Table of Contents

The New Zealand Official Yearbook seeks to present as completely as possible within one volume a wide range of information on the administration and national economy of New Zealand, as well as on social aspects. In the selection and presentation of material there is kept in mind the use of the Official Yearbook not only as a standard reference work by the general public, but also as a source of material for students and research workers. Information on New Zealand is being increasingly sought by administrators and universities overseas, and the Official Yearbook now goes to over 70 countries. This is a natural development as international relationships grow and the Official Yearbook helps present New Zealand to the world in which this country has expanding interests.

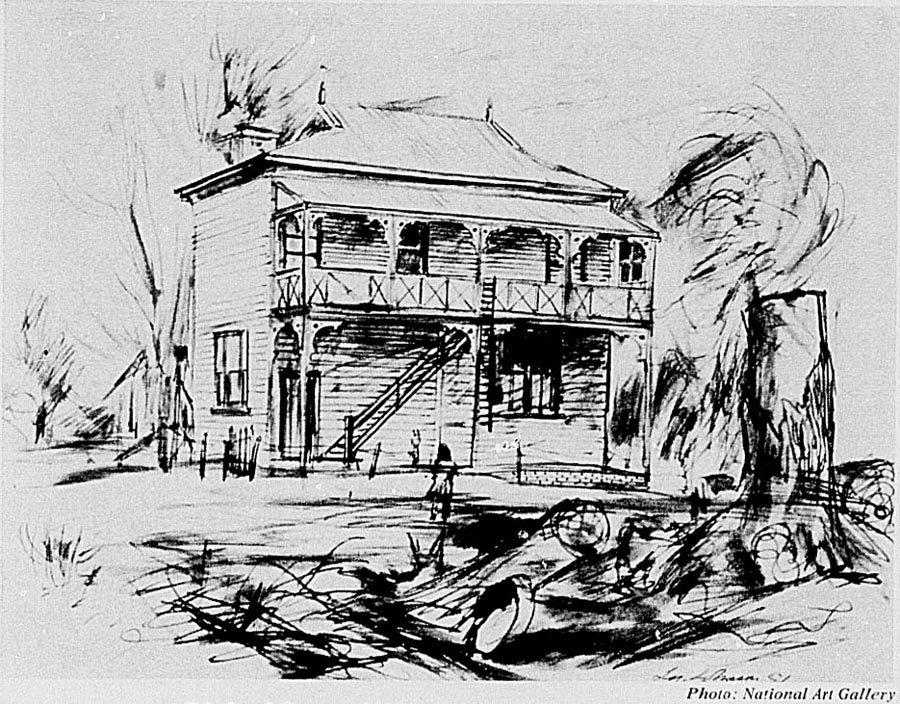

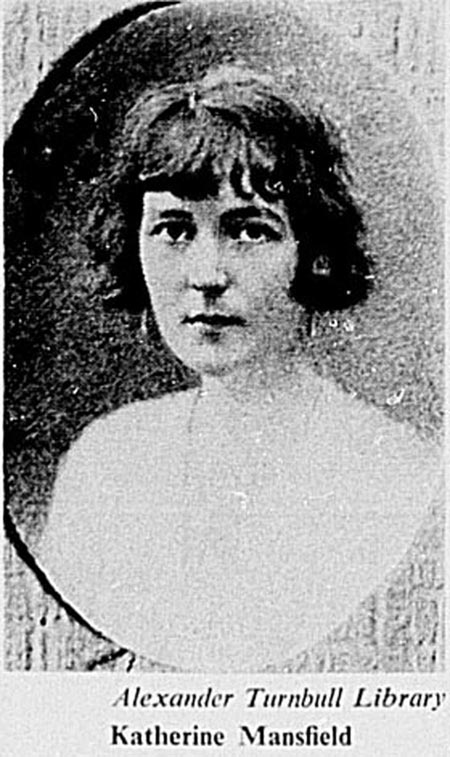

In this issue there is a comprehensive section on the arts in New Zealand covering the visual arts, literature, music and opera, drama and ballet, support of the arts, and a select Bibliography. A widespread interest has developed for this information, both within New Zealand and overseas.

