Table of Contents

The 1929 issue of the “New Zealand Official Year-book” represents the thirty-seventh number of the volume, and the eighth of the present royal-octavo series, the introduction of which in 1921 synchronized with a definite forward policy in the activities of the Census and Statistics Office and in the presentation of its publications.

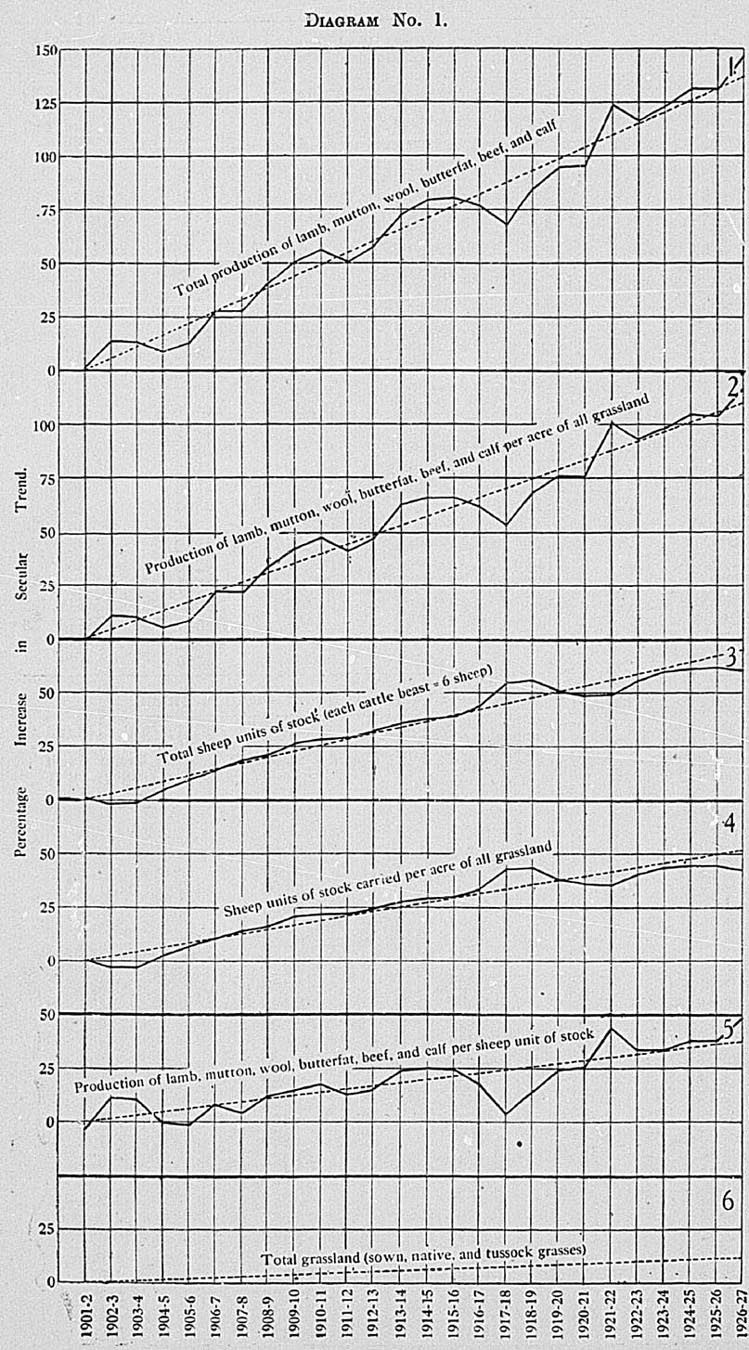

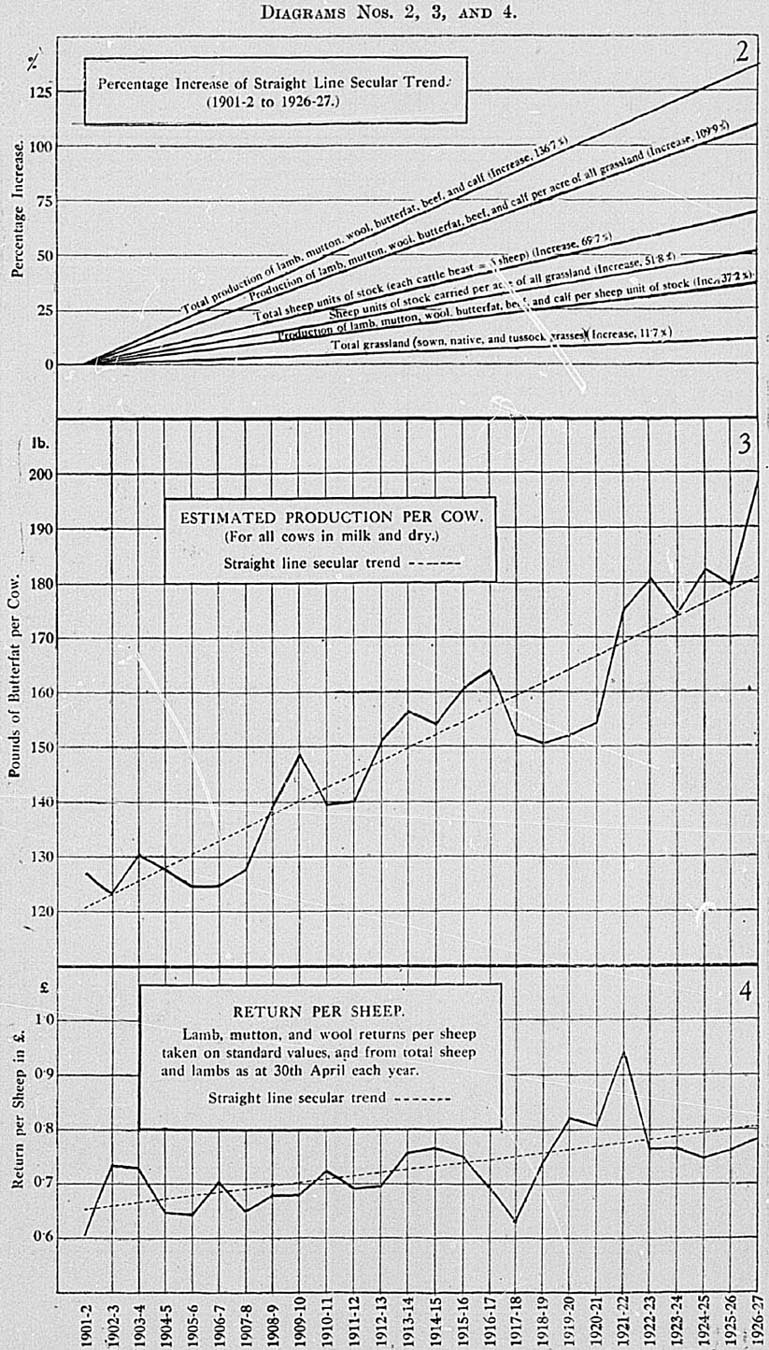

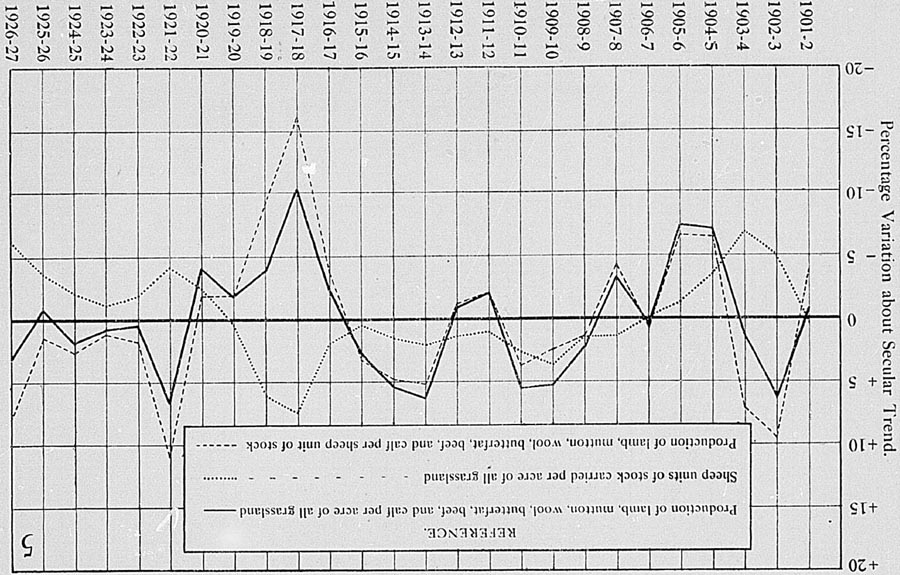

The present number is on the same lines as its immediate predecessors. No new sections have been added on this occasion, but considerable additions have been made to existing sections, and a special article has been included. The latter, by Messrs. E. J. Fawcett, M.A., and W. N. Paton, of the Department of Agriculture, contains informative results of a statistical investigation by a special method into the question of live-stock production, and is well illustrated by diagrams.

