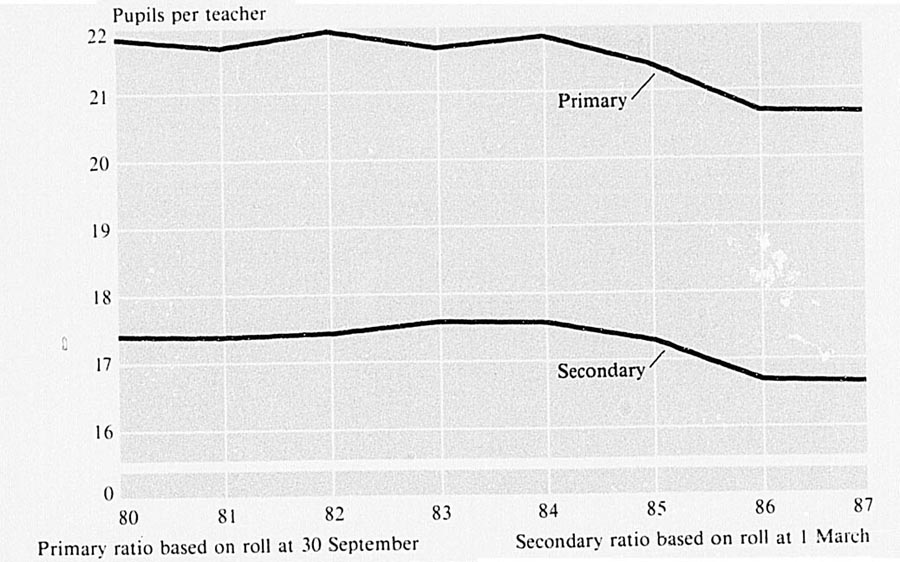

| Teacher-pupil ratio in state schools | 354 |

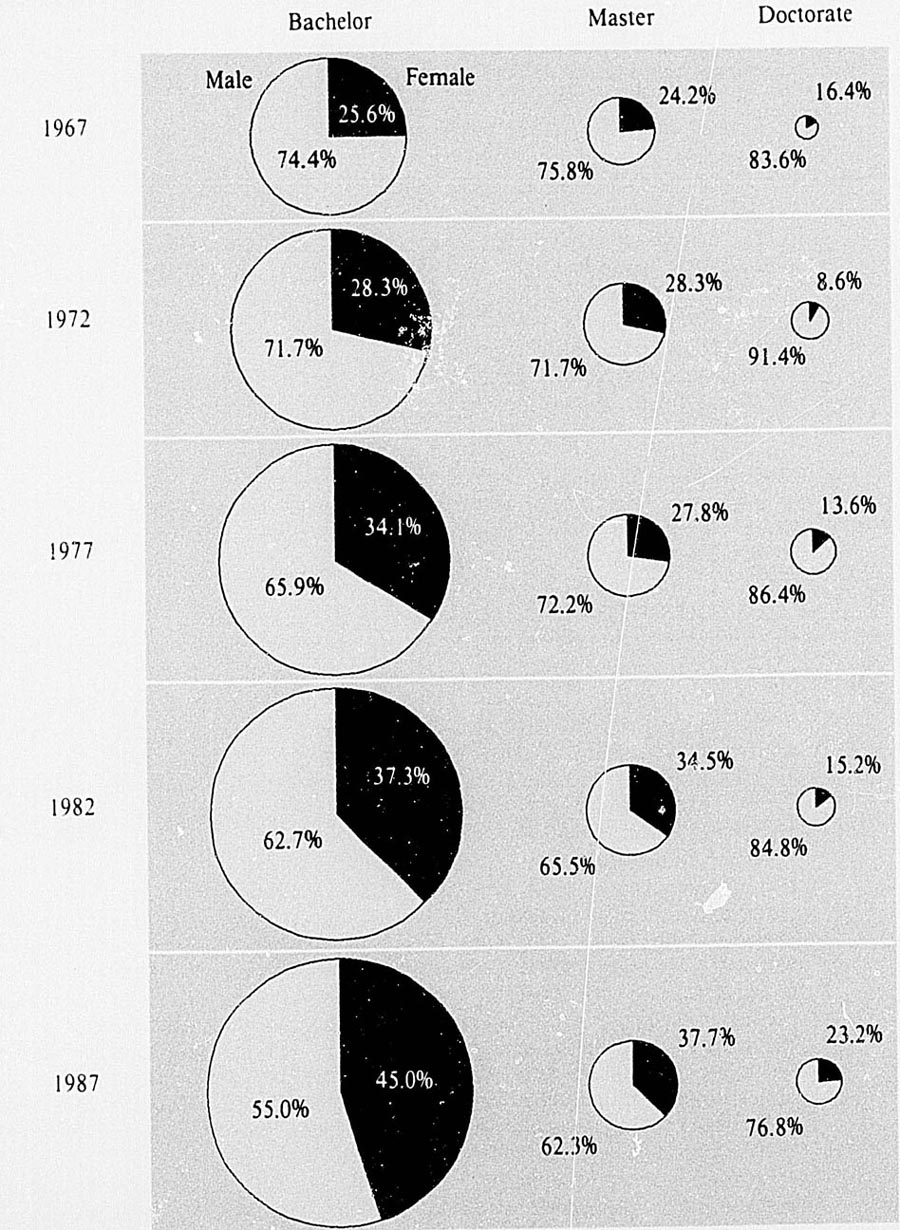

| University degrees awarded—selected years, 1967–87 | 360 |

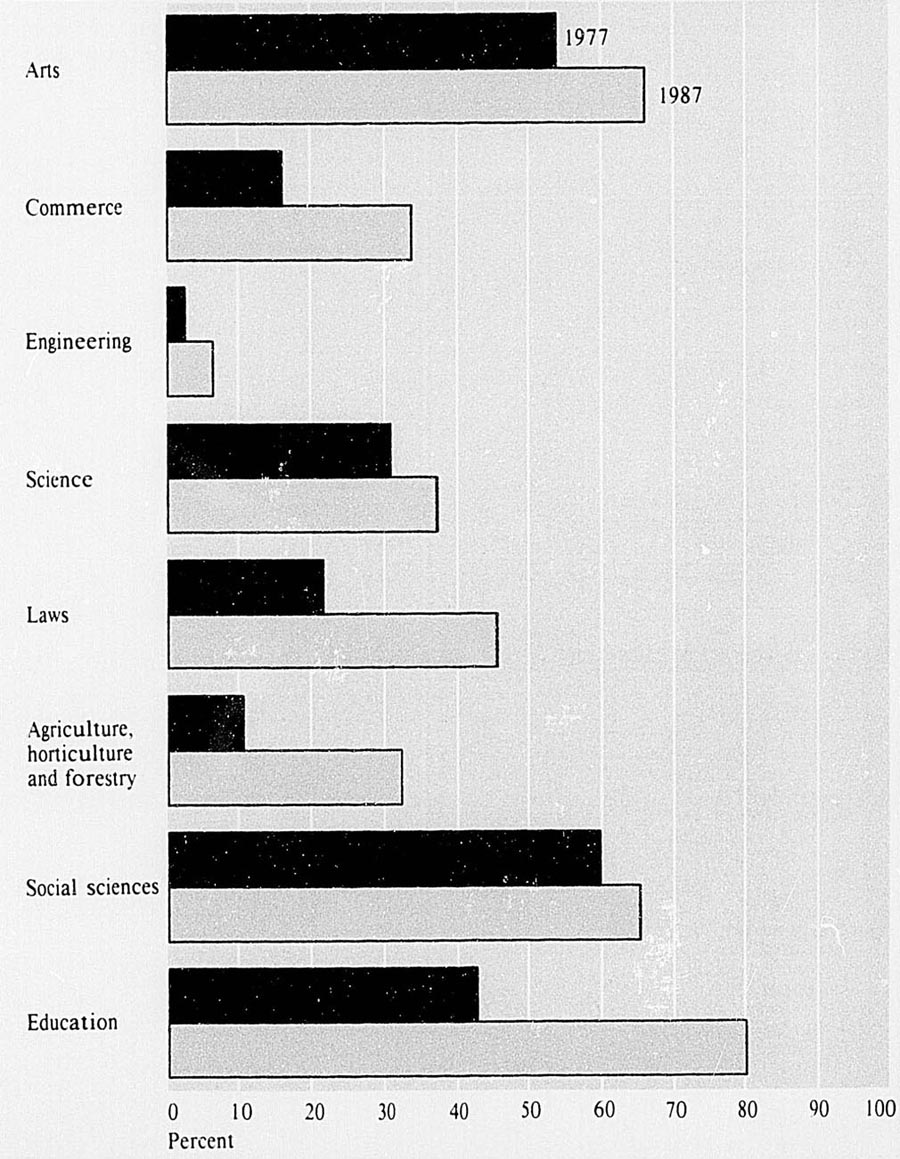

| Percentage of bachelor (incl. honours) degrees awarded to women in selected fields, 1977 and 1987 | 363 |