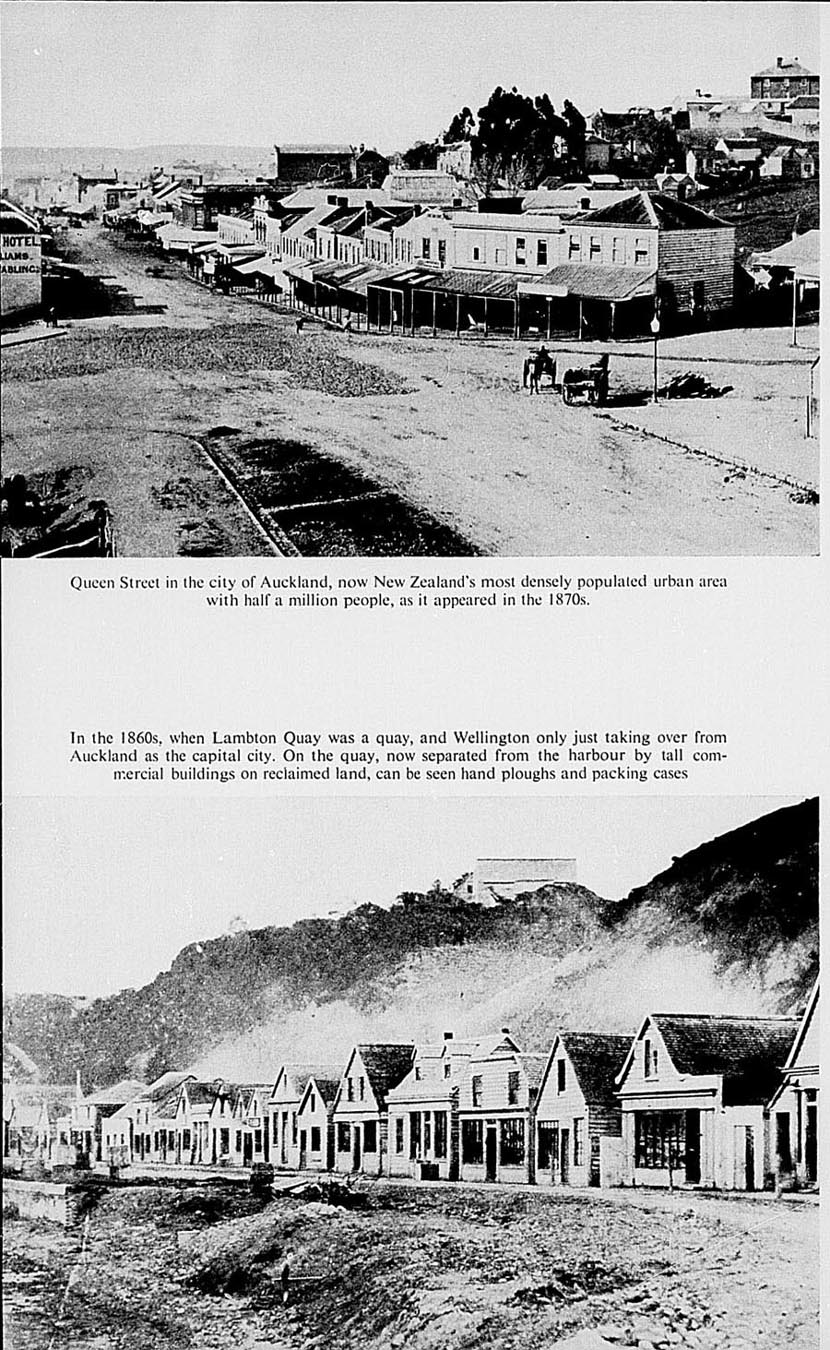

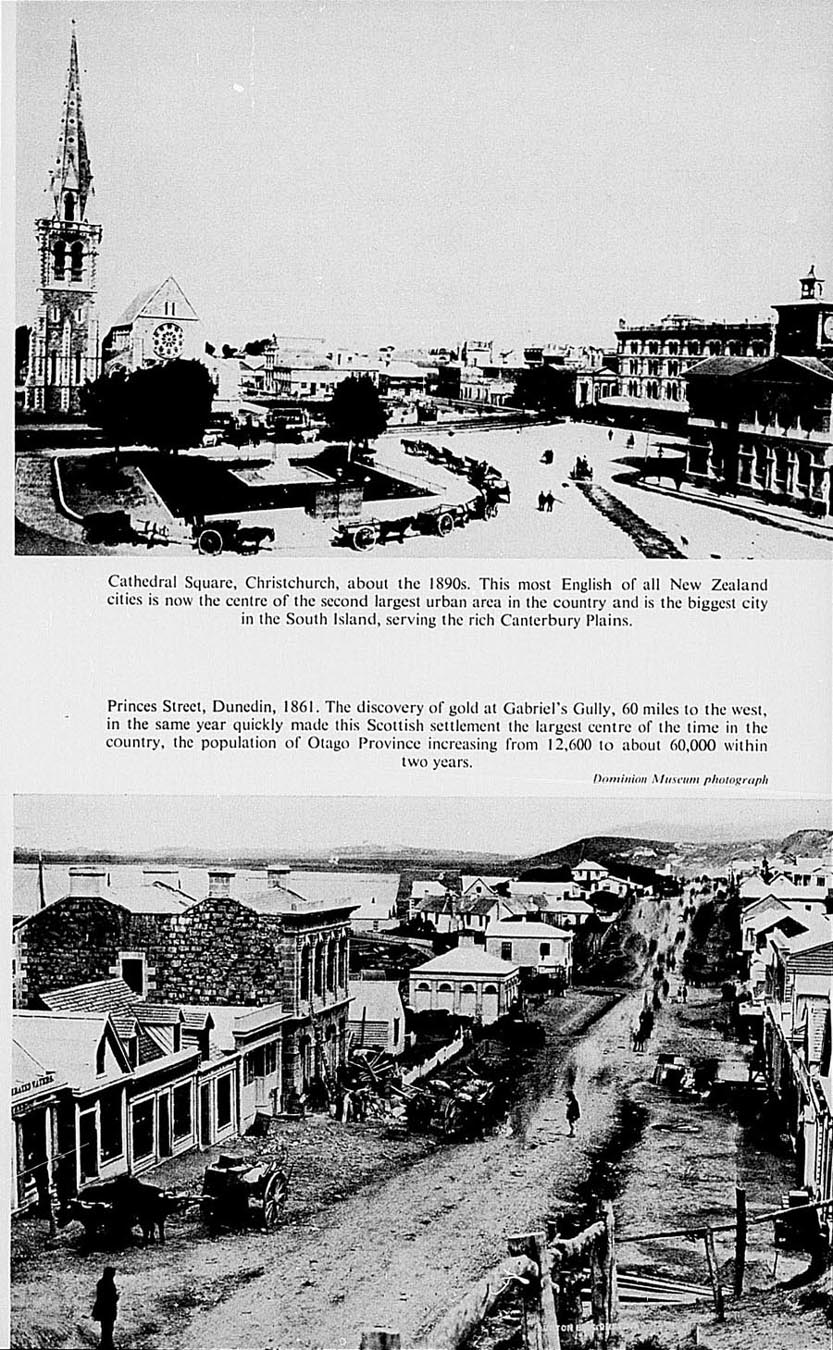

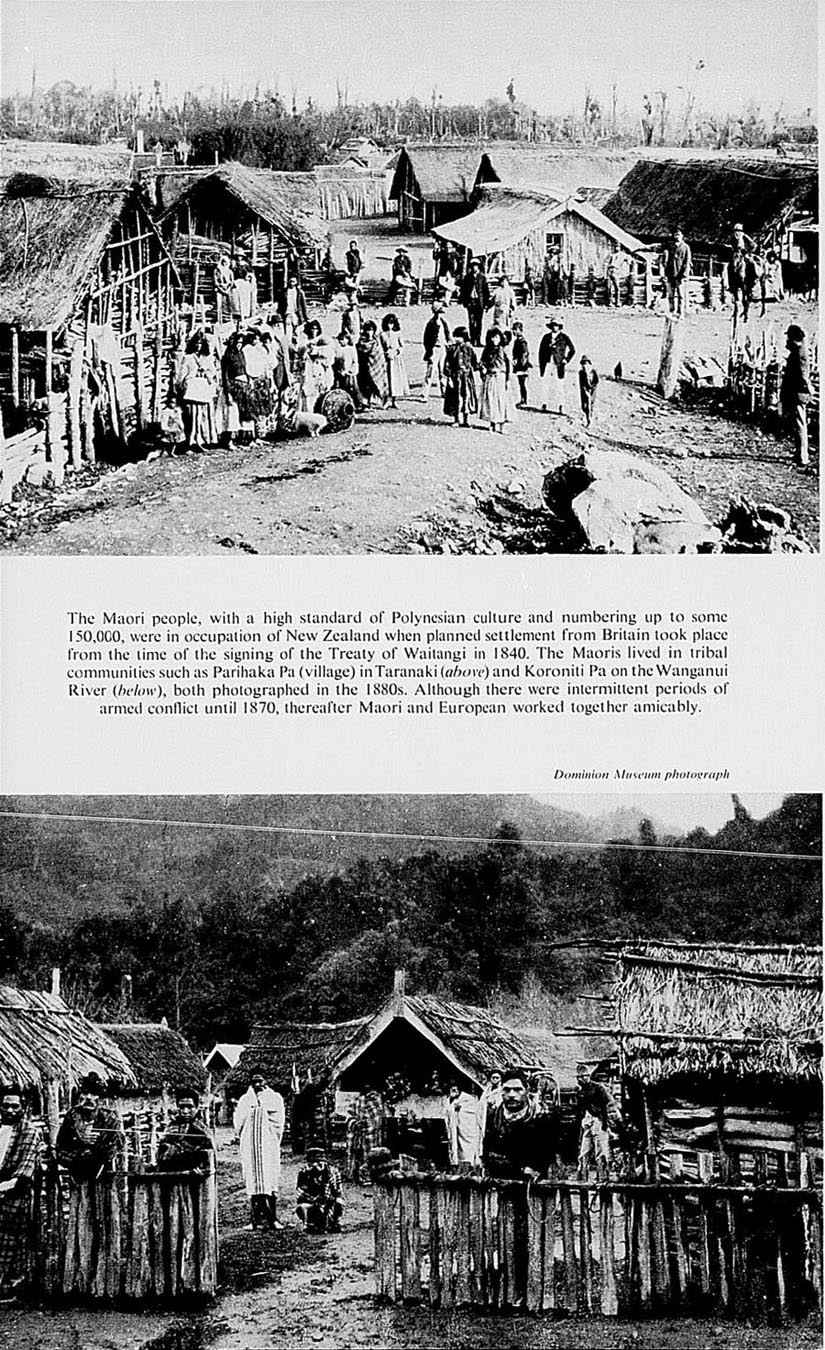

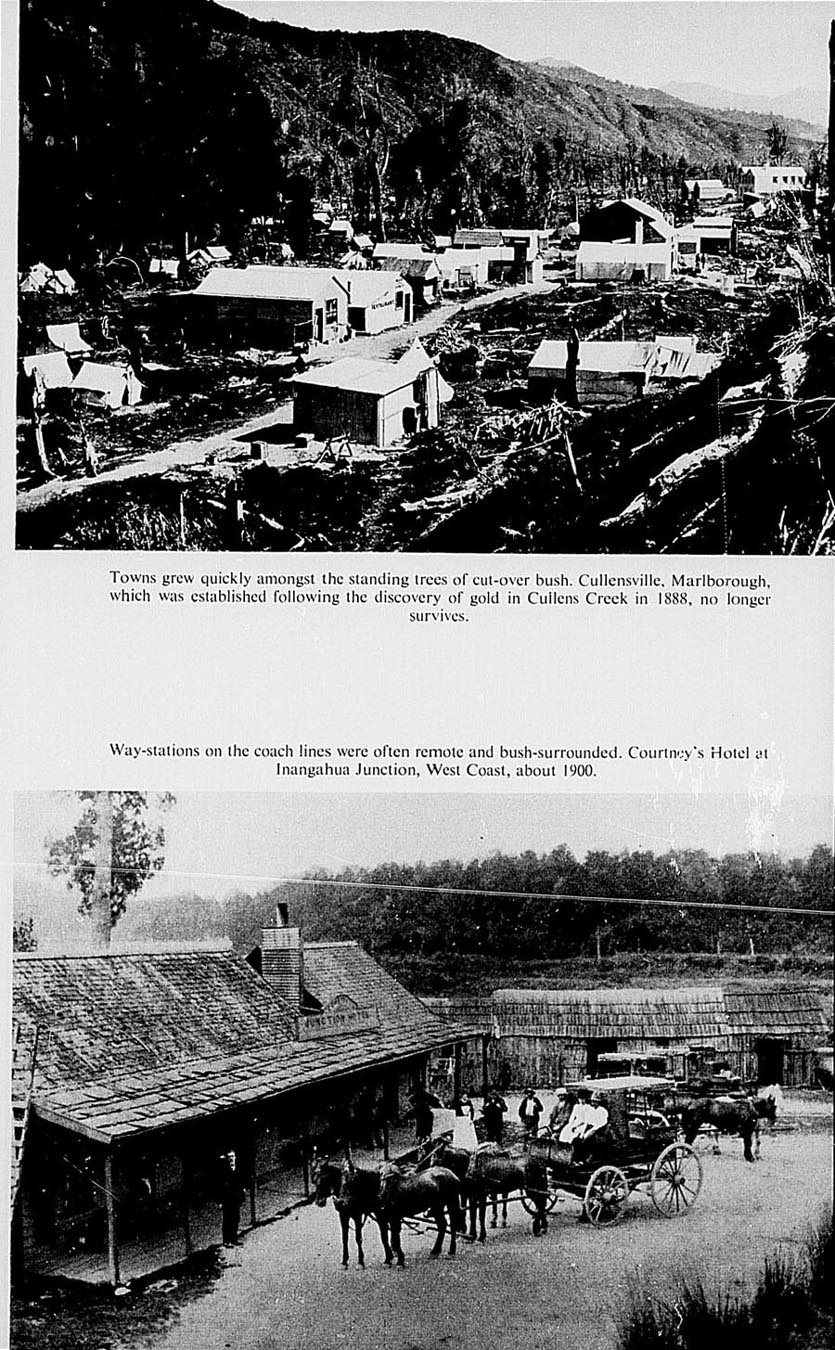

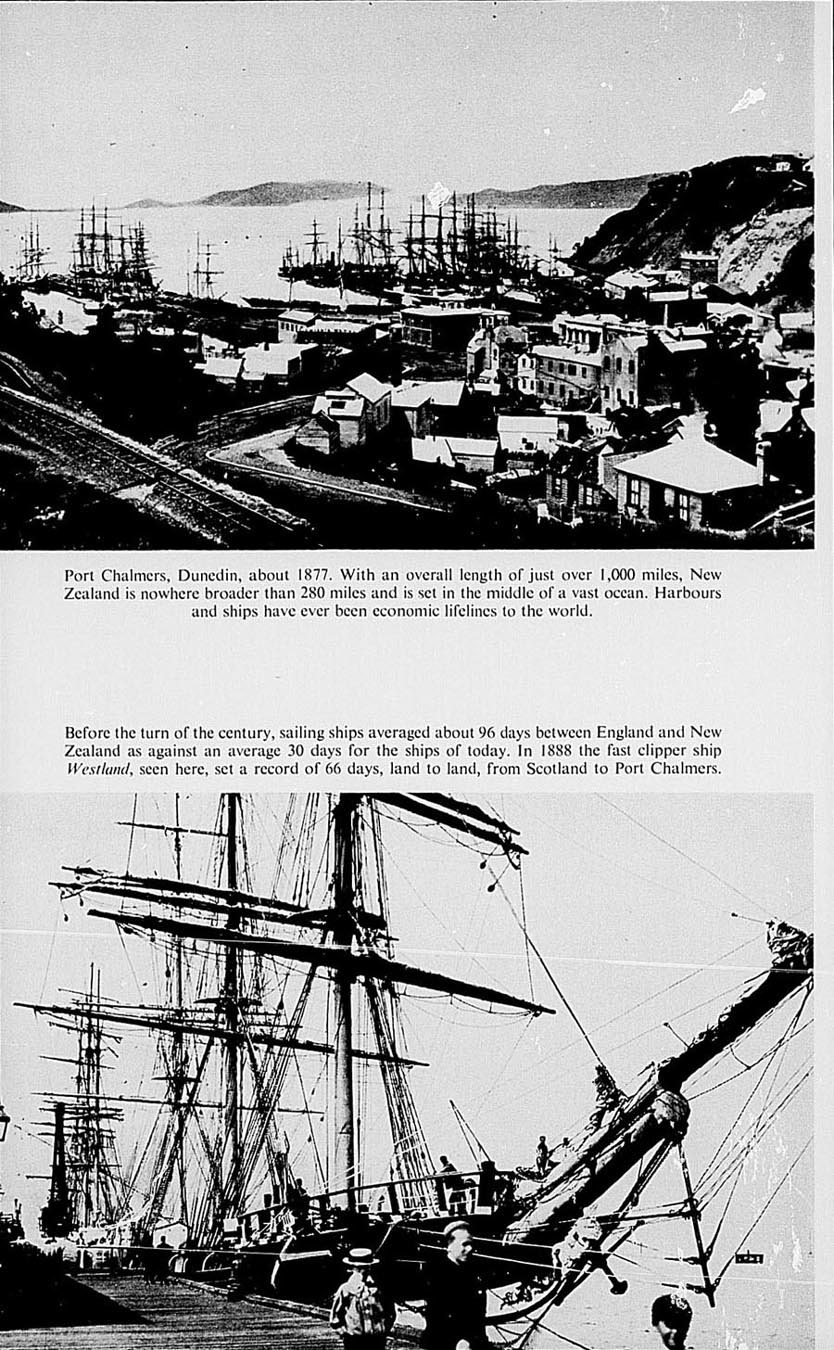

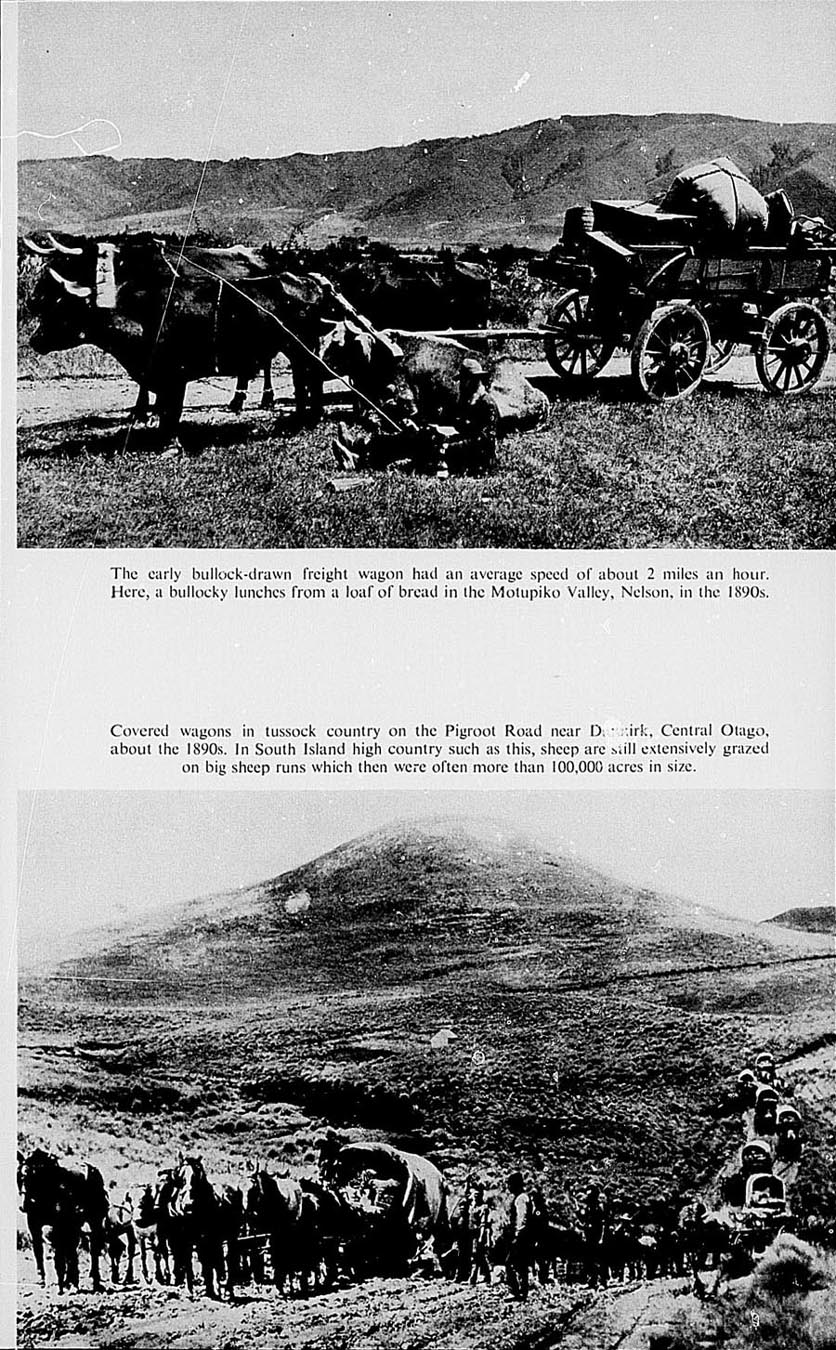

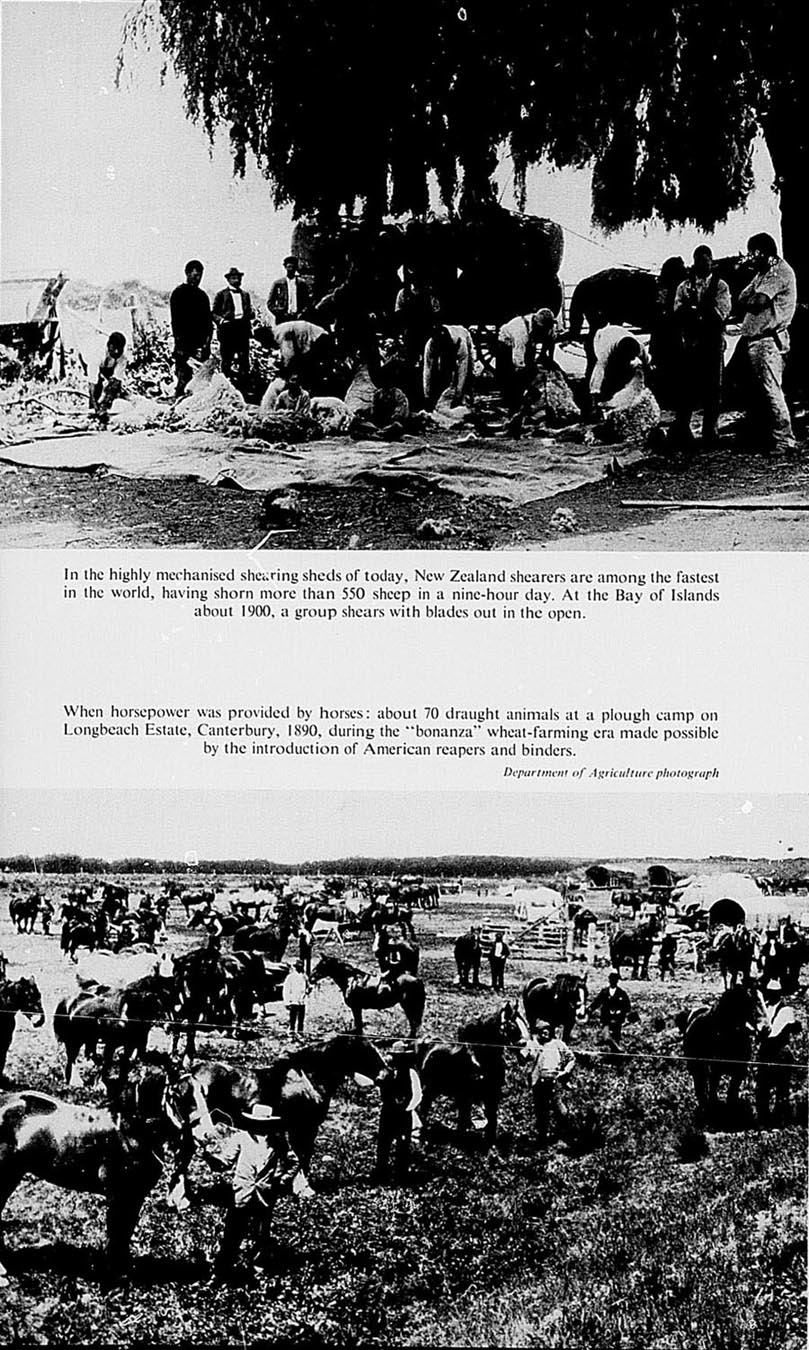

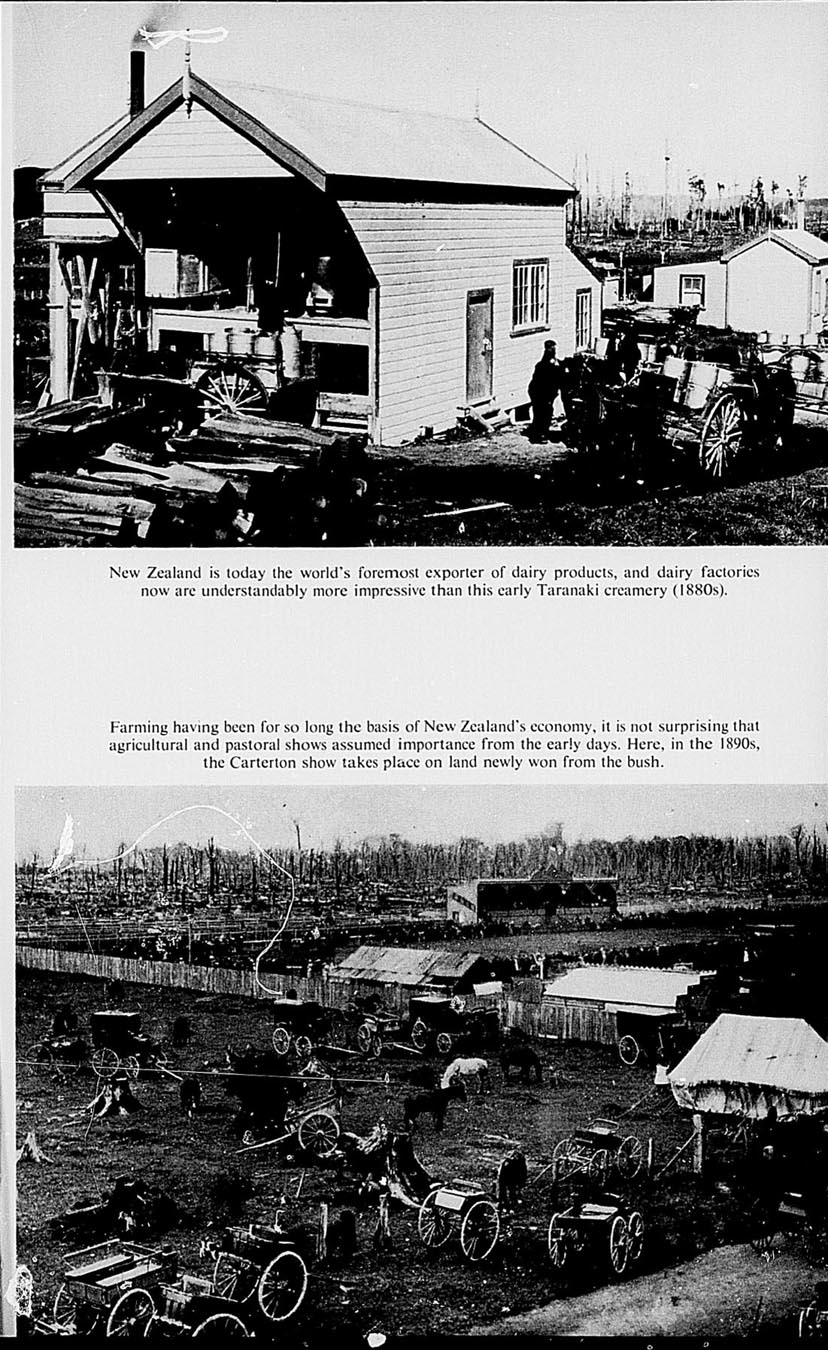

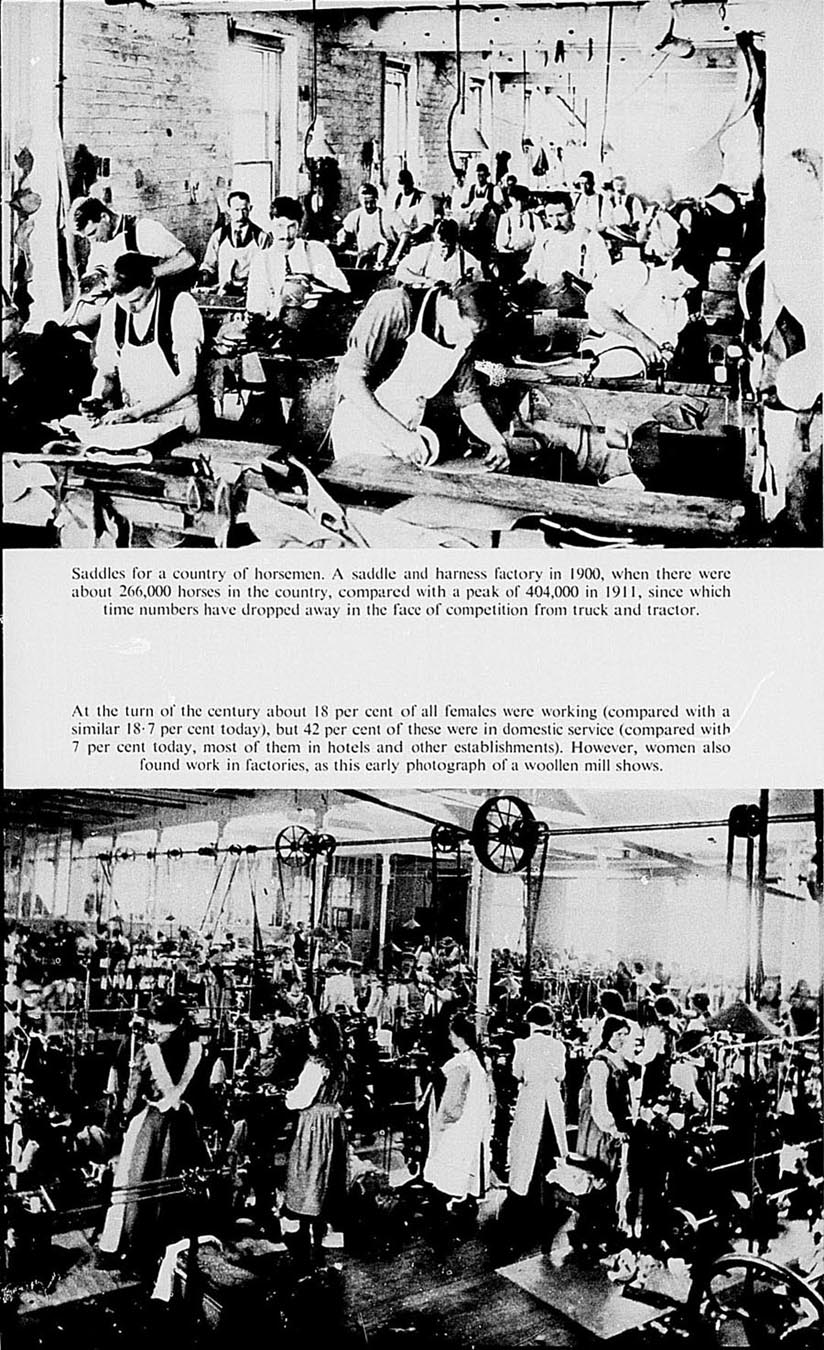

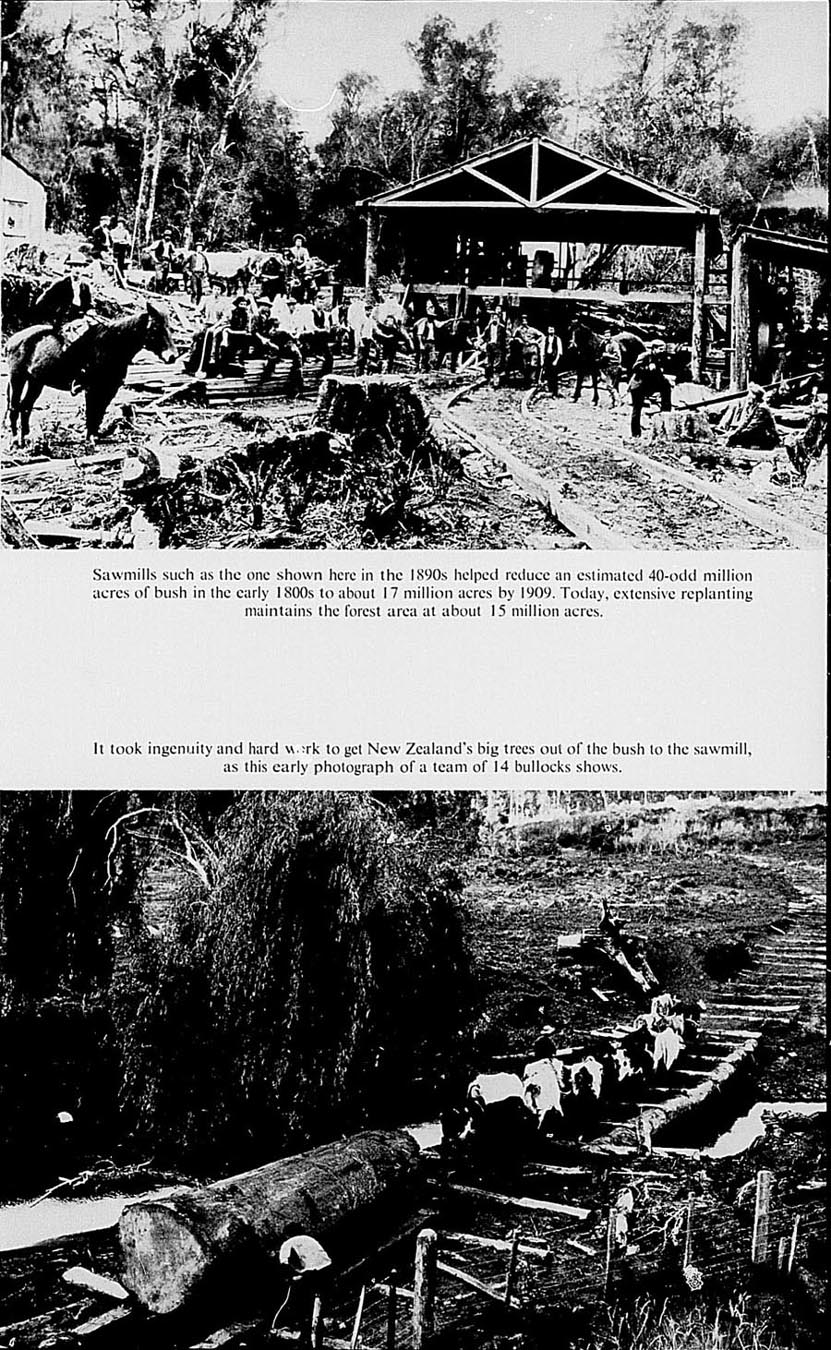

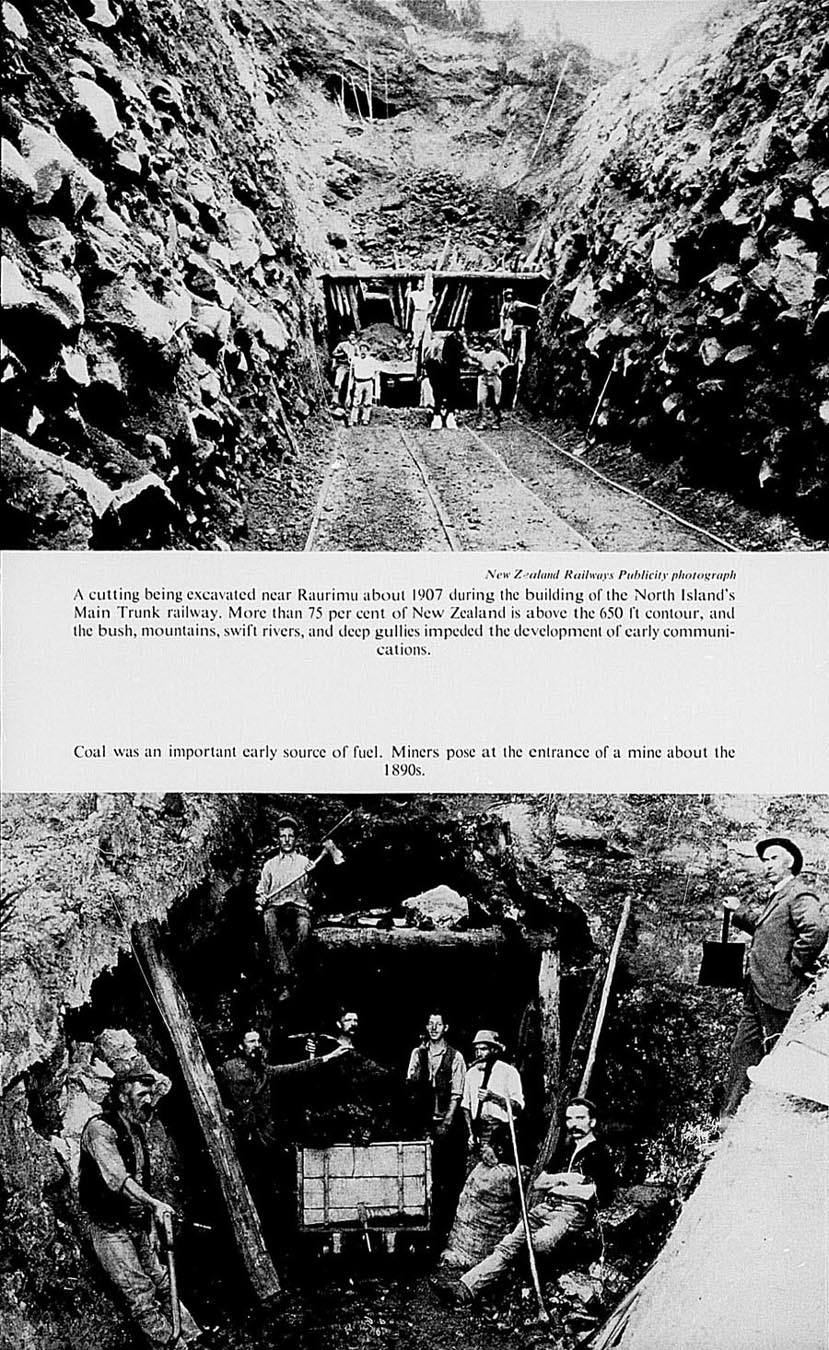

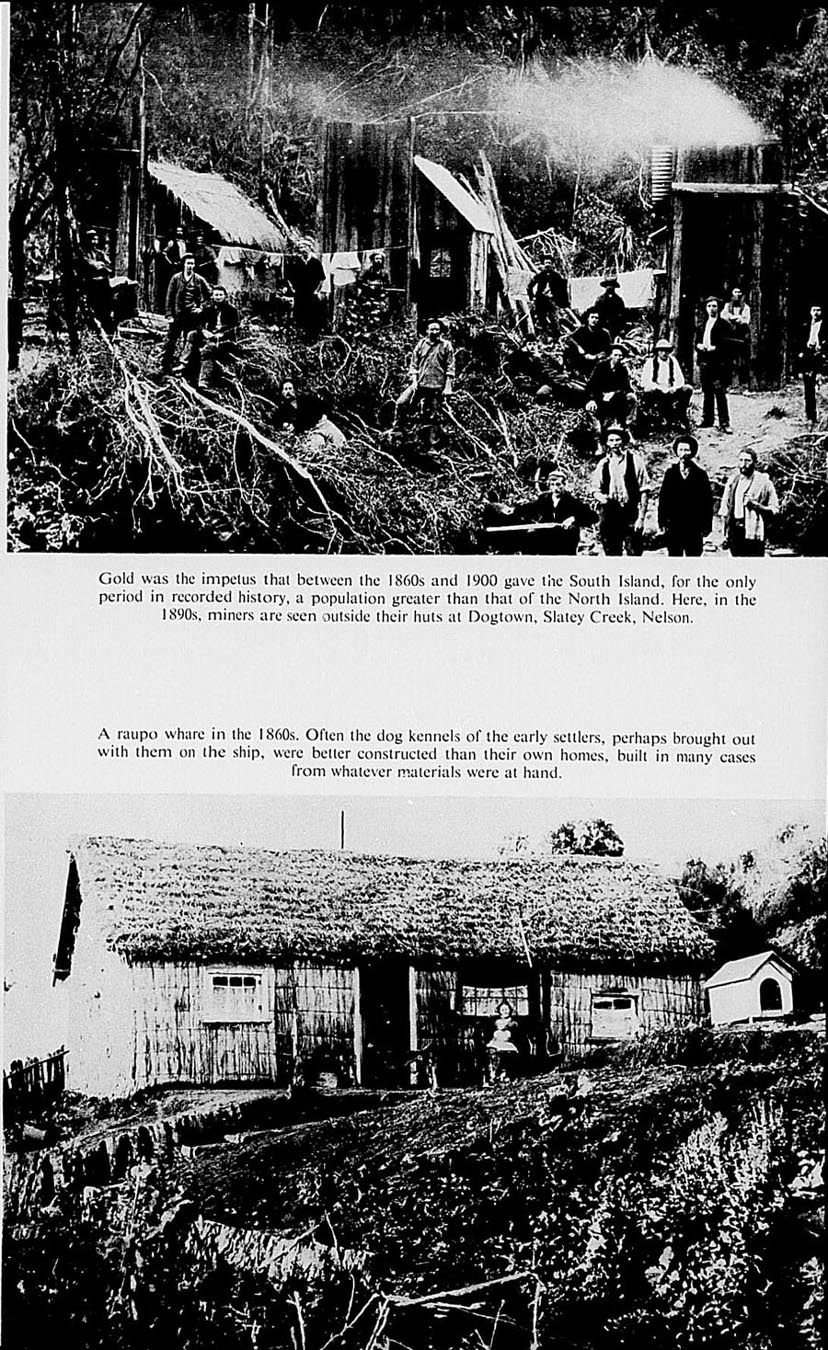

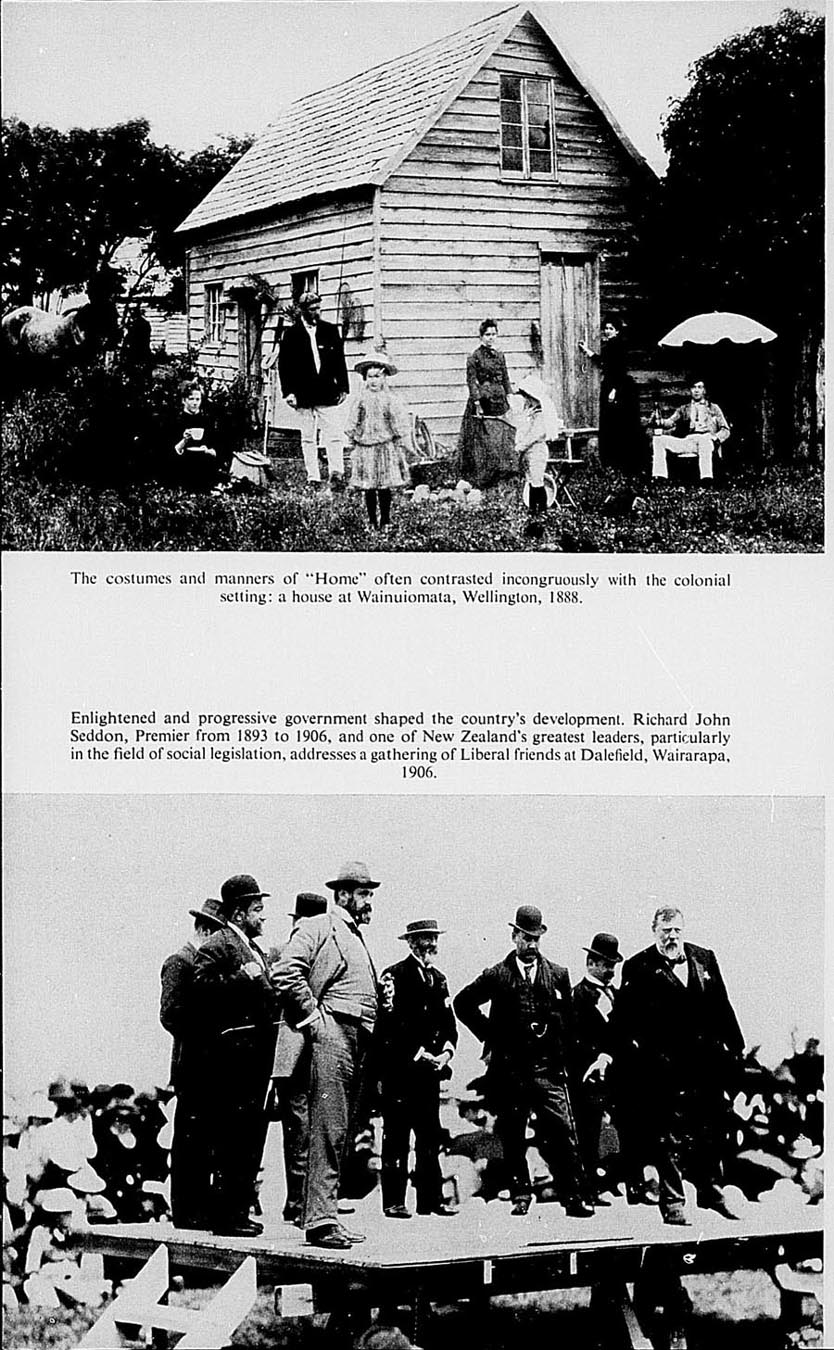

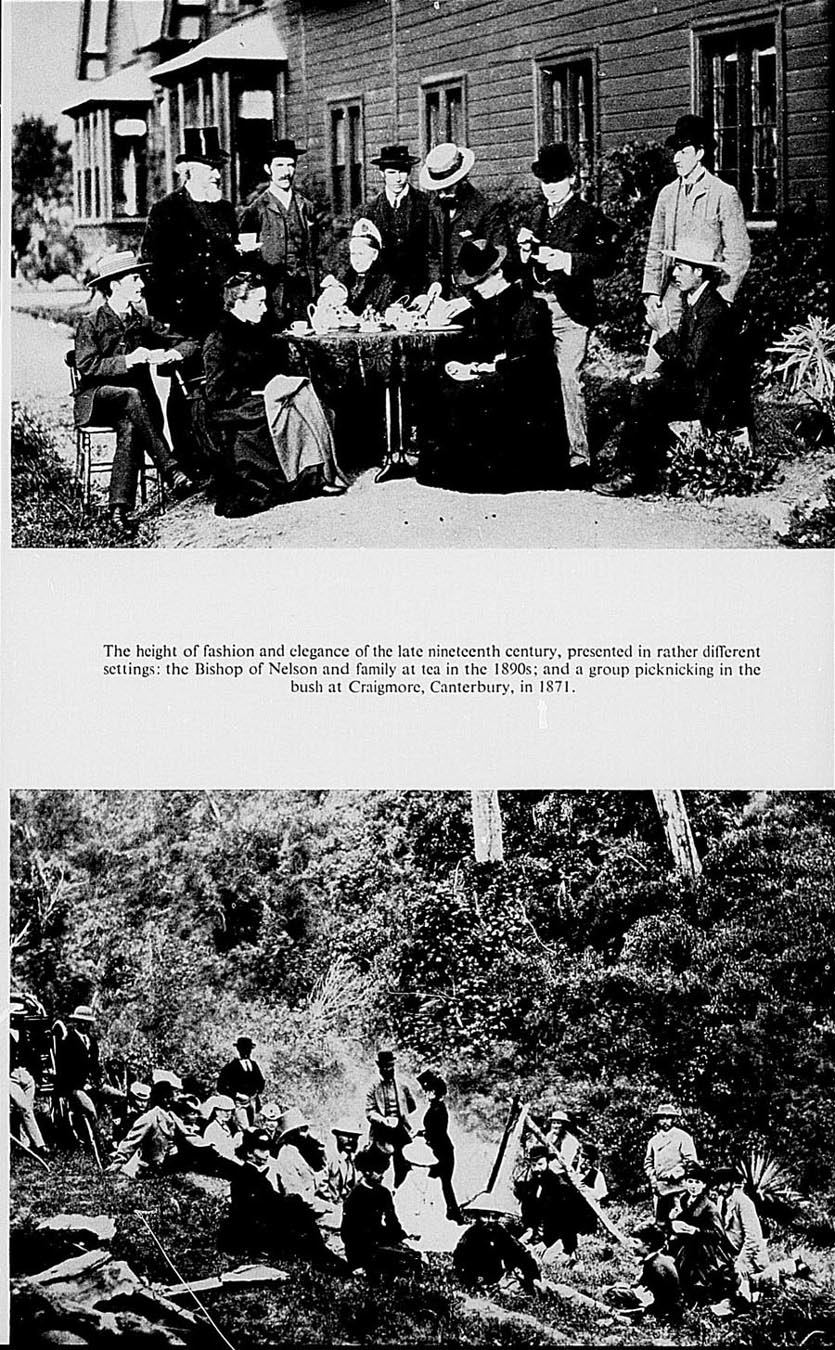

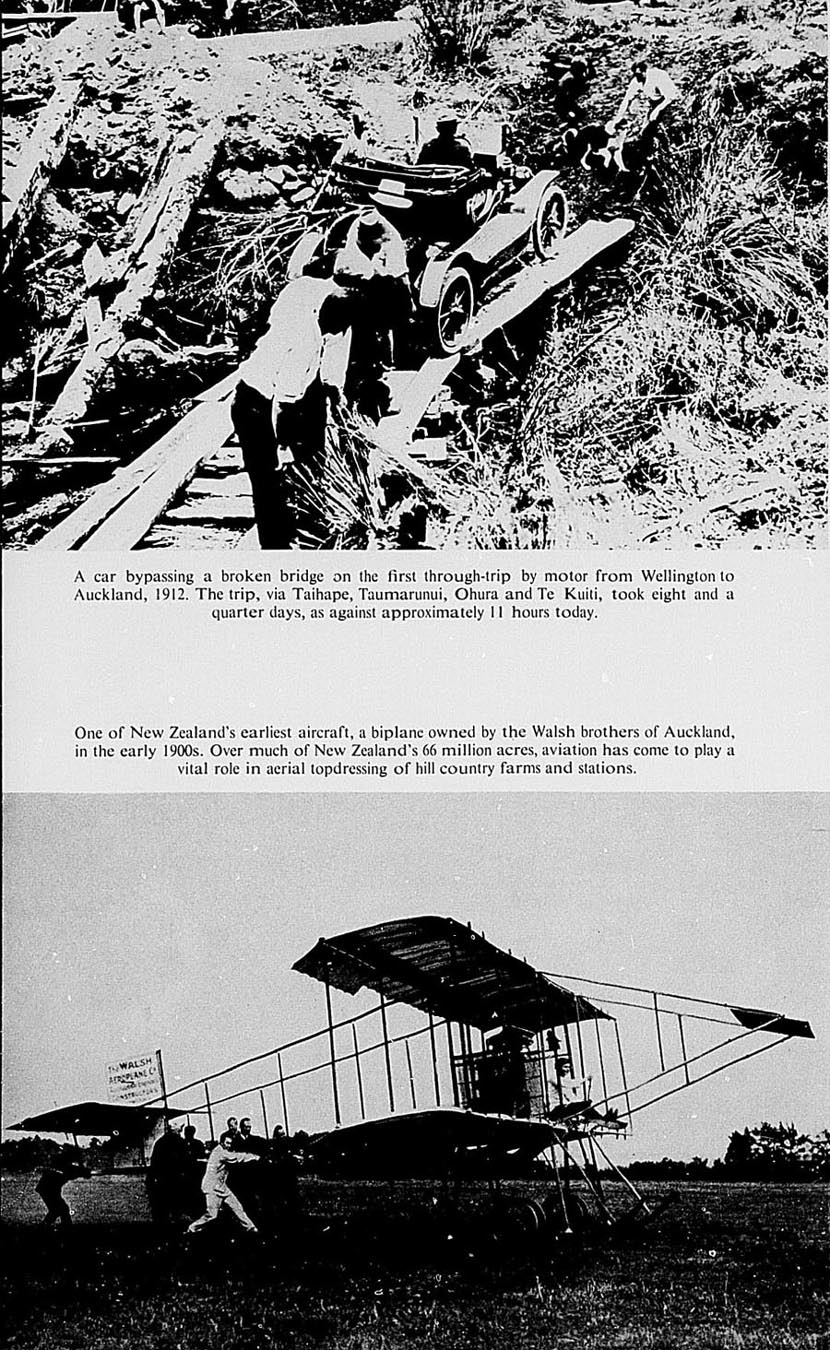

The photographic section features pioneer New Zealand with illustrations covering the period from about 1860 to 1914. It supplements other background information in the Yearbook relating to the country's development, which, in a span of 100 years has been fairly dramatic.

Acts of Parliament and the Departments of the Government of New Zealand responsible for their administration are listed in Section 41.

In line with the policy decision of the Department of Statistics to substitute statistical areas for provincial districts, many of the tables show the new classification; the main effect here is to show the former Auckland provincial district as four statistical areas as described on page 60.

I desire to express my appreciation to officers of this and other Government Departments for their assistance in preparing material and to the Government Printer and his staff for cooperation in the printing of this volume. My thanks for their comprehensive contribution to the production of the Yearbook are extended to Mr J. B. McKinney, M.A., ADMIN. PROF., Editor of Publications, and members of the Editorial Branch and Statistical Draughting Unit of the Department of Statistics.

GOVERNMENT STATISTICIAN

Department of Statistics, Wellington, 15 July 1964.