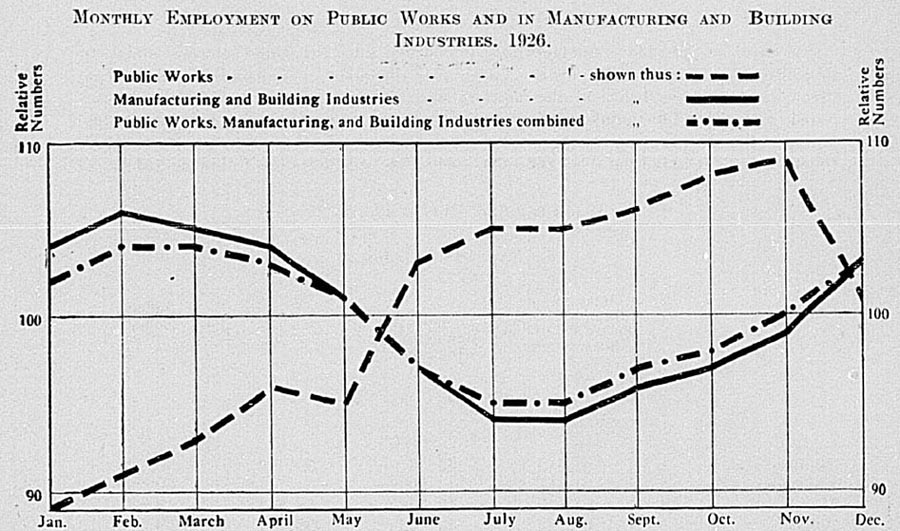

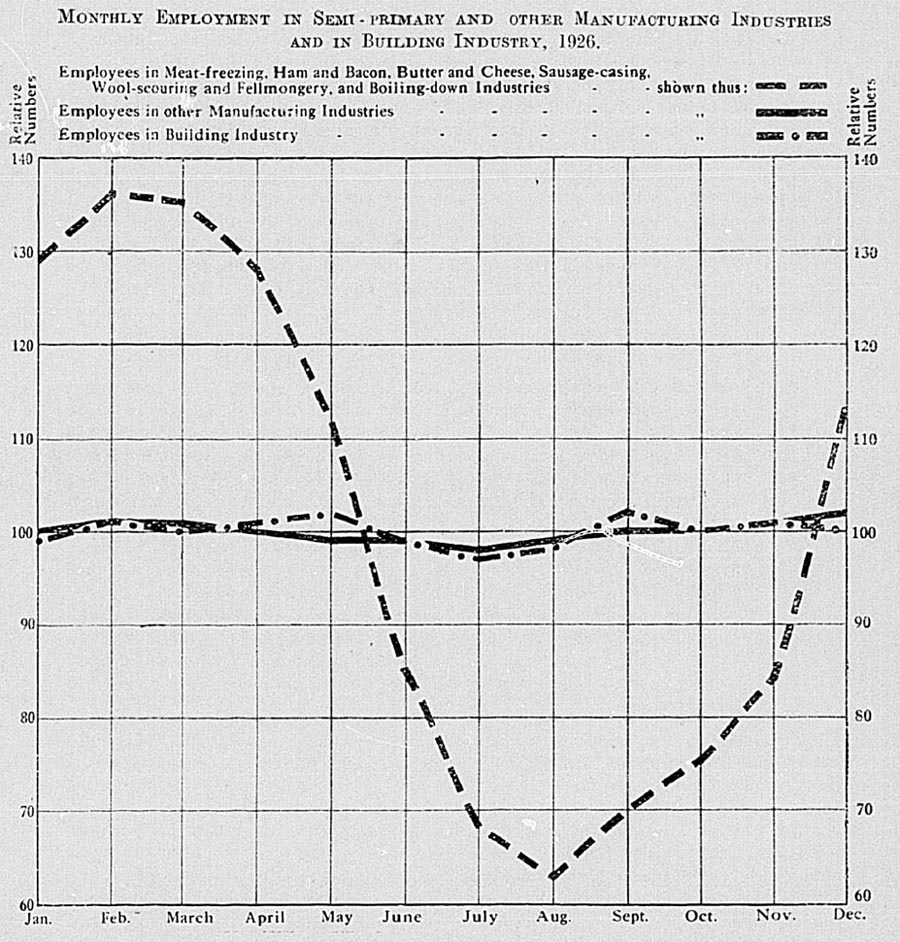

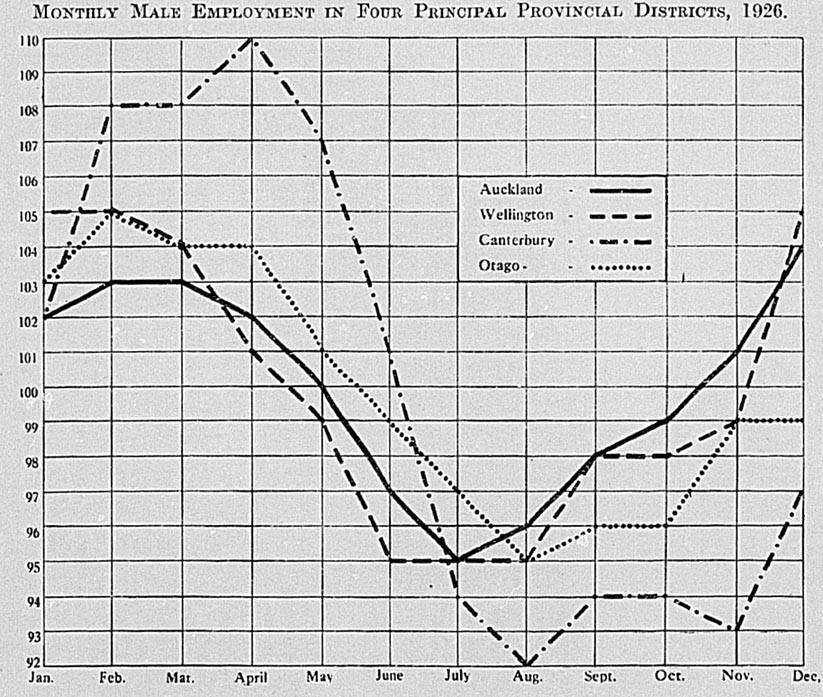

Among new matter added to existing sections, reference may be made to the results of a collection of statistics of motor-transport, which are given in Section XV—Roads and Road Transport; to the articles included in Section XXII—Factory Production, wherein industries are dissected according to their organization and nature, and the salient features compared; to the summarized figures of accounts relating to land-settlement and trading undertakings, which help to round off Subsection A of Section XXIV—Public Finance; to the piece on main-highways taxation given in Subsection B of the same section; and to the article on the monthly course of employment which appears in Section XL—Employment and Unemployment.