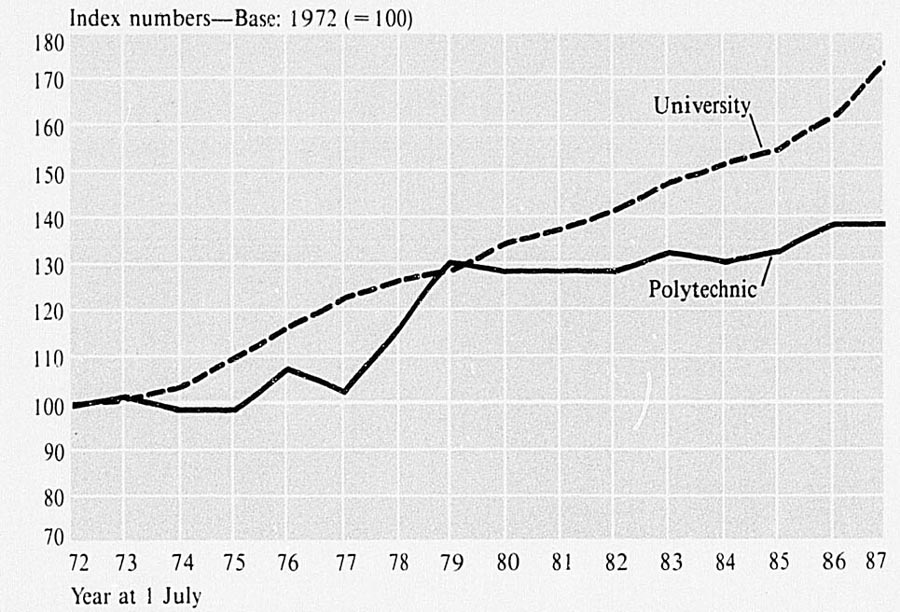

| Enrolment growth—tertiary | 366 |

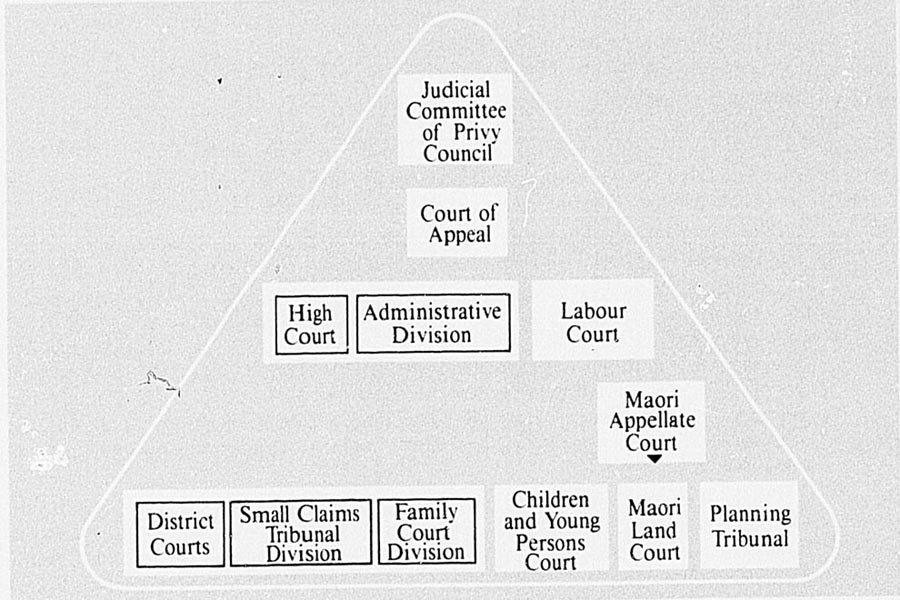

| Hierarchy of courts | 375 |

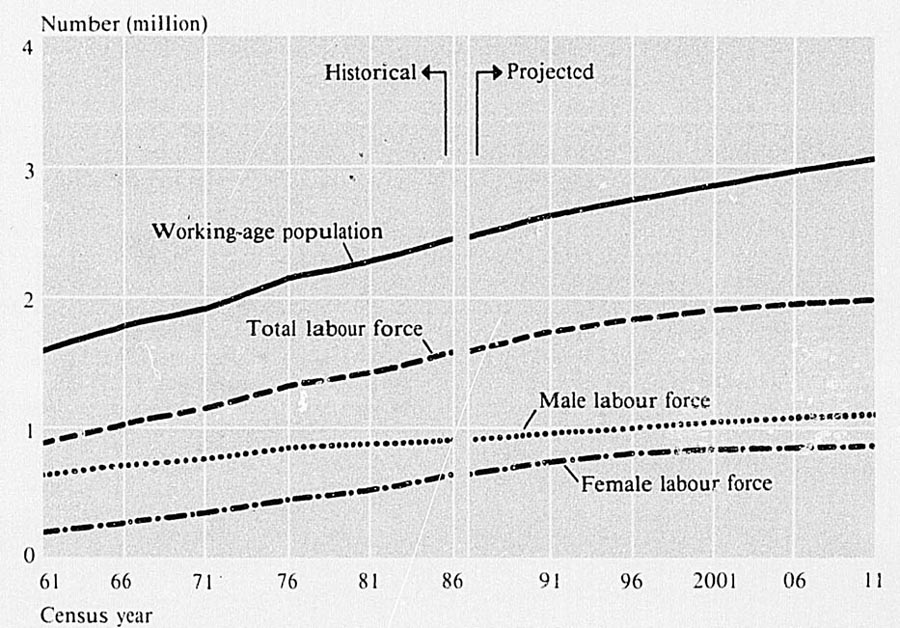

| Labour force—historical and projected by working-age and sex | 433 |

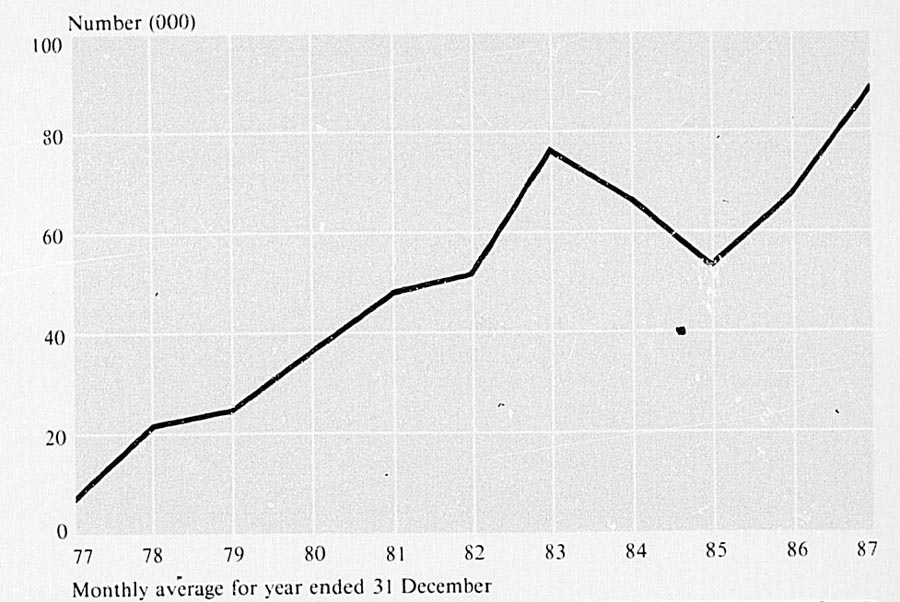

| Unemployment—registered unemployed including vacation workers | 443 |

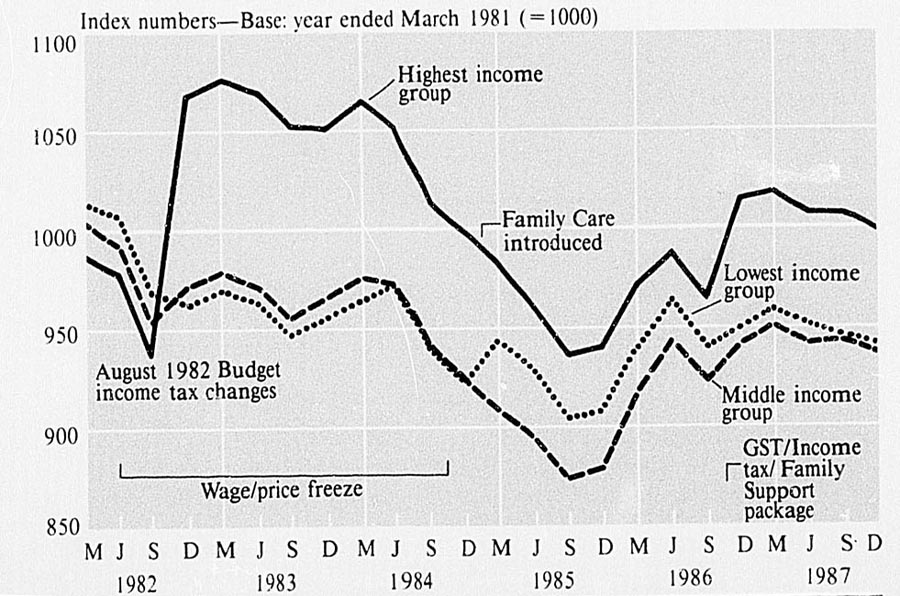

| Real disposable income indexes—full-time wage and salary earners | 450 |

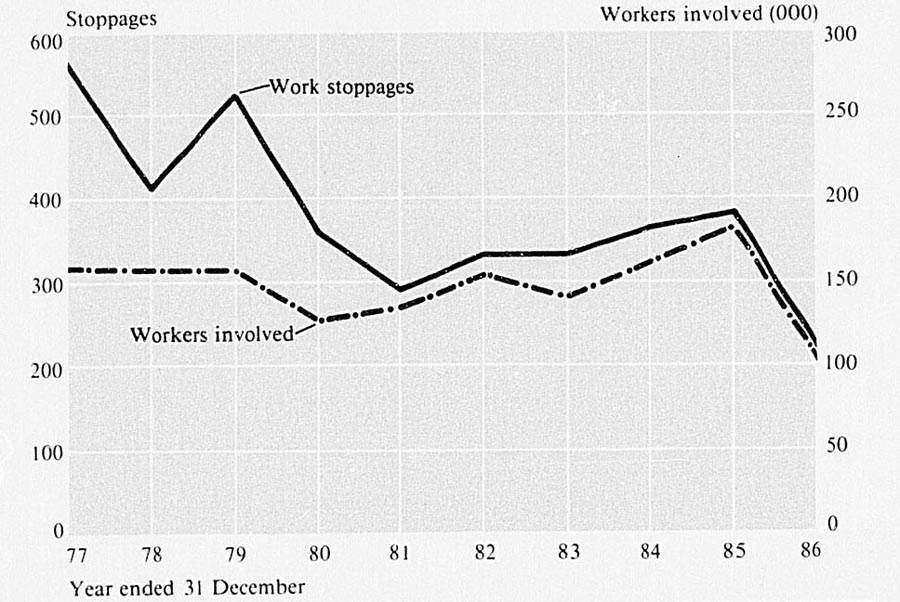

| Work stoppages—all industries | 460 |

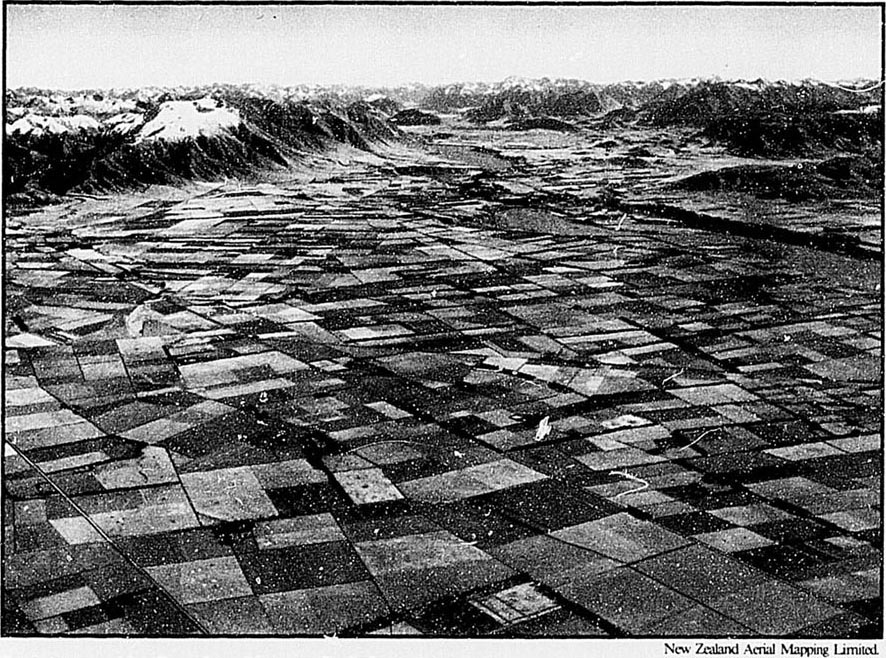

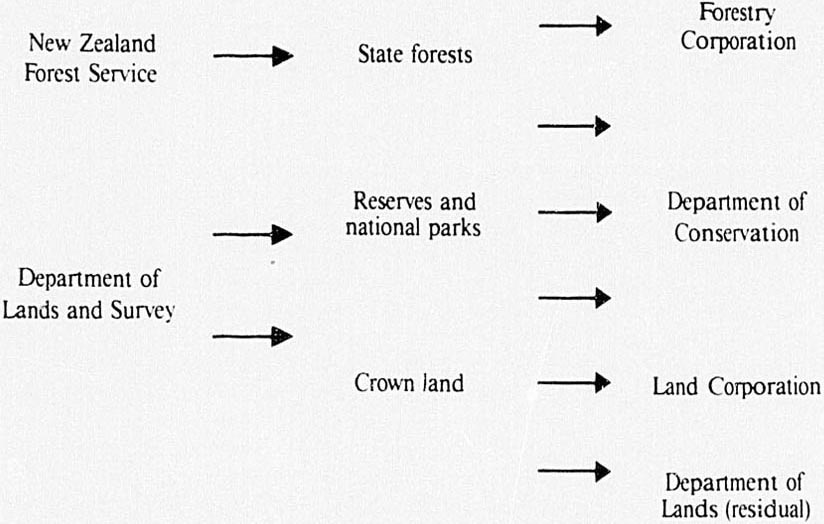

| Reallocation of public lands, 1987 | 496 |

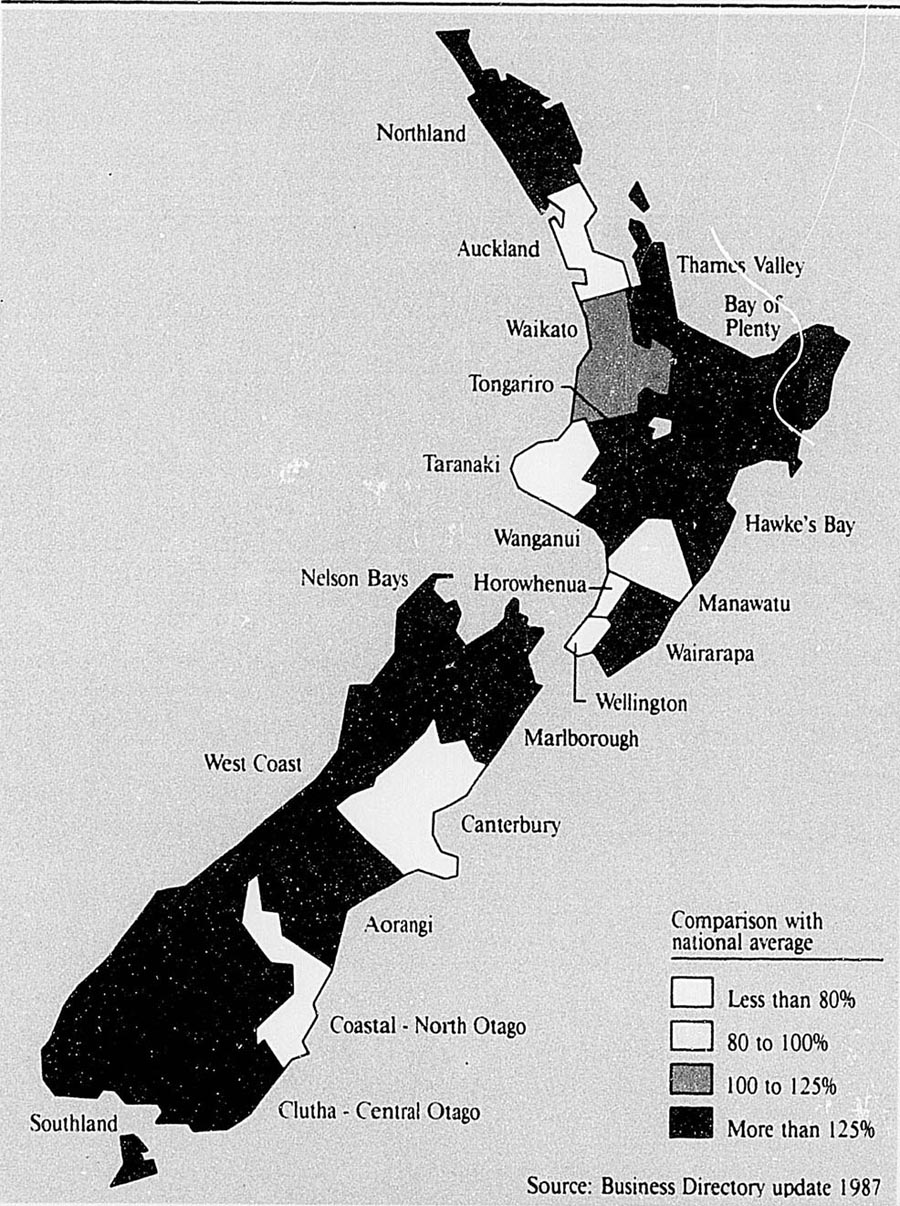

| Percentage of workforce employed in agricultural contracting, hunting, forestry and fishing | 521 |

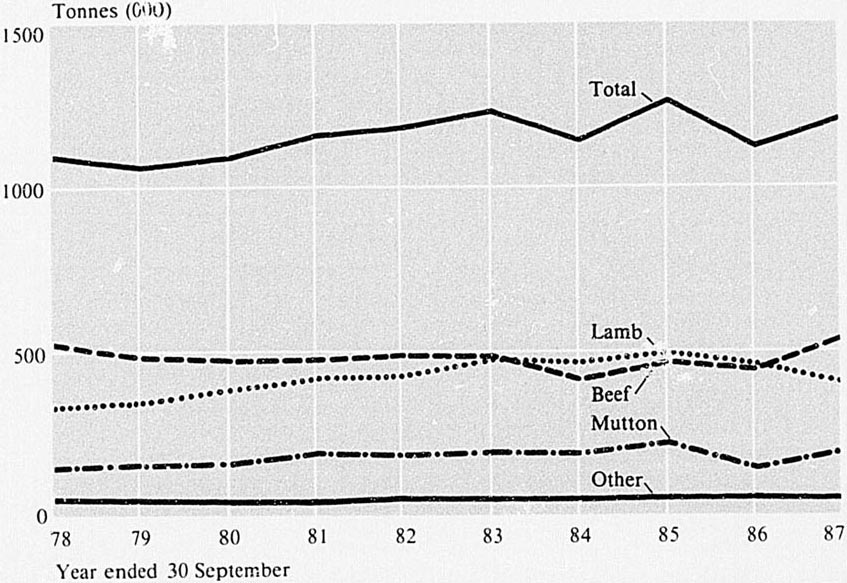

| Meat production—bone-in basis | 533 |

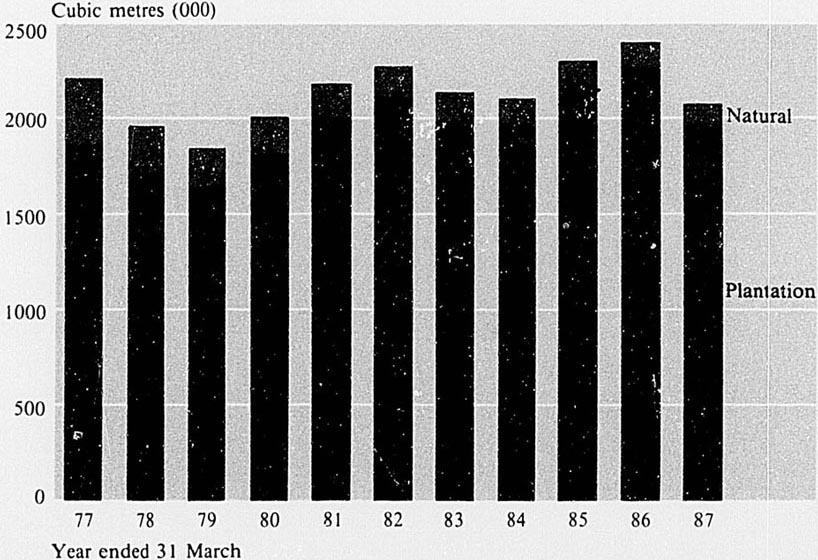

| Sawn timber production | 561 |

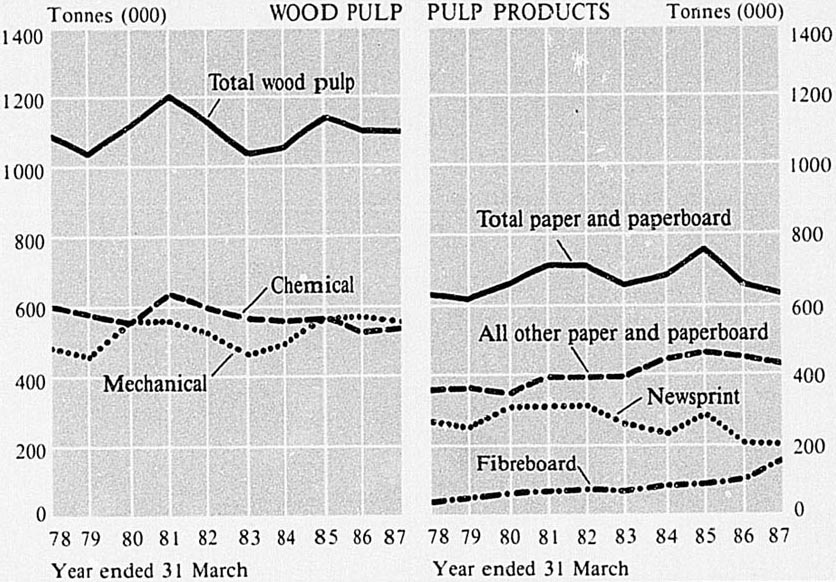

| Pulp and paper industry | 565 |

| Percentage of workforce employed in electricity, gas and water industry | 581 |