Maps

General Map of New Zealand and Island Territories Inside Back Cover

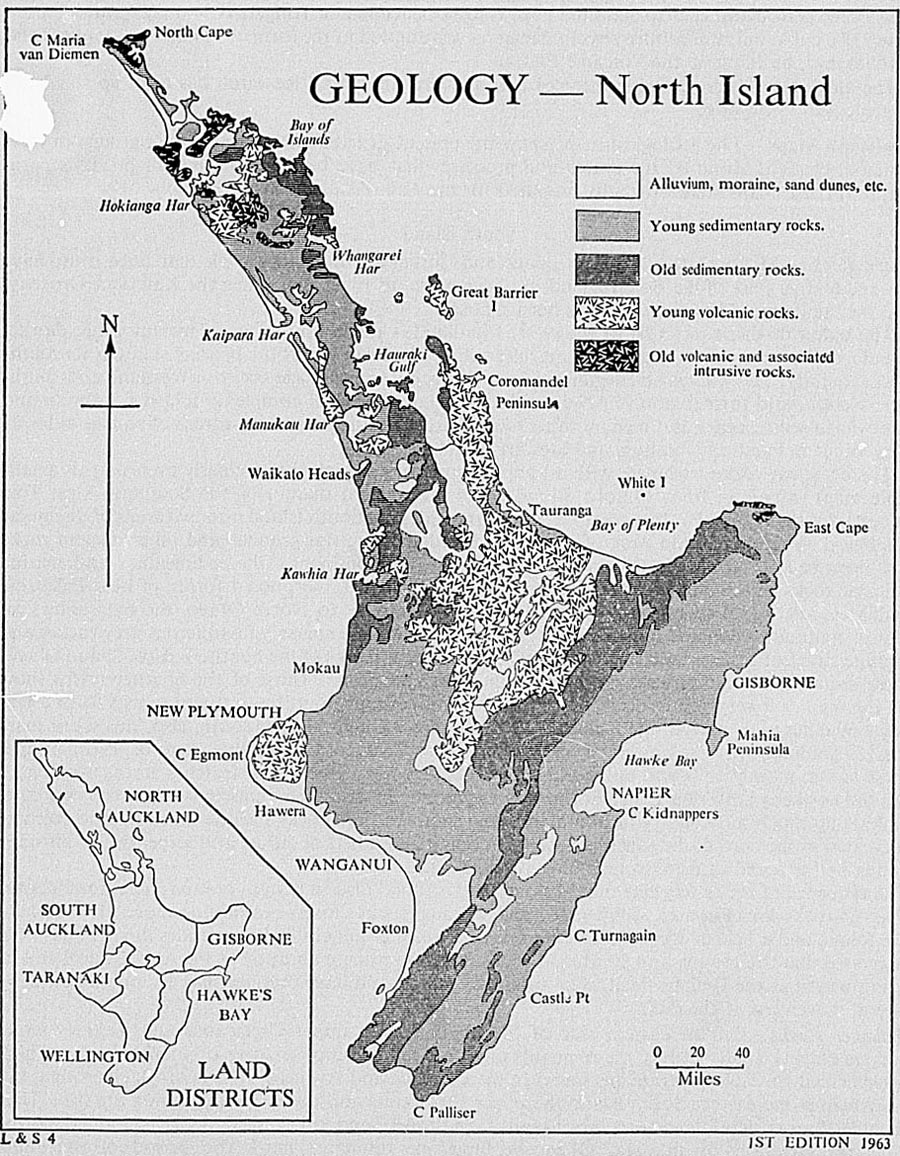

Geology – North Island 10

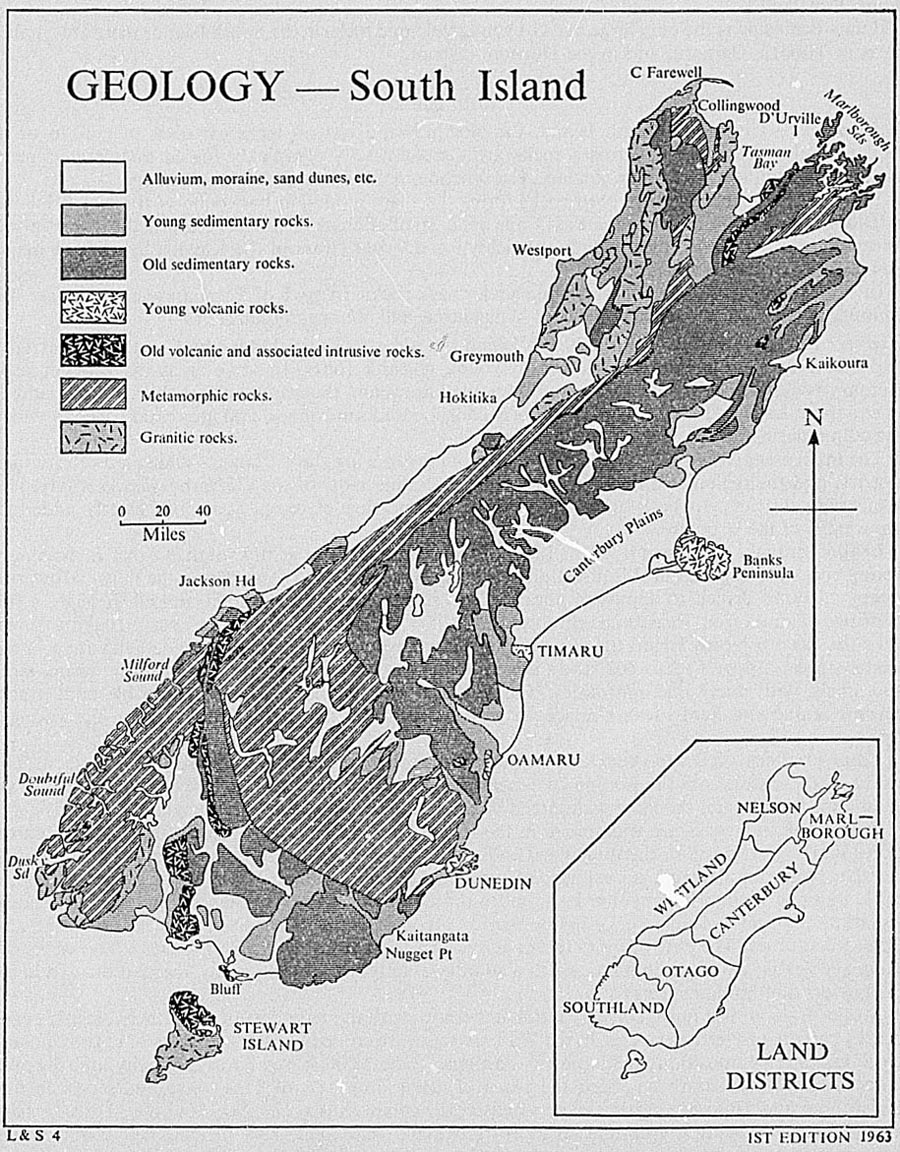

South Island 11

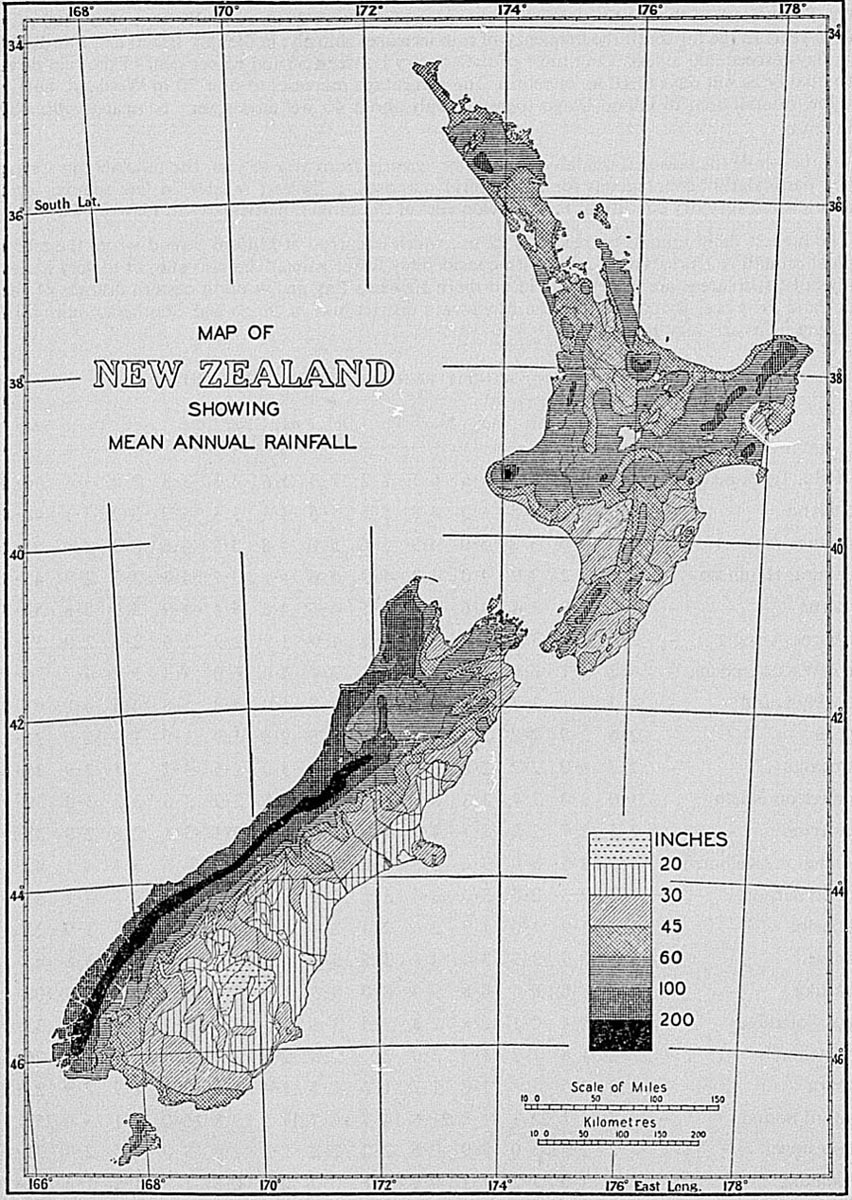

Mean Annual Rainfall 18

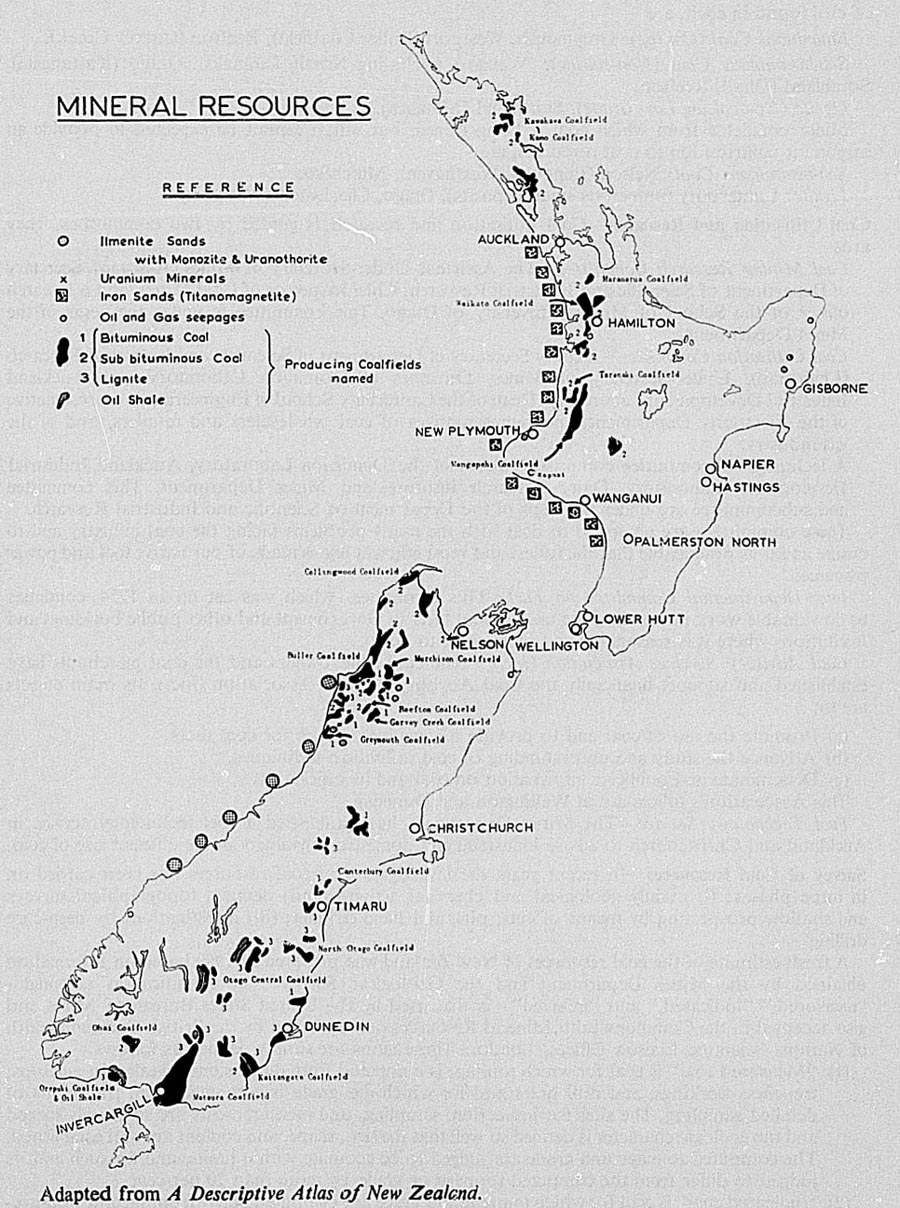

Mineral Resources 483

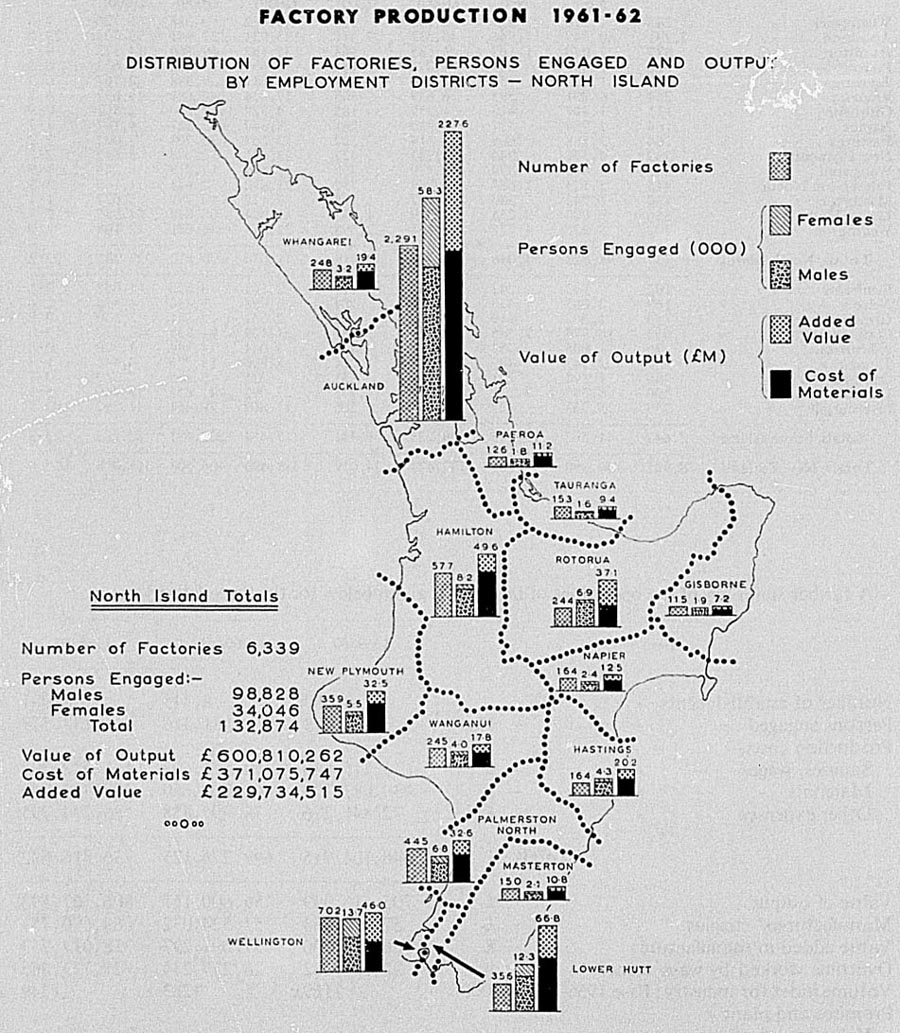

Factory Production – North Island 502

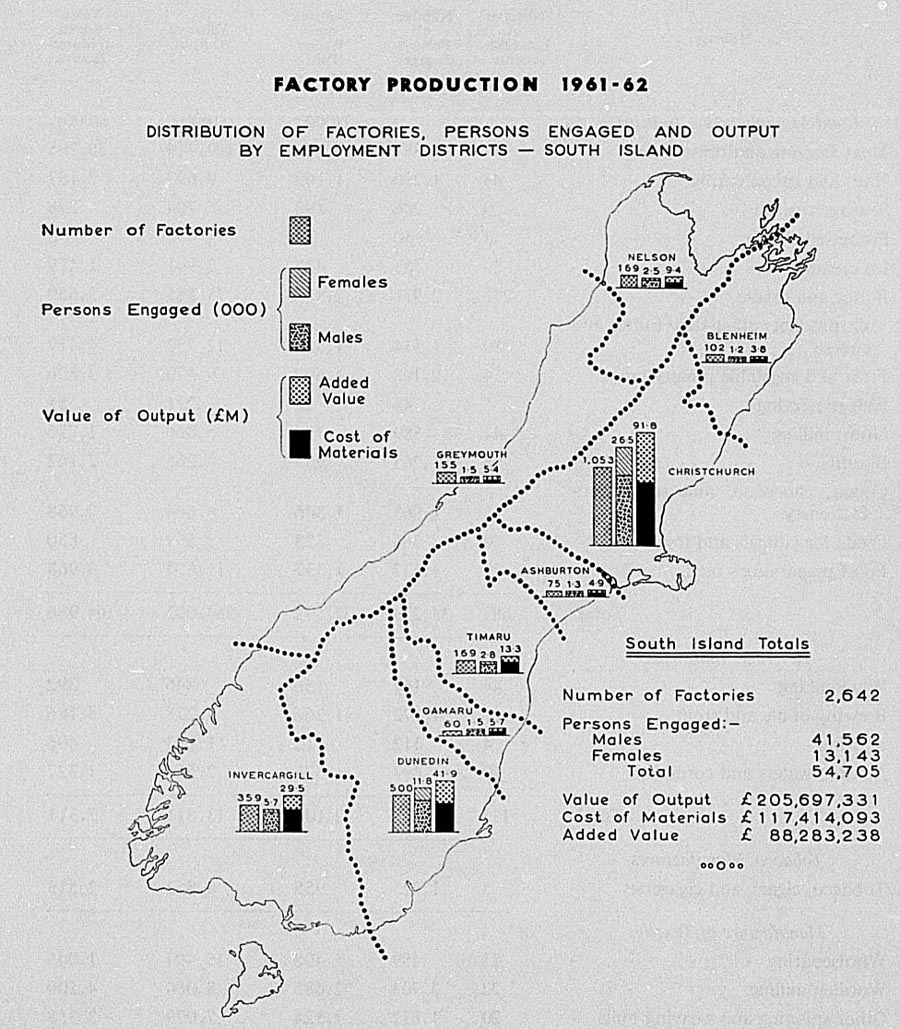

South Island 503

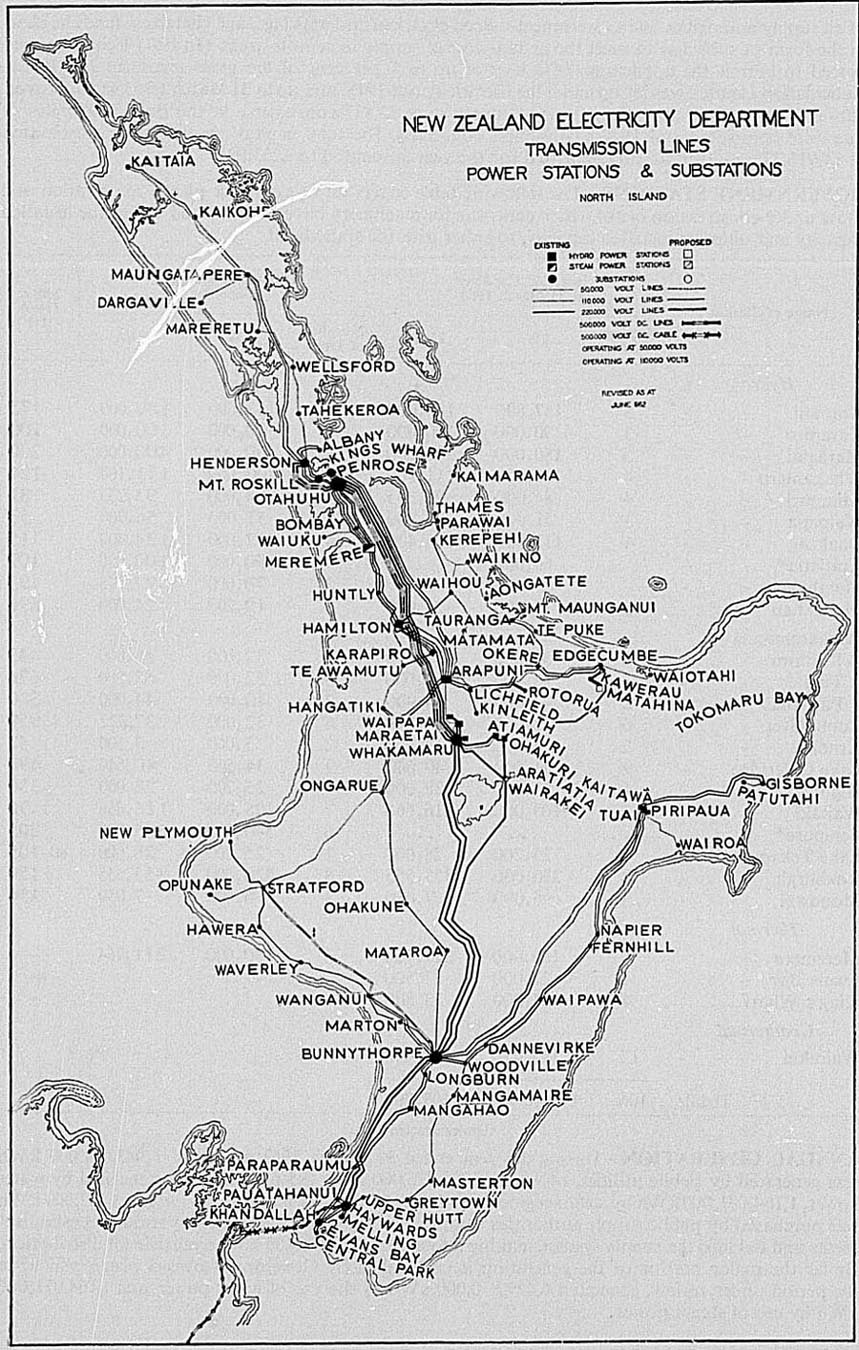

Electric Power Stations and Transmission System – North Island 574

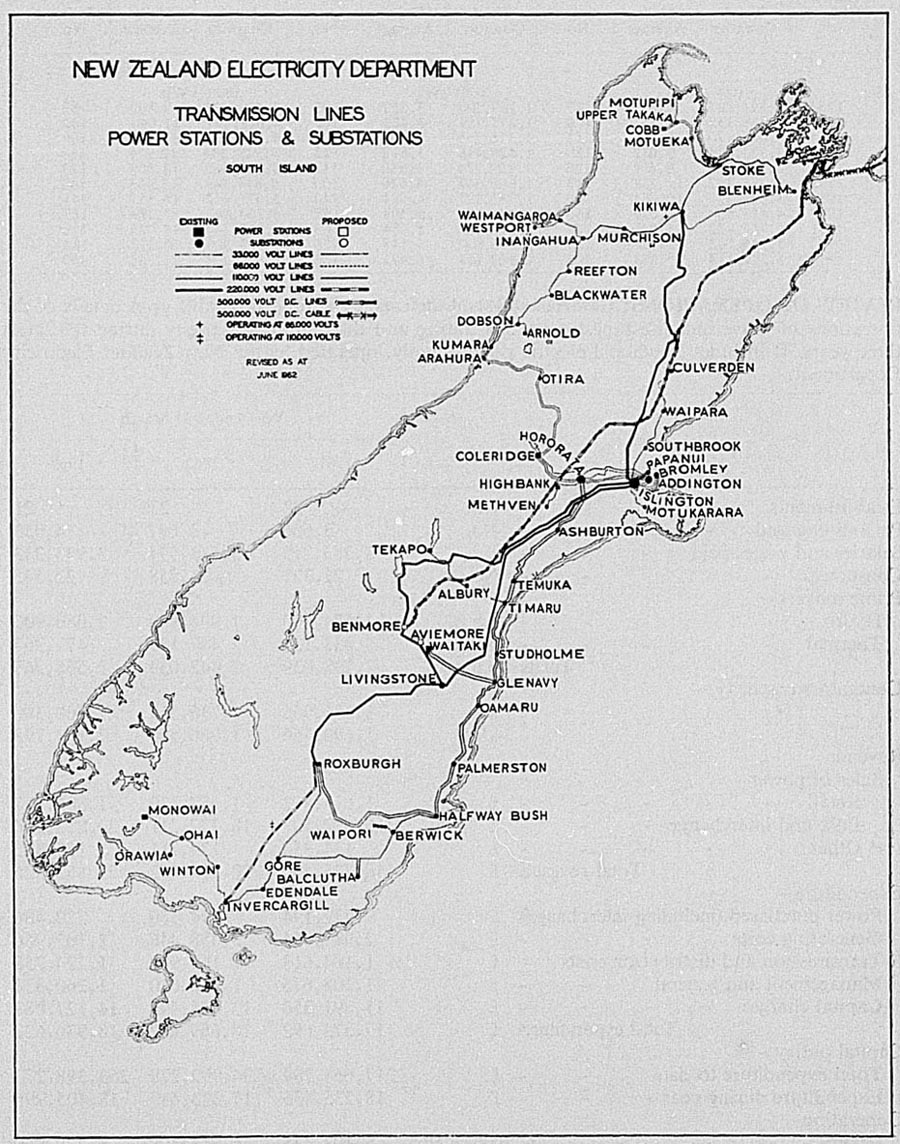

South Island 575

Diagrams

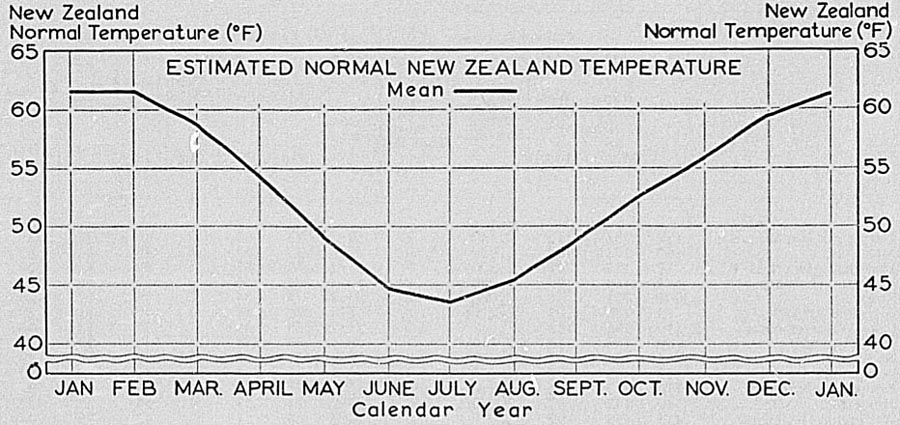

Seasonal Temperature Pattern 22

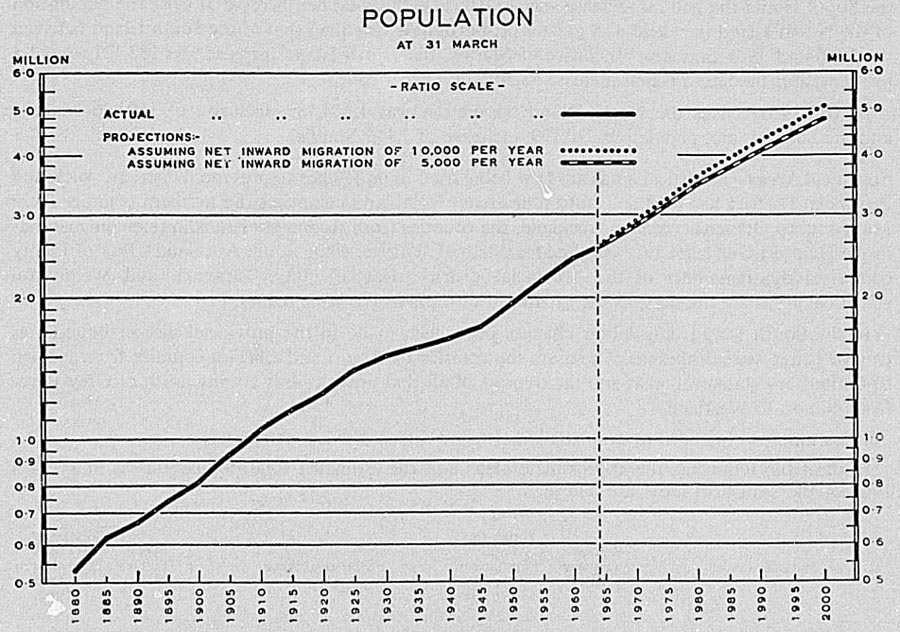

Population 59

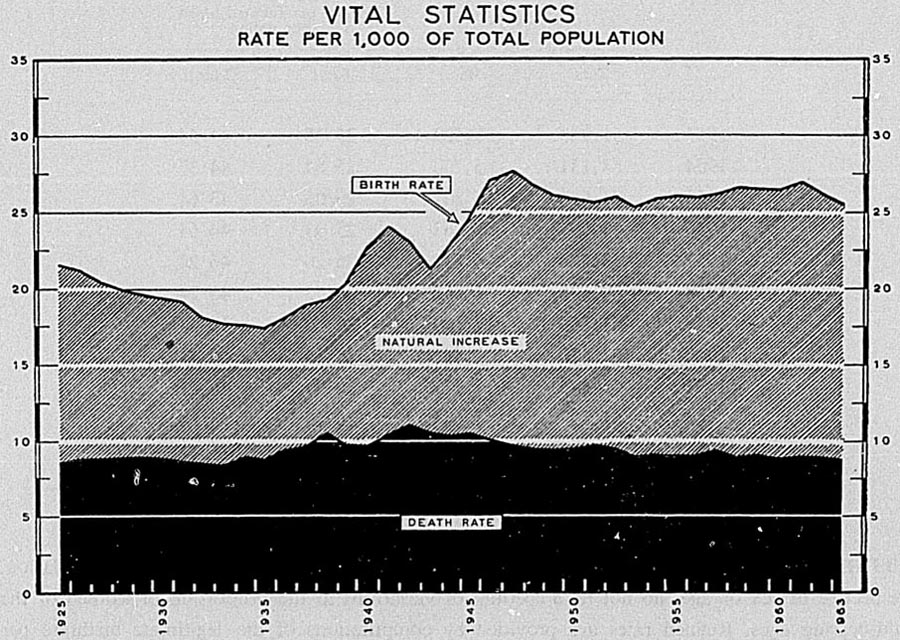

Vital Statistics 91

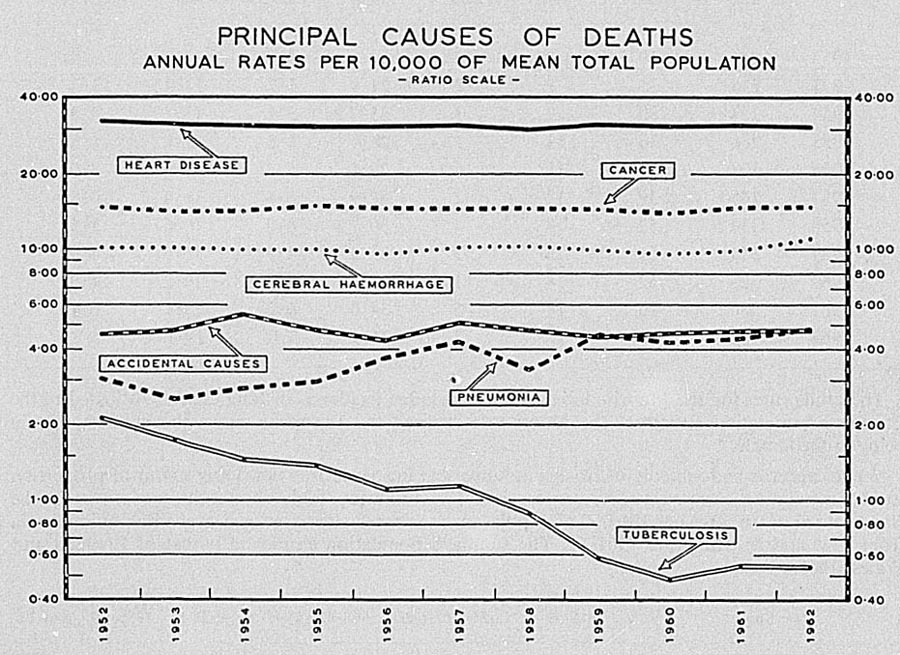

Principal Causes of Deaths 114

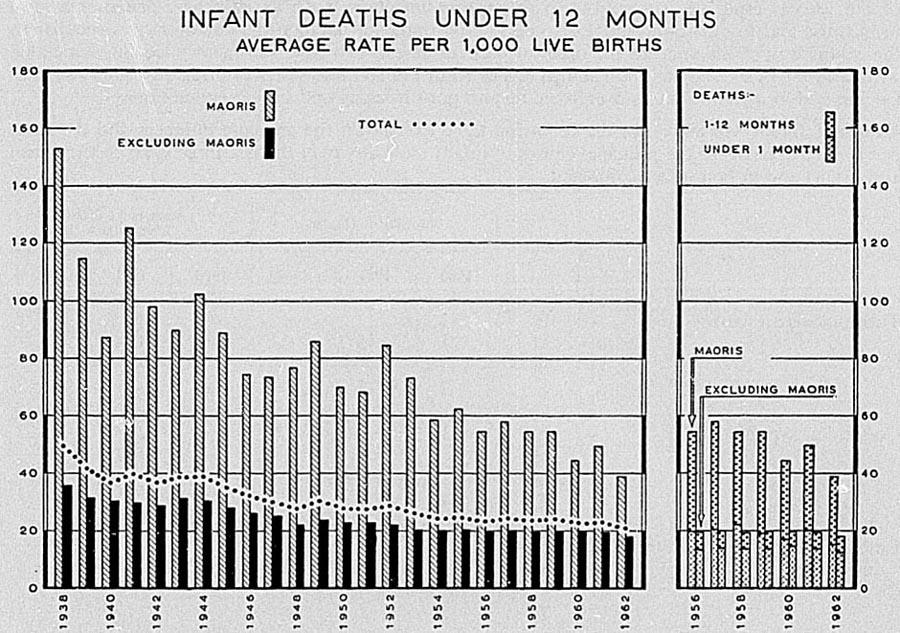

Infant Death Rate 119

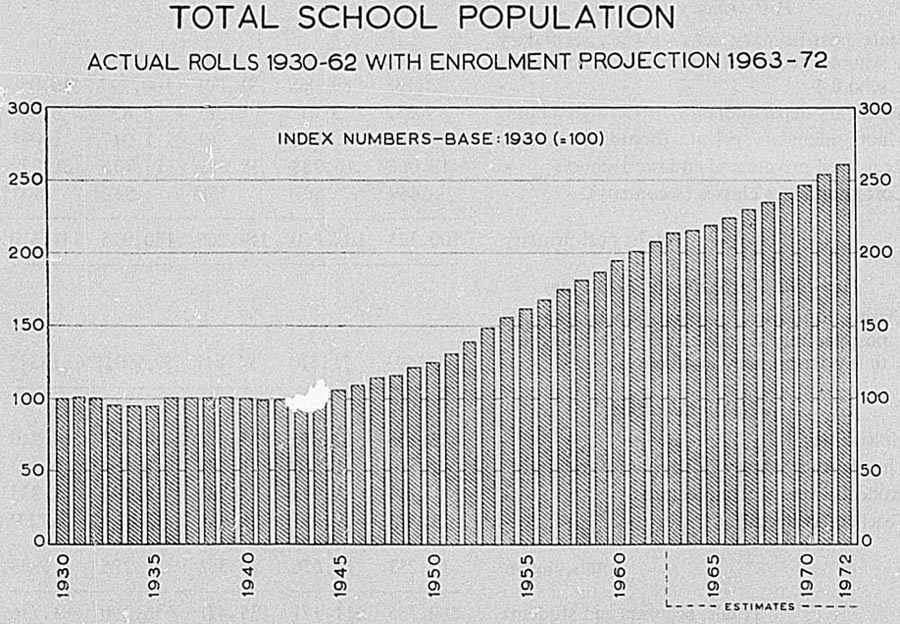

Total School Population 220

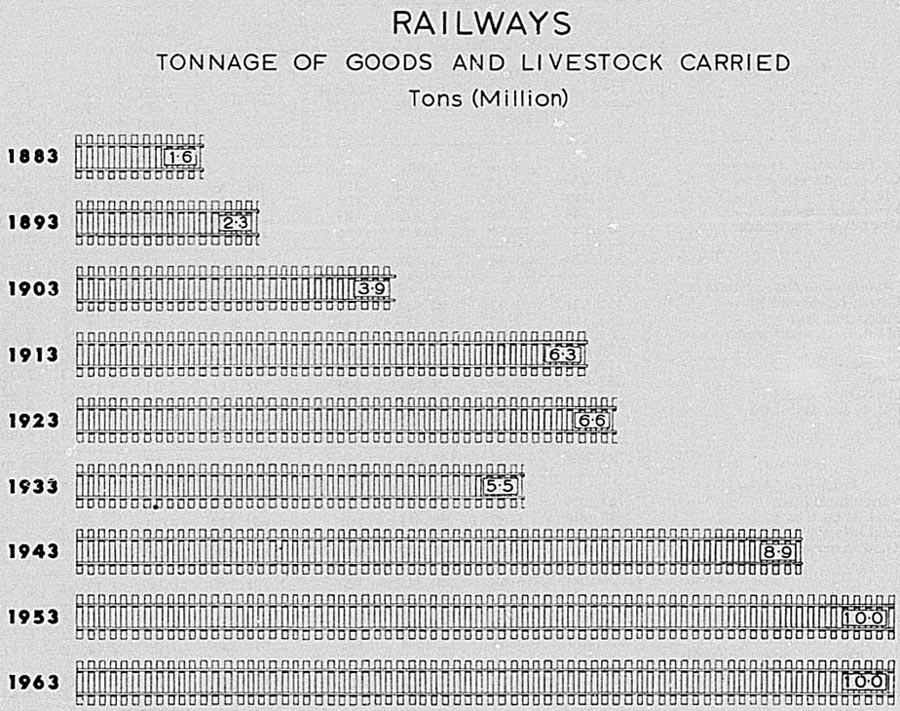

Railways 336

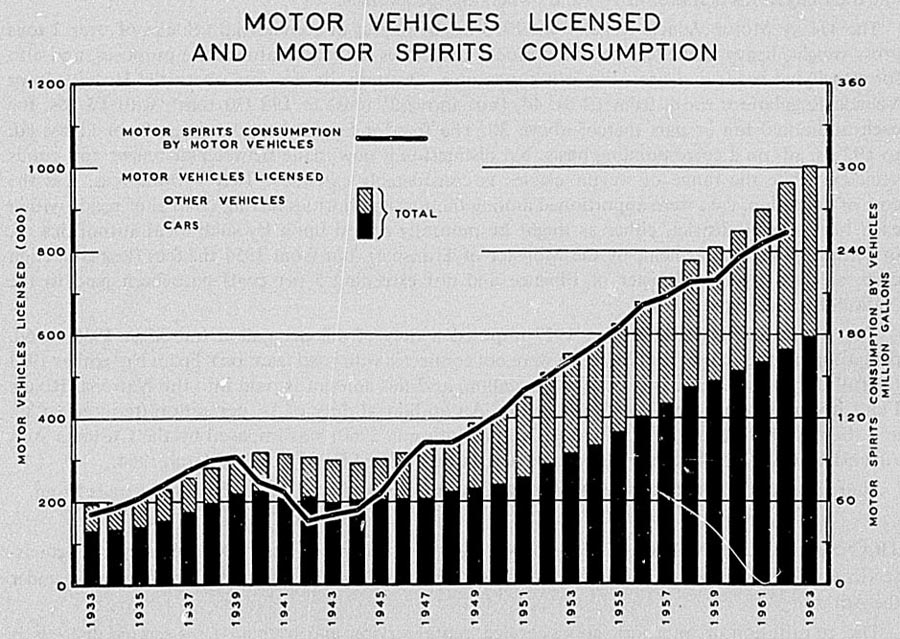

Motor Vehicles Licensed and Motor Spirits Consumption 345

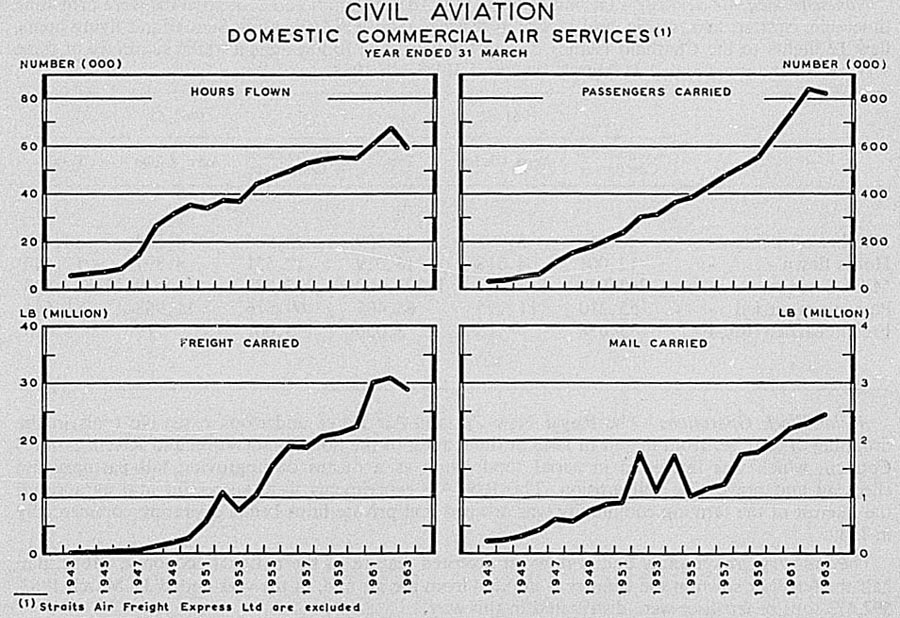

Civil Aviation 361

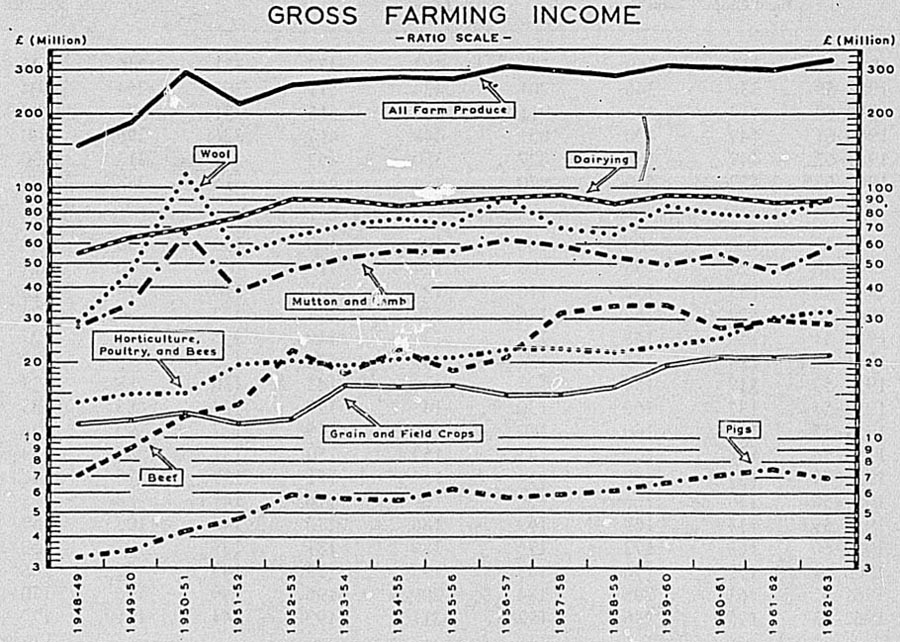

Gross Farming Income 407

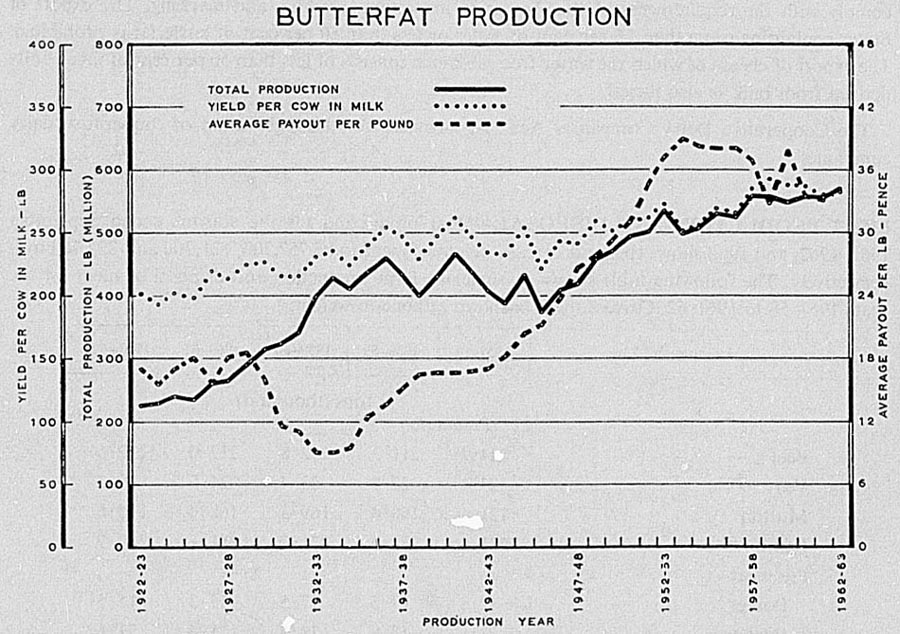

Butterfat Production 411

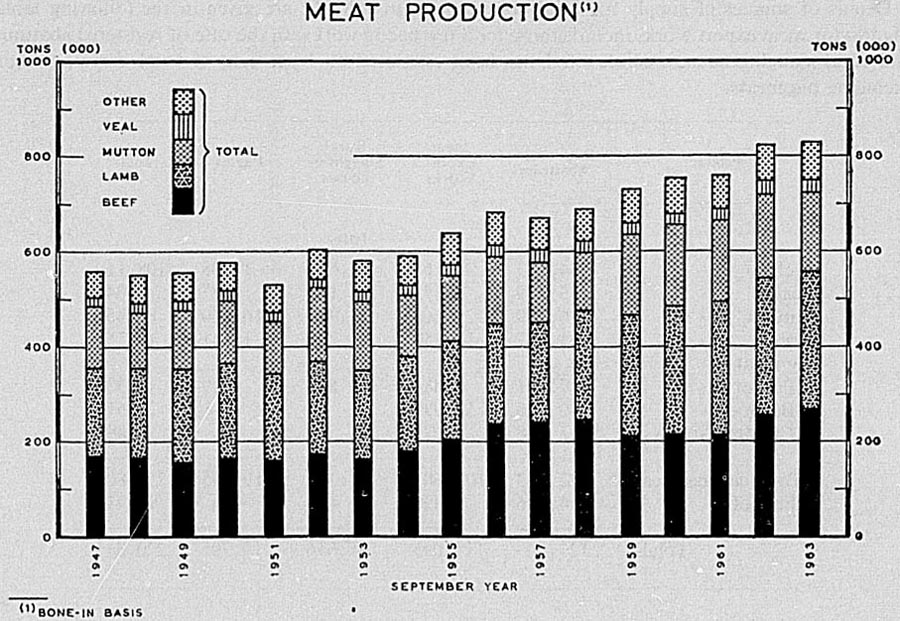

Meat Production 413

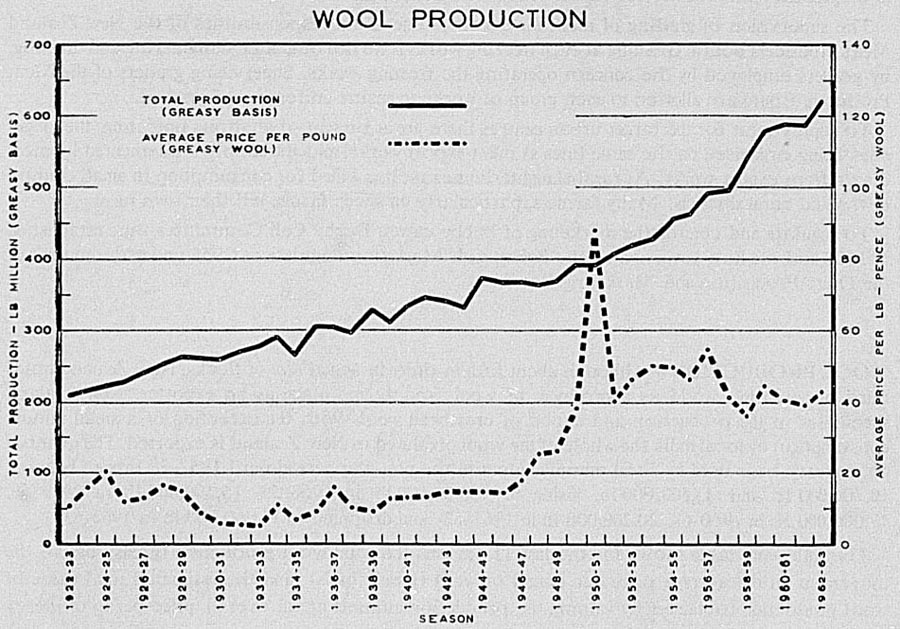

Wool Production 416

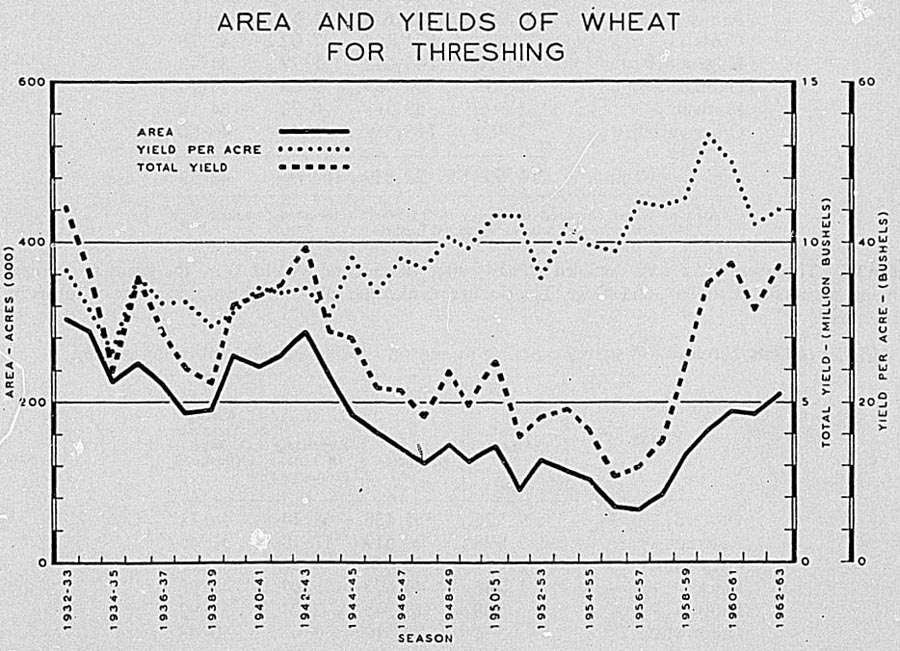

Area and Yields of Wheat for Threshing 431

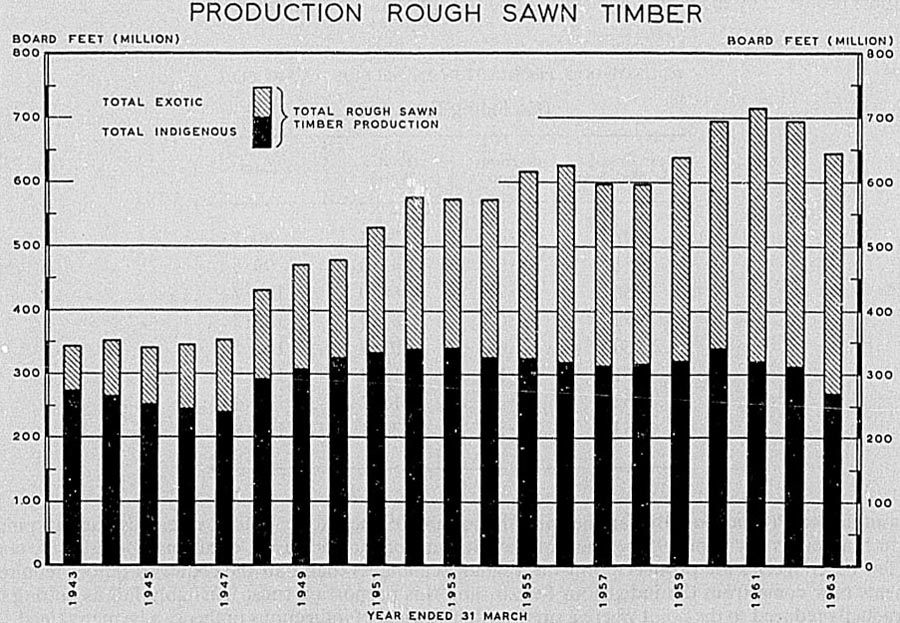

Production Rough Sawn Timber 468

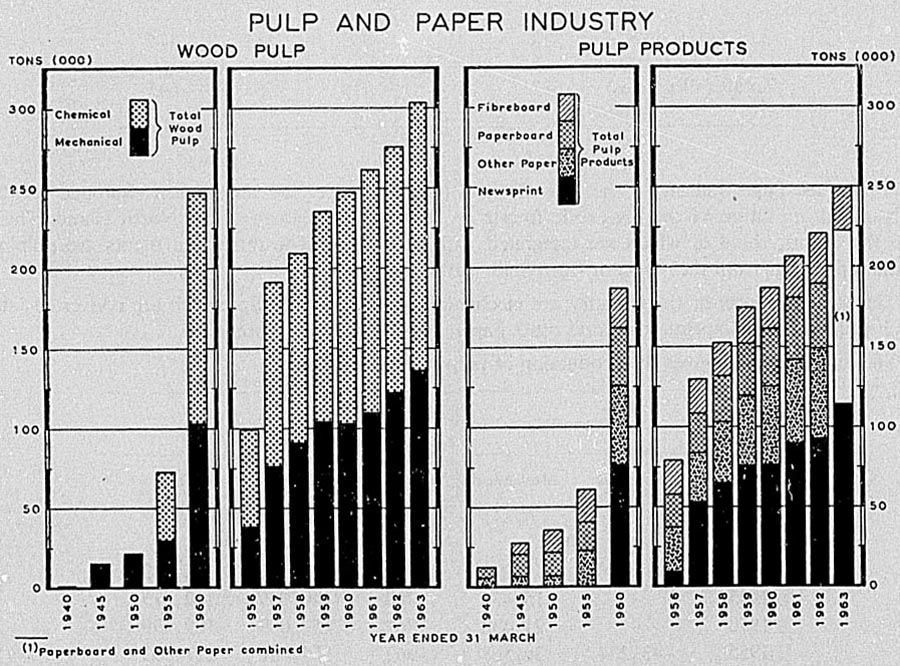

Pulp and Paper Industry 470

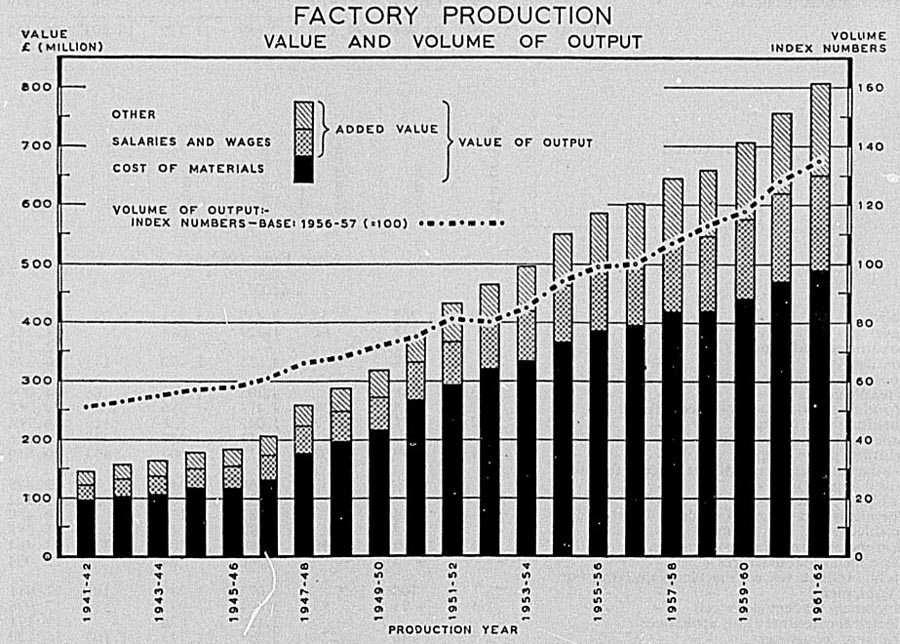

Factory Production 524

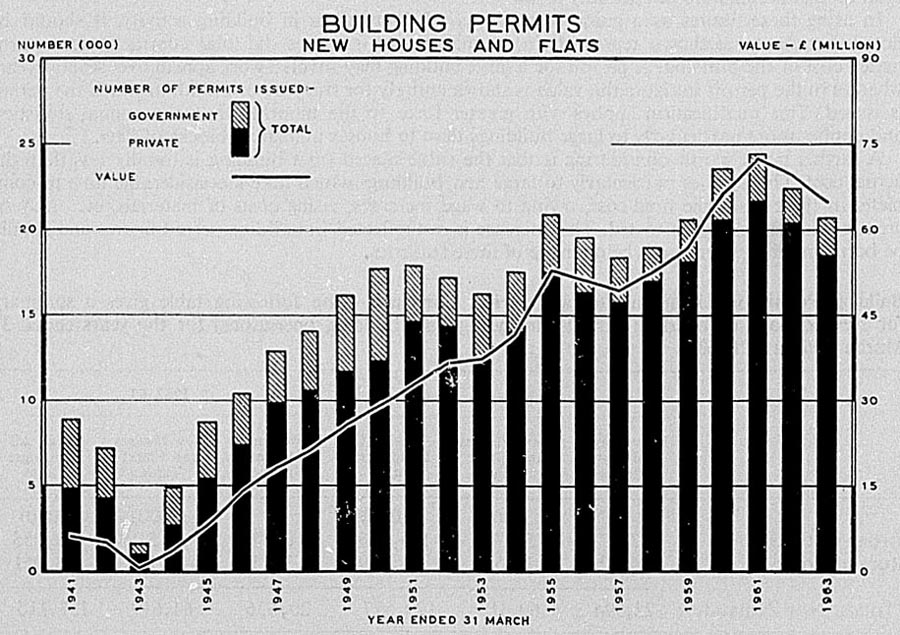

Building Permits 562

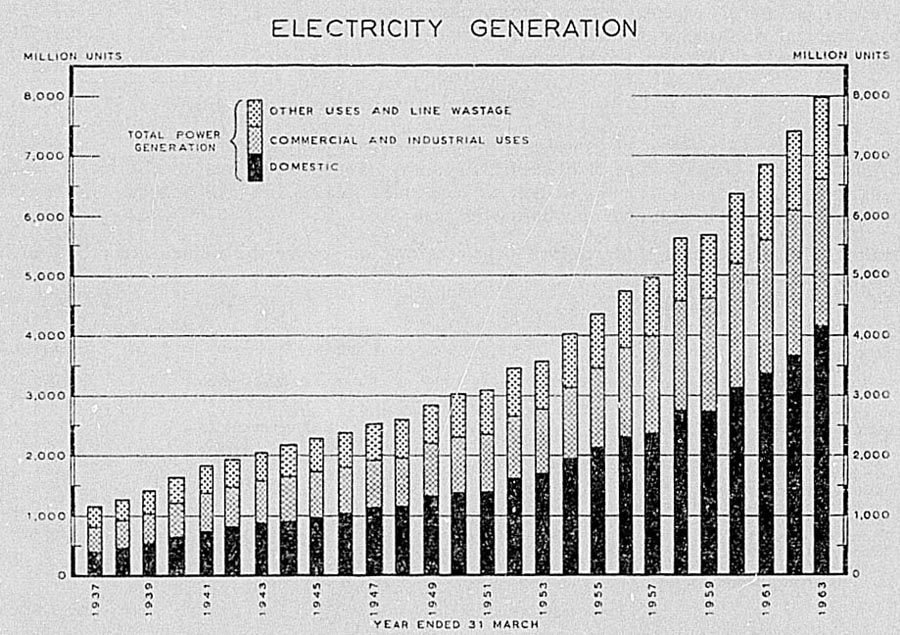

Electricity Generation 580

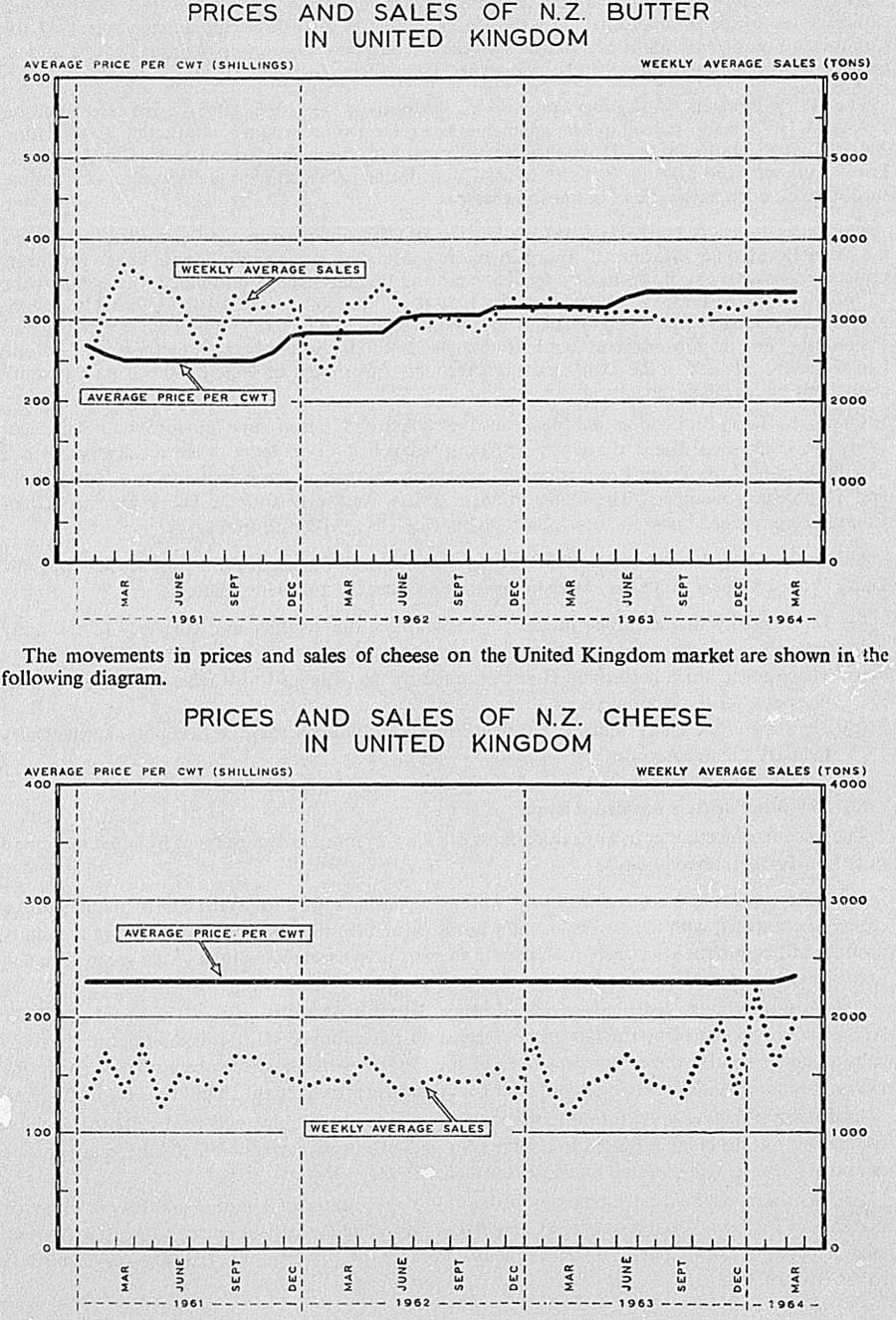

Prices and Sales of Butter in United Kingdom 599

Prices and Sales of Cheese in United Kingdom 599

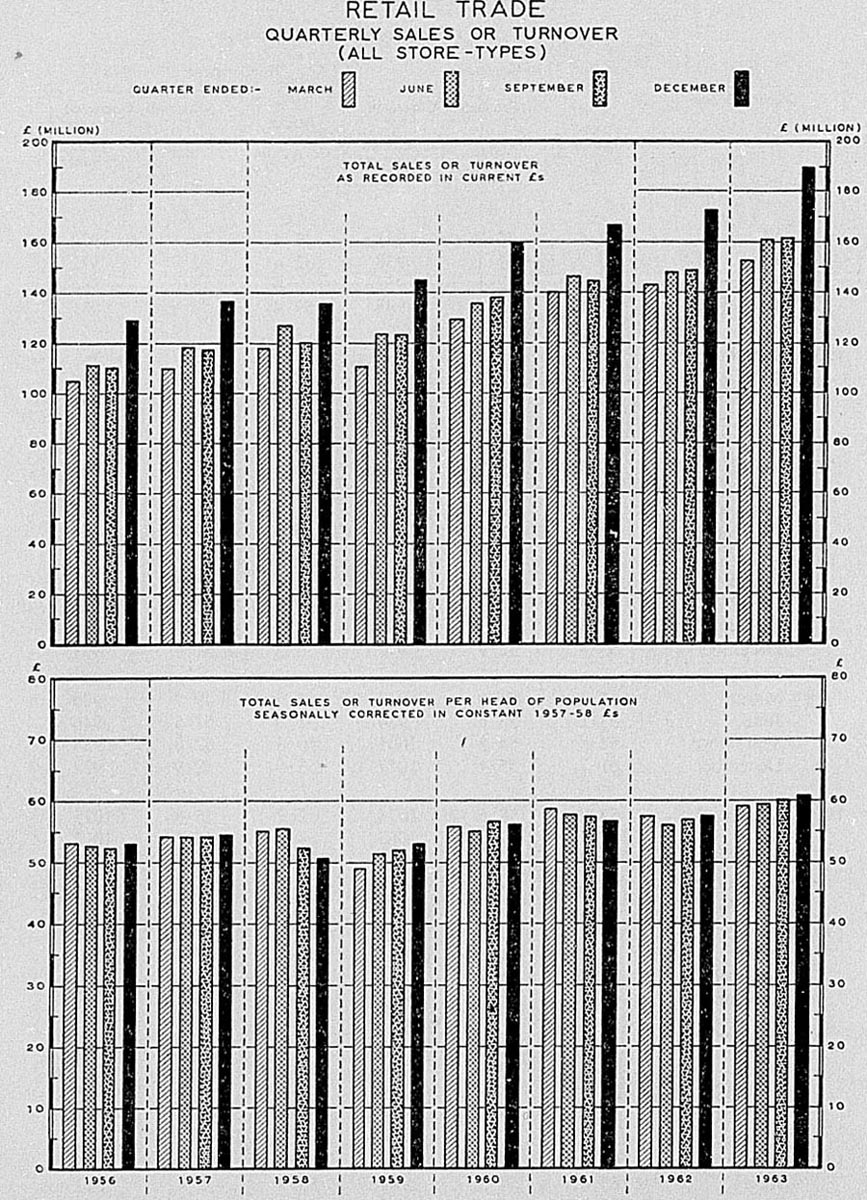

Retail Trade 624

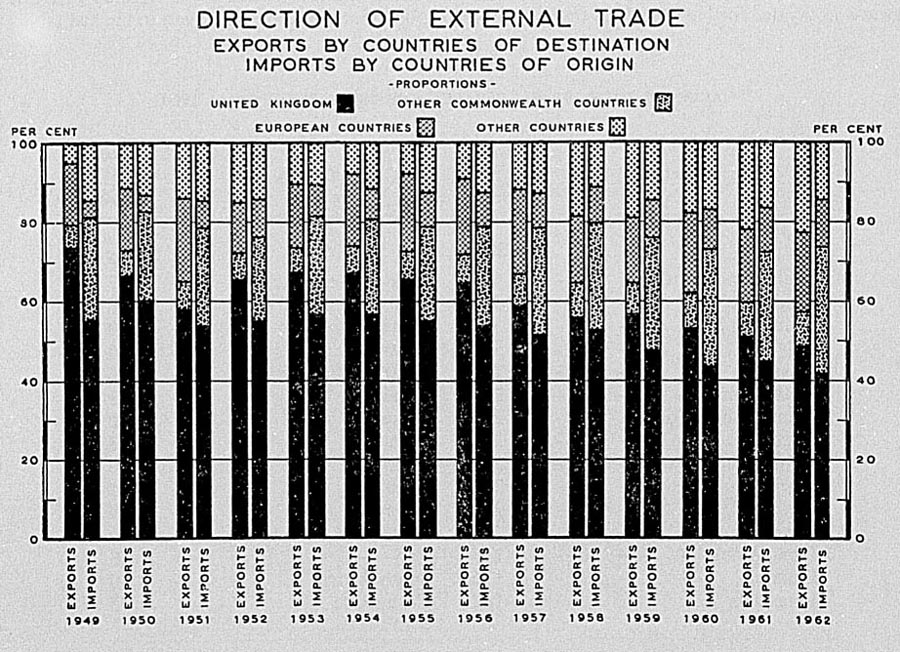

Direction of External Trade 631

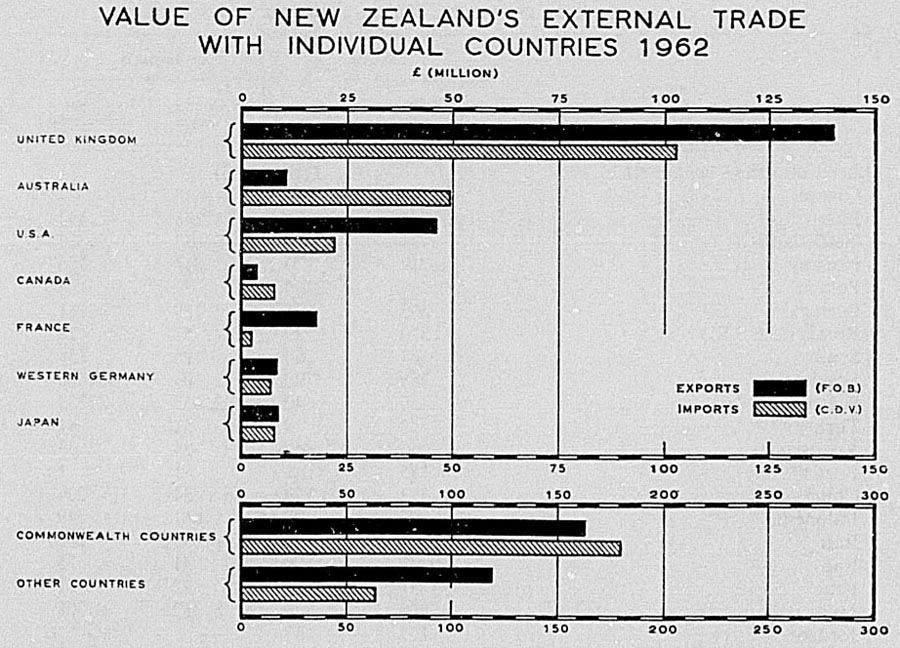

Value of External Trade with Individual Countries 638

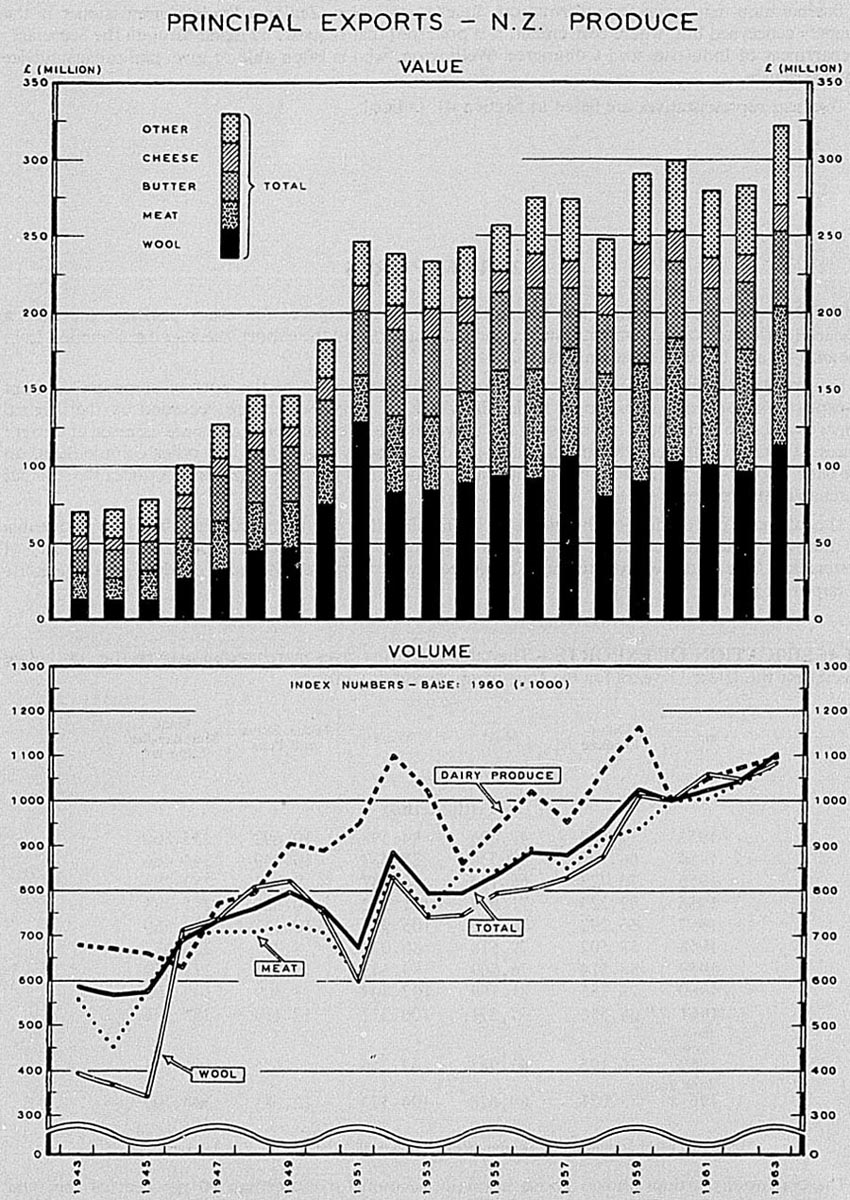

Principal Exports – New Zealand Produce 648

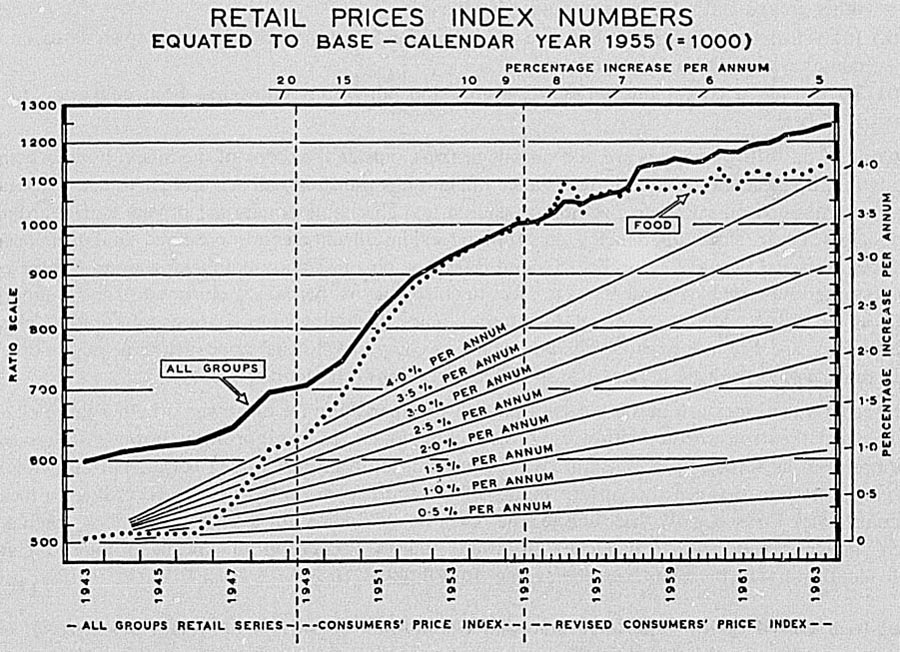

Retail Prices Index Numbers 714

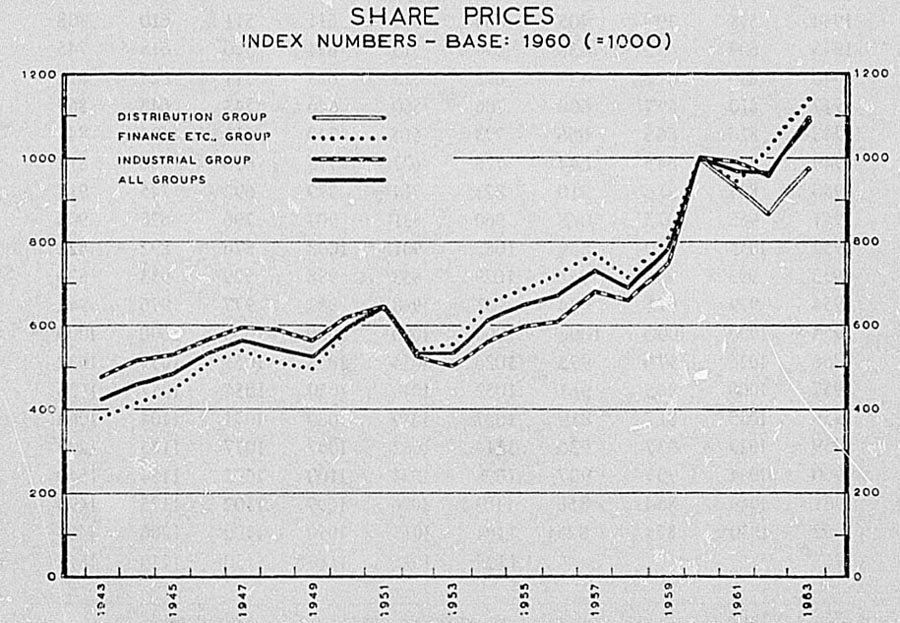

Share Prices 731

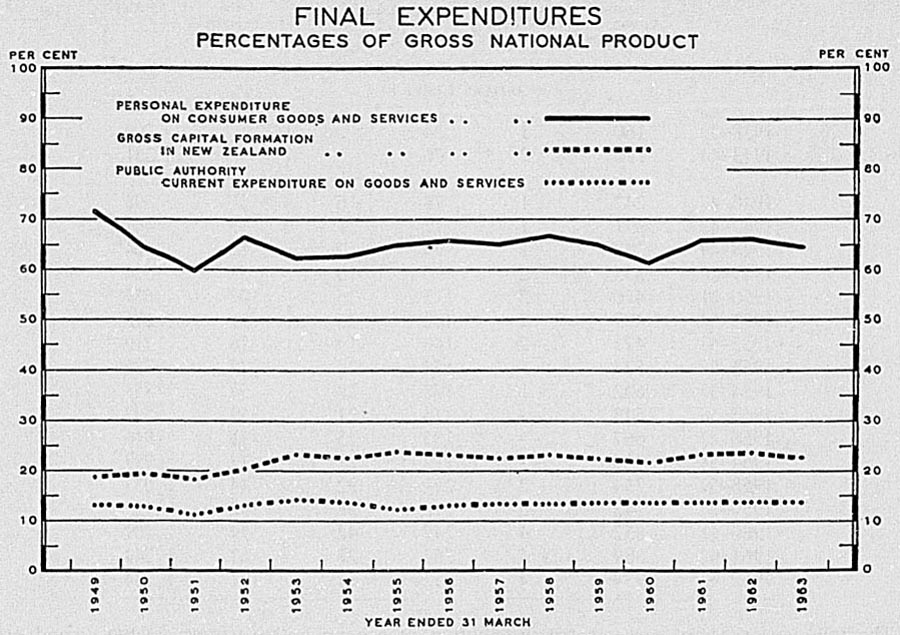

Final Expenditures 745

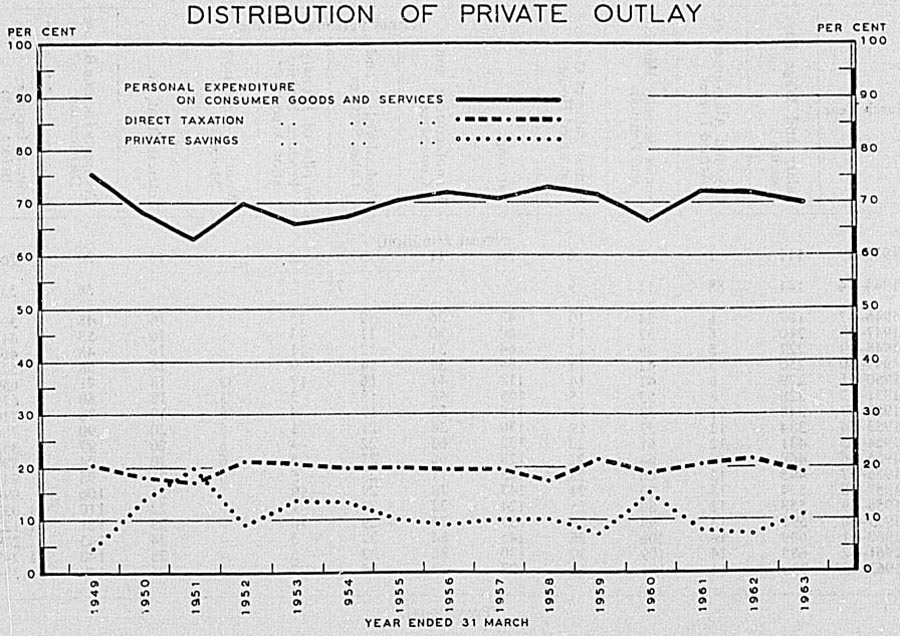

Distribution of Private Outlay 746

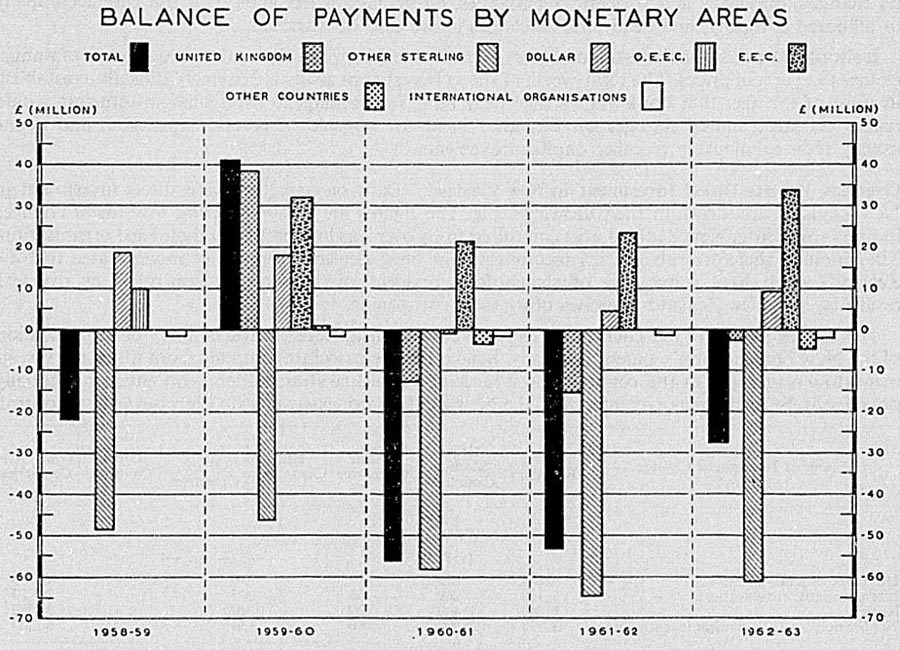

Balance of Payments by Monetary Areas 775

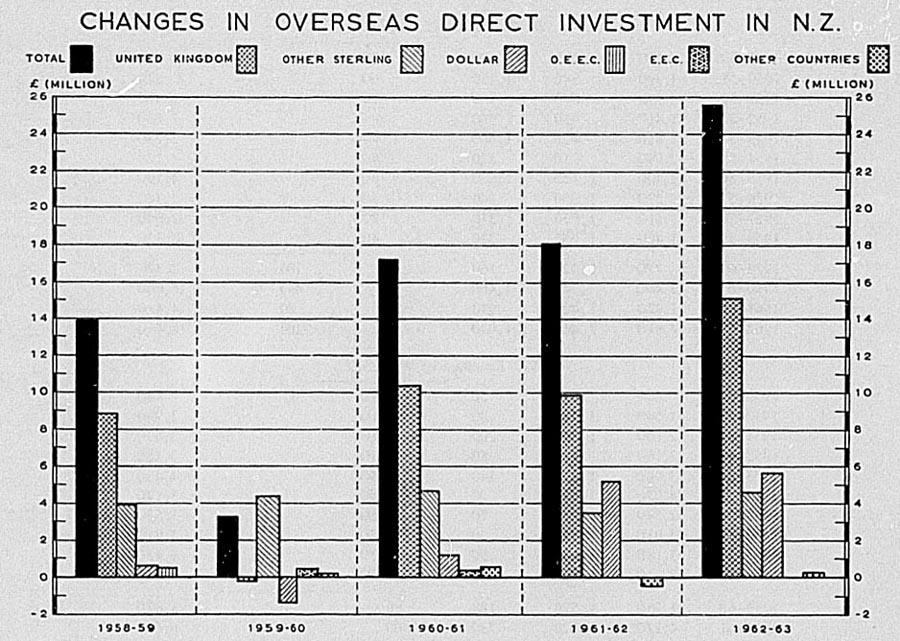

Changes in Overseas Direct Investment in New Zealand 777

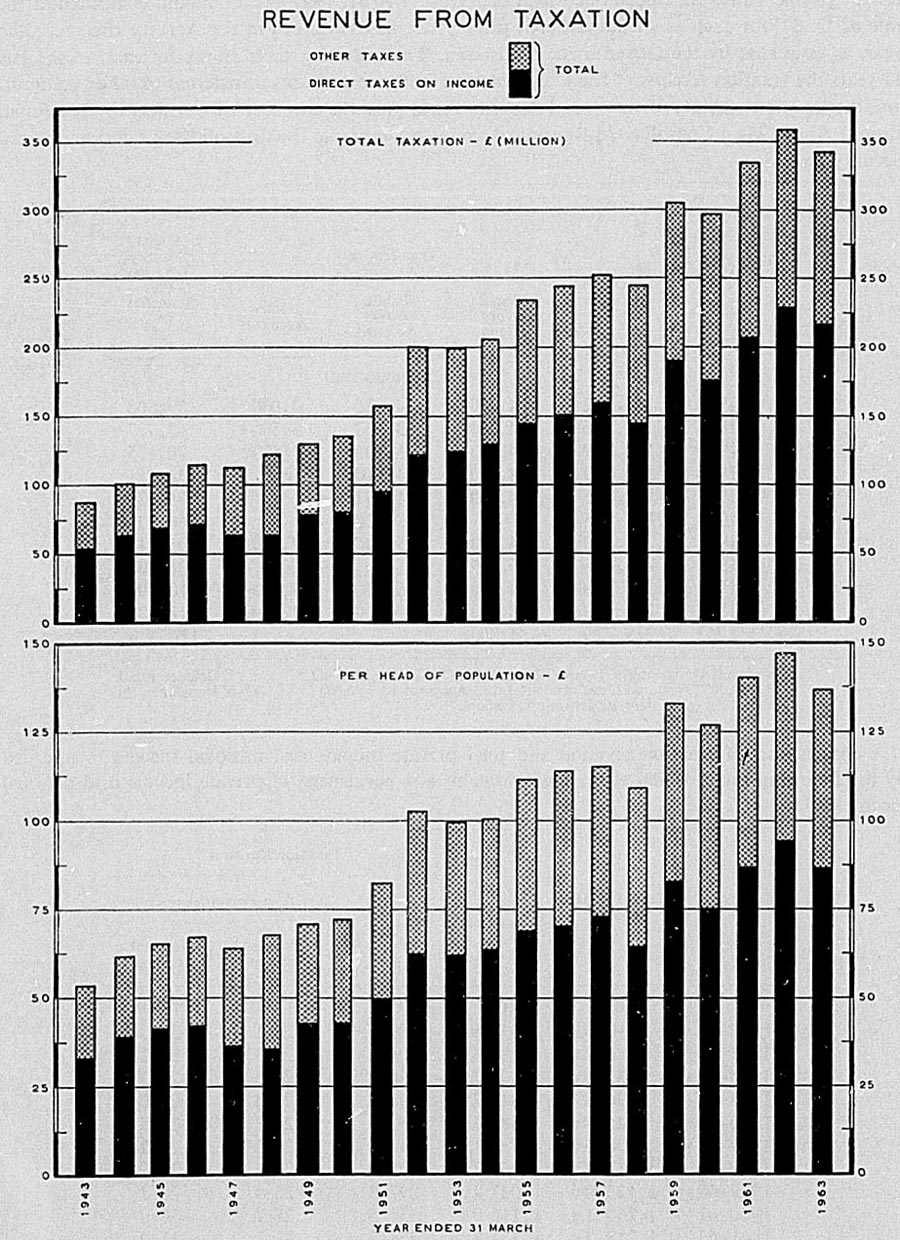

Revenue from Taxation 796

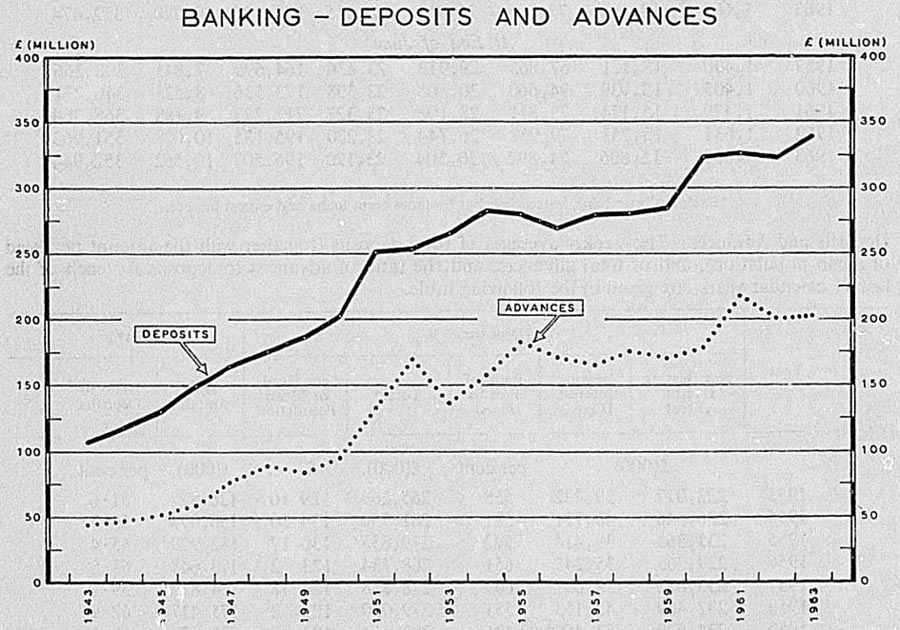

Banking – Deposits and Advances 872

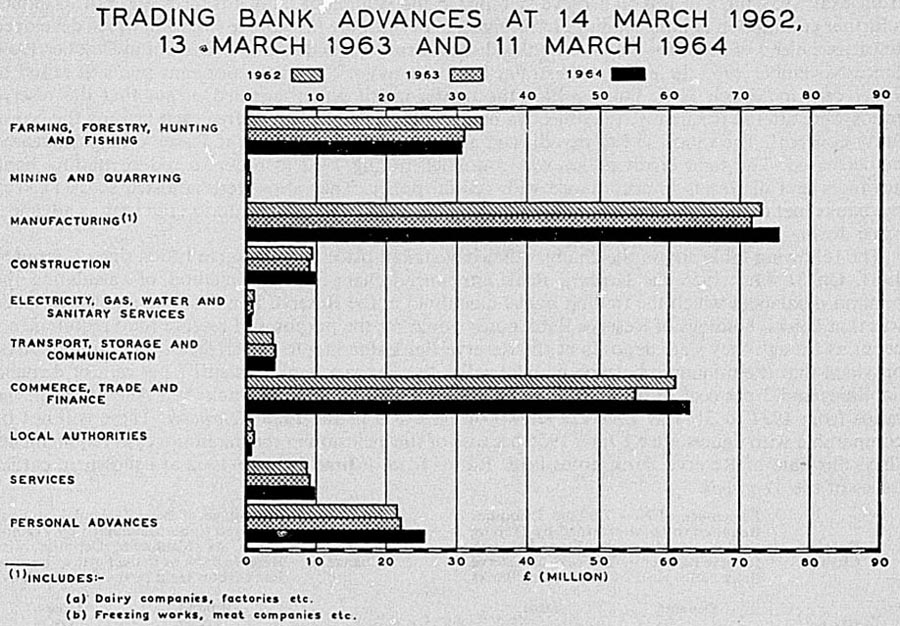

Trading Bank Advances 875

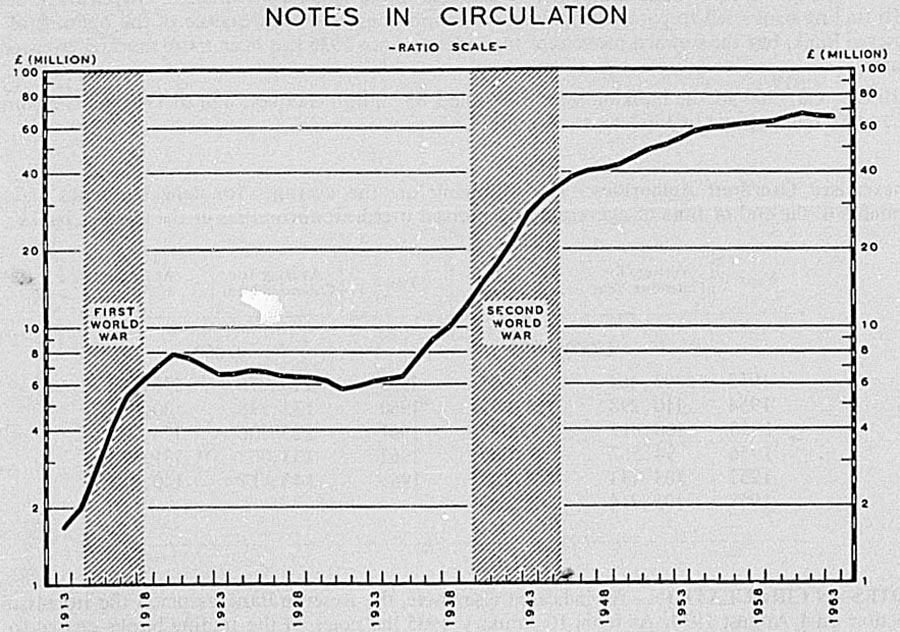

Notes in Circulation 878

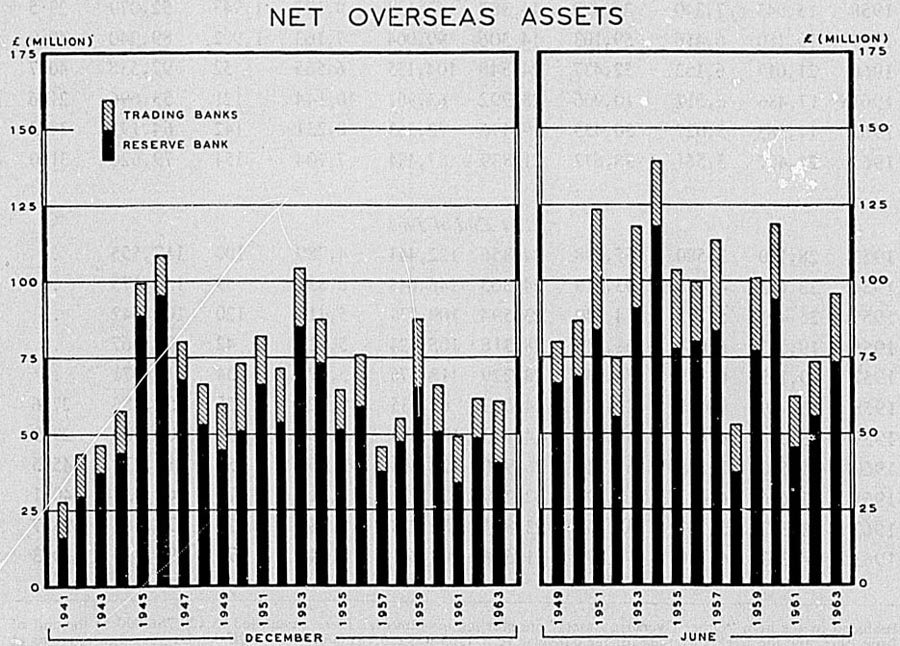

Net Overseas Assets 880

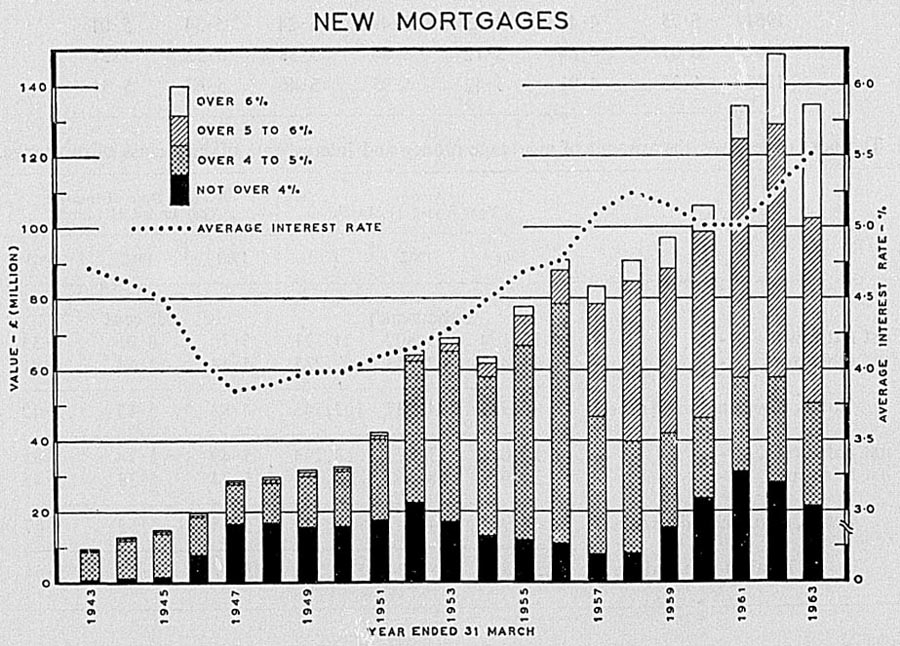

New Mortgages 912

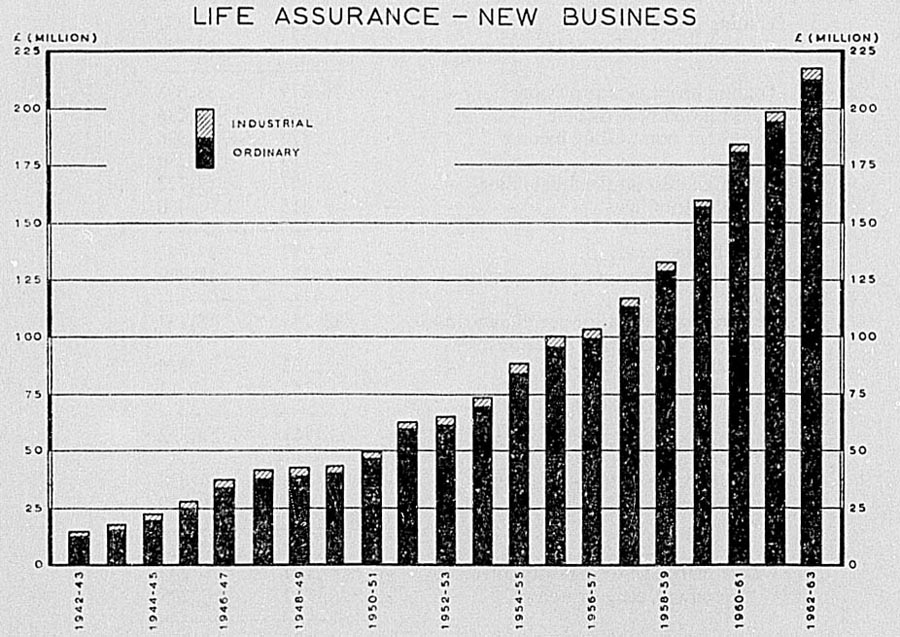

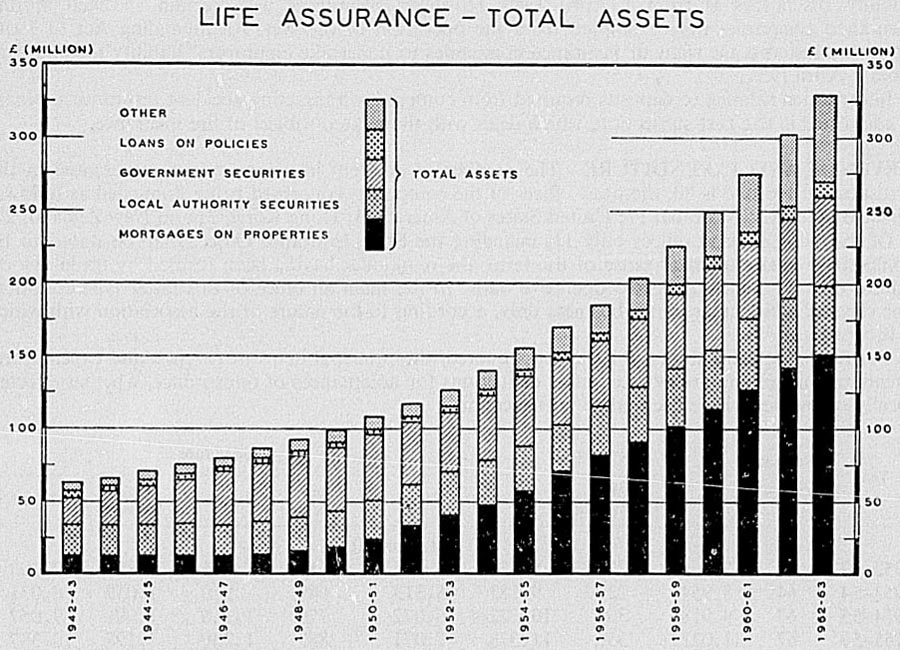

Life Assurance – New Business 930

Life Assurance – Total Assets 937

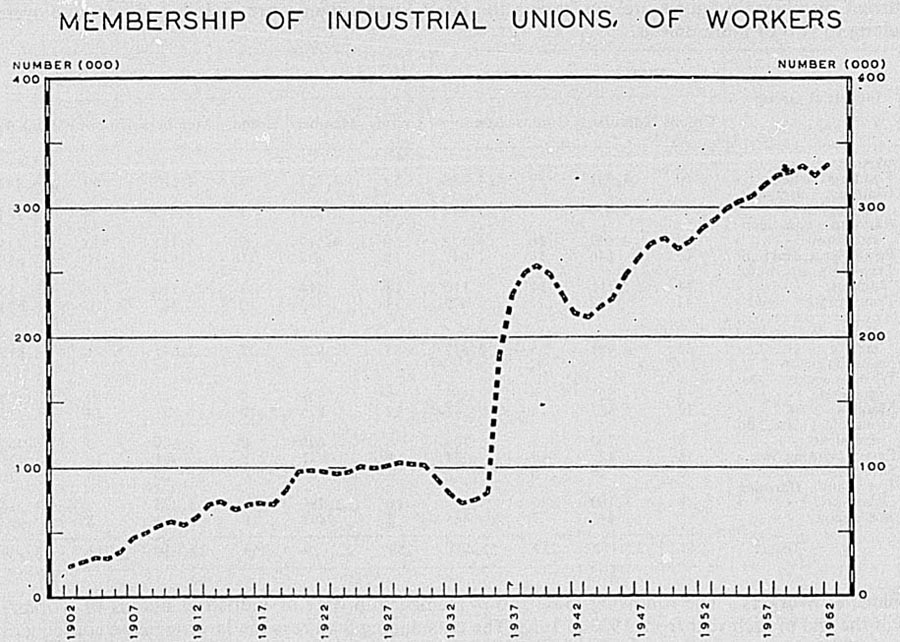

Membership of Industrial Unions of Workers 1006

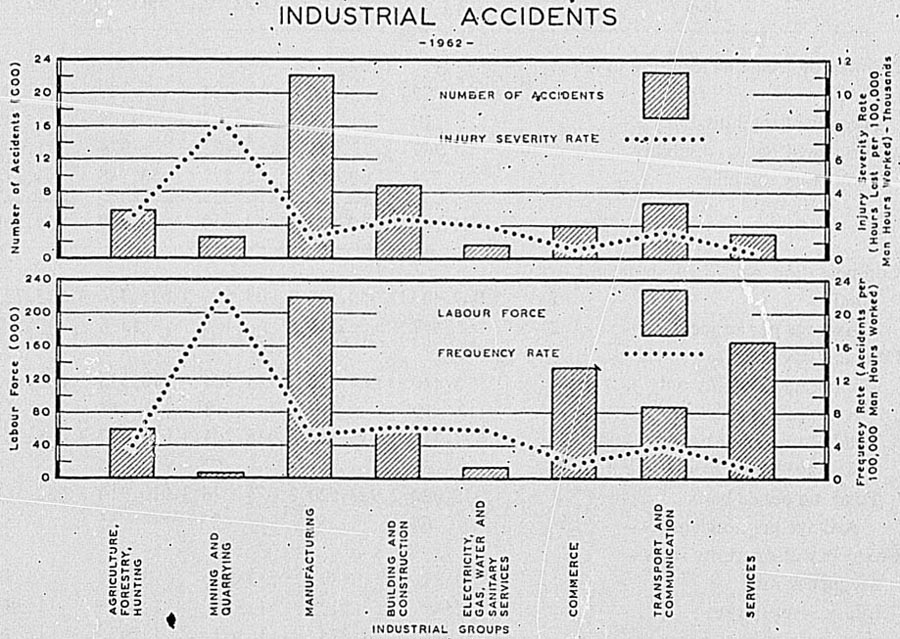

Industrial Accidents 1028

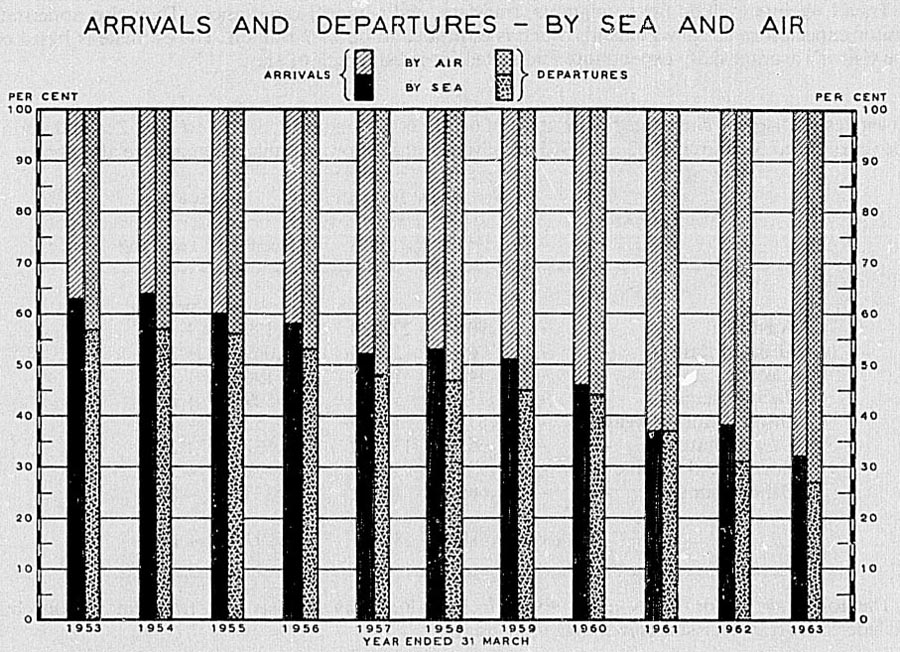

Arrivals and Departures by Sea and Air 1060