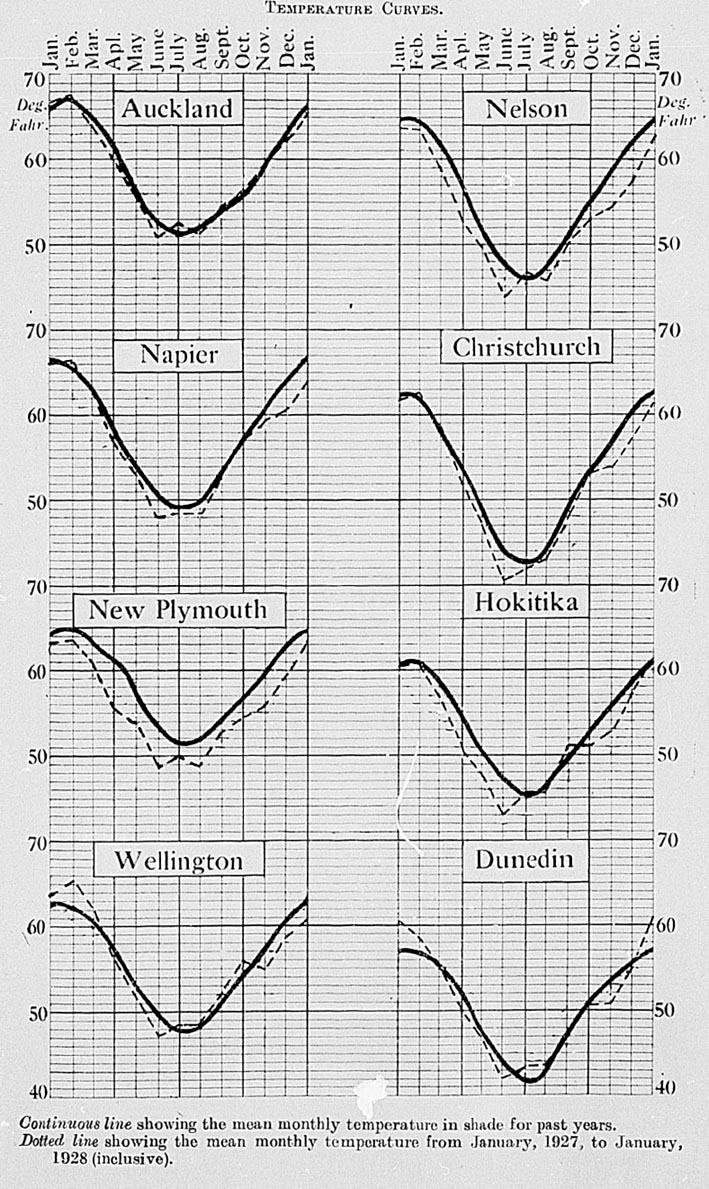

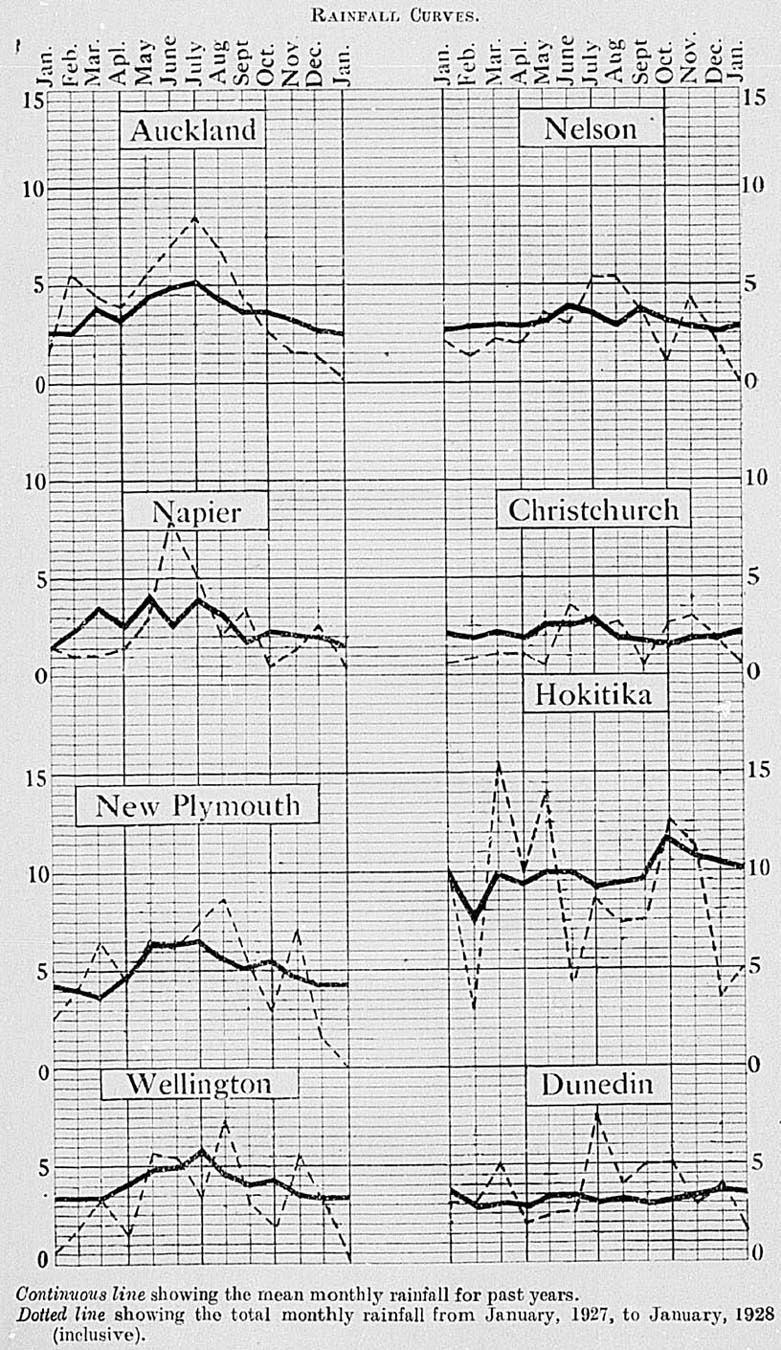

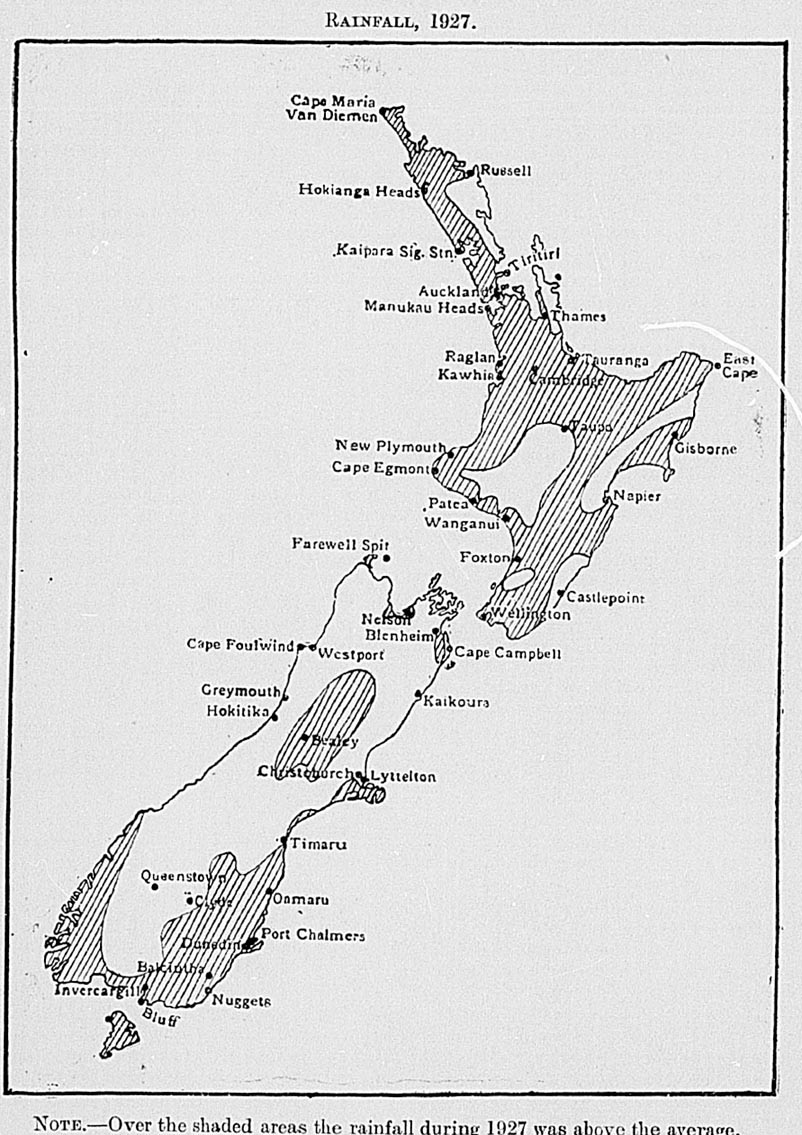

The article on Climate in Section I has been entirely rewritten by Dr. E. Kidson, M.A., D.Sc, Director of Meteorological Services, and the subsection devoted to Agricultural Production has also been rewritten. An appendix contains some of the results of the Population Census of 1926.

Attention is drawn to Section XLVI, containing a statistical summary covering the last fifty years. The presence of this summary is apparently overlooked by many users of the Year-book.

The list of successful candidates at the recent general election is given on page 936. Members of the new Ministry, with their portfolios, are shown overleaf.

MALCOLM

FRASER,

Government

Statistician.

Census and Statistics Office,

Wellington,

15th December, 1928.

Right Hon. Sir J. G. Ward, Bart., P.O., K.C.M.G., Prime Minister, Minister of Finance, Minister of Stamp Duties, Minister of External Affairs, Minister in Charge of Public Trust, Legislative, State Advances, Land and Income Tax, and High Commissioner's Departments.

Hon. G. W. FORBES, Minister of Lands, Minister of Agriculture, Minister in Charge of Land for Settlements, Scenery Preservation, Discharged Soldiers Settlement, and Valuation Departments.

Hon. T. M. Wilford, Minister of Justice, Minister of Defence, Minister in Charge of Police, Prisons, and War Pensions Departments.

Hon. Sir A. T. NGATA, Kt., Minister of Native Affairs, Minister of Cook Islands, Minister in Charge of Native Trust, Government Life Insurance, and State Fire and Accident Insurance Departments.

Hon. H. ATMORE, Minister of Education, Minister in Charge of Scientific and Industrial Research Department.

Hon. W. A. VEITCH, Minister of Labour, Minister of Mines, Minister in Charge of Pensions and Electoral Departments.

Hon. E. A. RANSOM, Minister of Public Works, Minister in Charge of Roads and Public Buildings.

Hon. W. B. TAVERNER, Minister of Railways, Minister of Customs, Commissioner of State Forests, Minister in Charge of Publicity and Advertising Departments.