| Electricity generation | 587 |

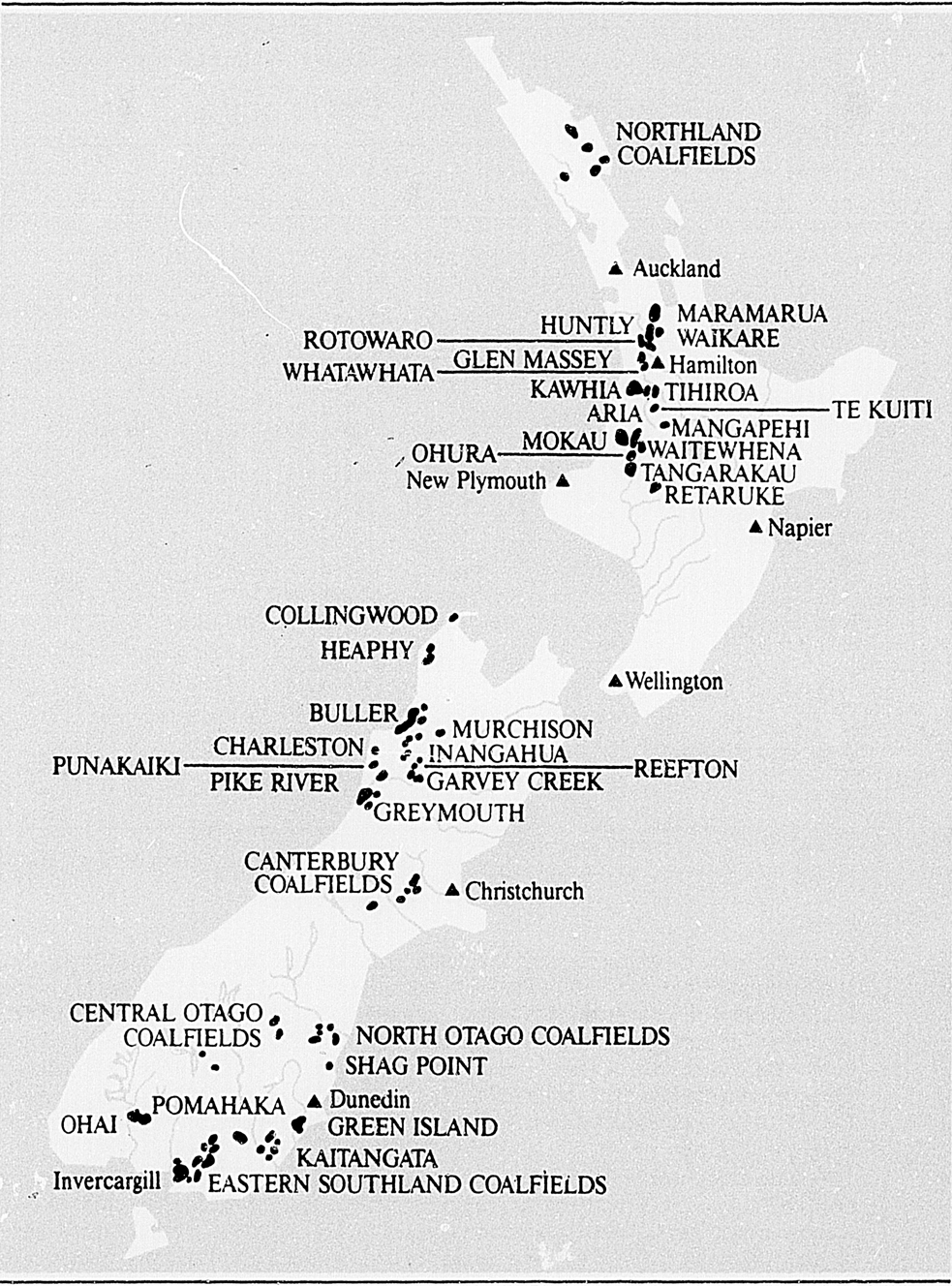

| Coalfields | 593 |

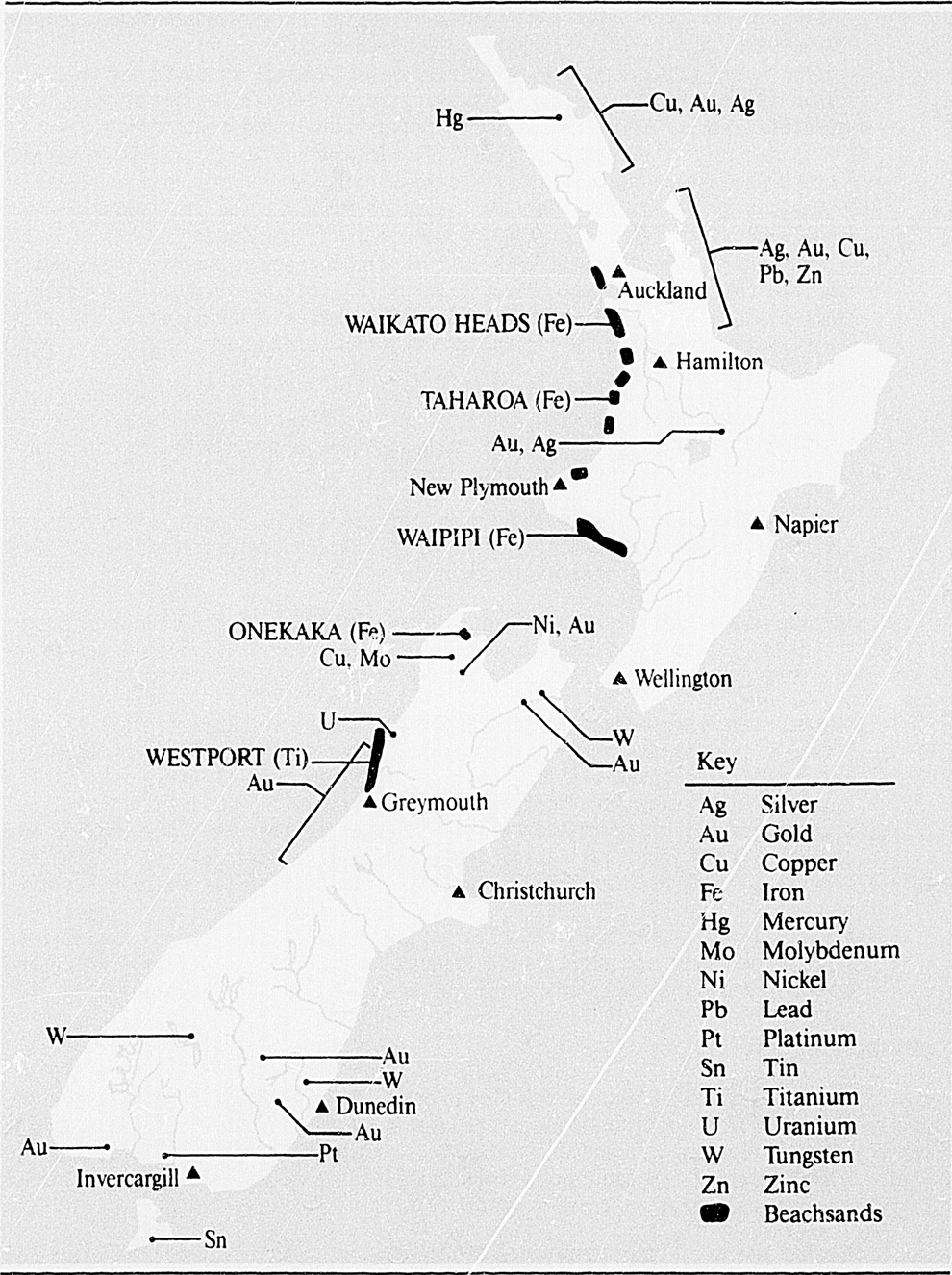

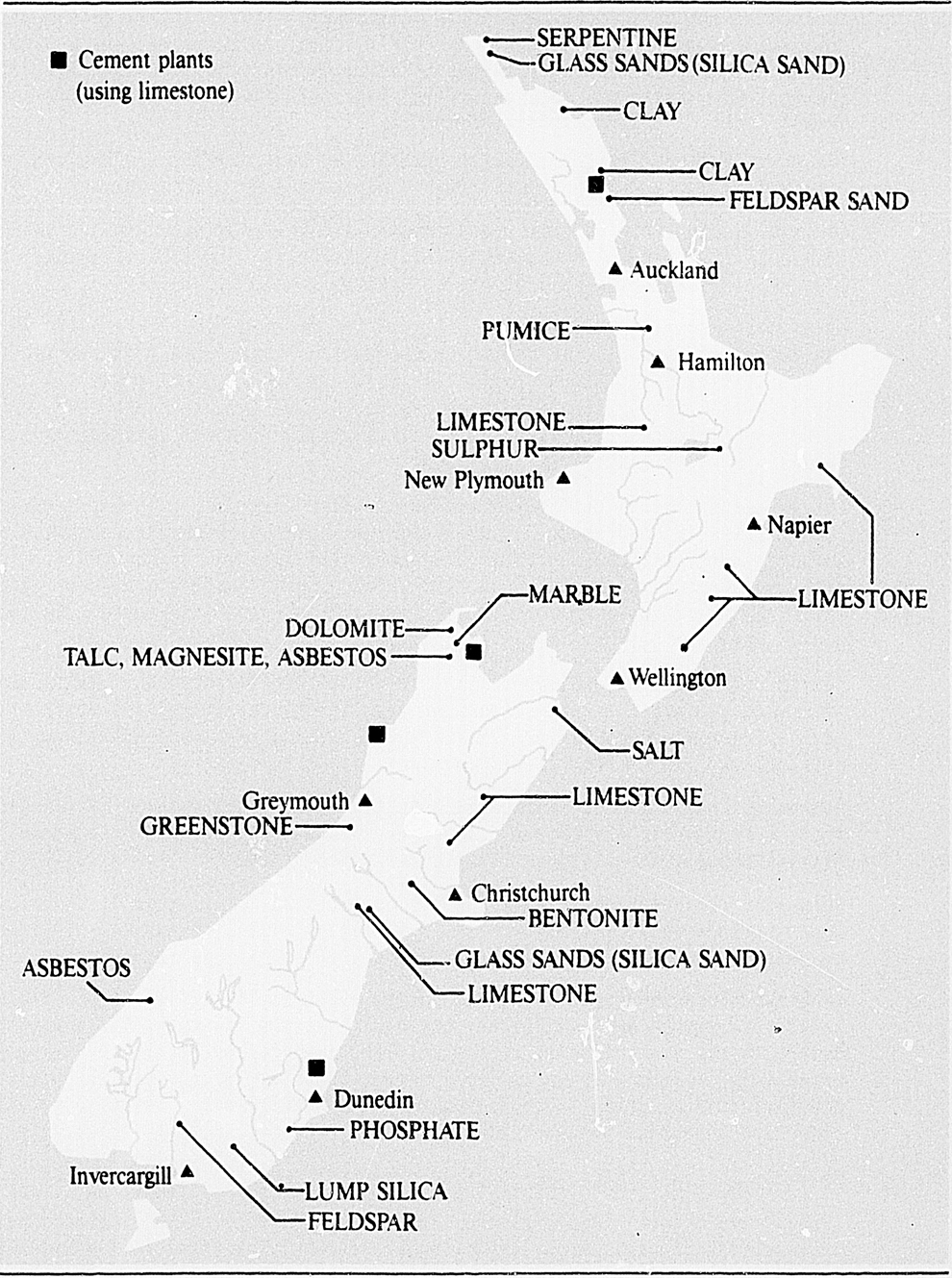

| Metal, mining and prospecting; past and present | 595 |

| Non-metallic minerals | 597 |

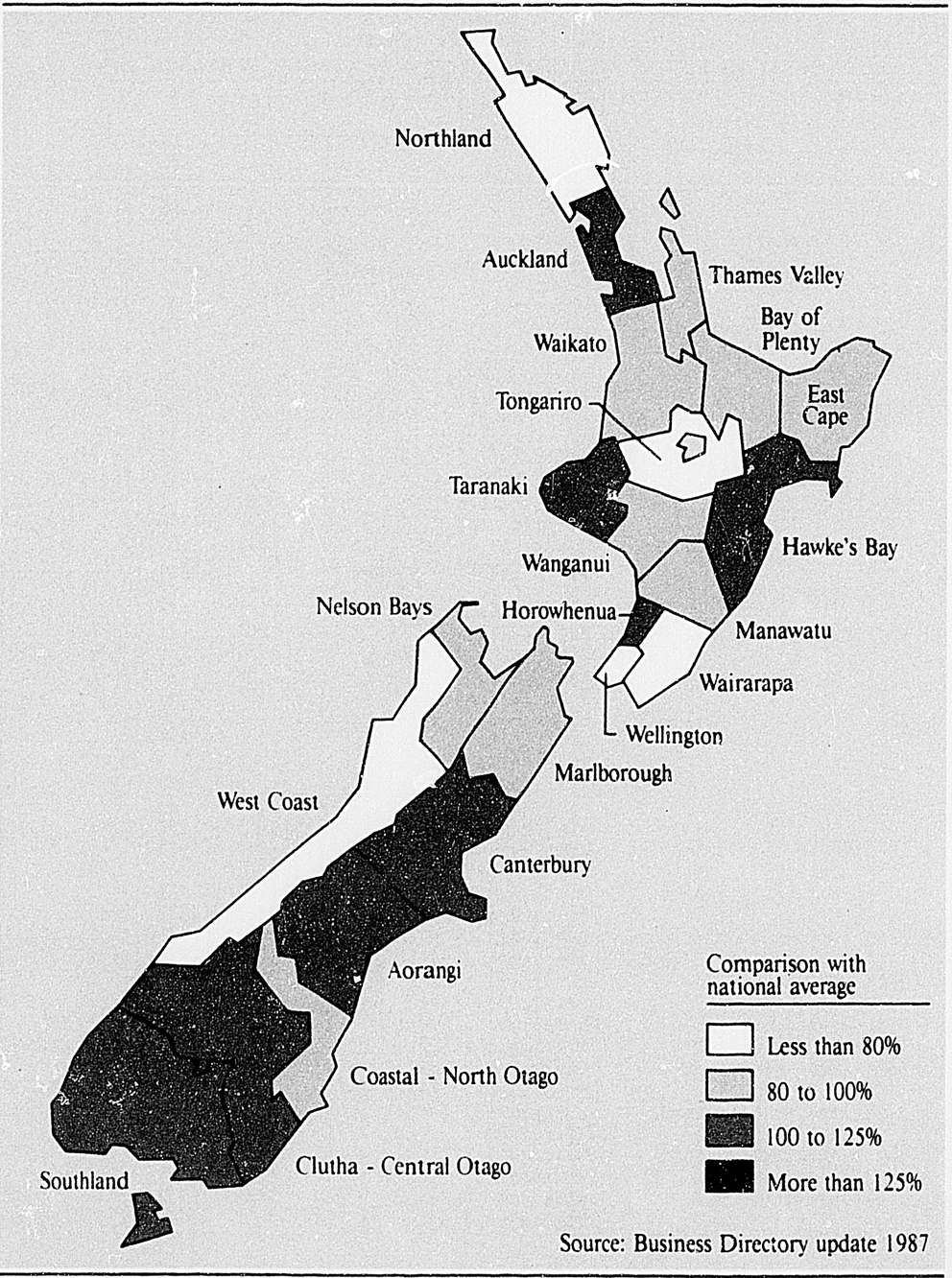

| Percentage of workforce employed in mining and quarrying | 599 |

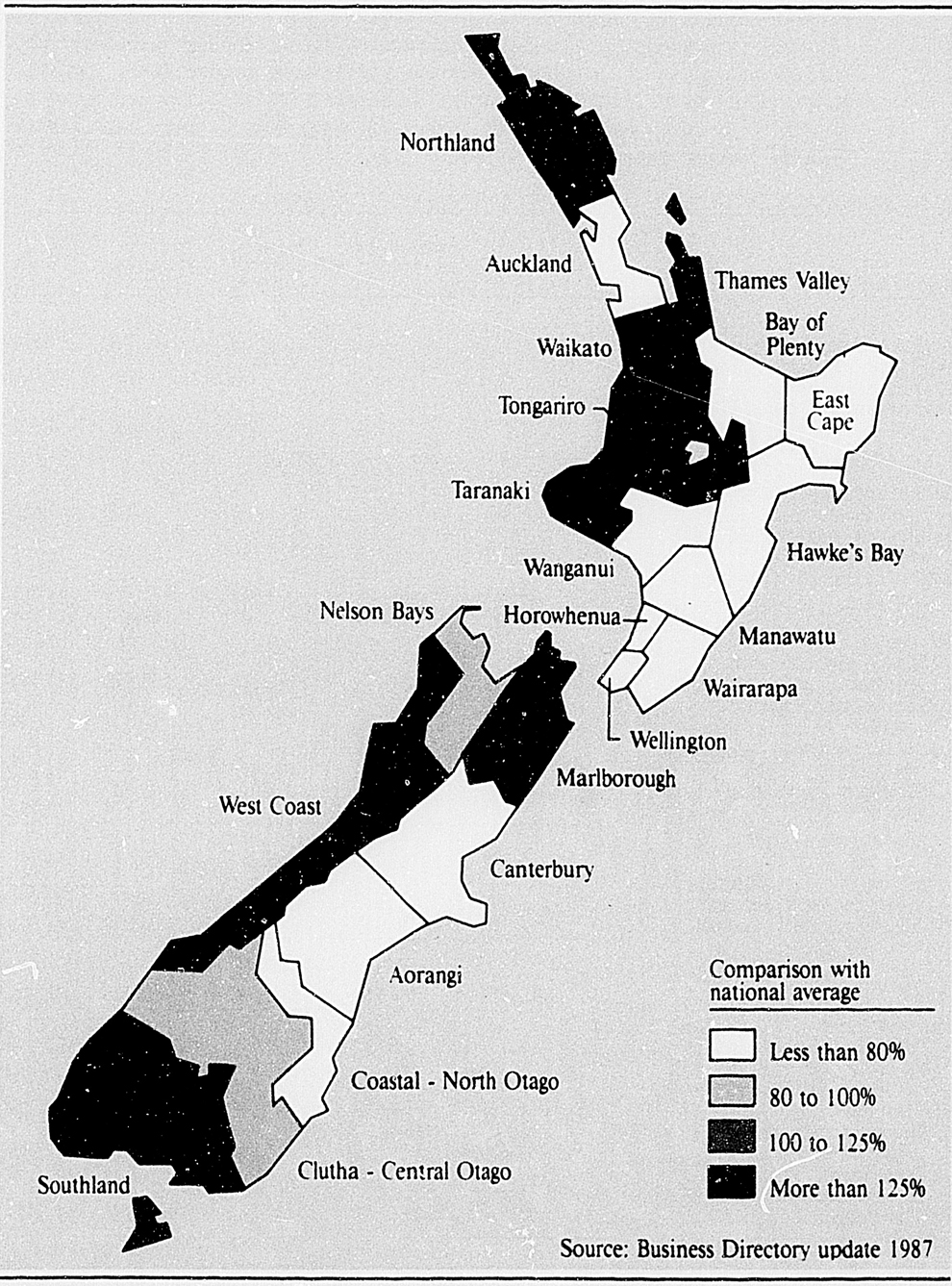

| Percentage of workforce employed in manufacturing | 608 |

| Building permits—new dwellings | 632 |

| Percentage of workforce employed in building and construction | 634 |

| Percentage of workforce employed in transport, storage and communication | 640 |