Table of Contents

The interpretation of the symbols used in the tables throughout this publication is as follows:

- nil or zero

.. figures not available

not yet available = space left blank

… not applicable

- - amount too small to be expressed

x revised

On occasions figures are rounded off to the nearest thousand or some other convenient unit. This may result in a total disagreeing slightly with the total of the individual items as shown in tables. Where figures are rounded the unit is in general expressed in words below the table headings, but where space does not allow this the unit may be shown as 000 for thousand, etc.

Figures for fiscal years ended 31 March (the fiscal year) are indicated in the text and headings of tables; otherwise figures are mainly for calendar years.

| bd. ft. | board feet |

| ch | chains |

| ctd. | continued |

| cu. ft. | cubic feet |

| cwt | hundredweight |

| d. | pence |

| E | east |

| ft | feet |

| g | gramme |

| gal | gallon |

| h | hour |

| h.p. | horsepower |

| in. | inch |

| kW | kilowatt |

| kWh | kilowatt-hour |

| lb | pound |

| m | mile |

| min | minute |

| mm | millimetre |

| N | north |

| n.e.i. | not elsewhere included |

| n.e.c. | not elsewhere classified |

| oz | ounce |

| £(000) | thousand pounds |

| £(m) | million pounds |

| s. | shillings |

| S | south |

| sq. ft. | square feet |

| sup. ft. | super feet |

| W | west |

| y | yard |

Table of Contents

GEOGRAPHICAL POSITION – The islands of New Zealand have been shaped from the projecting crests of earth folds which rise as broad ridges from the floor of the South Pacific Ocean, 1,000 miles east of the continent of Australia. There are three main islands – North, South, and Stewart separated only by relatively narrow straits – with adjacent islets and a small group called Chatham Islands, 530 statute miles to the east of Lyttelton Dating from 1842 the administrative boundaries of New Zealand, exclusive of island territories, extend from 33 degrees to 53 degrees south latitude and from 162 degrees east longitude to 173 degrees west longitude. Inhabited outlying minor islands are Raoul Island in the Kermadec Group, 620 statute miles north-east of the Bay of Islands, and Campbell Island, 370 statute miles south of Stewart Island.

New Zealand is also responsible for the administration of three island groups in the south-west Pacific – the Cook Islands, Niue Island, and the Tokelau Islands. These are incorporated within the boundaries of New Zealand. The principal island of the Cook Group, Rarotonga, is 1,870 statute miles north-east of Auckland, and Niue to the west of the Cook Islands is 1,550 statute miles from Auckland. Lying to the north-west of the Cook Islands are the Tokelau Islands. In all, there are 23 islands scattered over a vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean making up New Zealand's island territories. The territorial area reaches to within 8 degrees of the Equator and extends south to the Tropic of Capricorn, while in longitude it covers nearly 20 degrees (156 degrees west to 173 degrees west).

The Ross Dependency, some 1,500 statute miles to the south, has been under New Zealand's jurisdiction since 1923 and comprises the sector of the Antarctic continent between 160 degrees east and 150 degrees west longitude, together with the islands lying between those degrees of longitude and south of latitude 60 degrees south.

The administrative area of New Zealand can be classified as follows. In this Yearbook, in general, New Zealand refers to the group of islands shown in (a) only, unless it is expressly stated that the other islands as a whole or in part are included.

New Zealand:

*Situated off North Island. †Situated off South Island. | |

|---|---|

| (a) Exclusive of island territories– | Area in Square Miles |

| North Island | 44,281 |

| South Island | 58,093 |

| Stewart Island | 670 |

| Chatham Islands | 372 |

| Minor islands– | |

| Inhabited– | |

| Kermadec Islands* | 13 |

| Campbell Island† | 44 |

| Uninhabited (areas in parentheses) | 263 |

| Three Kings* (3); Snares† (1); Solander† (1/2); Antipodes† (24); Bounty† (1/2); Auckland† (234). | |

| Total New Zealand, exclusive of island territories | 103,736 |

| (b) Island territories– | |

| Tokelau Islands, comprised of – | Area in Square Miles |

| Fakaofo Island, Nukunono Island, Atafu Island | 4 |

| Cook and associated islands, comprised of – | |

| Southern Group | 82 |

| Rarotonga, Aitutaki, Mangaia, Mauke, Atiu, Takutea, Mitiaro, Manuae and Te-au-o-tu. | |

| Northern Group | 11 |

| Palmerston, Pukapuka, Penrhyn, Suwarrow, Manihiki, Nassau, Rakahanga. | |

| Niue Island | 100 |

| Total island territories | 197 |

| (c) Ross Dependency (Estimated) | 160,000 |

| Total New Zealand, inclusive of island territories and Ross Dependency | 263,933 |

The total area of the foregoing groups, exclusive of the Ross Dependency, is 103,933 square miles. Elsewhere in this volume – viz, in the section on land tenure, settlement, etc. – the aggregate area of New Zealand appears as 66,390,700 acres – i.e., 103,736 square miles. The latter area does not include the Cook and associated islands or the Tokelau Islands. (Western Samoa, which had been administered as a trust territory since 1946, became an independent territory from 1 January 1962.)

The relevant Proclamations, defining from time to time the administrative area of New Zealand, are briefly referred to in Section 2.

GEOGRAPHICAL FEATURES: Coastline–Since the combined length of the North and South Islands extends just over a thousand miles, and since the width of neither Island exceeds 280 miles at its broadest point, New Zealand possesses a very lengthy coastline in proportion to its area. With the exception of the low-lying North Auckland Peninsula, the New Zealand land mass lies along a south-westerly and north-easterly axis, parallel to the direction of its mountain chains.

By reason of the latter fact the coastline is, on the whole, not greatly indented; and, as a consequence, New Zealand is not well endowed with natural harbours. In the North Island, Auckland and Wellington are two safe natural harbours of which the fullest commercial use is made and the use of Tauranga harbour is expanding. On the east coast of the North Auckland Peninsula several deep and sheltered harbours exist, but production from the hinterland is limited. In the South Island the Marlborough Sounds and the West Coast Sounds form perfect land-locked harbours, but owing to their situations and to the rugged nature of the terrain they have – with the exception of Queen Charlotte Sound – little or no commercial utility. Where vital localities have not been endowed with ideal harbours it has been necessary to improve existing facilities by dredging and by breakwater construction, etc. In this manner efficient ports, capable of accommodating overseas vessels, have been formed in Lyttelton, Otago, and Bluff Harbours. On the west coast of both Islands the strong ocean drifts and high seas cause shoaling at river mouths and harbour entrances, while on the east coast of the South Island similar circumstances prevail, due to the large quantities of shingle brought down by the rivers being spread along the coast by ocean currents. The mountainous nature of the country makes the haulage of goods to and from the better equipped natural harbours both costly and difficult, and the construction and maintenance of further ports at various points along the coasts of both Islands has been necessary, either by dredging river mouths or by harbour-construction work.