Hon. J. B. DONALD, Postmaster-General, Minister of Telegraphs, Minister in Charge of Public Service Superannuation, Friendly Societies, and National Provident Fund Departments.

Hon. P. A. DE LA PERRELLE, Minister of Internal Affairs, Minister in Charge of Registrar-General's, Census and Statistics, Laboratory, Printing and Stationery, Audit, and Museum Departments.

Hon. J. G. COBBE, Minister of Marine, Minister of Industries and Commerce, Minister of Immigration, Minister in Charge of Inspection of Machinery Department.

Hon. A. J. STALLWORTHY, Minister of Health, Minister in Charge of Mental Hospitals Department.

Hon. T. K. SIDEY, Attorney-General, Leader of the Legislative Council.

Table of Contents

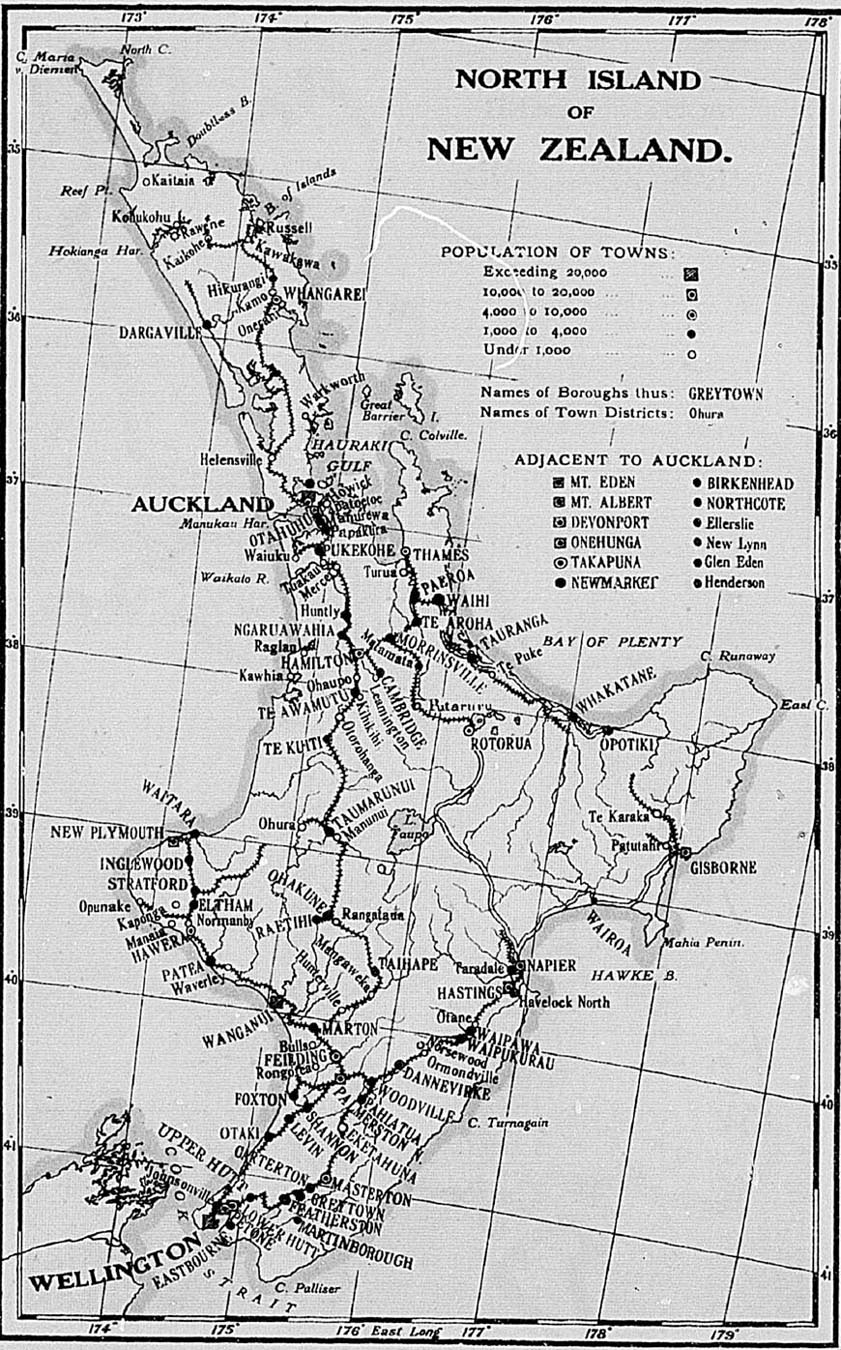

THE Dominion of New Zealand consists of two large and several small islands in the South Pacific. These may be classified as follows:—

Islands forming the Dominion proper, for statistical and general practical purposes:—

North Island and adjacent islets. South Island and adjacent islets. Stewart Island and adjacent islets. Chatham Islands. Outlying islands included within the geographical boundaries of New Zealand as proclaimed in 1847:—

Three Kings Islands. Antipodes Islands. Auckland Islands. Bounty Islands. Campbell Island. Snares Islands. Islands annexed to New Zealand:—

Kormadec Islands. Manahiki Island. Cook Islands. Rakaanga Island. Niue (or Savage) Island. Pukapuka (or Danger) Island. Palmerston Island. Nassau Island. Penrhyn (or Tongareva) Island. Suwarrow Island.