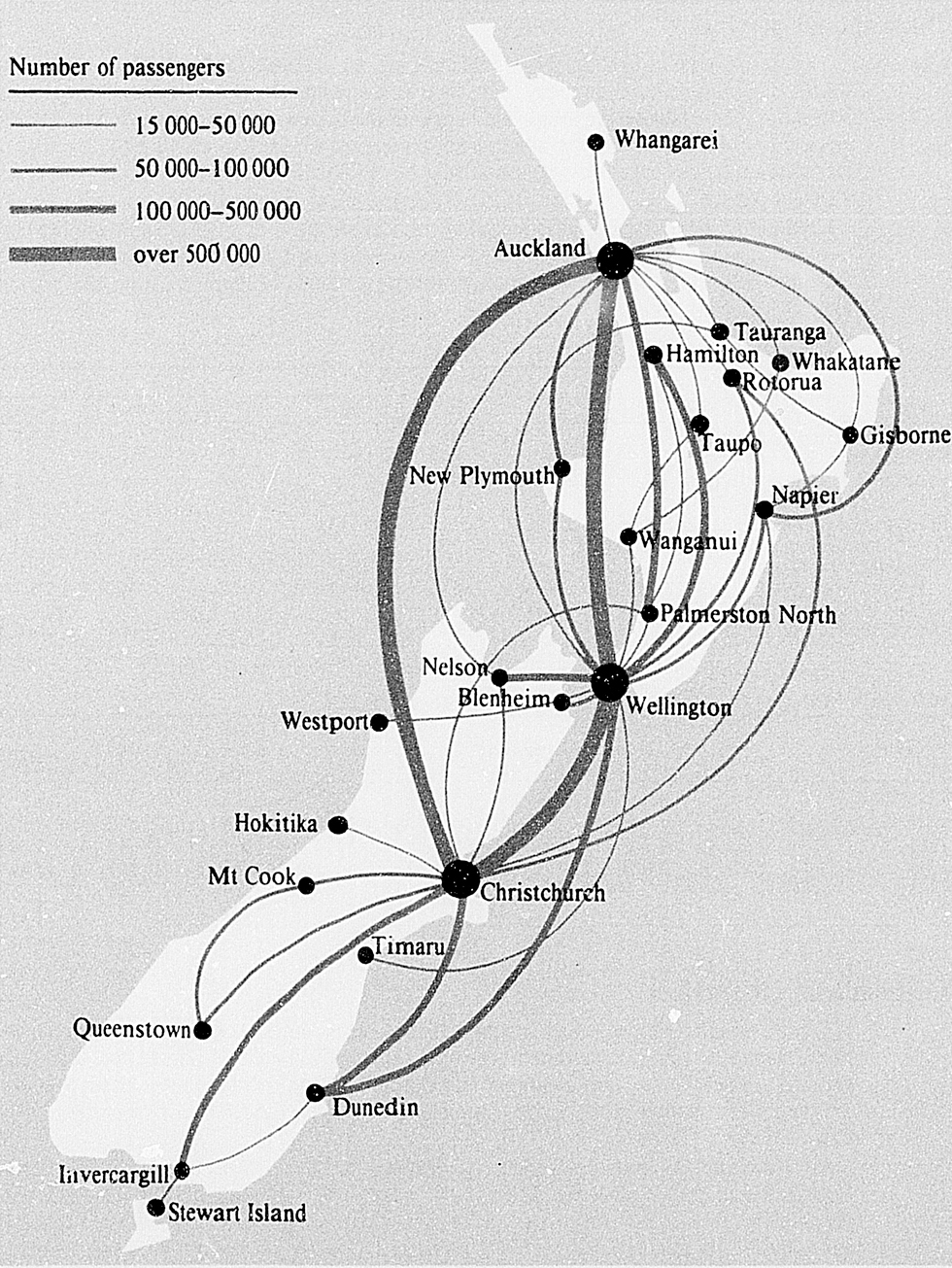

| Domestic air travel—passenger volumes, 1987 | 651 |

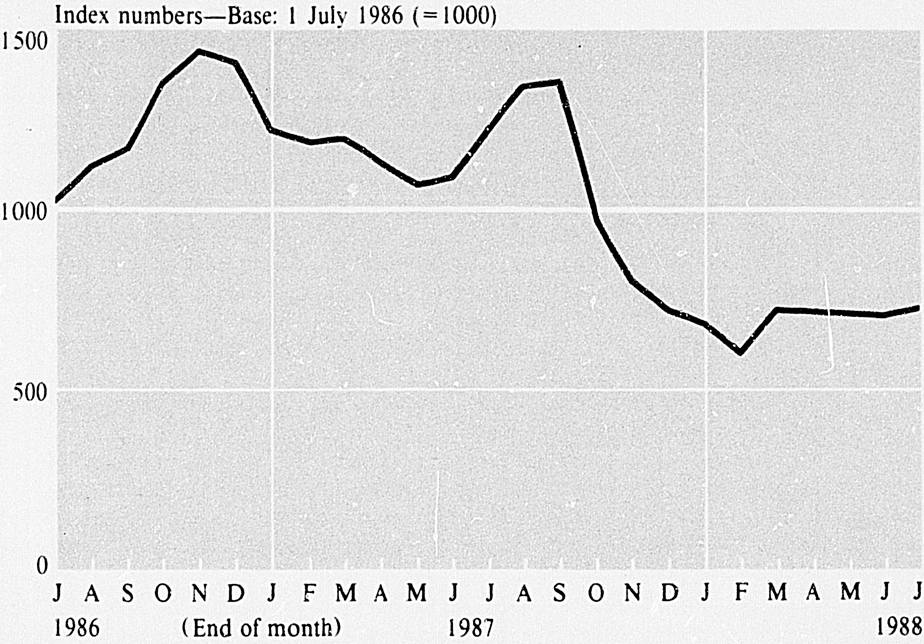

| Share prices—New Zealand Stock Exchange Gross Index | 687 |

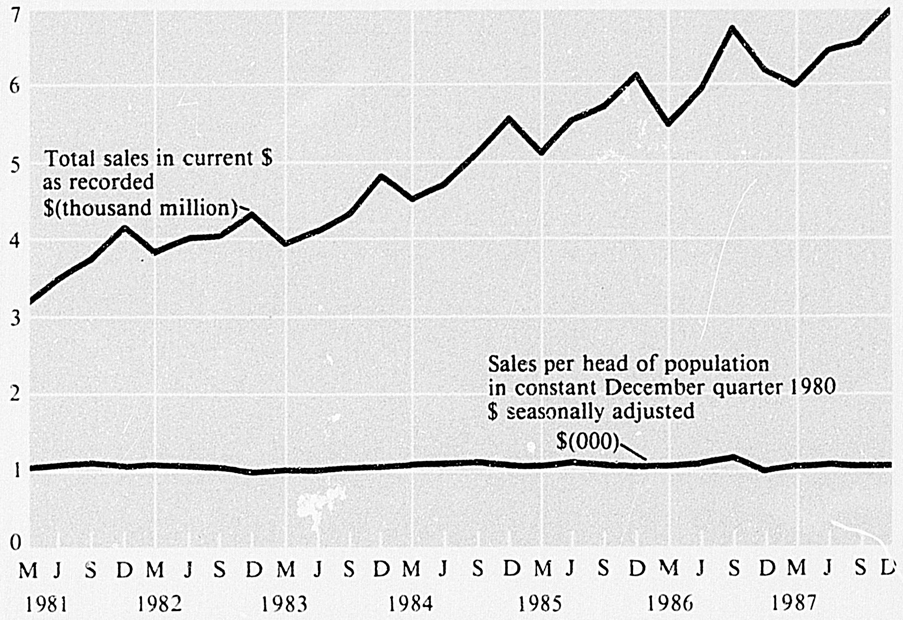

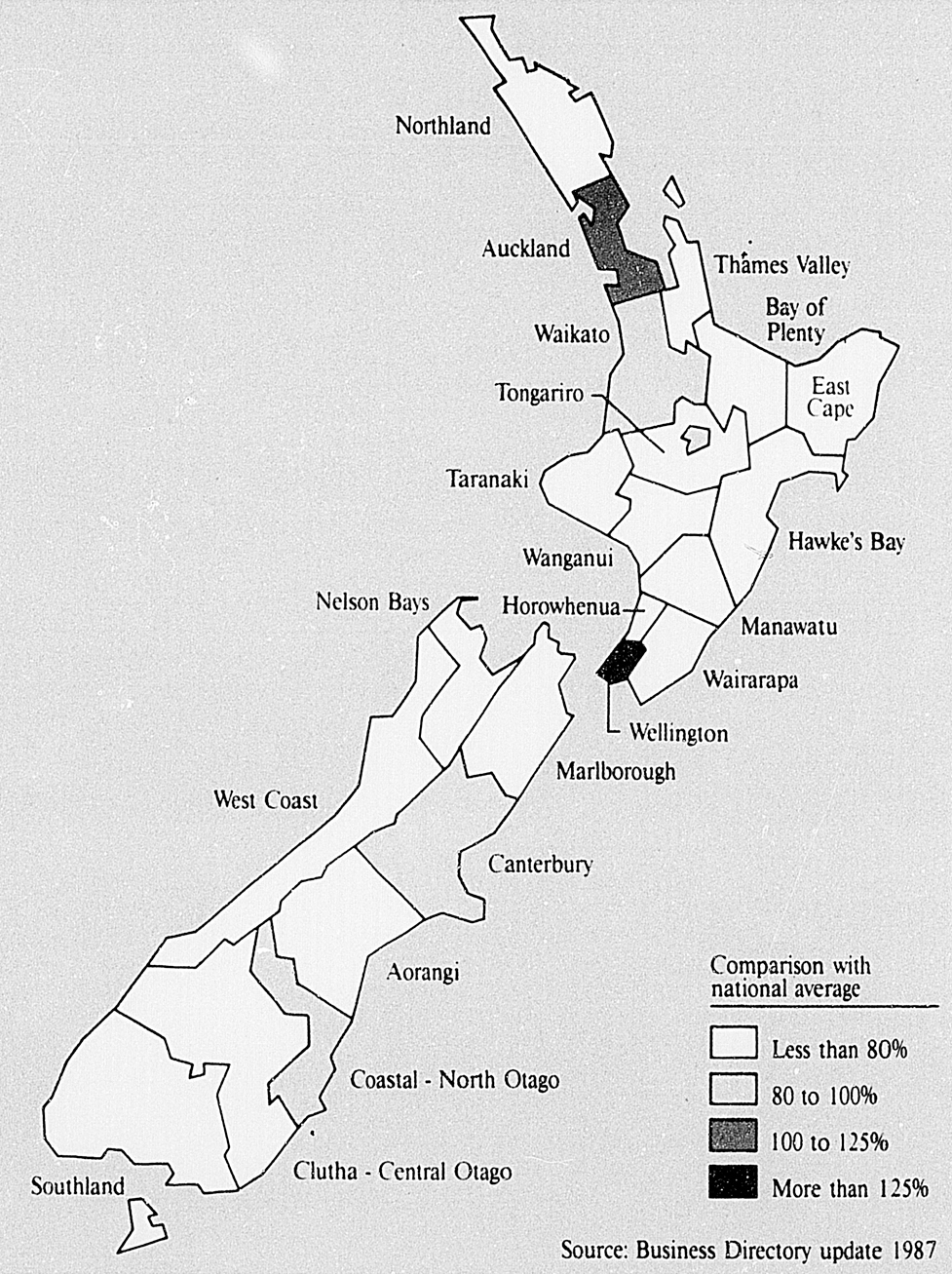

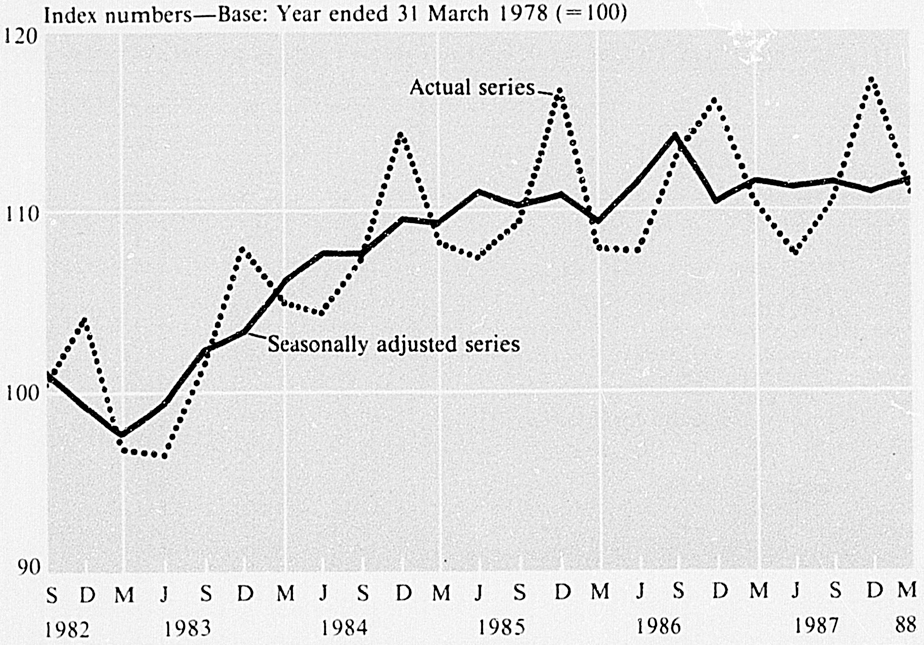

| Retail trade | 701 |

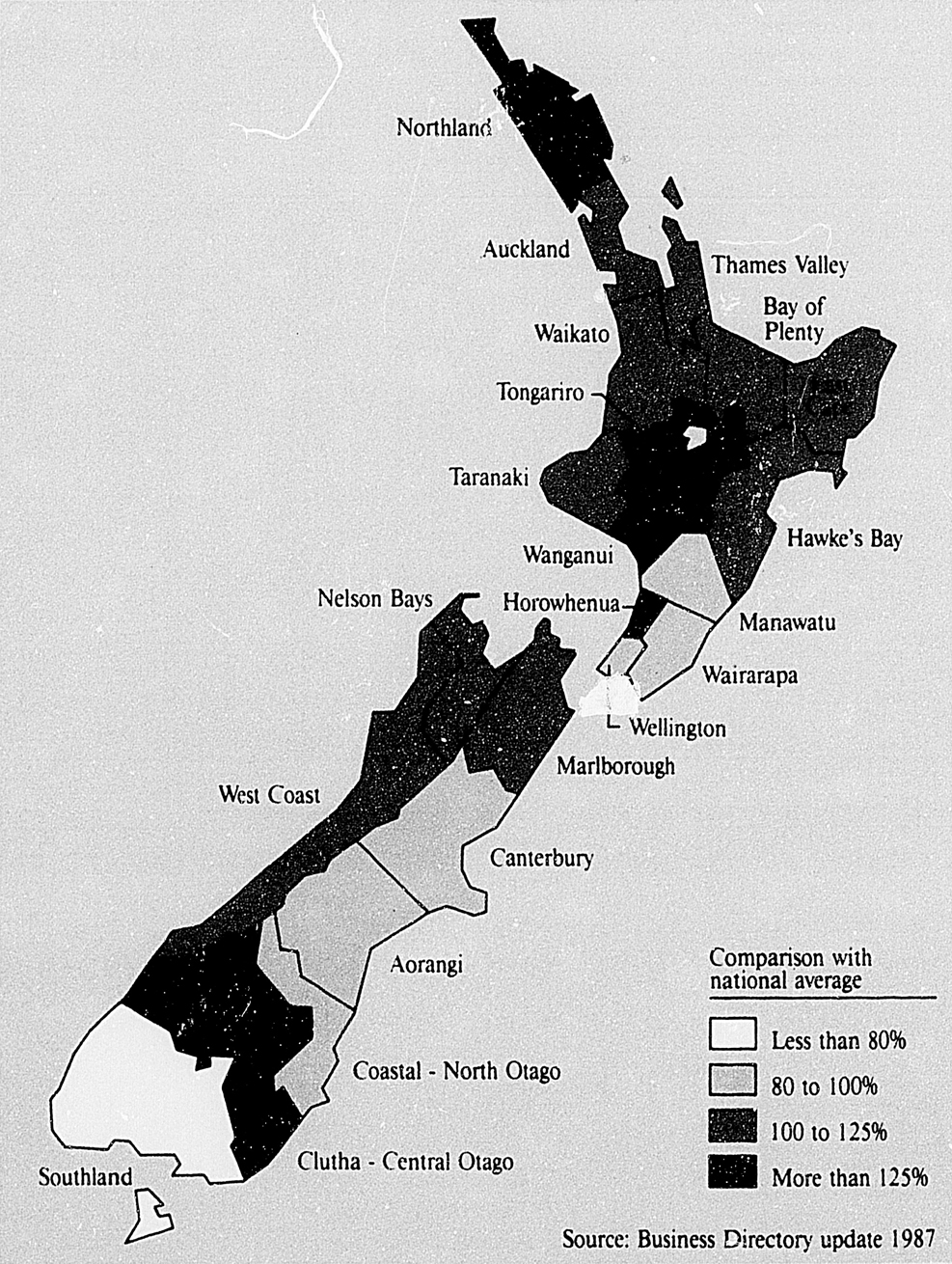

| Percentage of workforce employed in financing, insurance and real estate | 702 |

| Percentage of workforce employed in wholesale/retail trade, restaurants and hotels | 705 |