Mountains – The mountainous nature of New Zealand is one of its most striking physical characteristics, less than one-quarter of the land surface lying below the 650 ft contour. In the North Island the higher mountains occupy approximately one-tenth of the surface; but, with the exception of the four volcanic peaks of Egmont (8,260 ft), Ruapehu (9,175 ft), Ngauruhoe (7,515 ft), and Tongariro (6,458 ft), they do not exceed an altitude of 6,000 ft. Of these four volcanoes only the first named can be classed as dormant. Ruapehu and Ngauruhoe have been particularly active from time to time. Other volcanoes include Mount Tarawera and White Island, each of which has, upon one occasion within historical times, erupted with disastrous consequences. Closely connected with the volcanic system are the multitudinous hot springs and geysers.

The mountain system of the North Island runs generally in a south-west direction, parallel to the coast, from East Cape to Turakirae Head, and includes the following ranges from the north: Raukumara, Huiarau, Ruahine, Tararua, and Rimutaka. This chain is flanked on the west between the Huiarau and Ruahine by the Ahimanawa, Kaweka, and Kaimanawa Ranges, while west of the Kaimanawa is the National Park volcanic group comprising Mounts Ruapehu, Ngauruhoe, and Tongariro. The Hauhangaroa and Rangitoto Ranges run in a northerly direction from the National Park group. In the east the Moehau Range parallels the length of the Coromandel Peninsula. Mount Egmont forms the only area above 4,000 ft on the west coast of this Island.

The South Island is much more mountainous than the North, but shows fewer manifestations of recent volcanic activity. Along almost the entire length of the Island runs the massive chain known as the Southern Alps, which attains its greatest height in Mount Cook (12,349 ft), while no fewer than 15 peaks exceed 10,000 ft. West and north-west of the main portion of the Southern Alps are the Victoria, Brunner, and Lyell Ranges and the Tasman Mountains, the Victoria Range being flanked by the Paparoa Range. To the north run the St. Arnaud and Richmond Ranges, while to the north-east are the Spenser Mountains and the Kaikoura and Seaward Kaikoura Ranges, the two latter ranges running parallel to the east coast. The south portion of the Southern Alps breaks up into a miscellany of ranges dominating the mountainous Fiord and north-western Southland regions.

As might be expected, the higher mountains of the South Island have exerted a greater influence on the economic development of the country than those of the North Island. For many years the Southern Alps were an effective barrier to communication by land between the east and west coasts, while their climatic effects on the Canterbury plains and Otago plateaus determined the types of cultivation undertaken. Moreover, the existence of much elevated open country led to the development of pastoral holdings on a large scale. While the mountains in the North Island are not as high nor as extensive as those of the South Island, in the early days they effectively isolated various portions of the coastal plains and valleys. Their effect on climatic conditions, however, is considerably less, the rainfall being more evenly distributed. Owing to this more even distribution of the rainfall, and to the existence of considerable areas of lower relief, the foothills of the mountain systems were heavily wooded, and so proved a hindrance to agrarian development.