The Proclamation of British sovereignty over New Zealand, dated the 30th January, 1840, gave as the boundaries of what was then the colony the following degrees of latitude and longitude: On the north, 34° 30' S. lat.; on the south, 47° 10' S. lat.; on the east, 179° 0' E. long.; on the west, 166° 5' E. long. These limits excluded small portions of the extreme north of the North Island and of the extreme south of Stewart Island.

In April, 1842, by Royal Letters Patent, and again by the Imperial Act 26 and 27 Vict., c. 23 (1863), the boundaries were altered so as to extend from 33° to 53° of south latitude and from 162° of cast longitude to 173° of west longitude. By Proclamation bearing date the 21st July, 1887, the Kermadec Islands, lying between the 29th and 32nd degrees of south latitude and the 177th and 180th degrees of west longitude, were declared to be annexed to and to become part of the then Colony of New Zealand.

By Proclamation of the 10th June, 1901, the Cook Group of islands, and all the other islands and territories situate within the boundary-lines mentioned in the following schedule, were included as from the 11th June, 1901:—

A line commencing at a point at the intersection of the 23rd degree of south latitude and the 156th degree of longitude west of Greenwich, and proceeding due north to the point of intersection of the 8th degree of south latitude and the 156th degree of longitude west of Greenwich; thence due west to the point of intersection of the 8th degree of south latitude and the 167th degree of longitude west of Greenwich; thence due south to the point of intersection of the 17th degree of south latitude and the 167th degree of longitude west of Greenwich; thence due west to the point of intersection of the 17th degree of south latitude and the 170th degree of longitude west of Greenwich; thence due south to the point of intersection of the 23rd degree of south latitude and the 170th degree of longitude west of Greenwich; and thence due east to the point of intersection of the 23rd degree of south latitude and the 156th degree of longitude west of Greenwich.

By mandate of the League of Nations the New Zealand Government also now administers the former German possession of Western Samoa; and, jointly with the Imperial Government and the Government of Australia, holds the League's mandate over the Island of Nauru.

By Imperial Order in Council of the 30th July, 1923, the coasts of the Ross Sea, with the adjacent islands and territories, were declared a British settlement within the meaning of the British Settlements Act, 1887, and named the Ross Dependency. The Governor-General of New Zealand is Governor of the Ross Dependency, and is vested with the administration of the dependency.

By Imperial Orders in Council of the 4th November, 1925, the Union or Tokelau Islands (consisting of the islands of Fakaofu, Nukunono, and Atafu, and the small islands, islets, rocks, and reefs depending on them) were excluded from the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony, and placed under the administration of the Governor-General of New Zealand. In accordance with a provision of the second of these Orders in Council, the Governor-General's authority and powers in connection with the administration of the islands were, by New Zealand Order in Council of the 8th March, 1926, delegated to the Administrator of Western Samoa.

The total area of the Dominion of New Zealand, which does not include the territories administered under mandate, the Ross Dependency, and the Tokelau Islands, is 103,862 square miles. The areas of the principal islands are as follows:—

| Square Miles. | |

| North Island and adjacent islets | 44,131 |

| South Island and adjacent islets | 58,120 |

| Stewart Island and adjacent islets | 662 |

| Chatham Islands | 372 |

| Total Dominion proper | 103,285 |

| “Outlying” islands | 284 |

| “Annexed” islands | 293 |

| Grand total | 103,862 |

The mountainous character of New Zealand is one of its most striking physical characteristics. In the North Island mountains occupy approximately one-tenth of the surface; but, with the exception of the four volcanic peaks of Egmont (8,260 ft.), Ruapehu (9,175 ft.), Ngauruhoe (7,515 ft.), and Tongariro (6,458 ft.), they do not exceed an altitude of 6,000 ft. Of these four volcanoes only the first-named can be classed as extinct. Other dormant volcanoes include Mount Tarawera and White Island, both of which have, in recent years, erupted with disastrous consequences. Closely connected with the volcanic system are the multitudinous hot springs and geysers.

The South Island contains much more mountainous country than is to be found in the North. Along almost its entire length runs the mighty chain known as the Southern Alps, rising to its culmination in Mount Cook (12,349 ft.). No fewer than sixteen peaks of the Southern Alps attain a height of over 10,000 ft. Owing to the snow-line being low in New Zealand, many large and beautiful glaciers exist. The Tasman Glacier (Southern Alps), which has a total length of over eighteen miles and an average width of one mile and a quarter, is the largest. On the west coast the terminal face of the Franz Josef Glacier is but a few hundred feet above sea level.

The following list of named peaks over 7,000 ft. in height has been compiled from various sources. It does not purport to cover all such peaks, nor is exactitude claimed in respect of the elevations shown, many of which are known to be only approximate.