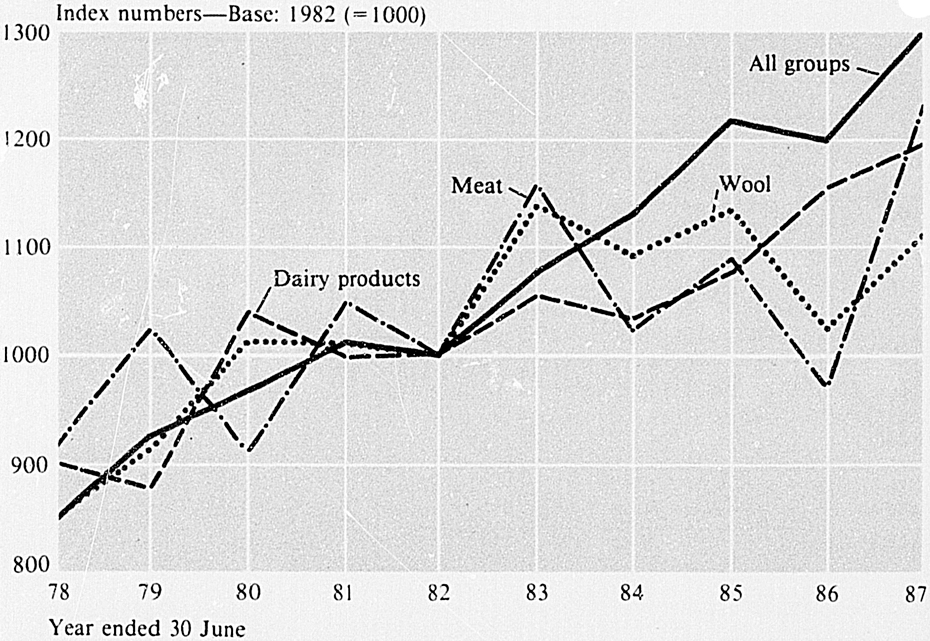

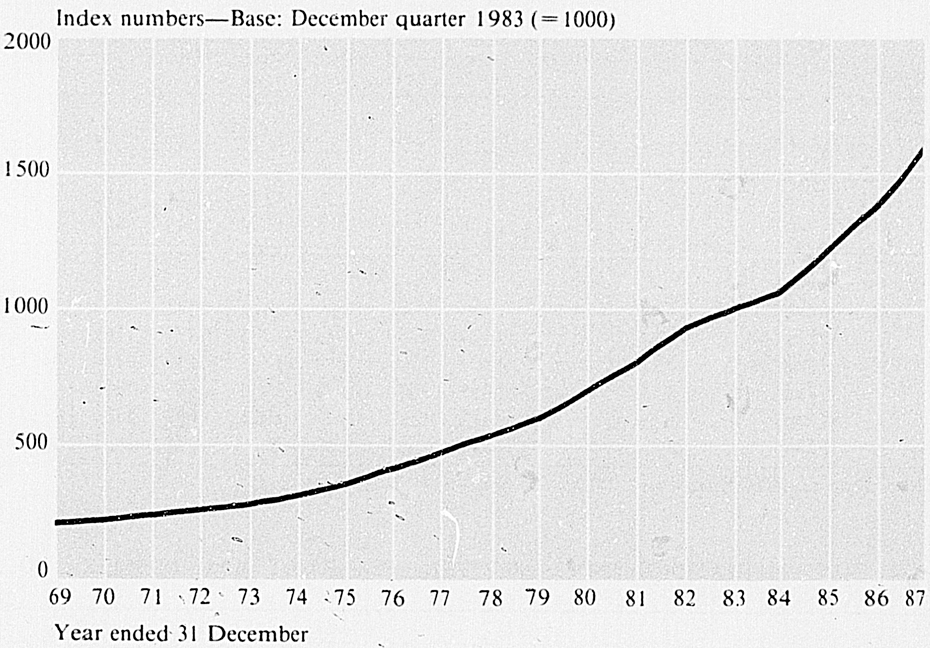

| Volume of exports | 723 |

| Trans-Tasman trade balance | 726 |

| Consumers Price Index—all groups annual average | 745 |

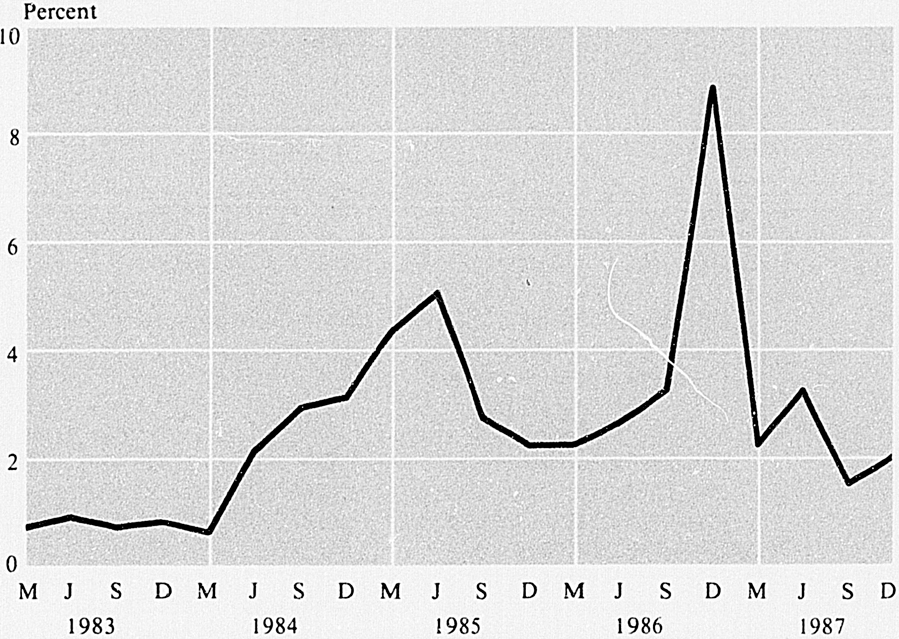

| Consumers Price Index—percentage change by quarter | 747 |

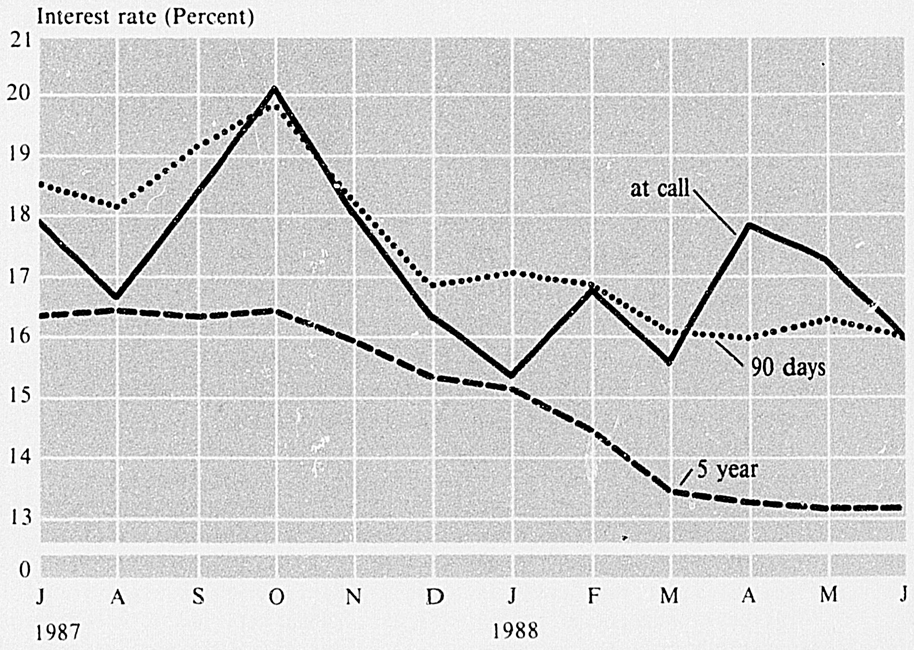

| Key market rates—monthly averages | 769 |

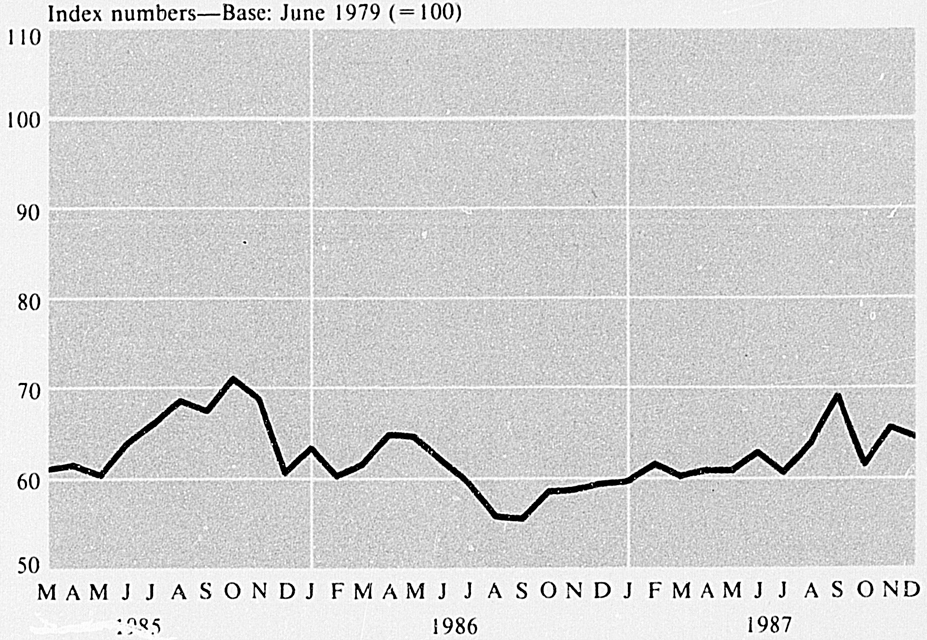

| Trade weighted exchange rate index | 771 |

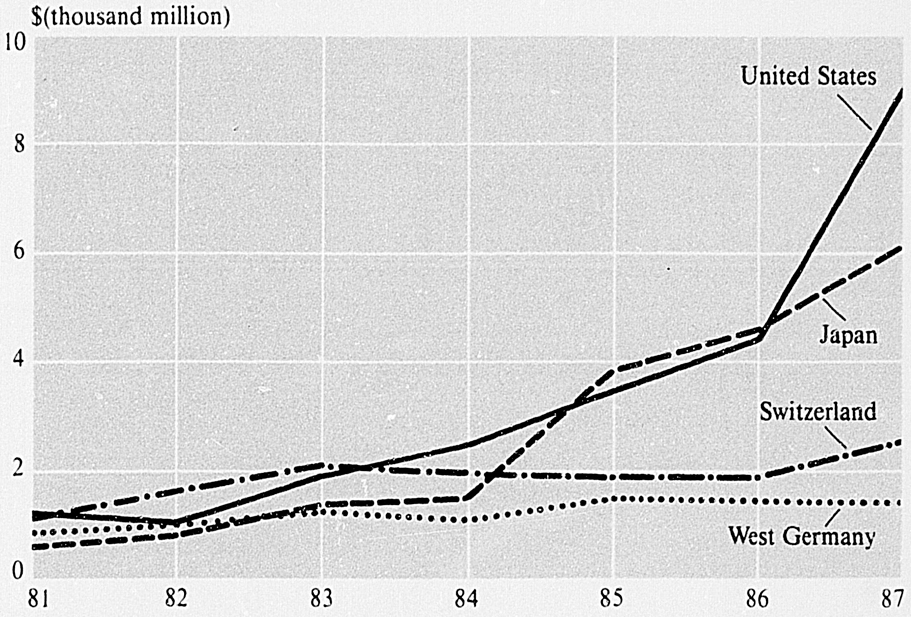

| Overseas debt—to selected countries | 795 |

| Index of total GDP—at constant prices | 820 |

Table of Contents

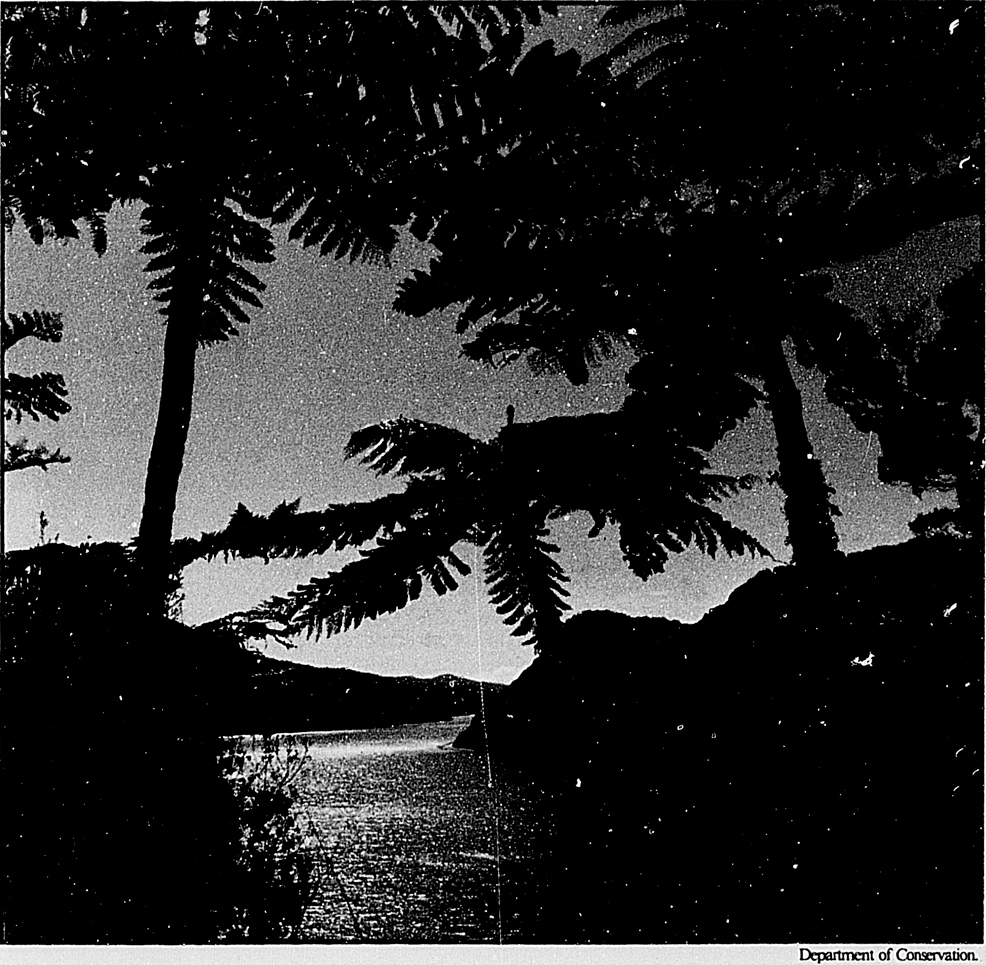

Marlborough Sounds.

New Zealand lies in the south-west Pacific Ocean and consists of two main, and a number of smaller islands, whose combined area of 268 000 square kilometres is similar to the size of Japan or the British Isles.

The main North and South Islands are separated by Cook Strait, which is relatively narrow. They lie on an axis running from north-east to south-west, except for the low-lying Northland peninsula. The administrative boundaries of New Zealand extend from 33 degrees to 53 degrees south latitude, and from 162 degrees east to 173 degrees west longitude. In addition to the main and nearby islands, New Zealand also includes the following small inhabited outlying islands: the Chatham Islands, 850 kilometres east of Christchurch; Raoul Island in the Kermadec Group, 930 kilometres north-east of the Bay of Islands; and Campbell Island, 590 kilometres south of Stewart Island. New Zealand also has jurisdiction over the territories of Tokelau and the Ross Dependency, which are described in chapter 4.

Table 1.1. LAND AREA OF NEW ZEALAND*

| Land area | Size |

|---|---|

* These figures were current at 1 April 1988, although new mapping techniques mean there are regular small adjustments. † Includes islands in territorial local authorities. ‡ Excluding islands in territorial local authorities. Source: Department of Survey and Land Information. | |

| sq. km. | |

| North Island† | 114,821 |

| South Island† | 149,463 |

| Offshore islands‡ | 833 |

| Stewart Island | 1,746 |

| Chatham Islands | 963 |

| Total | 267 844 |

New Zealand is more than 1600 kilometres long and 450 kilometres wide at its widest part, and has a long coastline for its area. The coast is very indented in places, providing many natural harbours.

New Zealand is also very mountainous, with less than a quarter of the land less than 200 metres above sea level. In the North Island the main ranges run generally south-west, parallel to the coast, from East Cape to Cook Strait, with further ranges and four volcanic peaks to the north-west. The South Island is much more mountainous than the North Island. A massive mountain chain, the Southern Alps, runs almost the length of the island. There are many outlying ranges to the Southern Alps in the north, and the south-west of the South Island. There are at least 223 named peaks higher than 2300 metres. There are also 360 glaciers in the Southern Alps. The largest are, on the east, the Tasman (length 29 kilometres), Murchison (17 kilometres), Mueller (13 kilometres), Godley (13 kilometres) and the Hooker (11 kilometres), and, on the west, the Fox (15 kilometres) and the Franz Josef (13 kilometres).

Table 1.2. PRINCIPAL MOUNTAINS

| Mountain or peak | Height |

|---|---|

* Since 1986 both the Maori and European names of this mountain have had official recognition. † Peaks over 3000 metres. Source: Department of Survey and Land Information. | |

| metres | |

| North Island— | |

| Ruapehu | 2,797 |

| Taranaki or Egmont* | 2,518 |

| Ngauruhoe | 2,290 |

| Tongariro | 1,968 |

| South Island†— | |

| Southern Alps— | |

| Cook | 3,764 |

| Tasman | 3,497 |

| Dampier | 3,440 |

| Silberhorn | 3,279 |

| Lendenfeldt | 3,201 |

| Mt Hicks (St David's Dome) | 3,183 |

| Torres | 3,163 |

| Teichelmann | 3,160 |

| Sefton | 3,157 |

| Malte Brun | 3,155 |

| Haast | 3,138 |

| Elie de Beaumont | 3,117 |

| Douglas | 3,085 |

| La Perouse | 3,079 |

| Heidinger | 3,066 |

| Minarets | 3,055 |

| Aspiring | 3,030 |

| Glacier Peak | 3,007 |

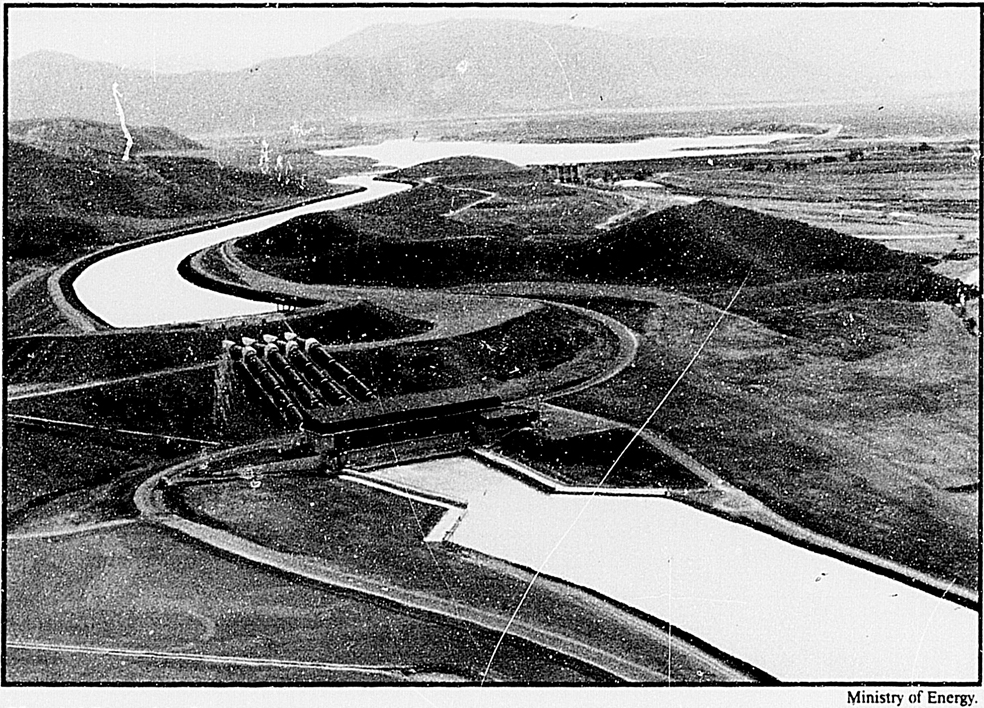

New Zealand's rivers are mainly swift and difficult to navigate. They are important as sources of hydro-electric power and many artificial lakes have been created as part of major hydro-electric schemes. New Zealand also has numerous natural lakes of great scenic beauty.

Table 1.3. PRINCIPAL RIVERS*

| River | Length |

|---|---|

* Over 150 kilometres in length from the mouth to the farthest point in the river system irrespective of name, including estimated courses through lakes. Source: Department of Survey and Land Information. | |

| km | |

| North Island— | |

| Flowing into the Pacific Ocean— | |

| Rangitaiki | 193 |

| Waihou | 175 |

| Mohaka | 172 |

| Ngaruroro | 154 |

| Flowing into the Tasman Sea— | |

| Waikato | 425 |

| Wanganui | 290 |

| Rangitikei | 241 |

| Manawatu | 182 |

| Whangaehu | 161 |

| Mokau | 158 |

| South Island— | |

| Flowing into Cook Strait– | |

| Wairau | 169 |

| Flowing into the Pacific Ocean— | |

| Clutha | 322 |

| Taieri | 288 |

| Clarence | 209 |

| Waitaki | 209 |

| Waiau | 169 |

| Waimakariri | 161 |

| Flowing into Foveaux Strait— | |

| Mataura | 240 |

| Waiau | 217 |

| Oreti | 203 |

| Flowing into the Tasman Sea— | |

| Buller | 177 |

Table 1.4. PRINCIPAL LAKES*

| Lake | Area |

|---|---|

* Over 20 square kilometres in area. Source: Department of Survey and Land Information. | |

| sq. km | |

| North Island— | |

| Taupo | 606 |

| Rotorua | 80 |

| Wairarapa | 80 |

| Waikaremoana | 54 |

| Tarawera | 36 |

| Rotoiti | 34 |

| South Island— | |

| Te Anau | 344 |

| Wakatipu | 293 |

| Wanaka | 193 |

| Ellesmere | 181 |

| Pukaki | 169 |

| Manapouri | 142 |

| Hawea | 141 |

| Tekapo | 88 |

| Benmore (artificial) | 75 |

| Hauroko | 71 |

| Ohau | 61 |

| Poteriteri | 47 |

| Brunner | 39 |

| Coleridge | 36 |

| Monowai | 31 |

| Aviemore (artificial) | 29 |

| Rotoroa | 23 |

| Mahinerangi (artificial) | 21 |

New Zealand is in an area of the world characterised by active volcanoes and frequent earthquakes. The ‘ring of fire’, as this area is known, forms a belt that surrounds the Pacific Ocean and is the surface expression of a series of boundaries between the plates that make up the earth's crust. Plate tectonics is a theory used to explain the fundamental geological features of the earth. According to the theory the crust of the earth is made up of a series of plates, rather like a jigsaw puzzle. Although these surface plates are rigid, the rocks of the underlying layer of the earth, its upper mantle, are partially molten. This provides the convection mechanism for movement of the overlying plates. Over millions of years these plates have moved in relation to each other, colliding together, pulling apart, or sometimes sliding past each other. The boundary between the Indian-Australian plate and the Pacific plate runs through New Zealand, and the processes resulting from their collision have had a profound effect on New Zealand's geology. When two plates collide, one is pushed beneath the other in a process known as subduction. Zones of subduction are defined by two deep sea trenches to the north and south of New Zealand, which are connected by the Alpine Fault. The size, shape and geology of New Zealand reflects the long process of construction and deformation along this plate boundary.

The interplay of earth movements and erosion has created the sedimentary rocks that cover almost three-quarters of New Zealand. Erosion of land produced sand, mud, gravel and other debris which was carried out to sea, where it accumulated in great thicknesses to form rocks such as sandstone, mudstone, greywacke and conglomerate. The shells and skeletons of sea creatures also accumulated and formed thick layers of limestone. Most sedimentary rocks are formed in near horizontal layers called strata. Earth movements later raised the rocks above the sea to form land, and the strata were in many places tilted and folded by pressure. Seas advanced and retreated over the New Zealand area many times and the sedimentary rocks represent almost every geological period since the Cambrian (see time scale). Their age is revealed by the fossils they contain or may be determined by various radiometric techniques.

As well as the sedimentary rocks of various ages, New Zealand incorporates in its complex structure metamorphic rocks (schist, gneiss and marble), and intrusive igneous rocks (granite, gabbro, diorite and serpentine). Many of these metamorphic and intrusive igneous rocks are hundreds of millions of years old.

Intrusive rocks are generally considered to have entered the outer crust in a molten state, often during periods of mountain building. Some may, however, result from the intense metamorphism (melting) of pre-existing sediments. Intrusive rocks contain large crystals and have a coarse-grained texture.

Metamorphic rocks are formed when previously existing rocks are subjected to high temperatures and pressures while buried deep within the earth's crust. During metamorphism new minerals and structures develop within a rock due to the great temperatures and pressures. Such metamorphism often takes place during relatively short periods of mountain building.

Volcanic rocks (basalt, andesite, rhyolite and ignimbrite), are the products of many volcanic eruptions that have characterised New Zealand's geological history. The most recognisable volcanoes in New Zealand now occur in the North Island, where a number are active. They include those in Tongariro National Park, White Island and Mount Tarawera. Others such as Mount Taranaki (or Egmont), and Rangitoto may be considered dormant at present although they are still regarded as significant hazards. Sporadic episodes of volcanic activity have also occurred in the South Island with Timaru, Lyttelton, Oamaru and Dunedin all having basaltic volcanoes less than 13 million years old.

The oldest rocks in New Zealand are found in Nelson, Westland and Fiordland. They were formed in the Paleozoic era about 570 million years ago, but some in Westland may be older. They include thick sedimentary rocks which suggest that to yield the great volume of sediments a large landmass existed nearby at that time, although so far little has been deduced about its shape or position.

The history of the later part of the Paleozoic era, and the Mesozoic era, is rather better understood. For a vast span of time from the Carboniferous period, probably until the early Cretaceous period, an extensive depositional basin occupied the New Zealand region. At first, during much of the late Paleozoic, huge quantities of submarine lava and volcanic ash were included in the materials that accumulated. In the later Permian and Mesozoic times sediments were mainly sand and mud, probably derived from some landmass west of present New Zealand. These rocks have been compacted into hard greywacke (a type of sandstone), and argillite (hard, dark mudstone).

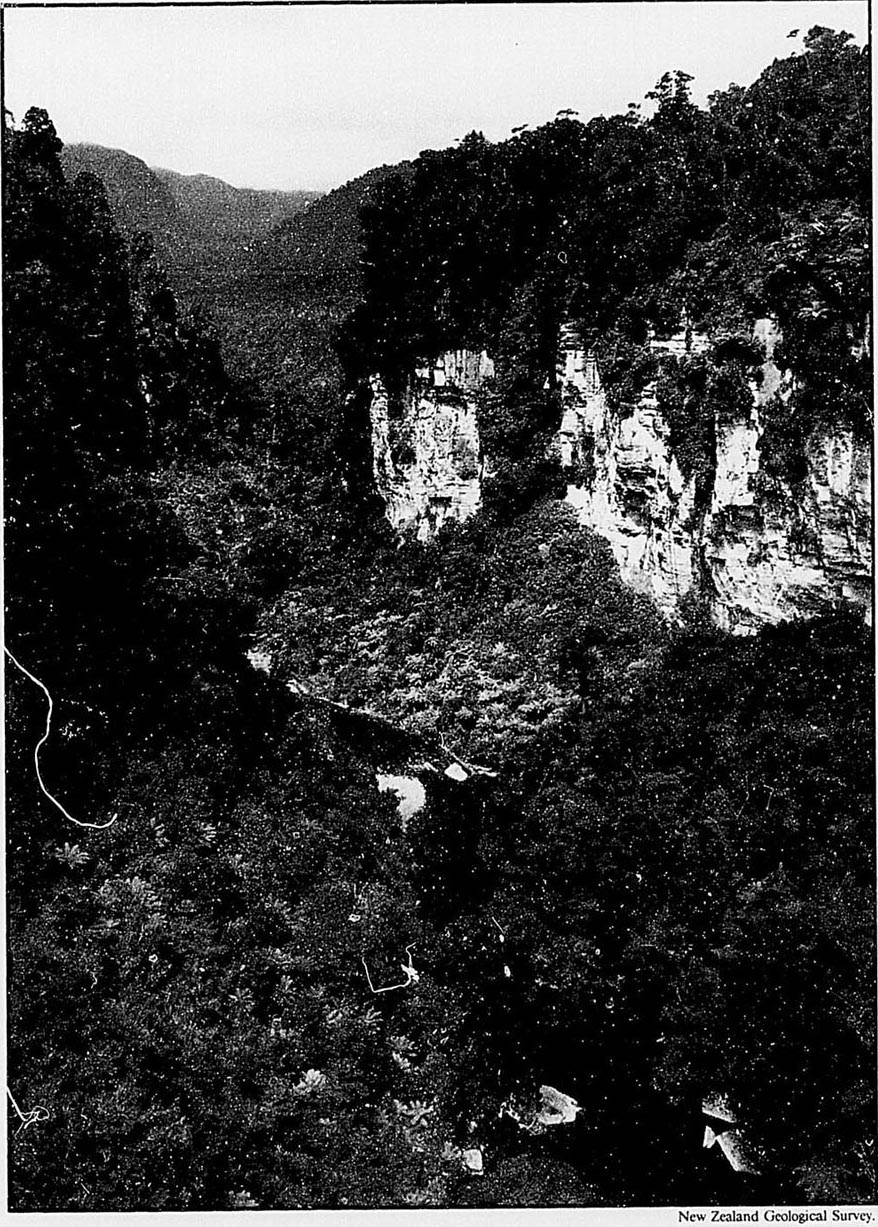

In the early Cretaceous period one of the main mountain-building episodes in New Zealand's history took place. Although basinal sedimentation continued through the Cretaceous period in eastern New Zealand, elsewhere this basin was compressed, and the sediments were intensely crumpled, broken and raised above the sea, probably forming a large, mountainous landmass. Some of the geoclinal sediments, now exposed over much of Otago, alpine Westland, and parts of the Marlborough Sounds, were metamorphosed into schist and gneiss by high temperatures and the tremendous deforming pressures to which the geocline was subjected. This intense folding of the strata occurred approximately 100 million years ago in the mid-Cretaceous period. Slowly the mountains were eroded and gradually a land of low relief was produced. The sea gradually advanced over the eroded stumps of the Mesozoic mountains, beginning its transgression earlier in some areas than in others. In the early Cretaceous period the land became submerged in the region of present Northland and the eastern margins of the North and South Islands, and thick deposits of mudstone and sandstone accumulated in some of these areas. At the close of the Mesozoic era, and in the very early Tertiary era, the land became so reduced in size that little sediment was produced and only comparatively thin deposits of bentonitic and sulphurous muds, and fine, white foraminiferal limestone accumulated. During this time, New Zealand's main coal deposits accumulated in swamps on the surface of the old land. These became buried by marine deposits as the sea continued its transgression in the Eocene period. By the Oligocene period most of the land was submerged and in shallow waters free of land sediments, thick deposits of shell and foraminiferal limestone accumulated. Scattered remnants of this Oligocene limestone are used for most of New Zealand's cement and agricultural lime.