There are at least 223 named peaks of 7,500 ft or more in altitude. Below is a list of the peaks restricted to the four largest volcanic cones in the North Island and to mountains of a minimum height of 9,000 ft in the South Island.

| Mountain or Peak | Height (Feet) |

|---|---|

| NORTH ISLAND | |

| Ruapehu | 9,175 |

| Egmont | 8,260 |

| Ngauruhoe | 7,515 |

| Tongariro | 6,458 |

| SOUTH ISLAND | |

| Kaikoura Ranges – | |

| Tapuaenuku | 9,465 |

| Alarm | 9,400 |

| Southern Alps – | |

| Cook | 12,349 |

| Tasman | 11,475 |

| Dampier | 11,287 |

| Silberhorn | 10,757 |

| Lendenfeldt | 10,450 |

| David's Dome | 10,443 |

| Malte Brun | 10,421 |

| Torres | 10,376 |

| Teichelmann | 10,370 |

| Sefton | 10,359 |

| Haast | 10,294 |

| Elie de Beaumont | 10,200 |

| Douglas Peak | 10,107 |

| La Perouse | 10,101 |

| Haidinger | 10,059 |

| Aspiring | 9,957 |

| Hamilton | 9,915 |

| Glacier Peak | 9,865 |

| De la Beche | 9,815 |

| Aiguilles Rouges | 9,731 |

| Nazomi | 9,716 |

| Darwin | 9,715 |

| Chudleigh | 9,686 |

| Annan | 9,667 |

| Low | 9,653 |

| Haeckel | 9,649 |

| Le Receveur | 9,562 |

| Goldsmith | 9,532 |

| Big Mac | 9,511 |

| Conway Peak | 9,510 |

| Bristol Top | 9,508 |

| Walter | 9,507 |

| Grey | 9,490 |

| Green | 9,307 |

| Hutton | 9,297 |

| D'Archiac | 9,279 |

| Ronald Adair | 9,276 |

| Hochstetter Dome | 9,258 |

| Earnslaw | 9,250 |

| Nathan | 9,200 |

| Barnicoat | 9,183 |

| Sibbald | 9,181 |

| Arrowsmith | 9,171 |

| Spencer | 9,167 |

| The Footstool | 9,073 |

| Rudolf | 9,039 |

| The Dwarf | 9,025 |

| Darran Range – | |

| Tutoko | 9,042 |

Glaciers – In keeping with the dimensions of the mountain system, New Zealand possesses, in the South Island, a glacial system of some magnitude. Of the glaciers the largest is the Tasman, which, with others of comparable size, rises in the more elevated area surrounding Mount Cook. Flowing down the eastern slope of the range, the Tasman Glacier has a length of 18 miles and a width of 1 1/4 miles. In common with other glaciers on the eastern slope, of which the more important are the Murchison (11 miles), the Mueller (8 miles), the Godley (8 miles), and the Hooker (7 1/4 miles), its rate of flow is slow, while its terminal face is at an altitude of somewhat over 2,000 ft. On the western slope of the range, owing to the greater snow precipitation, the glaciers are more numerous and descend to lower levels, while the steeper slope gives them a more rapid rate of flow. The two largest of these are the Fox and the Franz Josef, with lengths of 9 3/4 miles and 8 1/2 miles respectively, and terminal faces at altitudes of 670 ft and 690 ft.

As will be realised, these glaciers are an important tourist attraction, and as such have definite economic significance. Moreover, those glaciers on the eastern slopes which feed rivers utilised for irrigation and hydro-electric purposes are valuable in that they help to ensure a steady volume of water throughout the year.

Rivers – Of the numerous New Zealand rivers few are of sufficient length or volume to be navigable. Moreover, owing to the high relief of the country, they are mostly swift-flowing, while, as mentioned previously, nearly all are obstructed at their mouths by bars. For the purpose of internal communication, therefore, they are of little economic utility, and only in two or three isolated instances have they been thus consistently used. With improved roading conditions, however, their traffic has become negligible even in these cases.

As sources of hydro-electric power New Zealand rivers are of considerable importance, since their rapid rate of flow and dependable volume of ice-free water make them eminently suitable for this purpose. At the present time the Waikato and the Mangahao in the North Island and the Waitaki, Cobb, Clutha, and Waipori in the South are used for major hydro-electric schemes. The characteristics just mentioned are also important for purposes of irrigation, but, owing to the country's reliable rainfall, there are few areas other than in Canterbury and Otago where the rivers are so utilised.

Following is a list of the more important rivers. For purposes of uniformity, the length of a river is taken to be the distance from the mouth to the farthest point in the system, whether this should happen to bear the same name or that of an affluent, and is inclusive of the estimated course of a river flowing into and emerging from any lake in the system.

NORTH ISLAND

| River | Length (Miles) |

|---|---|

*Cook Strait is defined as follows: northern limit is a line between northern points of Stephens Island and Kapiti Island: southern limit is a line between Cape Palliser and Cape Campbell. | |

| NORTH ISLAND | |

| Flowing into the Pacific Ocean – | |

| Piako | 65 |

| Waihou (or Thames) | 95 |

| Rangitiki | 95 |

| Whakanane | 65 |

| Waiapu (from source, Mata River) | 75 |

| Waipaoa (from source, Waipapa Stream) | 70 |

| Wairoa (from source, Hangaroa River) | 85 |

| Mohaka (from source, Taharua River) | 95 |

| Ngaruroro | 90 |

| Tukituki | 70 |

| Flowing into Cook Strait* – | |

| Ruamahanga | 90 |

| Hutt | 35 |

| Flowing into the Tasman Sea – | |

| Otaki | 30 |

| Manawatu | 120 |

| Rangitikei | 130 |

| Turakina | 70 |

| Wangaehu | 100 |

| Wanganui | 180 |

| Waitotara | 55 |

| Patea | 75 |

| Waitara | 85 |

| Mokau | 85 |

| Waikato (from source, Upper Waikato River) | 270 |

| Wairoa (from source, Waiotu Stream) | 115 |

| Hokianga (from source, Waihou River) | 45 |

SOUTH ISLAND

| River | Length (Miles) |

|---|---|

| SOUTH ISLAND | |

| Flowing into Cook Strait – | |

| Pelorus | 40 |

| Wairau | 105 |

| Awatere | 70 |

| Flowing into the Pacific Ocean – | |

| Clarence | 130 |

| Conway | 30 |

| Waiau-uha (or Waiau) | 105 |

| Hurunui | 90 |

| Waipara | 40 |

| Ashley | 60 |

| Waimakariri | 100 |

| Selwyn | 50 |

| Rakaia | 90 |

| Ashburton | 70 |

| Rangitata (from source, Clyde River) | 75 |

| Opihi | 50 |

| Pareora | 35 |

| Waihao | 45 |

| Waitaki (from source, Hopkins River) | 135 |

| Kakanui | 40 |

| Shag | 45 |

| Taieri | 175 |

| Clutha (from source, Makarora River) | 210 |

| Flowing into Foveaux Strait – | |

| Mataura | 140 |

| Oreti | 120 |

| Aparima (Jacobs River) | 70 |

| Waiau (from source, Clinton River) | 135 |

| Flowing into the Tasman Sea – | |

| Hollyford | 50 |

| Cascade | 40 |

| Arawhata | 45 |

| Haast | 60 |

| Karangarua | 25 |

| Cook | 25 |

| Waiho (from source, Callery River) | 20 |

| Whataroa | 35 |

| Wanganui | 35 |

| Waitaha | 25 |

| Hokitika | 40 |

| Arahura | 35 |

| Taramakau | 50 |

| Grey | 75 |

| Buller (from source, Travers River) | 110 |

| Mokihinui | 35 |

| Karamea | 50 |

| Heaphy | 25 |

| Aorere (from source, Spee River) | 45 |

| Takaka (from source, Cobb River) | 45 |

| Motueka | 70 |

| Waimea (from source, Wai-iti River) | 30 |

The discovery in 1861 that the beds of numerous rivers in the South Island contained extensive deposits of alluvial gold was of considerable importance in the economic development of the country. Not only did it lead to an increase in population and in wealth, but, through the following of the numerous streams to their sources, it also led to the rapid exploration of large tracts of remote country. The exploitation of these deposits has been carried on with varying degrees of success up to the present time by both manual and mechanical means, but the amount of gold now extracted is comparatively small.

A further factor in connection with the rivers is that, owing to the very successful acclimatisation of freshwater fish, notably trout, many of them now provide exceptionally fine fishing.

Lakes – In considering New Zealand's numerous lakes a distinction can be made, especially from the scenic viewpoint, between the lakes of the two Islands. Surrounded by extremely rugged country the larger lakes of the South Island are distinguished by the grandeur of their alpine settings, while those of the North Island, situated on a volcanic plateau, are of interest by reason of the neighbouring thermal activity. Owing to the excellence of their fishing, the North Island lakes possess an added tourist attraction. In both Islands the larger lakes are situated at high altitudes, and their consequent remoteness renders them unsuitable as a means of communication. In their functions as reservoirs the lakes of both Islands are of vital importance for the maintenance of the streams draining them and as a means of flood prevention. More especially is this the case where hydro-electric schemes are involved, Lakes Waikaremoana and Taupo in the North Island, and Lakes Coleridge, Pukaki, Tekapo, Wanaka, Hawea, and Wakatipu in the South Island, being of particular significance in this respect. A series of narrow man-made lakes have been produced in connection with hydro-electric development along some of the rivers.

Some particulars of the more important lakes are given in the following table.

| Lake | Length in Miles | Greatest Breadth, in Miles | Area, in Square Miles | Drainage Area, in Square Miles | Approximate Volume of Discharge, in Cubic Feet per Second | Maximum Height Above Sea Level in Feet (Range in Brackets)* | Greatest Depth, in Feet |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

*The range in lake levels is not available for all lakes. | |||||||

| NORTH ISLAND | |||||||

| Natural | |||||||

| Taupo | 25 | 17 | 234 | 1,270 | 4,490 | 1,172 (5) | 522 |

| Rotorua | 7 1/2 | 6 | 31 | 203 | .. | 920 (2) | 84 |

| Rotoiti | 10 | 3 | 13 | 248 | 852 | 916 (2) | 230 |

| Tarawera | 7 | 5 1/2 | 14 | 72 | 273 | 981 (2) | 285 |

| Rotoaira | 3 | 1 3/4 | 5 | 50 | 240 | 1,852 (3) | .. |

| Waikaremoana | 12 | 6 | 21 | 165 | 623 | 2,015 (45) | 840 |

| Wairarapa | 12 | 4 | 31 | 1,236 | .. | 5 | 64 |

| Rotoehu | 3 | 2 | 3 | 17 | .. | 968 (4) | .. |

| Rotoma | 3 1/4 | 2 1/4 | 4 1/2 | 12 | .. | 1,036 (6) | .. |

| Okataina | 4 | 3 | 4 | 25 | .. | 1,018 (9) | .. |

| Okareka | 1 1/2 | 1 1/4 | 1 1/4 | 8 | .. | 1,160 (4) | .. |

| Rotomahana | 4 | 1 | 3 1/2 | 27 | .. | 1,116 (22) | .. |

| Rerewhakaitu | 2 1/2 | 1 3/4 | 3 | .. | .. | 1,441 (4) | .. |

| Tikitapu | 1 | 3/4 | 1/2 | .. | .. | 1,364 | .. |

| Rotokakahi | 2 1/2 | 1 | 1 3/4 | 11 | 40 | 1,298 | .. |

| Artificial | |||||||

| Ohakuri | 21 | 1/4 | 5 1/2 | 1,850 | 5,540 | 942 | .. |

| Atiamuri | 4 | 1/4 | 1/2 | 1,980 | 5,830 | 826 | .. |

| Whakamaru | 13 1/2 | 1/2 | 3 | 2,155 | 6,160 | 742 | .. |

| Maraetai | 4 1/2 | 1/2 | 1 1/2 | 2,390 | 6,730 | 618 | .. |

| Waipapa | 6 | 1/4 | 1/2 | 2,500 | 7,010 | 417 | .. |

| Arapuni | 10 | 1/2 | 5 | 2,655 | 7,310 | 363 (2) | .. |

| Karapiro | 15 | 1/4 | 3 | 2,880 | 7,820 | 176 | .. |

| Whakamarino | 1/2 | 1/4 | 1/10 | .. | .. | 900 | .. |

| SOUTH ISLAND | |||||||

| Natural | |||||||

| Rotoiti | 9 | 1 1/2 | 4 | 71 | 440 | 2,020 (6) | 250 |

| Rotoroa | 5 1/2 | 2 | 9 | 145 | 960 | 1,462 (5) | 499 |

| Brunner | 5 1/2 | 5 1/2 | 15 | 160 | .. | 280 | 357 |

| Kaniere | 6 | 1 1/4 | 6 | 11 | .. | 429 | 646 |

| Coleridge | 11 | 2 | 14 | 216 | .. | 1,672 | 680 |

| Sumner | 6 | 1 1/2 | 5 1/2 | 130 | .. | .. | .. |

| Tekapo | 11 | 3 1/2 | 37 | 550 | 3,060 | 2,347 (25) | 620 |

| Pukaki | 9 1/2 | 5 | 32 | 523 | 4,520 | 1,640 (30) | .. |

| Ohau | 11 | 3 | 23 | 460 | 2,310 | 1,730 (9) | .. |

| Hawea | 19 | 5 | 46 | 567 | 2,240 | 1,133 (53) | 1,285 |

| Wanaka | 28 | 3 | 74 | 982 | 7,150 | 915 (14) | .. |

| Wakatipu | 48 | 3 | 113 | 1,150 | 6,160 | 1,017 (7) | 1,239 |

| Te Anau | 38 | 6 | 133 | 1,275 | 9,730 | 686 (15) | 906 |

| Manapouri | 18 | 5 | 55 | 1,785 | 13,630 | 608 (21) | 1,455 |

| Monowai | 12 | 1 | 11 | 105 | 495 | 643 (13) | .. |

| Hauroko | 22 | 1 1/2 | 27 1/2 | 225 | 1,100 | 513 (6) | .. |

| Poteriteri | 18 | 1 1/2 | 18 | 160 | 1,050 | 96 | .. |

| Waihola | 4 | 1 1/4 | 3 | 2,200 | .. | (Tidal) | 52 |

| Ellesmere | 14 | 8 | 70 | 745 | .. | (Tidal) | 7 |

| Artificial | |||||||

| Cobb | 3 | 1/4 | 3/4 | 28 | 198 | 2,650 (50) | .. |

| Waitaki | 3 | 1/2 | 2 1/2 | 3,750 | 12,150 | 753 | .. |

| Roxburgh | 20 | 1/4 | 2 1/4 | 6,012 | 17,270 | 430 | .. |

| Mahinirangi | 9 | 1 | 8 | 120 | 230 | 1,282 | .. |

GEOLOGY – The islands of New Zealand are part of the unstable circum-Pacific Mobile Belt; this is a region where volcanoes are active and where the earth's crust has long been buckling and breaking at a geologically rapid rate. The interplay, in the past, of earth movements and erosion has made the sedimentary rocks that cover almost three-quarters of New Zealand. Land areas that the earth movements have raised have been attacked by erosion, and the sand, mud, shingle, and other debris thus formed has been carried away to the sea, where it has accumulated in great thicknesses to form rocks such as sandstone, mudstone, greywacke, and conglomerate; the shells and other skeletons of sea creatures have accumulated to form thick layers of limestone. Many of the sedimentary rocks are in distinct layers called strata; earth movements have later raised them above the sea to form land, and the strata are in many places tilted and folded by pressure. Seas have advanced and retreated over New Zealand many times, and these sedimentary rocks represent almost every geological period since the Cambrian (see Time Scale); their age is revealed by the shells, foraminifera, and other fossils that they contain.

As well as sedimentary rocks, and volcanic rocks of various ages, New Zealand incorporates in its complex structure schist, gneiss, marble and other metamorphic rocks, and granite, diorite, gabbro, serpentine, and other intrusive igneous rocks. Most of these metamorphic and intrusive rocks are hundreds of millions of years old – they were formed at depth in the earth's crust early in New Zealand's history, in the “roots” of ancient mountain ranges, long ago destroyed, and are visible at the land surface today only because erosion has removed thousands of feet thickness of other rocks that once covered them. The metamorphic rocks developed when huge, elongated sea basins (geosynclines) were formed, in which tens of thousands of feet thickness of sediments accumulated; when these geosynclines were slowly compressed during major mountain-building episodes the deeper sediments were subjected to great pressure and shearing stress, which caused new minerals and structures to develop, changing the sediments into metamorphic rocks. The granites and other intrusive rocks are coarsely crystalline, and are usually considered to have been intruded into the outer crust in molten state during mountain building; some, however, may be the products of intense metamorphism of sediments.

GEOLOGICAL TIME SCALE

| Eras | Periods | Approximate Time Since Period Began (Years) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cenozoic | Holocene (Recent) | Quaternary | 10 thousand |

| Pleistocene | 1 million | ||

| Pliocene | 11 million | ||

| Miocene | Tertiary | 25 million | |

| Oligocene | 20 million | ||

| Eocene | 60 million | ||

| Paleocene | 70 million | ||

| Mesozoic | Cretaceous | 135 million | |

| Jurassic | 180 million | ||

| Triassic | 225 million | ||

| Paleozoic | Permian | 270 million | |

| Carboniferous | 350 million | ||

| Devonian | 400 million | ||

| Silurian | 400 million | ||

| Ordovician | 500 million | ||

| Cambrian | 600 million | ||

Geological History – Evidence of the earliest-known events in New Zealand's history is given by ancient rocks in Nelson, Westland, and Fiordland that were formed in the early Paleozoic era, perhaps as long as 600 million years ago (some in Westland may be older). They include thick, geosynclinal sedimentary rocks; this suggests that a large land mass existed at that time to yield the great volume of sediments, but little has been deduced about its shape or position.

The history of the later part of the Paleozoic era, and the Mesozoic era, is rather better understood; for a vast span of time from the Carboniferous period – probably until the early Cretaceous period – an extensive geosyncline occupied the New Zealand region. At first, during much of late Paleozoic time, huge quantities of submarine lava and volcanic tuff were included in the materials that accumulated in the geosyncline, but in the later Permian and Mesozoic times the sediments were mainly sand and mud, derived probably from some land west of present New Zealand; they were compacted into hard greywacke (a type of sandstone) and argillite (hard, dark mudstone).

In the early Cretaceous period one of the main mountain-building episodes in New Zealand's history took place: although geosynclinal sedimentation continued through the Cretaceous period in eastern New Zealand, the geosyncline elsewhere was compressed, and the sediments were intensely crumpled and broken and raised above the sea, probably forming a large, mountainous landmass. Some of the geosynclinal deposits, now exposed over much of Otago, alpine Westland, and parts of Marlborough Sounds, were metamorphosed into schist and gneiss by the tremendous deforming pressures to which the geosyncline was subjected.

The time that has elapsed since the intense folding of the strata in the New Zealand Geosyncline in the mid-Cretaceous period may be considered as the later geological history of this country; it embraces roughly 100 million years.

During the early part of this late history, erosion slowly wore down the mountains that had risen, producing a land of low relief. Over these worn-down stumps of the Mesozoic mountains the sea gradually advanced, beginning its transgression earlier in some areas than in others: in the early Cretaceous period it began to submerge land in the region of present North Auckland and the eastern margins of the North and South Islands, and thick deposits of mudstone and sandstone accumulated in some parts of these areas. At the close of the Mesozoic era, and in the very early Tertiary, land became so reduced in size and relief that little sediment was formed, and only comparatively thin deposits of fine bentonitic and sulphurous muds, and fine, white, foraminiferal limestone accumulated. In some areas New Zealand's main coal deposits accumulated, in swamps on the surface of the old land; these became buried by marine deposits as the sea continued its transgression in the Eocene period.

By the Oligocene period, most of the land was submerged, and in shallow waters free of land sediments thick deposits of shell and foraminiferal limestone accumulated. (Scattered, remnant patches of this Oligocene limestone furnish most of New Zealand's cement and agricultural lime.)

After the Oligocene submergence earth movements became more vigorous; many ridges rose from the sea as islands, and sank or were worn down again; sea basins formed and rapidly filled with sediments. New Zealand's late Tertiary environment has been described as follows: “The pattern of folds, welts and troughs that developed was on a finer scale than in the Mesozoic … the land moved up and down as a series of narrow, short, interfingering or branching folds. … we can think of Tertiary New Zealand as an archipelago. … a kind of writhing of part of the mobile Pacific margin seems to have gone on …*” The thick deposits of soft, grey mudstone and sandstone that now make up large areas of the North Island, and some parts of South Island, are the deposits that accumulated rapidly in the many sea basins, large and small, that developed in the later Tertiary.

Very late in the Cenozoic era – in the Pliocene and Pleistocene periods – one of the greatest episodes of mountain building in New Zealand's history took place. Earth movements became intense, and slowly pushed up the Southern Alps and other main mountain chains, and determined the general shape and size of the present islands of New Zealand. Much of the movement during this mountain building period (the Kaikoura Orogeny) took the form of displacement of blocks of the earth's crust along fractures called faults. The total movements of the earth blocks adjacent to major faults amounted to thousands of feet; it must have been achieved very slowly, probably by innumerable small movements, each of a few inches or feet. The blocks adjacent to “transcurrent” faults moved not only vertically but also laterally along the faults. The New Zealand landscape today in some regions shows well preserved tilted fault blocks bounded by fault-scarps – steep faces hundreds or even thousands of feet high. Fault movements continue to the present day, and have accompanied several major earthquakes of the past century. Many minor but revealing landscape features such as scarplets, fault ponds, and shutter ridges show where movement has been occurring in recent centuries.

Erosion during this time has eaten into the major landscape forms that the earth movements have built, carving the detailed landscape pattern of peaks, ridges, valleys, and gorges, and has built up alluvial plains, shingle fans, and other constructional forms; at the coast, waves have driven back the headlands, and built beaches, spits, and bars. The Pleistocene period was the time of the Ice Age, and in the high mountains of the South Island glaciers carved deep valleys and carried huge loads of rock, dumping them as moraines. The late Pleistocene glaciers carved the fiords of Fiordland and the basins occupied by most South Island lakes; there were small glaciers also on Ruapehu, where remnants survive, and on Mount Egmont and the Tararua Range.

*“New Zealand Biogeography” by Charles A Fleming. Tuatara Vol. 10, No. 2, June 1962, pp. 53–108.

Volcanic activity of the past few millions of years has played an important part in making the rocks and shaping the landscape of parts of the central and northern North Island; Banks Peninsula, a twin volcanic dome in Canterbury, achieved much of its growth then, too. The largest volcanic outpourings of late geological times in New Zealand have been in the region between Tongariro National Park and the Bay of Plenty Coast: andesite lava, scoria, and ash were erupted in the Pleistocene period and later to build the huge volcanoes, Ruapehu, Tongariro, and Ngauruhoe; more than 2,000 cubic miles of molten rhyolitic magma was erupted in the form of ignimbrite, pumice, and rhyolite lava, building up the Volcanic Plateau.

The Geological Survey, Department of Scientific and Industrial Research has built up this body of geological knowledge.

Geological Maps – The geological maps show the present distribution of major rock groups in New Zealand, brought about by the events and processes that have been summarised in previous paragraphs. (These maps were originally prepared for the New Zealand Encyclopaedia.)

Older Rocks – Much of the late Cretaceous and Tertiary sedimentary rock that once must have covered a large part of the South Island has been worn off by erosion since the Kaikoura Orogeny, and the “undermass” of old rocks has been exposed.

The oldest of these rocks lie to west: Fiordland is made up mainly of metamorphic diorite, granite, and coarse schist, gneiss, and marble, with Ordovician graptolite-bearing slates in its southwest extremity; greywackes and argillites of possibly pre-Cambrian age occur in Westland and southwest Nelson, and further north in Nelson there are large areas of complexly folded Cambrian and Ordovician sedimentary and metamorphic rocks. Large granitic masses, hundreds of square miles in area, occur in Westland, Nelson, and Stewart Island.

These ancient rocks terminate with an abrupt boundary (which shows clearly even on this small-scale map) extending from Milford Sound along the western margin of the Southern Alps. This boundary is the Alpine Fault, a great fracture that divides the South Island into two areas of dissimilar geological structure: to the west of it, and in Fiordland, are the granites and other ancient rocks just described; to the east, the undermass rocks are predominantly the sedimentary and marine volcanic rocks of the New Zealand Geosyncline, and their metamorphosed forms, of later Paleozoic and Mesozoic age. From Marlborough, through Canterbury to North Otago, the map shows an almost continuous expanse of these rocks; here they are mainly sparsely fossiliferous greywackes and argillite strata of Triassic and Jurassic age. On the Western flanks of the Southern Alps, and in Otago, these sedimentary rocks merge gradually with schist and gneiss. Those of the Southern Alps show on the map as a very narrow belt, cut off by the Alpine Fault, but the southern schists form a belt some 60 miles wide extending for about 150 miles across Otago. To the south, also, this schist mass merges gradually with sedimentary rocks of the New Zealand Geosyncline, here of Permian age: these strata, mainly tuffs and tuffaceous greywackes forming a belt that stretches across Southland, are the northern limb of a major downfold or syncline; Triassic and Jurassic strata occupy its core, making up much hill country of Southland. The southern limb rocks include much marine volcanic rock, and in the core of the syncline in western Southland a belt of dunite and serpentine is intruded and is well exposed in the Olivine and Red Hill ranges.

A sequence of rocks very like that of Southland is found also in eastern Nelson; here, fossiliferous Triassic rocks and Permian sedimentary and volcanic rocks closely resembling those of Southland are found, and a belt of dunite and serpentine (the Nelson “mineral belt”) intrudes them. It has been suggested that the Nelson and Southland rocks, which terminate abruptly at the Alpine Fault and its continuation as the Wairau Fault, were originally joined, and have been displaced some 300 miles by lateral movement at the fault.

Younger Rocks – On the eastern side of the South Island, upper Cretaceous and Tertiary strata survive only as small patches, the remnants of a once fairly complete cover of younger rocks. Thick geosynclinal Cretaceous strata are found in the Clarence and Awatere Valleys of Marlborough, but elsewhere in the eastern South Island the upper Cretaceous and lower Tertiary strata are thin. They include foraminiferal limestone, greensands, sandstones, and other shell deposits formed during slow transgression by the sea. Oligocene limestone remnants mark the period of maximum transgression.

On the western side of the South Island the younger rocks are more widespread, and include some thick sequences that were formed in rapidly sinking basins. The oldest are the coal measures, mainly Eocene in age. They are overlain in some areas by thick lower Tertiary marine strata. In Southland, thick Tertiary strata occupy the Waiau Syncline, between Lake Te Anau and Foveaux Strait.

The map shows some large areas of Pleistocene to Recent terrestrial deposits in the South Island. The largest forms the Canterbury Plains, and consists of old shingle deposits of unknown thickness washed from the Southern Alps during the Pleistocene glaciation. Others occupy the Moutere depression of Nelson, and form Southland Plains, and intermontane basins, such as the McKenzie Plains, in the main mountain chains. Thick Pleistocene moraines form the main surface rocks of South Westland.

Banks Peninsula is the only large mass of young volcanic rocks in the South Island; there are smaller areas at Timaru, Oamaru, and in the Dunedin district.

Older Rocks – Unlike the South Island, the North Island has no large expanses of granite or of metamorphic rocks: the undermass rocks are almost wholly complexly folded and faulted greywackes and argillites of the New Zealand Geosyncline, predominantly Mesozoic in age.

The largest expanse of these hard rocks forms the main mountain backbone of the North Island, extending from Cook Strait to the East Cape area. Smaller areas of them are exposed between north Taranaki and Auckland; they include the richly fossiliferous strata of the Kawhia Syncline, a major downfold of the undermass rocks.

In North Auckland, deeply weathered undermass rocks, in part of Permian age, form low hill country in the east, particularly between Whangaroa and Whangarei harbours.

Younger Rocks – Over most of the North Island the older rocks are hidden by Cretaceous, Tertiary, and Quaternary sedimentary rocks and by young volcanic rocks. In some areas the younger sedimentary rocks are thin and patchy; in others they are many thousands of feet thick over hundreds of square miles. The bulk of them are poorly consolidated sandstones, and grey mudstones to which the colloquial name “papa rock” is often applied.

The main areas with thick sequences of these young strata are the Taranaki - Wanganui - Rangitikei district, and the region east of the main ranges, including most of the Gisborne, Hawke's Bay, and Wairarapa districts. In both areas intensive oil prospecting of recent years has greatly added to knowledge of the structure.

In the Taranaki - Wanganui - Rangitikei district the strata dip gently south, so that increasingly young rocks are exposed in this direction, the lower Tertiary being seen only in the north. However, recent oil bores drilled to depths of about 13,000 ft at Kapuni in Taranaki, passed through a full sequence of strata from Pleistocene through all Tertiary stages, finally reaching Eocene coal measures.

In the eastern North Island the structure of the younger rocks is much more complex than in the western area. Upper Cretaceous strata are followed by Tertiary in many sedimentary basins large and small, with many unconformities. The southern part of the region is broken by many transcurrent faults, and hard lower Cretaceous greywacke piercement bodies project from the younger rocks.

Younger rocks of South Auckland do not form such large basins as those just described. The oldest of these strata are the Eocene coal measures of the Waikato region. Upper Cretaceous strata, mainly mudstones, are the most widespread of the younger rocks of North Auckland.