After the Oligocene submergence, earth movements became more vigorous; many ridges rose from the sea as islands, and sank or were worn down again; sea basins formed and were rapidly filled with sediments. New Zealand's late Tertiary environment has been described by Sir Charles Fleming (Tuatara, June 1962) as follows: “The pattern of folds, belts and troughs that developed was on a finer scale than in the Mesozoic… the land moved up and down as a series of narrow, short, interfingering or branching folds …. We can think of Tertiary New Zealand as an archipelago … a kind of writhing of part of the mobile Pacific margin seems to have gone on.” The thick deposits of soft grey sandstone and mudstone that now make up large areas of the North Island and some parts of the South Island, are the deposits that accumulated in the many sea basins that developed in the later Tertiary.

Late in the Cenozoic era, in the Pliocene and Pleistocene periods between 6 million and 1 million years ago, another great episode of mountain building took place. Earth movements became intense, and slowly pushed up the Southern Alps and New Zealand's other main mountain chains. It was during this period that the general size and shape of the present islands of New Zealand was determined. Much of the movement during this mountain-building period (the Kaikoura Orogeny) took the form of displacement of blocks of the earth's crust along fractures called faults. The total movement of blocks adjacent to major faults amounted to thousands of metres. It must have been achieved very slowly, probably by innumerable small movements, each less than a few metres. The blocks adjacent to ‘transcurrent’ faults moved both vertically and laterally along the faults. The New Zealand landscape today in some regions shows well-preserved, tilted fault blocks bounded by fault scarps (steep faces hundreds or even thousands of metres high). From Milford Sound to Cook Strait, an almost unbroken depression, formed by river valleys and low saddles on the intervening ridges, marks the line of New Zealand's Alpine Fault. Contrasting rock types occur on either side of the fault. This is illustrated by the 480 kilometre separation of Permian igneous rocks, which occur in Nelson and western Otago. Fault movements continue to the present day and have accompanied several major earthquakes of the past century. Many minor but revealing landscape features, such as scarplets or offset ridges, or streams, show where the movement has been occurring over recent centuries.

Erosion has transformed the landscape during this time, carving detailed patterns of peaks, ridges, valleys and gorges. The deposition of debris has built up alluvial plains, shingle fans and other construction forms. At the coast, waves have eaten back the headlands and built beaches, spits and bars. The late Pleistocene glaciers carved the fiords of Fiordland and the valleys occupied by most of the South Island lakes; there were also small glaciers on Ruapehu, where remnants survive, on Mount Taranaki and the Tararua Range. Sea-level changes accompanied the formation and later melting of global glacial ice, affecting the erosion and deposition of the rivers. These changes were responsible for the formation of many prominent river terraces.

Volcanic activity over the past few million years has played an important part in shaping the landscape. Banks Peninsula, a twin volcanic dome in Canterbury, also achieved much of its growth then. The largest volcanic outpourings of late geological times in New Zealand has been in the region between Tongariro National Park and the Bay of Plenty coast; andesite lava, scoria, and ash were erupted in the Pleistocene period and later, to build the volcanoes, Ruapehu, Tongariro, and Ngauruhoe. More than 8000 cubic kilometres of molten rhyolitic magma was erupted in the form of ignimbrite pumice and rhyolite lava, building up the Volcanic Plateau, which is one of the largest and youngest accumulations of acid volcanic rocks in the world. Mount Taranaki is an andesitic stratovolcano, with the remnants of three other volcanic cones nearby; all are of Pleistocene age. In the Waikato there are eroded Pleistocene cones of andesitic composition associated with a number of alkaline eruptive centres. The largest is Pirongia, a basaltic andesite cone some 900 metres high. Auckland city and the area just south has been the scene of many eruptions of basalt lava and scoria in Pleistocene and Holocene times, and many small scoria cones can be seen there. Late Tertiary and Quaternary basaltic eruptions in North Auckland have built lava plateaus and many young cones. From these volcanic outpourings some valuable mineral resources have been derived. The ironsands mined on the west coast of the North Island are concentrations of magnetite and ilmenite, which have been eroded from volcanic rocks.

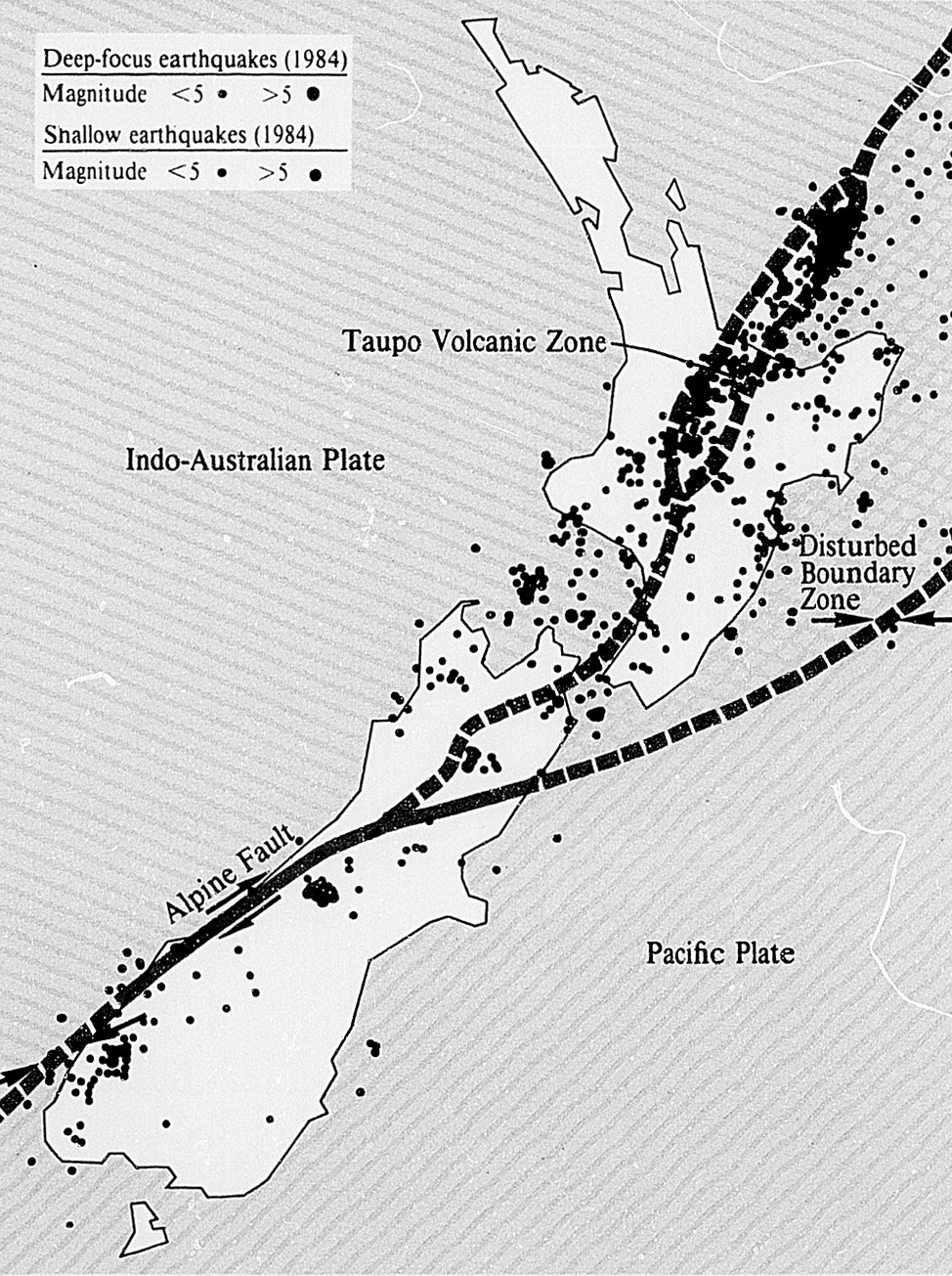

Compared with some other parts of the almost continuous belt of earthquake activity around the rim of the Pacific—such as Japan, Chile, and the Philippines—the level of seismic activity in New Zealand is moderate, although earthquakes are common. It may be roughly compared with that prevailing in California. A shock of Richter magnitude 6 or above occurs on the average about once a year, a shock of magnitude 7 or above once in 10 years, and a shock of about magnitude 8 perhaps once a century, but in historic times only one shock (the south-west Wairarapa earthquake in 1855) is known to have reached this magnitude.

Other natural disasters and accidents are together responsible for more casualties than earthquakes. The most serious seismic disasters in New Zealand have been the Hawke's Bay earthquake of 1931 in which 256 deaths occurred, and the Buller earthquake of 1929 in which there were 17 deaths. The total resulting from all other shocks since 1840 is less than 15 deaths. The last earthquake to cause deaths occurred at Inangahua in 1968, when three people died, while the most recent damaging earthquake was at Edgecumbe in the Bay of Plenty in March 1987.

The process of earthquake occurrence is understood in terms of a large volume of the earth's crust being subjected to strain by the relentless movement of the great plates of the earth's surface against each other. The strain eventually exceeds the strength of the rock, which ruptures. Energy is radiated outwards in the form of elastic waves, which can be felt at places near the origin, and detected by sensitive instruments at greater distances. In large shallow earthquakes the rupture may appear at the surface, forming or renewing movement on a geological fault. In regions where the majority of earthquakes are very shallow, such as California, there is a tendency for the earthquake origins to cluster near geological fault traces, but in regions of deeper activity, such as New Zealand, this is not so. There is little activity near the Alpine Fault, which stretches for some 500 kilometres from Milford Sound to Lake Rotoiti, and is considered one of the world's largest and most active faults.

Within New Zealand at least two separate systems of seismic activity can be distinguished. The Main Seismic Region covers the whole of the North Island except the Northland peninsula, and the part of the South Island north of a line passing roughly between Banks Peninsula and Cape Foulwind. The Southern, or Fiordland, Seismic Region includes southern Westland, western Southland, and western Otago. Less clearly defined activity covers the remainder of the two main islands, and extends eastwards from Banks Peninsula to include the Chatham Islands.

Shallow earthquakes, which are the most numerous, originate within the Earth's crust which in New Zealand has an average thickness of some 35 kilometres. These shocks are responsible for almost all damage to property, and are widely scattered throughout the country. In historically recent times, the Main and Fiordland Seismic Regions have been significantly more active than the rest of New Zealand, but neither the Central Seismic Region, which lies between them, nor the northern peninsula has been free from damaging shocks. The details of the present pattern are not necessarily unchanging, and could alter significantly after the occurrence of a major earthquake. Because of this, because of the broader geophysical setting, and because of the distance to which the effects of a large earthquake extend, it would be highly imprudent to treat any part of New Zealand as completely free from the risk of serious earthquake damage.

LOCATION OF EARTHQUAKES AND VOLCANIC ACTIVITY

Many active regions of the Earth have only shallow earthquakes, but in others shocks have been known to occur at depths as great as 700 kilometres below the surface. It is thought that these deep shocks originate within the edges of crustal plates that have been drawn down or thrust beneath their neighbours. Such deep events are common in both the Main and Fiordland Seismic Regions of New Zealand, but their relative positions with respect to the shallow activity and to other geophysical features are rough mirror images. This is believed to indicate that in the North Island the edge of the Pacific Plate lies below that of the Indian Plate, while in the south of the South Island the Pacific Plate is uppermost and the Indian Plate has been thrust beneath it.

The most important system of deep shocks in New Zealand lies in a well-defined zone beneath the Main Seismic Region, stretching from the Bay of Plenty to Nelson and Marlborough. The maximum depth of occurrence is about 400 kilometres at the northern end, and decreases evenly to a depth of about 200 kilometres before the southern boundary of the region is reached. Along the whole of the system, there is also a regular decrease in depth from west to east. In northern Taranaki, near the western limit of this activity, a small isolated group of shocks at a depth of about 600 kilometres has also been recorded. In the Central Seismic Region only shallow shocks are known. The maximum depth of earthquakes appears to be less than 150 kilometres in the Fiordland Region where the deep activity is more concentrated than in the north, lying close to Lakes Te Anau and Manapouri.

Both earthquakes and volcanoes are found in geophysically disturbed regions, but large earthquakes are rare, although small earthquakes usually accompany volcanic eruptions. Regions of active volcanism are also subject to periodic outbreaks of small earthquakes, all of similar magnitude, and very numerous, known as ‘earthquake swarms’. Although the number of shocks may cause alarm, it is unusual for even minor damage to result. There is not often a simultaneous volcanic outbreak, but swarms are rare in non-volcanic regions. In New Zealand they have occurred in the volcanic zone that includes Mount Ruapehu and White Island, the Coromandel Peninsula, parts of Northland, and Taranaki.

Earthquakes in 1987. The largest was the Edgecumbe earthquake on 2 March, with a magnitude of 6.3. The next most damaging was that four days later, in Pegasus Bay, which caused some damage in Christchurch and North Canterbury.

Many other earthquakes occurred at greater depths in the earth, and so were not dangerous. The largest of these was on 23 March, just north of Te Puke in the Bay of Plenty. It was of magnitude 6.0, but was 350 km deep and so was felt only slightly, but as far south as Wellington.

Each year analysis of earthquake data from a network of record stations is completed by the Seismological Observatory of the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research. This analysis allows scientists to pinpoint the location, intensity and depth of earthquakes—information that can be used to pick trends and in the theory of plate tectonics.

New Zealand lies in the mid-latitude zone of westerly winds, in the path of an irregular succession of anticyclones, which move eastwards every six to seven days. The centres of these anticyclones generally track across the North Island, more northerly paths being followed in spring, and southerly paths in autumn and winter. Anticyclones are areas of descending air, and settled weather, with little or no rain, which may bring clear skies, or low cloud and fog. Between the anticyclones are troughs of low pressure, which extend northwards from low pressure depressions moving eastwards far to the south of New Zealand. Within these troughs there are often cold fronts, oriented north-west to south-east, which produce one of the commonest types of weather sequence over the country: as the front approaches from the west, north-westerly winds become stronger and cloud increases, followed by a period of rain for several hours as the front passes over, and then a change to cold showery south-westerly winds.

The mountain chain extending the length of the country has a major effect on the climate of its various regions, and produces much sharper climatic contrasts from west to east, than from north to south. In some inland areas of the South Island, just east of the mountains, the climate is distinctly ‘continental’ in character, with large daily and seasonal temperature variations, despite the fact that no part of the country is more than 130 kilometres from the sea. Ophir in Central Otago has the greatest extreme temperature range of 55°c.

The prevailing wind direction is westerly, although in individual months easterlies may predominate, and north of Taranaki the general flow is south-westerly. In the North Island winds generally decrease for a period in the summer or early autumn, but in many parts of the South Island July and August are the least windy months. The blocking effect of the mountain ranges modifies the westerly wind pattern. Wind strength decreases on the western side, but increases through Cook Strait, Foveaux Strait, and about the Manawatu Gorge. Air is also forced upwards over the ranges, which results in a warm drying (föhn) wind in the lee areas to the east of both islands. Wellington averages 173 days a year with wind gusts greater than about 60km/h, compared with 30 for Rotorua, 31 for Timaru, and 35 for Nelson. Sea breezes are the predominant winds in summer in many coastal places, such as Canterbury, where the north-easterlies are almost as frequent as the predominant south-westerlies.

The distribution of rainfall is mainly controlled by mountain features, and the highest rainfalls occur where the mountains are exposed to the direct sweep of the westerly and north-westerly winds. The mean annual rainfall ranges from as little as 300 mm in a small area of Central Otago to over 8000 mm in the Southern Alps. The average for the whole country is high, but for the greater part lies between 600 mm and 1500 mm. The only areas with average rainfalls under 600 mm are found in the South Island to the east of the main ranges, and include most of Central and North Otago, and South Canterbury. In the North Island, the driest areas are central and southern Hawke's Bay, Wairarapa, and Manawatu, where the average rainfall is 700–1000 mm a year. Of the remainder, much valuable farm land, chiefly in northern Taranaki and Northland, has upwards of 1500 mm. Over a considerable area of both islands rainfall exceeds 2500 mm a year.

For a large part of the country the rainfall is spread evenly through the year. The greatest contrast is found in the north, where winter has almost twice as much rain as summer. However, the predominance of winter rainfall diminishes southwards: it is still discernible over the northern part of the South Island, but over the southern half, winter is the season with least rainfall, and a definite summer maximum is found inland due to the effect of convectional showers.

Rainfall is also influenced by seasonal variations in the strength of the westerly winds. Spring rainfall is increased west of, and in, the ranges as the westerlies rise to their maximum about October, with a complementary decrease of rainfall in the lee of the ranges. Areas which are exposed to the west and south-west experience much showery weather, and rain falls on roughly half the days of the year. Over most of the North Island there are at least 130 rain days a year (days with at least 1.0 mm of rain)—except to the east of the ranges where in places there are fewer than 110 rain days. Those areas of the South Island with annual rainfall under 600 mm generally have about 80 rain days a year. In the far south the frequency of rain increases sharply, rain days exceeding 200 a year in Stewart Island and Fiordland.

On the whole the seasonal rainfall does not vary greatly from year to year, its reliability in spring being particularly advantageous for agriculture. It is least reliable in late summer and autumn, when very dry conditions may develop east of the ranges, particularly in Hawke's Bay. The highest daily rainfall on record is 582 mm, which occurred at Rapid Creek (Hokitika), where the mean annual rainfall exceeds 6000 mm. Areas with a marked lower annual rainfall can be subject to very heavy daily falls: such areas are found in northern Hawke's Bay and north-eastern districts in the Auckland province. By contrast, in the Manawatu district, Otago, and Southland, daily falls reaching 80 mm are very rare.