Young volcanic rocks are widespread in the North Island. The largest area of them is the Central Volcanic District: north of the three great andesite volcanoes, Ruapehu, Ngauruhoe, and Tongariro, lies the “volcanic plateau”, an expanse of some 10,000 square miles made up of several thousand cubic miles of ignimbrite, rhyolite lava, and pumice. This is one of the largest and youngest accumulations of acid volcanic rocks in the world. Most of it has been erupted in late Pliocene and Pleistocene times. The belt of most recent activity in the Central Volcanic District is known as the Taupo Volcanic Zone; it contains all this country's active volcanoes, many inactive ones, and all the geysers and boiling springs.

Mount Egmont is a huge, conical, andesite volcano, with the remnants of two other volcanic cones nearby; all are of Pleistocene age. In the Waikato there are eroded Pleistocene cones of approximately basic andesite composition; the largest is Pirongia, some 3,000 ft high. Auckland city and the area immediately to the south has been the scene of many eruptions of basalt lava and scoria in late Pleistocene and Holocene times; many small scoria cones are seen at Auckland city. Late Tertiary and Quaternary basaltic eruptions in North Auckland have built lava plateaus and many young scoria cones.

A Descriptive Atlas of New Zealand contains geological maps of New Zealand and summaries of New Zealand's geology and landscape development. New Zealand Geological Survey Bulletin 66, The Geological Map of New Zealand, 1:2,000,000, is a lengthier summary with a more detailed geological map and cross sections.

G.C.S.

EARTHQUAKES: Geophysical Background – Earthquakes are geographically associated with active volcanoes and with major earth movements such as mountain building; these three types of disturbance are confined, for the most part, to certain limited regions of the world. Such disturbed regions, of which New Zealand is one, are evidently the site of some kind of development affecting the outer shell of the Earth. Little is yet known about the internal processes that give rise to these geophysical disturbances, nor are the relations connecting them understood in any detail.

Formerly earthquakes were believed to be caused by volcanic activity, but it is now recognised that volcanic earthquakes are restricted to small shocks in the immediate vicinity of the volcanism. In New Zealand, tremors of this kind are experienced in the zone of active volcanism that extends from Mount Ruapehu to White Island.

In some places geological faulting at the surface gives visible evidence that a major earth movement has occurred. Occasionally movement on a fault has been observed to occur simultaneously with an earthquake in the same vicinity. New Zealand provided one of the earliest examples of this to become generally known, when movement took place on the Wairarapa Fault at the time of the great Wellington earthquake of 1855. Such events as this have led to the idea that earthquakes in general are caused by fault movements, but it has proved difficult to find convincing evidence in support of this theory. It is noteworthy that there seems to be little earthquake activity along much of the Alpine Fault, which has been traced for 300 miles from Milford Sound to Lake Rotoiti and is classed by geologists as one of the largest and most active faults in the world. The nature of the connection between earthquakes and faulting is still somewhat obscure.

The great majority of the world's earthquakes occur at depths of less than 40 miles, and in many earthquake zones there are no shocks at any greater depth. A moderate number of New Zealand earthquakes are classed as intermediate in depth, i.e., originating at between 40 miles and 190 miles deep. The two deepest New Zealand earthquakes recorded so far occurred four and a half minutes apart on 23 March 1960, with a common focus 370 miles deep under north Taranaki; this is about 80 miles shallower than the deepest earthquake known.

It is difficult to compare the degree of earthquake activity in New Zealand with that in other regions because of the many differences that arise in earthquake type and mode of occurrence. New Zealand and California are often regarded as roughly similar, with an activity very much less than, for example, Japan or Chile.

Regional Distribution – There are two separate regions of earthquake activity in New Zealand. The larger, northern region may be roughly defined as lying between latitude 36 1/2°S and 43 1/2°S. It thus includes the northern half of the South Island, and all the North Island apart from the North Auckland peninsula; but the area from Kaipara Harbour to the lower Waikato River should be excluded. The southern active region lies to the west of longitude 169 1/2°E, and incorporates Southland, western Otago, and southern Westland. Earthquakes have only occasionally been located in the parts of New Zealand lying outside these two regions.

Within the active regions the occurrence of shallow earthquakes is widely scattered. There has been a tendency, however, for the larger shallow earthquakes to lie towards the Pacific side of the northern active region and towards the Tasman side of the southern active region. Earthquakes with deeper foci are mostly confined to a narrow belt in the northern region, extending from the Bay of Plenty south-westwards to Tasman Bay.

The historical record is too brief to support a quantitative assessment of the frequency with which one might expect earthquakes to be felt at a given intensity in various parts of New Zealand. Considering the distances to which major earthquakes can be effective, in relation to the size of New Zealand, it would be imprudent to regard any part of the country as permanently exempt from the possibility of earthquake damage.

Outside the active regions there are many areas, however, where no damaging intensity has actually been experienced in historical times. Moreover, since the major shallow earthquakes on record have been rather widely distributed within the active regions, there appears to be no particular area of markedly intense seismicity.

The Hawke's Bay earthquake of 3 February 1931 resulted directly or indirectly in 255 deaths. The total of deaths that have been recorded as due to other earthquakes since 1848 is 29.

Seismological Observatory – Earthquake recorders are operated continuously at the following stations by the Seismological Observatory, Wellington: Apia and Afiamalu (Samoa); Raoul Island (Kermadecs); Suva (Fiji); Onerahi, Auckland, Karapiro, Tuai, Gisborne, Wairakei, Tarata, Tongariro, Bunnythorpe, and Wellington (North Island); Cobb, Kaimata, Gebbies Pass, Roxburgh, and Monowai (South Island); Hallett Station and Scott Base (Antarctica). The installations at the following stations include instruments for recording distant earthquakes: Afiamalu, Suva, Auckland, Wellington, Roxburgh, Hallett, Scott Base. At the Samoan and Antarctic stations preliminary readings are made locally and notified by radiogram. The analysis of records from all stations is carried out at the Observatory in Wellington.

The Observatory publishes regular reports of all significant earthquakes occurring in the New Zealand region; in a normal year there are about 200 such earthquakes, and about 100 of these are reported felt. The analysis involves using observations from stations in other countries as well as those from the local network, and the Observatory likewise contributes data to the international seismological agencies about distant earthquakes as well as large local ones. Details of tremors felt in New Zealand are supplied to the public and the press. In the study of felt earthquakes the instrumental results are augmented by “felt reports”; these are supplied by a large number of voluntary observers throughout New Zealand in response to a standard questionnaire issued by the Observatory.

Earthquake data are used by the Observatory for studying the fundamental characteristics of the Earth's crust in New Zealand, Antarctica, and the neighbouring oceanic regions, and also for contributing to geophysical knowledge of the Earth's deep interior.

Principal Earthquakes During the Year 1963 – The largest earthquake of the year, of magnitude 6.0 (Richter scale), occurred on 12 April 1963, in the Huiarau Range between Lake Taupo and Lake Waikaremoana. This earthquake was felt widely in the central parts of the North Island and caused slight damage at Minginui and Tarawera.

On 15 July a deep earthquake was felt extensively in the southern part of the North Island, and the northern part of the South Island; it originated in Southern Taranaki at a depth of 100 miles, and had a magnitude of 5.9.

Two earthquakes of exceptional interest occurred late in the year in the far north of New Zealand. Centred near Mangonui, 70 miles north of Whangarei, they are the only earthquakes known to have originated in Northland except for a series of minor shocks in the Bay of Islands in 1919. The first earthquake, of magnitude 3.2, took place on 17 November and was felt at various places out to 20 miles from Mangonui. The second was of magnitude 5.2 and took place on 23 December. This shock was felt over almost the entire peninsula north of Kaikohe and damage was done to chimneys, water tanks and house foundations over an area some ten miles across, including Peria, Oruaiti, Otangaroa and Totara North.

A number of large earthquakes took place during the year near the Kermadec Islands to the north of New Zealand, the largest having a magnitude of about 7. Several of these shocks were felt at Raoul Island during the last week of March.

WEATHER INFORMATION – The collection of weather information and the provision of weather forecasts and climatic data for diverse interests in aviation, shipping, agriculture, Government Departments, and the general public are functions of the New Zealand Meteorological Service. By arrangement with the administrations concerned the Service performs similar functions for British territories in the Pacific.

Weather reports for use in forecasting are made at about 110 places within New Zealand and 50 in Pacific islands and collected by telegraph and radio, along with measurements of winds at upper levels made at eight radar wind-measuring stations and of temperatures made at seven radiosonde stations. Daily observations are made for climatological purposes at about 180 places in New Zealand and 60 in the islands. Rainfall measurements are made at a total of about 1,400 places within New Zealand and 110 outside the country.

Detailed climatological statistics are published annually in the Meteorological Observations. Current statistics appear monthly in a climatological table included in the New Zealand Gazette.

CLIMATE – Situated between 34°S and 47°S the main islands lie within the broad belt of strong westerly winds which encircles the hemisphere south of about latitude 35°S. Just to the north is the high-pressure ridge of the subtropics from which barometric pressure decreases southwards over New Zealand to the deep low-pressure trough located near latitude 60°S.

In the Australasian region there is no semipermanent anticyclone, as exists in subtropical latitudes in the Indian and eastern Pacific Oceans. Instead, a continual eastward migration of anticyclones takes place, roughly at weekly intervals. Most of the centres pass over or to the north of the North Island. The low-pressure troughs which separate successive anticyclones are associated with deep depressions centred far to the south. A period of disturbed weather accompanies the trough with a change to cold southerly or south-westerly winds as it advances north-eastwards over New Zealand. Conditions improve again with the approach of the next anticyclone from the west. While this simple progression dominates the day-to-day weather, the situation frequently becomes much more complex. The troughs are unstable systems where depressions commonly form, some of which develop into vigorous storms that travel south-eastwards across New Zealand.

The anticyclones themselves continually vary in size, intensity, and rate of movement. Their tracks are furthest north in the spring, on the average, and reach their southern limit in late summer or early autumn when most of the centres cross central or southern New Zealand. At this time of the year, too, northern and eastern districts of the North Island occasionally come under the influence of deep cyclones of tropical origin.

The other main factors which influence the climate of New Zealand are, first, its position in the midst of a vast ocean, and second, the shape and topography of the country itself.

Australia, the nearest continent, is 1,000 miles to the west; Antarctica is 1,400 miles to the south. Hot air masses from the interior of Australia in summer, or freezing air masses from the Antarctic, which occasionally reach New Zealand, retain little of their original character after their long ocean passage. Thus, there is an absence of extreme variations of temperature. On the other hand, since abundant supplies of moisture are supplied by evaporation from the oceans, and depressions are frequent and vigorous, the average precipitation is high.

The chain of high mountains, which extends from south-west to north-east through the length of the country, rises as a formidable barrier in the path of the prevailing westerly winds. The effect is to produce much sharper climatic contrasts from west to east than in the north-south direction. In some inland areas of the South Island just east of the mountains the climate is distinctly continental in character, despite the fact that no part of New Zealand is more than 80 miles from the sea.

Winds – Winds from a westerly quarter prevail in all seasons, with a general tendency to increase in strength from north to south. However, considerable local modifications to the general air flow occur during its passage across the mountainous terrain. Approaching the main ranges the flow from the west turns towards the north-east and on descending on the eastern side swings towards the southeast. This results in an increased number of south-westerlies in Westland and a predominance of north-westerlies in inland districts of Otago and Canterbury, where strong gales from this quarter occur at times in the late spring and summer. Daytime sea breezes usually extend from the coast inland for 20 miles or more during periods of settled weather in summer. On the Canterbury coast the wind comes most frequently from the north-east, partly because there is a persistent sea breeze from this quarter, but south of Dunedin south-westerlies predominate. Cook Strait, the only substantial gap in the main mountain chain, acts as a natural funnel for the air flow and is a particularly windy locality afflicted by gales from the south-east as well as the north-west. This “funnel” effect is also in evidence about Foveaux Strait. North of Taranaki the general air flow is more from the south-west, and there is a noticeable reduction in windiness in the summer.

An indication of the variation in the frequency of strong winds from summer to winter, and in different parts of the country, is given in the next table. These were all obtained by the use of Dines pressure-tube anemometers at well exposed sites, mostly aerodromes.

| Station | Average Number of Days With Gusts Reaching | Years of Data | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 m.p.h. or More | 60 m.p.h. or More | ||||||

| Nov–Apr | May–Oct | Year | Nov–Apr | May–Oct | Year | ||

| NOTE – These are all aerodromes, with the exception of Auckland (Mechanics Bay) and Wellington (Kelburn). | |||||||

| Kaitaia | 9 | 23 | 32 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 8 |

| Auckland (Mechanics Bay) | 22 | 30 | 52 | 0.8 | 1.6 | 2.4 | 19 |

| Rotorua | 6 | 7 | 13 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 16 |

| Hamilton | 9 | 13 | 22 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 8 |

| Gisborne | 17 | 24 | 41 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 16 |

| New Plymouth | 35 | 49 | 84 | 2.7 | 5.3 | 8.0 | 19 |

| Palmerston North | 25 | 23 | 48 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 12 |

| Wellington (Kelburn) | 78 | 73 | 151 | 17.4 | 11.2 | 28.6 | 8 |

| Nelson | 21 | 15 | 36 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 18 |

| Blenheim (Woodbourne) | 24 | 17 | 41 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.6 | 12 |

| Hokitika | 16 | 19 | 35 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 3.2 | 14 |

| Christchurch | 31 | 26 | 57 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 3.3 | 16 |

| Taieri | 31 | 26 | 57 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 2.8 | 18 |

| Invercargill | 51 | 40 | 91 | 5.2 | 4.4 | 9.6 | 14 |

Rainfall – The distribution of rainfall is mainly controlled by mountain features, and the highest rainfalls occur where the mountains are exposed to the direct sweep of the westerly and north-westerly winds. The mean annual rainfall (see map) ranges from as little as 13 in. in a small area of Central Otago to over 300 in. in the Southern Alps. The average for the whole country is high, but for the greater part it lies between 25 and 60 in., a range regarded as favourable for plant growth in the temperate zone. The only areas with under 25 in. are found in the South Island, to the east of the main ranges. These include most of Central and North Otago, and South Canterbury. In the North Island, the driest areas are southern Hawke's Bay, Wairarapa, and Manawatu where the average rainfall is 30–40 in. a year. Of the remainder, much valuable farm land, chiefly in northern Taranaki and Northland, has upwards of 60 in. Over a sizeable area of both Islands rainfall exceeds 100 in. a year but, with the exception of Westland, this is mountainous and unoccupied, much of it being forest covered.

For a large part of the country the rainfall is spread evenly through the year, although its effectiveness in summer is, of course, much reduced. The greatest contrast is found in the north, where winter has almost twice as much rain as summer. This predominance of winter rainfall diminishes southwards. It is still discernible over the northern part of the South Island but, over the southern half, winter is the season with least rainfall, and a definite summer maximum is found inland due to the effect of convectional showers. The rainfall is also influenced by seasonal variations in the strength of the westerly winds. Spring rainfall is increased in and west of the ranges as the westerlies rise to their maximum about October, while a complementary decrease occurs at the same time in the lee of the ranges.

Areas which are exposed to the west and south-west experience much showery weather, and rain falls on roughly half the days of the year. Over most of the North Island rain can be measured on at least 150 days a year except to the east of the ranges where there are, in places, fewer than 125 rain days. Those areas of the South Island with annual rainfall under 25 in. generally have about 100 rain days a year. In the far south the frequency of rain increases sharply; in Stewart Island and Fiordland rain days exceed 200 a year. Over most of the country between 55 and 65 per cent of the rain days also qualify as wet days (0.10 in. or more). The percentage increases to over 70 in Westland, but in the low rainfall area of inland Otago there are only about 40 wet days a year compared with 100 rain days.

On the whole the seasonal rainfall does not vary greatly from year to year, the reliability in spring being particularly advantageous for agricultural purposes. It is least reliable in late summer and autumn when very dry conditions may develop east of the ranges, particularly in Hawke's Bay.

The highest daily rainfall on record is 22 in., which occurred at Milford Sound where the mean annual rainfall is 250 in. Other areas with considerably lower rainfall are also subject to very heavy daily falls; such areas are to be found in northern Hawke's Bay and in north-eastern districts of the Auckland Province. By contrast, in the Manawatu district and in Otago and Southland daily falls reaching 3 in. are very rare.

NORMAL MONTHLY AND ANNUAL RAINFALL (INCHES) (1921–50)

| Station | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Te Paki, Te Hapua | 3.3 | 3.6 | 3.3 | 5.6 | 6.5 | 7.2 | 7.3 | 5.6 | 4.5 | 3.8 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 56.8 |

| Auckland | 3.3 | 4.1 | 2.8 | 4.3 | 4.8 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 4.3 | 3.8 | 4.2 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 48.9 |

| Tauranga Airport | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.8 | 5.0 | 4.9 | 5.6 | 5.0 | 4.8 | 3.8 | 4.6 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 51.2 |

| Ruakura, Hamilton | 3.3 | 3.2 | 2.9 | 4.0 | 4.3 | 4.9 | 4.6 | 4.1 | 3.7 | 4.3 | 3.7 | 2.9 | 45.9 |

| Rotorua | 4.4 | 3.9 | 3.4 | 4.6 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 4.6 | 4.8 | 4.4 | 4.9 | 3.9 | 3.8 | 53.7 |

| Gisborne Airport | 2.8 | 3.2 | 3.0 | 3.4 | 5.0 | 3.9 | 4.9 | 3.9 | 2.9 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 39.8 |

| Lake Waikaremoana | 6.2 | 6.1 | 6.0 | 6.7 | 8.6 | 7.3 | 7.7 | 7.0 | 6.0 | 5.4 | 5.2 | 4.7 | 76.9 |

| New Plymouth | 4.7 | 4.1 | 3.7 | 5.0 | 5.3 | 6.4 | 6.2 | 5.9 | 4.8 | 5.8 | 4.5 | 4.8 | 61.2 |

| Napier | 2.6 | 2.8 | 2.2 | 2.7 | 3.8 | 3.1 | 3.5 | 2.8 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 31.2 |

| Wanganui | 2.7 | 3.0 | 2.2 | 2.8 | 3.1 | 3.4 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 2.5 | 3.2 | 2.7 | 2.9 | 34.4 |

| Palmerston North | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.4 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 3.9 | 3.1 | 3.5 | 2.9 | 3.8 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 39.0 |

| Masterton | 2.5 | 2.7 | 2.2 | 2.7 | 4.1 | 4.0 | 3.9 | 4.2 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 38.0 |

| Wellington (Kelburn) | 2.8 | 3.5 | 3.0 | 3.6 | 4.5 | 4.6 | 4.9 | 5.1 | 3.7 | 4.6 | 3.1 | 4.1 | 47.5 |

| Nelson Airport | 2.7 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 3.0 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 2.9 | 3.6 | 2.9 | 3.6 | 2.7 | 3.1 | 35.9 |

| Blenheim | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 25.8 |

| Hanmer | 3.5 | 3.7 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 4.8 | 3.5 | 3.7 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.3 | 3.3 | 3.8 | 45.3 |

| Hokitika | 9.8 | 8.6 | 8.4 | 8.8 | 9.0 | 8.0 | 8.3 | 9.3 | 8.3 | 10.9 | 9.5 | 9.9 | 108.8 |

| Lake Coleridge | 2.6 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 2.4 | 2.8 | 33.0 |

| Christchurch | 2.2 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 3.0 | 2.7 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.4 | 26.3 |

| Timaru | 2.5 | 2.5 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 2.9 | 23.5 |

| Milford Sound | 25.5 | 23.1 | 22.3 | 21.8 | 21.6 | 14.7 | 14.7 | 17.3 | 19.8 | 26.0 | 23.1 | 23.4 | 253.3 |

| Queenstown | 3.2 | 2.5 | 3.0 | 2.9 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 3.0 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 31.6 |

| Alexandra | 1.8 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 13.2 |

| Dunedin(Musselburgh) | 2.8 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 31.0 |

| Invercargill Airport | 3.6 | 3.8 | 4.3 | 3.8 | 3.7 | 3.9 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 42.8 |

Thunderstorms – Thunderstorms are not numerous. Their frequency is greatest in the north and west where thunder is heard on 15 to 20 days a year; east of the ranges (except in Gisborne) the figure is five or less.

Hail – Hail is most frequent in the south-west where it is reported on about 20 days a year, but for the greater part of the country it occurs on about five days a year or less. Most of the hailstones are small, but occasionally large stones cause local damage to glasshouses, and to orchards and market gardens, chiefly in Canterbury and Hawke's Bay.

Temperature – Mean temperatures at sea level decrease steadily southwards from 59°F in the far north to 54° about Cook Strait, then to 49° in the south. With increasing altitude, temperatures drop about 3° per 1,000 ft. January and February, with approximately the same mean temperature, are the warmest months of the year; July is the coldest. Some temperature statistics for selected places are included in the table on climatological averages. Highest temperatures are recorded east of the main ranges, where they rise to the nineties on a few afternoons in most summers, usually in association with a north-westerly Föhn wind. The extremes for New Zealand (measured in a standard thermometer screen) are 101° at Ashburton and – 3° at Ophir (Central Otago).

As is to be expected, there is a small annual range of temperature (difference between mean temperature of the warmest and coldest months). In Northland and in western districts of both Islands the annual range is about 15°F. For the remainder of the North Island, and east coast districts of the South Island, it is 17°–19°. Further inland it exceeds 20° in places, reaching a maximum of 25° in Central Otago where there is an approach to a continental type of climate.

Frost – It is well known that local variations in frostiness are considerable, even within quite small areas. On a calm, clear night the cold air in contact with a sloping surface gravitates slowly downhill to collect in valleys and depressions, and it is these “Katabatic” drifts which are mainly responsible for local temperature variations at night. Gently sloping ground with a northerly aspect tends to be least affected by frost. Favourable sites in coastal areas of Northland are free of frost, although further inland light frosts occur frequently in the winter months. At Albert Park, Auckland, the screen minimum thermometer (4 ft above the ground) has registered below 32°F only once in nearly 50 years, yet across the harbour at Whenuapai Aerodrome there are eight screen frosts per annum on the average. Excluding the uninhabited mountainous areas, the most severe winter conditions are experienced in Central Otago and the Mackenzie Plains of inland Canterbury, and on the central plateau of the North Island. Even in these areas night temperatures as low as 10° are rarely recorded. Elsewhere over the North Island the winters are very mild and pastures maintain continuous growth. In both Islands sheep and cattle remain in the open all the year round.

Snow – The majority of New Zealanders rarely see snow except on the mountains. The North Island has a small permanent snow field above about 8,000 ft on the central plateau, but the snow line rarely descends below 2,000 ft even for brief periods in winter. In the South Island snow falls on a few days a year in eastern coastal districts and in some years may lie for a day or two even at sea level. In Westland it does not lie at sea level. The snow line on the Southern Alps is around 7,000 ft in summer, being slightly lower on the western side where the Franz Josef and Fox Glaciers descend through heavy bush to within 1,000 ft of sea level. In inland Canterbury and Otago, where there are considerable areas of grazing lands above 1,000 ft, snowfalls are heavier and more persistent and have caused serious losses of sheep during severe winters in the past. However, only rarely does the winter snow line there remain permanently below 3,000 ft.

Relative Humidity – Humidity is commonly between 70 and 80 per cent in coastal areas and about 10 per cent lower inland. It varies inversely to the temperature, falling to a minimum in the early afternoon when temperature is highest and frequently lying between 90 and 100 per cent during clear nights. As the following table shows, the diurnal variation is greater than the difference between summer and winter.

| Station | Mean Relative Humidity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | July | |||

| 3 a.m. | 3 p.m. | 3 a.m. | 3 p.m. | |

| per cent | ||||

| Auckland (Mechanics Bay) | 85 | 63 | 90 | 74 |

| Gisborne | 89 | 62 | 90 | 72 |

| Ohakea Aerodrome | 87 | 62 | 89 | 72 |

| Wellington | 89 | 71 | 87 | 77 |

| Christchurch | 87 | 61 | 89 | 73 |

| Hokitika | 95 | 78 | 93 | 75 |

| Invercargill | 90 | 72 | 91 | 78 |

Very low humidities – between 20 and 30 per cent or lower – occur at times in the lee of the Southern Alps where the Föhn effect is often very marked. In summer the hot, dry “Canterbury Norwester” is generally a most unpleasant wind. Cool south-westerlies are also at times very dry when they reach eastern districts. In Northland the humid mid-summer conditions are inclined to be rather oppressive though temperatures rarely reach 85°. Dull, humid spells are generally not prolonged anywhere, but their frequency shows a marked increase in the south.

Sunshine – The sunniest areas are to be found locally near Blenheim, Nelson, and Whakatane, where the average duration of bright sunshine exceeds 2,400 hours per annum. Napier and the rest of the Bay of Plenty are only slightly less sunny. A large portion of the country is favoured with at least 2,000 hours. Even Westland, despite its high rainfall, has 1,800 hours. Southland, where sunshine drops sharply to 1,700 hours per annum, lies on the northern fringe of a broad zone of increasing cloudiness. Four hundred miles further to the south at Campbell Island the sunshine has the extremely low value of 650 hours per annum. A pleasant feature of the New Zealand climate is the high proportion of sunshine during the winter months. To eliminate the effect of varying day-length the summer and winter sunshine at a few selected stations have been expressed as a percentage of the possible sunshine.

| Summer | Winter | |

|---|---|---|

| per cent | ||

| Auckland | 57 | 49 |

| Hamilton | 52 | 44 |

| New Plymouth | 53 | 47 |

| Napier | 57 | 52 |

| Wellington | 52 | 42 |

| Nelson | 58 | 57 |

| Hokitika | 43 | 44 |

| Christchurch | 46 | 45 |

| Dunedin | 41 | 43 |

| Invercargill | 42 | 35 |

As these figures indicate, there is a marked increase in cloudiness in the North Island in winter, but little seasonal change in the South Island, except in Southland.

Climatological Averages – The following table provides a brief summary of the main climatological elements for selected locations.

| Station | Altitude | Annual Averages | Air Temperature (Degrees Fahrenheit) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rain Days (0.01 in. or More) | Wet Days (0.10 in. or More) | Bright Sunshine | Days of Screen Frost (min. air temp. less than 32°F) | Mean Temp. | Mean Daily Maxmium | Mean Daily Minimum | Mean Annual | |||||

| Jan | Jul | Jan | Jul | Maximum | Minimum | |||||||

NOTE: (1) Averages of rain days and wet days 1950–59; sunshine 1935–60; mean temperature 1931–60; other temperature data and days of screen frost, various periods – all exceeding 10 years. (2) For normal monthly and annual rainfall for these stations, see table under subsection on Rainfall. | ||||||||||||

| ft. | hours | |||||||||||

| Te Paki, Te Hapua | 190 | 187 | 112 | 2,140 | 2 | 59.3 | 73 | 60 | 57 | 46 | 78 | 30 |

| Auckland | 160 | 173 | 100 | 2,090 | 0 | 59.5 | 73 | 57 | 60 | 46 | 81 | 37 |

| Tauranga Airport | 12 | 152 | 91 | 2,320 | 9 | 57.2 | 75 | 57 | 55 | 40 | 85 | 29 |

| Ruakura, Hamilton | 131 | 168 | 99 | 1,980 | 29 | 55.4 | 74 | 56 | 52 | 37 | 85 | 23 |

| Rotorua | 1,006 | 151 | 96 | 2,000 | 26 | 53.7 | 74 | 54 | 52 | 36 | 87 | 24 |

| Gisborne Airport | 13 | 158 | 83 | 2,210 | 8 | 56.8 | 76 | 57 | 55 | 40 | 91 | 28 |

| Lake Waikaremoana | 2,110 | 196 | 132 | .. | 5 | 51.7 | 68 | 48 | 52 | 37 | 83 | 30 |

| New Plymouth | 160 | 166 | 113 | 2,110 | 1 | 56.1 | 69 | 55 | 56 | 43 | 78 | 32 |

| Napier | 5 | 124 | 62 | 2,280 | 8 | 57.1 | 74 | 55 | 57 | 39 | 89 | 29 |

| Wanganui | 72 | 146 | 87 | 2,120 | 4 | 56.1 | 71 | 54 | 56 | 41 | 83 | 30 |

| Palmerston North | 110 | 172 | 94 | 1,810 | 16 | 55.0 | 71 | 53 | 55 | 39 | 82 | 27 |

| Masterton | 340 | 172 | 92 | 2,060 | 30 | 53.9 | 74 | 53 | 51 | 36 | 89 | 25 |

| Wellington (Kelburn) | 415 | 158 | 97 | 2,010 | 0 | 54.3 | 68 | 51 | 55 | 42 | 79 | 34 |

| Nelson Airport | 6 | 125 | 74 | 2,410 | 44 | 53.2 | 71 | 53 | 54 | 34 | 82 | 23 |

| Blenheim | 14 | 108 | 59 | 2,430 | 33 | 54.5 | 74 | 55 | 52 | 36 | 89 | 23 |

| Hanmer | 1,270 | 143 | 89 | 1,910 | 88 | 49.6 | 73 | 48 | 48 | 28 | 89 | 15 |

| Hokitika | 12 | 194 | 140 | 1,860 | 19 | 51.6 | 66 | 53 | 51 | 36 | 76 | 27 |

| Lake Coleridge | 1,195 | 118 | 71 | .. | 69 | 50.0 | 71 | 48 | 49 | 30 | 88 | 18 |

| Christchurch | 22 | 116 | 59 | 1,990 | 37 | 52.6 | 70 | 50 | 53 | 34 | 90 | 25 |

| Timaru | 56 | 112 | 57 | 1,910 | 39 | 51.9 | 70 | 50 | 51 | 33 | 90 | 24 |

| Milford Sound | 16 | 193 | 163 | .. | 31 | 50.4 | 65 | 49 | 50 | 34 | 77 | 27 |