Mean temperatures at sea level decrease steadily southwards from 15°C in the far north to 9°C in the south of the South Island. Temperatures also drop with altitude: by about 2°C per 300 metres. January and February, with approximately the same mean temperature, are the warmest months of the year, and July is the coldest. Highest temperatures are recorded east of the main ranges, where they exceed 30°C on a few afternoons in most summers. The extremes for New Zealand are 42°C which has been recorded in three places, at Awatere Valley (Marlborough), Christchurch, and Rangiora (Canterbury); and — 19°C at Ophir (Central Otago). The annual range of mean temperature (the difference between the mean temperature of the warmest and coldest months) is small. In Northland and in western districts of both islands it is about 8°C and for the remainder of the North Island and east coast districts of the South Island it is 9 to 10°C. Further inland the annual range exceeds 11°C in places, reaching a maximum of 14°C in Central Otago, where there is an approach to a ‘continental’ type of climate.

The sunniest places are near Blenheim, the Nelson-Motueka area, and Whakatane, where the average duration of bright sunshine exceeds 2350 hours a year. The rest of the Bay of Plenty and Napier are only slightly less sunny. A large portion of the country has at least 2000 hours, and even Westland, despite its high rainfall, has 1800 hours. Southland and coastal Otago, where sunshine drops sharply to about 1700 hours a year, lie on the northern fringe of a broad zone of increasing cloudiness. A pleasant feature of the New Zealand climate is the high proportion of sunshine during the winter months. Although there is a marked increase in cloudiness in the North Island in winter, there is little seasonal change in the South Island, except in Southland.

The number of severe hailstorms reported annually over the whole country averages nine, but this figure varies yearly from four to 20. Severe hailstorms occur widely throughout the country, but the areas most affected are Canterbury, the low country of central Hawke's Bay, and a small area south and west of Nelson. Most of the hailstones are small, but occasionally larger stones cause local damage to glasshouses and orchards. Thunderstorms are not numerous. Their frequency is greatest in the north and western side of the country, where thunder is heard on 15 to 20 days a year. On the east coast of the South Island the average is commonly less than five. Tornadoes show a similar pattern to thunderstorms, except that maximum frequency occurs in the Waikato and Bay of Plenty. An average of about 20 tornadoes and waterspouts is reported each year, but most of these are small.

Local variations in frostiness are considerable, even within quite small areas. For example, at Albert Park, Auckland, the screen minimum thermometer has registered below 0°C only once in 65 years, while further up the harbour at Whenuapai aerodrome there are on average eight screen frosts each year. Favourable sites in coastal areas of Northland are free of frost, although further inland light frosts occur frequently in the winter months. Excluding the uninhabited alpine areas, the coldest winter conditions are experienced in Central Otago, the Mackenzie Plains of inland Canterbury, and on the central plateau of the North Island, but even in these areas night temperatures of — 12°C are rarely recorded. Elsewhere in the North Island the winters are mild, and in both islands sheep and cattle remain in the open all year round.

The North Island has a small permanent snow field above 2500 metres on the central plateau, but the snow line rarely descends below 600 metres even for brief periods in winter. In the South Island snow falls on a few days each year in eastern coastal districts, where in some years it may lie for a day or two even at sea level, but in Westland it does not lie at sea level. The snow line on the Southern Alps is about 2000 metres in summer, being slightly lower on the western side where the Franz Josef and Fox Glaciers descend through heavy bush to within 300 metres of sea level. In inland Canterbury and Otago, where there are considerable areas of grazing lands above 300 metres, snowfalls are heavier and more persistent, and have caused serious sheep losses during severe winters. In that area, however, it is rare for the winter snow line to remain below 1000 metres for extended periods.

Humidity is commonly between 70 and 80 percent in coastal areas and about 10 percent lower inland. The daily variation is greater than the difference between summer and winter. Very low humidity (from 30 percent down to 5 percent) occurs at times in the lee of the Southern Alps, where the föhn wind (the Canterbury nor-wester) is often very marked. Cool south-westerlies are also at times very dry when they reach eastern districts. In Northland the humid mid-summer conditions are inclined to be oppressive, although temperatures rarely reach 30°C. Dull, humid spells are generally not prolonged anywhere, but their frequency shows a marked increase in the south.

Table 1.6. SUMMARY OF CLIMATE OBSERVATIONS TO 1980, RAINFALL, FROST AND SUNSHINE

| Station | Height | Rainfall | Screen frost† | Ground frost‡ | Bright sunshine | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual | Rain days* | |||||

* A rain day is one when 1.0 mm or more of rain was recorded. † A screen (or air) frost occurs when the temperature in the screen (at 1.3 metres above ground) falls below 0°C. ‡ A ground frost occurs when the grass minimum thermometer (25 mm above short grass) reads − 1.0°C or lower. Source: New Zealand Meteorological Service. | ||||||

| metres | mm | no. days | no. days | hours | ||

| Kaitaia Airport | 80 | 1,418 | 138 | 0 | 1.7 | 2,113 |

| Kerikeri | 73 | 1,682 | 135 | 1.0 | 24.9 | 2,004 |

| Dargaville | 20 | 1,248 | 149 | 5.0 | 16.8 | 1,956 |

| Auckland (Albert Park) | 49 | 1,185 | 140 | 0 | 4.2 | 2,102 |

| Tauranga Airport | 4 | 1,349 | 118 | 5.3 | 56.9 | 2,277 |

| Hamilton (Ruakura) | 40 | 1,201 | 131 | 25.5 | 71.8 | 2,006 |

| Rotorua Airport | 287 | 1,491 | 123 | 21.2 | 56.9 | .. |

| Gisborne Airport | 4 | 1,058 | 113 | 6.8 | 40.7 | 2,204 |

| Taupo | 376 | 1,178 | 122 | 37.1 | 71.4 | 2,021 |

| Taumarunui | 171 | 1,443 | 140 | 34.7 | 64.7 | 1,704 |

| New Plymouth Airport | 27 | 1,529 | 144 | 2.0 | 12.8 | 2,165 |

| Waiouru | 823 | 1,048 | 137 | 65.1 | 100.6 | .. |

| Napier | 2 | 824 | 95 | 8.8 | 38.6 | 2,245 |

| Wanganui | 22 | 906 | 115 | 3.5 | 10.7 | 2,087 |

| Palmerston North (DSIR) | 34 | 995 | 126 | 13.5 | 54.4 | 1,794 |

| Masterton (Waingawa) | 114 | 971 | 124 | 31.4 | 89.1 | 2,004 |

| Wellington (Kelburn) | 126 | 1,240 | 125 | 0 | 15.0 | 2,019 |

| Nelson Airport | 2 | 986 | 99 | 37.7 | 89.7 | 2,397 |

| Blenheim | 4 | 642 | 81 | 38.5 | 86.1 | 2,447 |

| Westport Airport | 2 | 2,192 | 168 | 1.0 | 39.3 | 1,925 |

| Hanmer Forest | 387 | 1,163 | 114 | 81.7 | 139.5 | 1,898 |

| Christchurch | 7 | 666 | 87 | 35.7 | 88.7 | 1,974 |

| Hokitika Airport | 39 | 2,783 | 168 | 16.0 | 56.4 | 1,846 |

| Lake Tekapo | 683 | 597 | 72 | 100.1 | 175.8 | 2,217 |

| Timaru | 17 | 587 | 81 | 37.9 | 87.8 | 1,869 |

| Queenstown | 329 | 805 | 92 | 50.3 | 140.7 | 1,921 |

| Alexandra | 141 | 343 | 65 | 86.2 | 154.0 | 2,064 |

| Dunedin (Musselburgh) | 2 | 784 | 120 | 9.7 | 77.7 | 1,676 |

| Gore | 72 | 836 | 136 | 43.7 | 100.2 | 1,698 |

| Invercargill Airport | 0 | 1,037 | 157 | 46.3 | 111.1 | 1,621 |

| Milford Sound | 3 | 6,267 | 182 | 28.5 | 56.1 | .. |

Table 1.7. SUMMARY OF CLIMATE OBSERVATIONS TO 1980, AIR TEMPERATURE

| Mean daily* | Daily maximum | Daily minimum | Annual extremes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | July | January | July | January | July | Max. | Min. | |

* The mean daily temperature is the average of the maximum and minimum temperature for a given day. Source: New Zealand Meteorological Service. | ||||||||

| degrees Celsius | ||||||||

| Kaitaia Airport | 19.3 | 11.7 | 23.8 | 15.2 | 14.8 | 8.1 | 30.5 | -0.5 |

| Kerikeri | 18.9 | 10.8 | 24.5 | 15.5 | 13.3 | 6.1 | 34.3 | -2.0 |

| Dargaville | 18.6 | 10.7 | 23.4 | 14.9 | 13.7 | 6.5 | 32.1 | -5.0 |

| Auckland (Albert Park) | 19.4 | 10.9 | 23.1 | 14.1 | 15.7 | 7.8 | 32.4 | -0.1 |

| Tauranga Airport | 18.5 | 9.3 | 23.6 | 14.1 | 13.3 | 4.5 | 33.3 | -5.3 |

| Hamilton (Ruakura) | 17.8 | 8.3 | 23.9 | 13.5 | 11.6 | 3.1 | 34.7 | -9.9 |

| Rotorua Airport | 17.6 | 7.5 | 22.8 | 11.9 | 12.4 | 3.0 | 29.8 | -5.7 |

| Gisborne Airport | 18.7 | 9.1 | 24.4 | 13.8 | 13.0 | 4.4 | 38.1 | -3.4 |

| Taupo | 17.3 | 6.5 | 23.5 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 1.9 | 33.0 | -6.3 |

| Taumarunui | 18.3 | 7.3 | 24.8 | 12.5 | 11.8 | 2.1 | 33.9 | -6.4 |

| New Plymouth Airport | 17.1 | 9.1 | 21.4 | 13.0 | 12.7 | 5.3 | 30.3 | -2.4 |

| Waiouru | 13.8 | 4.0 | 19.2 | 7.6 | 8.2 | 0.3 | 28.5 | -9.0 |

| Napier | 18.9 | 9.0 | 23.8 | 13.4 | 14.1 | 4.6 | 35.8 | -3.9 |

| Wanganui | 17.8 | 8.7 | 21.9 | 12.5 | 13.7 | 4.9 | 31.2 | -2.3 |

| Palmerston North (DSIR) | 17.3 | 8.0 | 21.9 | 11.9 | 12.8 | 4.0 | 31.7 | -6.0 |

| Masterton (Waingawa) | 17.3 | 7.1 | 23.7 | 11.8 | 10.8 | 2.4 | 35.2 | -6.9 |

| Wellington (Kelburn) | 16.4 | 8.2 | 20.0 | 10.9 | 12.8 | 5.5 | 31.1 | -1.9 |

| Nelson Airport | 17.2 | 6.5 | 21.9 | 11.9 | 12.5 | 1.1 | 36.3 | -6.6 |

| Blenheim | 17.8 | 7.0 | 23.6 | 12.4 | 12.0 | 1.5 | 36.0 | -8.8 |

| Westport Airport | 15.8 | 8.2 | 19.5 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 4.3 | 28.6 | -3.5 |

| Hanmer Forest | 15.6 | 3.9 | 22.2 | 9.2 | 9.0 | -1.3 | 37.1 | -13.2 |

| Christchurch | 16.6 | 5.9 | 21.5 | 10.3 | 11.6 | 1.4 | 41.6 | -7.1 |

| Hokitika Airport | 15.3 | 7.2 | 19.2 | 11.7 | 11.4 | 2.7 | 27.5 | -3.2 |

| Lake Tekapo | 14.8 | 1.6 | 21.3 | 6.0 | 8.3 | -2.8 | 33.3 | -15.6 |

| Timaru | 16.2 | 5.3 | 21.4 | 9.8 | 11.0 | 0.7 | 37.2 | -6.8 |

| Queenstown | 15.8 | 3.7 | 21.7 | 7.7 | 9.9 | -0.4 | 34.1 | -7.8 |

| Alexandra | 17.0 | 2.6 | 23.2 | 7.3 | 10.7 | -2.2 | 37.2 | -11.7 |

| Dunedin (Musselburgh) | 15.0 | 6.4 | 19.0 | 9.9 | 11.1 | 2.9 | 34.5 | -8.0 |

| Gore | 15.0 | 4.6 | 20.9 | 9.1 | 9.2 | 0.2 | 35.0 | -8.9 |

| Invercargill Airport | 13.7 | 5.1 | 18.4 | 9.4 | 8.9 | 0.8 | 32.2 | -7.4 |

| Milford Sound | 14.4 | 5.4 | 18.5 | 9.3 | 10.3 | 1.5 | 28.3 | -4.9 |

The vegetation and wildlife of New Zealand are the product of not only natural factors during tens of millions of years, but also human factors over the last 1000 years. The New Zealand landmass is a fragment of the ancient southern continent of Gondwanaland, which has been isolated for over 100 million years, allowing many ancient plants and animals to survive. Although New Zealand has undergone many physical and climatic changes, such as mountain building, volcanic activity, and glaciation, parts of the landmass have remained in continuous existence with part of their original complement of plants and animals.

New Zealand is now a very diverse land and changes from being almost subtropical (‘winterless’) in the north, to cool temperate, even subantarctic in the south, with a very wet, mild climate in the west, and a much drier, sometimes almost continental climate, in the east. A long and exceptionally diverse coastline, with many islands, produces habitats for coastal and lowland plants and animals, and there are extensive montane and alpine habitats as well. Geological variation has meant species have adapted to habitats based on soils derived from limestone, volcanic rock, serpentine, alluvial muds and gravels, and peat. Such diversity has led to New Zealand being classified into over 260 ecological districts, each with a distinct blend of topography, climate, vegetation, and wildlife.

Superimposed on natural diversity has been 1000 years of human activity; harvesting of naturally occurring species, introduction of species from elsewhere, and transformation of natural vegetation into farmland by fire, logging, and drainage. While approximately 80 percent of the land area was forested before humans arrived, only 23 percent remains forested, mainly in the mountainous hinterland.

The vegetation and wildlife of New Zealand today is made up of different bio-geographic elements. The Gondwanaland element, consists of ancient plants and animals: conifers such as kauri (Agathis australis), frogs (Leiopelma), reptiles like tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus), large ground snails (Powelliphanta), and flightless birds such as the kiwi (Apteryx spp.) and the now extinct moa (Dinothiformes). A tropical element includes the nikau palm, kie kie (Freycenetia), tree ferns, many northern forest trees, tropical snails (Placostylis), and earthworms. An Australian element includes many ferns, orchids, small seeded tree species like manuka (Leptospermum scoparium), insects, and birds (such as the nectar-feeding tui (Prosthemadera novaeseelandiae), parakeets, and many wetland birds). A Pacific element includes trees like pohutukawa (Metrosideros excelsa), numerous ferns, and migratory birds like the shining cuckoo (Chalcites lucidus). A subantarctic or circumpolar element includes beech (Nothofagus), which occurs also in South America and Southern Australia and was once present on Antarctica, and the world's largest assemblage of several characteristically southern bird groups such as penguins, albatrosses, and petrels. A South American element includes Fuchsia. A cosmopolitan mountain element entered New Zealand along the mountain and island chain from South-east Asia and includes plants such as buttercups, daisies, veronicas and gentians. A cultural element of recent human origin comes from all parts of the world (particularly Europe, North America, Australia and South Africa), and consists of trees, horticultural plants, weeds, mammals, birds, and many other groups.

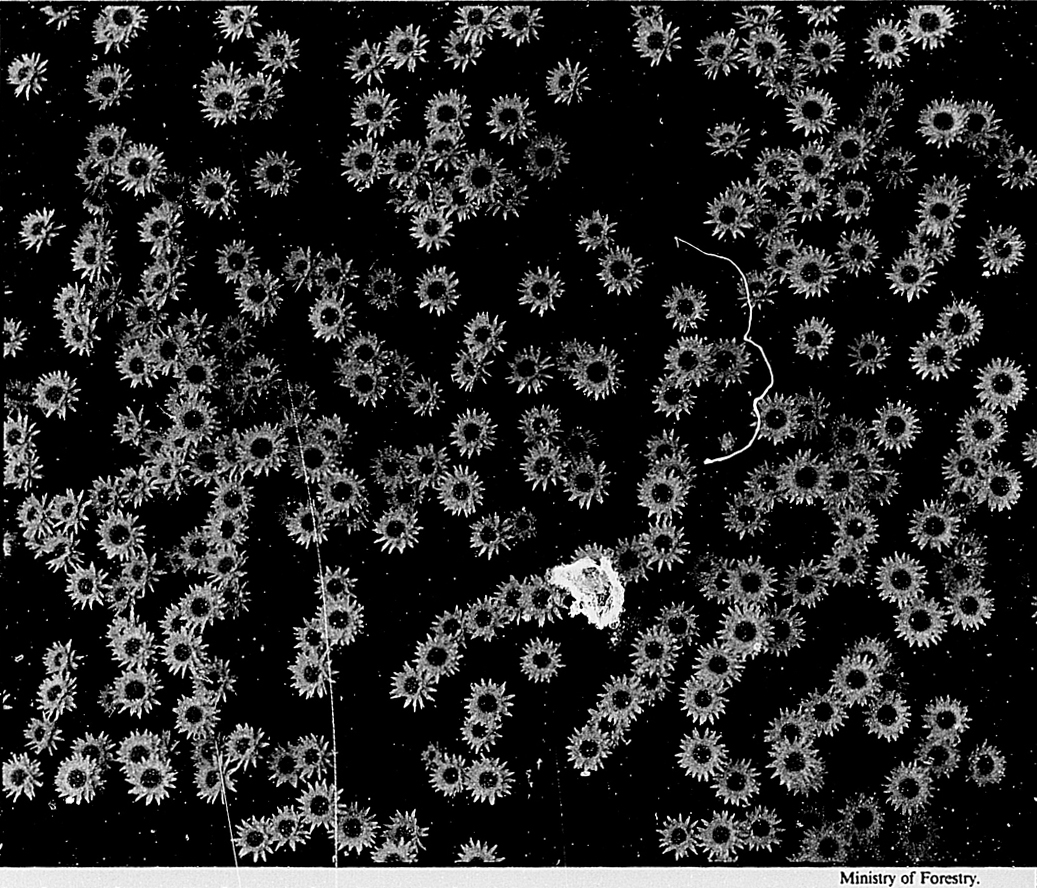

Everlasting daisies, North-west Nelson Forest Park.

Northern (subtropical), central (temperate), and southern (subantarctic) marine areas can also be recognised, each with characteristic species; for instance rock oyster, blue mussel and dredge oyster, respectively. Bull kelp is a notable southern species. Some very unusual marine animals occur, including black coral and ancient brachiopods in the southern fiords, and recently discovered sea daisies—starfish relatives which live on sunken wood at a depth of 1000 metres. The complex sea floor means that shore, continental shelf, and deep water species occur close together, resulting in diverse marine life.

Uniqueness is a feature of the natural life of New Zealand. Foremost is the absence, apart from two species of bat, of local land mammals, which had not evolved at the time New Zealand became separate. Many flightless birds and insects have evolved. The most remarkable birds were some 12 species of moa, forest and shrub browsers that took the place of large herbivores in other parts of the world. Moa became extinct during Maori times, but other flightless birds remain, including kiwi, kakapo (a nocturnal parrot—the largest in the world), and weka (a scavenging rail). Flightless insects are numerous, including many large beetles and cricket-like weta.

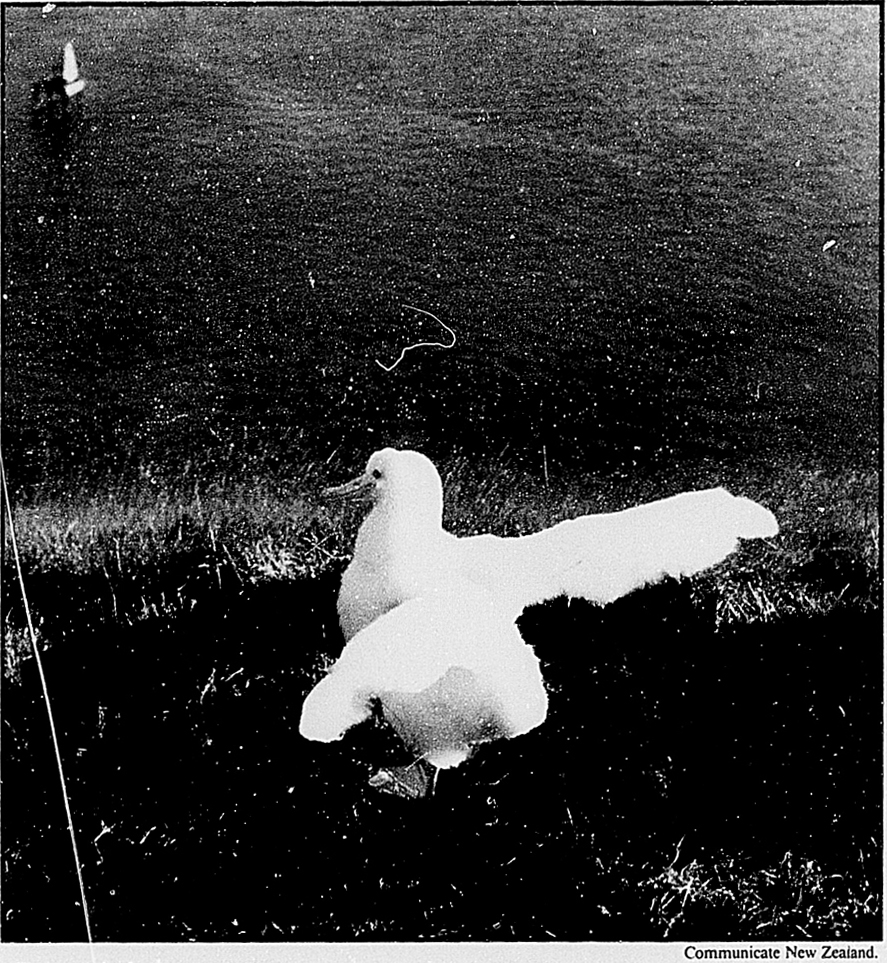

Albatross chick, Otago.

The absence of mammals also meant that birds became important as seed-dispersing agents, so that most forest plants bear small berries, including the giant conifers (podocarps), the smaller canopy trees, and even some forest-floor herbs. Some alpine plants produce berries, dispersed by the New Zealand pipit and the kea (mountain parrot). As a consequence of the great physical and climatic upheavals which New Zealand has undergone the forest has been influenced by extinction. Coconut palms once occurred in New Zealand, and fossil remains of kauri, now limited to the northern North Island, have been found south to Canterbury. Some tropical plant groups are represented by a single species, surviving only on protected islands, or in the far north. Some, like Tecomanthe are known from only a single plant in the wild.

The range of bird species is also very limited in comparison with other temperate land masses of similar size. The endemic family of wattle birds contains only four species. One of these, the huia, is now extinct and considerable natural extinction has occurred in the past. On the other hand, there has been great diversification among smaller life-forms, such as tiny forest-floor snails, spiders, aquatic caddis flies, lichens, mosses and liverworts. Of note is the diversity of alpine plants such as daisies (Celmisia, Senecio), veronica (Hebe), native carrot (Aciphylla) and buttercups. Many of these plants produce rosettes of large leaves, which seem to adapt the plants to cold, windy, subantarctic conditions in the relatively recently-formed high mountains. A second group of plants adapted to cold, windy conditions are cushion plants, some of which form remarkable mounds called ‘vegetable sheep’.

In the forest and along its margins divaricating shrubs occur with tangled and crisscrossed branches bearing tiny leaves. Sometimes these shrubs are the juvenile forms of tree species, but more often are the adult itself. Nowhere else in the world is this peculiar growth form so abundant. It may be an adaptation to browsing by the now extinct moa, or it may help plants to adapt to cold or dry conditions.

Although many New Zealand plants and animals occupy very specialised habitats, droughts, high winds, floods, and erosion mean that many species need to be highly adaptable. Accordingly, many insects, such as native bees, gather food from a wide variety of sources, and some forest species, like beech, regenerate best after the parent forest has been destroyed (by volcanic eruption for example).

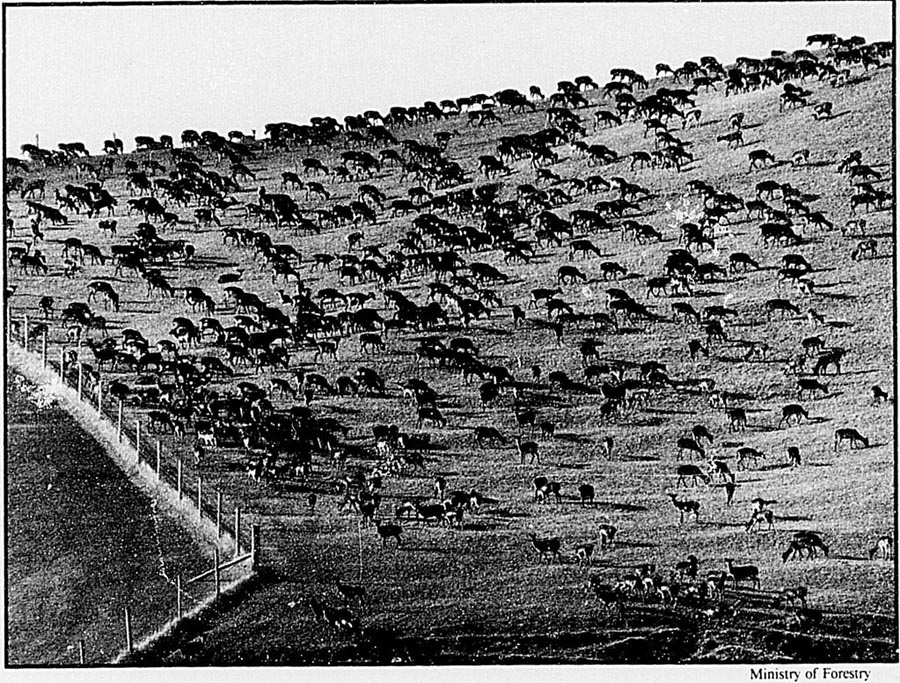

However, the overwhelming character of the land-based wildlife is its dependence on forest, and its vulnerability to introduced predators such as rats. The forests and natural grasslands have also been severely modified by introduced browsers such as possums, deer and goats, and some introduced plants, like marram grass, have taken over the places where native species would normally grow.

A vast proportion of the native animals and plant species are found only in New Zealand. Virtually all insects, spiders and snails, and all earthworms are restricted to New Zealand, as are most birds and plants, most freshwater fish (27 species), and all reptiles (38 species).

Table 1.8 summarises the numbers of native and introduced species in New Zealand today, although many figures are approximate and may change after future scientific investigation.

Table 1.8. SELECTED GROUPS OF NATIVE AND INTRODUCED SPECIES

| Group | Number of species | Percentage endemic* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Introduced | Native | ||

* Native species not found anywhere else. † Estimated. Source: Department of Conservation. | |||

| Marine algae (seaweeds) | 3 | 900† | 43 |

| Bryophytes— | |||

| Mosses | 15 | 485 | 28 |

| Liverworts | .. | 500 | .. |

| Ferns and allies | 20 | 163 | 41 |

| Conifers | 30 | 20 | 100 |

| Flowering plants | 1 700 | 1 813 | 84 |

| Earthworms | 40 | 178 | 100 |

| Landsnails/slugs | 12 | 520† | 99 |

| Spiders/harvestmen | 60 | 2 500† | 90 |

| Insects | 1 100 | 9 460 | 90 |

| Freshwater fish | 23† | 27 | 85 |

| Amphibia | 2 | 3 | 100 |

| Reptiles | 1 | 38 | 100 |

| Birds— | |||

| Land/freshwater | 33 | 65 | 57 |

| Mammals— | |||

| Marine | 1 | 34 | 6 |

| Land | 33 | 2 | 100 |

Forests. Apart from mountains above bush-line, swamps, coastal dunes, and some dry inland basins, most of New Zealand was originally forest-covered. The forests were reduced by a third by Maori clearance before European settlement, and a further third by European clearance over the last 150 years, so that now only 23 percent of New Zealand remains in native forest. Much occurs in mountainous areas, and most is now protected.

There is a wide range of natural forest types. Around the coast is a fragmented narrow band of plants with varying degrees of salt tolerance, (including mangroves, nikau palm and mostly tropical Pacific species, such as karaka and pohutukawa. Coastal forests are particularly important habitats for marine birds (for example various petrels and penguins), and offshore islands form refuges for tuatara, flightless, insects and snails. The characteristic New Zealand forest type is warm temperate evergreen rain forest. In the far north this is dominated by kauri and various broad-leved species, though little original forest remains. Swamp forest dominated by the podocarp kahikatea (Dacrycarpus dacrydioides) was once extensive, and remains prominent in the western South Island. Elsewhere the podocarps (rimu, totara, matai, and miro) are associated with a diverse range of broad-leaved evergreen tree species, ferns, vines and epiphytes, forming dense and complex multi-storeyed communities at low altitudes. The range of species gradually diminishes with both increasing altitude and increasing latitude. Evergreen beech forest is characteristic of the central and southern North Island and South Island, above 300 metres altitude. These montane forests have fewer species than lowland forests, and extensive areas may be dominated by a single tree species. The bush-line, usually of mountain or silver beech, is located generally between 1350 and 1500 metres.

A wide range of secondary forest types have developed since human arrival, notably kanuka forests east of the main divide, manuka and kanuka forests in northern New Zealand, and a range of broad-leaved tree and tree-fern forest types on abandoned farmland.

Cool moist climates produce an abundance of ferns in New Zealand forests, not only giant tree ferns, but also filmy ferns which clothe tree trunks, and ground ferns.

Shrublands. Natural shrublands are rare and usually occur where soil or water factors restrict forest development, such as the margins of coastal estuaries and other wetlands, and rocky bluffs. Immediately above the bushline, a narrow band of diverse shrubland often occurs, dominated by the heath Dracophyllum, shrub daisies, hebes, and alpine podocarps. The most extensive shrublands occur in the once-forested dryland of eastern New Zealand, where small-leaved sometimes spiny shrubs occur, notably matagouri (Discaria), tauhinu (Cassinia), and divaricating coprosmas. These shrublands are stages in the re-establishment of forest. Fernland, particularly bracken fern (Pteridium esculentum), once a staple Maori food, is very widespread throughout deforested New Zealand hill country. Like shrubland it serves as a nurse-bed for forest species.

Wetlands. A rise in sea-level inundated coastal valleys formed during the ice-age. This created extensive estuaries, rich in worms, molluscs and eelgrass, which are important habitats for marine birds, such as oyster-catchers and a refuge for migratory waders. In the north the estuaries support dense groves of low mangroves, while elsewhere there are extensive rush and sedge wetlands which are spawning grounds for whitebait or inanga (Galaxias spp.). The numerous rivers of New Zealand created extensive freshwater wetlands dominated by harakeke or flax (Phormium), raupo (Typha) and sedges. These have mostly been drained but are extensive in the western South Island. Numerous small swamps and lakes have been formed to the lee of sand dunes deposited along western coasts by prevailing westerly winds. Lakes, swamps and bogs made by glaciers are features of the South Island high country.

Dune lands. Coastal sand deposits were once colonised by the now threatened pingao (Desmochoenus spiralis), a sedge used for traditional Maori weavings. The areas have been stabilised by marram grass, lupins and pines, which have displaced native species, and so few remain in their natural state.

Grasslands. When Europeans arrived in the nineteenth century much of the eastern South Island was covered by short tussock grassland or silver tussock and fescue, which had become established after Maori fires removed forests. Before the Maori the only naturally occurring lowland tussock was in the dry interior of Central Otago. Pastoral farming and introduced grasses have now largely destroyed short tussock grassland. However, at higher altitudes, especially above the bush-line, extensive areas of natural tall snow tussock (Chionochloa spp.) occur.

Alpine vegetation. Large-leaved herbs, mat plants, and cushion plants occur throughout the tall tussocks, and in places dominate and form herb fields of great beauty in flower. Scree supports a range of specialised, often fleshy, drought-resistant plants. Alpine bluffs support a scattered cover of shrubs, herbs and cushion plants, adapted to extreme climate and sometimes possessing very strange form, such as the vegetable sheep (Raoulia spp, Haastia spp).

Introduced vegetation and wildlife. The New Zealand landscape is now dominated by introduced animals and plants. Over 1500 exotic plants grow wild, some (like rye-grass, browntop, gorse and sweet briar), over large areas. Although introduced plants have seldom colonised extensive areas of native vegetation, wild animals (deer, pigs, goats, possums, stoats and rats) are widespread, and some introduced birds, such as blackbirds, occur everywhere. Urban vegetation is largely exotic and domestic stock dominate agricultural areas throughout the lowlands.

Introduced plants and animals have greatly increased the diversity of species in New Zealand. However, their increase has been associated with a decrease in the area dominated by native species. Today a large number of native species are very rare and seldom seen. Some of these are ancient and stamp uniqueness on New Zealand as a living museum. Urgent measures are needed to ensure the healthy survival of this unique heritage of international importance.

One uniform time is kept throughout New Zealand. This is the time 12 hours ahead of Co-ordinated Universal Time, and is named New Zealand Standard Time (N.Z.S.T.). It is an atomic standard, and is maintained by the New Zealand Time Service of the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research (DSIR). One hour of daylight saving, named New Zealand Daylight Time, which is 13 hours ahead of Co-ordinated Universal Time, is observed from 2 a.m. (N.Z.S.T.) on the last Sunday in October, until 2 a.m. (N.Z.S.T.) on the first Sunday in March the next year. Time kept in the Chatham Islands is 45 minutes ahead of that kept in New Zealand.

1.1 New Zealand Geographic Board/DOSLI.

1.2 Department of Scientific and Industrial Research.

1.3 New Zealand Meteorological Service.

1.4 Department of Conservation.

1.5 Department of Internal Affairs.

New Zealand Atlas. Ward, I., ed. Government Printer, 1976.

Catalogue of Maps. Department of Survey and Land Information.

Gage, M. Legends in the Rocks—An Outline of New Zealand Geology. Whitcoulls, 1980.

Lillie, A. R. Strata and Structure in New Zealand. Tohunga Press, 1980.

Riddolls, P. M. New Zealand Geology—Containing Geological Maps of New Zealand 1:2 000 000. DSIR, Science Information Publishing Centre, 1987.

Searle, E. J. City of Volcanoes. 2nd edition. Longman Paul, 1981.

Smith, I. E. M., ed. Late Cenozoic Volcanism in New Zealand. Bulletin 23, Royal Society of New Zealand, 1986.

Soons, J.; Selby, M., eds. Landforms of New Zealand. Longman Paul, 1982.

Speden, I. G.; Keyes, I. W. Illustrations of New Zealand Fossils. DSIR Information Series 150, 1981.

Stevens, G. R. Lands in Collision: Discovering New Zealand's Past Geography. DSIR Information Series 161, 1985.

Stevens, G. R. New Zealand Adrift: The Theory of Continental Drift in a New Zealand Setting. A. H. and A. W. Reed, 1980.

Stevens, G. R. Rugged Landscape. A. H. and A. W. Reed, 1974.

Suggate, R. P.; Stevens, G. R.; Te Punga, M. T., eds. The Geology of New Zealand. 2 vols. Government Printer, 1978.

Thornton, J. Field Guide to New Zealand Geology. Reed Methuen, 1985.

Williams, G. J. Economic Geology of New Zealand. AusIMM Monograph Series 4, 1974.

An Encyclopedia of New Zealand. McLintock, A. H., ed. Vol. 1. Government Printer, 1966.

Johnson, K. F. Bibliography of New Zealand Meteorological Service Publications 1892–1985. New Zealand Meteorological Service, 1986.

New Zealand Atlas. Ward, I., ed. Government Printer, 1976.

The Meteorological Service publishes monthly summaries of:

Climate Observations (Misc. Pub. 109) and Rainfall Observations (Misc. Pub. 110) annually; Climate Observations which are updated every 10 years, e.g. 1980 (Misc. Pub. 177); Rainfall Normals (averages) for 30-year periods, e.g. 1951–1980 (Misc. Pub. 185); Sunshine Normals (averages) for 30-year periods, e.g. 1951–1980 (Misc. Pub. 186); and Temperature Normals (averages) for 30-year periods, e.g. 1951–1980 (Misc. Pub. 183). The service also produces regional climatologies (Misc. Pub. 115), maps and many other publications.

Enting, B.; Molloy, L. The Ancient Islands. Port Nicholson Press, 1982.

Kuschel, G., ed. Bio-geography and Ecology in New Zealand. W. Junk, 1975.

Salmon, J. J. The Native Trees of New Zealand. Reed Methuen, 1980.

Stevens, G. R. Lands in Collision: Discovering New Zealand's Past Geography. DSIR, 1985.

See also the bibliography, Books about New Zealand, at the back of this volume.

Table of Contents

Archaeology and oral tradition are the main sources for present-day knowledge of the origins and way of life of the early Polynesian inhabitants of the islands in the Pacific which became known as Aotearoa (literally ‘the land of the long white cloud’). Archaeology encompasses physical anthropology, linguistic evidence, and traditional accounts, as well as sophisticated examination of the tangible relics of human occupation. Oral traditions did not simply describe what happened. They also explained and justified past events, and were often the accounts of the victors in inter-tribal conflict. Both are of much value to historians, and also pose problems. Statements about New Zealand's Polynesian past must therefore remain tentative.

The ancestors of Aotearoa's earliest inhabitants are thought to have reached the Western Pacific some 4000 years ago, and gradually made their way along the Melanesian chain of islands. Long ocean journeys became possible for them with the introduction of the sail and the invention of the outrigger, which stabilised canoes in rough seas. They reached Fiji and Tonga by about 1000 B.C., and in this area many of the distinctive features of Polynesian social organisation and language developed. About 2000 years ago there was a further eastward movement to the Society, Marquesas, and Cook Islands, at the heart of the Polynesian triangle. Probably from this region, the most isolated parts of Polynesia were settled—New Zealand, Hawaii, and Easter Island. There has been much controversy as to the nature of, and reasons for, undertaking such long ocean voyages. Some would have been accidental, the result of canoes being blown off shore. At other times, refugees from defeated tribes or over-populated areas may well have set off into the unknown, confident that they were likely to make a safe landfall somewhere. Knowledge of stars, currents, bird migrations, and the signs of distant land was such that the possibility of controlled journeys over even thousands of kilometres cannot be discounted. The canoe or canoes which brought the first successful colonists to Aotearoa must have carried men and women, dogs, rats, vegetables for cultivation, and a variety of tools and ornaments for practical use and as models for those to be made subsequently. Such a well-equipped expedition is unlikely to have been completely accidental.

Polynesian people, known today as Maori, have lived in New Zealand since about the eighth century A.D. They came in one or more groups from the same general area of eastern Polynesia, known as Hawaiki. There are traditions of numerous voyages from Hawaiki, and of a number of famous canoes, whose occupants were the founders of tribal groupings which remain distinctive today. Some of these stories probably refer to migrations within New Zealand; a few to voyages elsewhere in Polynesia. After the initial period of settlement there were probably few or no continuing contacts with the outside world. Maori culture developed characteristics which reflected both its Polynesian roots and its new physical environment.