| Mountain or Peak. | Height (Feet). |

|---|---|

| *Not available. | |

| North Island— | |

| Ruapehu | 9,175 |

| Egmont | 8,260 |

| Ngauruhoe | 7,515 |

| Kaikoura Ranges— | |

| Tapuaenuku | 9,460 |

| Kaitarau | 8,700 |

| Mitre Peak | 8,532 |

| Whakari | 8,500 |

| St. Bernard | 7,416 |

| Dillon | 7,132 |

| St. Arnaud Range— | |

| Travers | 7,666 |

| Spenser Range— | |

| Franklyn | 7,671 |

| Una | 7,540 |

| Ella | 7,438 |

| Faerie Queen | 7,332 |

| Paske | 7,260 |

| Humboldt | 7,240 |

| Dora | 7,100 |

| Southern Alps— | |

| Cook | 12,349 |

| Tasman | 11,475 |

| Dampier | 11,287 |

| Silberhorn | 10,757 |

| Lendenfeldt | 10,450 |

| David's Dome | 10,443 |

| Malte Brun | 10,421 |

| Teichelmann | 10,370 |

| Sefton | 10,354 |

| Haast | 10,294 |

| Elie de Beaumont | 10,200 |

| Douglas Peak | 10,107 |

| La Perouse | 10,101 |

| Haidinger | 10,059 |

| De la Beche | 10,058 |

| The Minarets | 10,058 |

| Aspiring | 9,975 |

| Hamilton | 9,915 |

| Glacier Peak | 9,865 |

| Grey Peak | 9,800 |

| Aiguilles Rouges | 9,731 |

| Nazomi | 9,716 |

| Darwin | 9,715 |

| Chudleigh | 9,686 |

| Annan | 9,667 |

| Low | 9,653 |

| Haeckel | 9,649 |

| Goldsmith | 9,532 |

| Conway Peak | 9,519 |

| Walter | 9,507 |

| Green | 9,305 |

| D'Archiac | 9,279 |

| Hochstetter Dome | 9,258 |

| Earnslaw | 9,250 |

| Hutton | 9,200 |

| Nathan | 9,200 |

| Sibbald | 9,180 |

| Arrowsmith | 9,171 |

| Bristol Top | 9,167 |

| Spencer | 9,167 |

| The Footstool | 9,073 |

| Rudolf | 9,039 |

| The Dwarf | 9,025 |

| Burns | 8,984 |

| Nun's Veil | 8,975 |

| Bell Peak | 8,950 |

| Johnson | 8,858 |

| Aylmer | 8,819 |

| Hopkins | 8,790 |

| Brodrick | 8,777 |

| Priest's Cap | 8,761 |

| Halcombe | 8,743 |

| Aurora Peak | 8,733 |

| Meeson | 8,704 |

| Meteor Peak | 8,701 |

| Mannering | 8,700 |

| Ward | 8,681 |

| Brunner | 8,678 |

| Jervois | 8,675 |

| Couloir Peak | 8,675 |

| Whitcombe | 8,656 |

| Sealy | 8,651 |

| Moffatt | 8,647 |

| Thomson | 8,646 |

| Hooker | 8,644 |

| Vampire Peak | 8,600 |

| Aigrette Peak | 8,594 |

| Dilemma Peak | 8,592 |

| Evans | 8,580 |

| Bismarck | 8,575 |

| Glenmary | 8,524 |

| Isabel | 8,518 |

| Dechen | 8,500 |

| Loughnan | 8,495 |

| Pibrae | 8,472 |

| Wolseley | 8,438 |

| Unicorn Peak | 8,394 |

| Forbes | 8,385 |

| Anderegg | 8,360 |

| Strachan | 8,359 |

| Beatrice | 8,350 |

| Jackson | 8,349 |

| Maunga Ma | 8,335 |

| Livingstone | 8,334 |

| Baker Peak | 8,330 |

| Bannie | 8,300 |

| Eagle Peak | 8,300 |

| Conrad | 8,300 |

| Richmond | 8,300 |

| Acland | 8,294 |

| Jukes | 8,289 |

| Darby | 8,287 |

| Centaur | 8,284 |

| Tyndall | 8,282 |

| Macfarlane | 8,278 |

| Victoire | 8,269 |

| Alba | 8,268 |

| Coronet Peak | 8,265 |

| Percy Smith | 8,254 |

| Williams | 8,249 |

| Roberts | 8,239 |

| Malcolm Peak | 8,236 |

| Cumine | 8,223 |

| Huxley | 8,201 |

| Kim | 8,200 |

| Spence | 8,200 |

| Eric | 8,200 |

| Drummond | 8,197 |

| McClure | 8,192 |

| Blair Peak | 8,185 |

| Huss | 8,165 |

| Louper Peak | 8,165 |

| The Anthill | 8,160 |

| Ansted | 8,17 |

| Dennistoun | 8,150 |

| Dun Fiunary | 8,147 |

| Tyndall | 8,116 |

| Fettes | 8,092 |

| Trent | 8,076 |

| King | 8,064 |

| Glacier Dome | 8,047 |

| McKerrow | 8,047 |

| Humphries | 8,028 |

| Lucia | 8,015 |

| Graceful Peak | 8,000 |

| Lean Peak | 8,000 |

| Raureka Peak | 8,000 |

| Fletcher | 7,995 |

| Farrar | 7,982 |

| Radove | 7,914 |

| Cooper | 7,897 |

| Ramsay | 7,880 |

| Frances | 7,876 |

| Cloudy Peak | 7,870 |

| Observation Peak | 7,862 |

| Cadogan Peak | 7,850 |

| Blackburn | 7,835 |

| Strauchon | 7,815 |

| Du Faur Peak | 7,800 |

| Turret Peak | 7,800 |

| Dobson | 7,799 |

| Westland | 7,762 |

| Dark | 7,753 |

| Hulka | 7,721 |

| Copland | 7,695 |

| Park Dome | 7,688 |

| Turner's Peak | 7,679 |

| Edison | 7,669 |

| Petermann | 7,664 |

| Montgomery | 7,661 |

| St. Mary | 7,656 |

| Fraser | 7,654 |

| Taylor | 7,641 |

| Sibyl Peak | 7,625 |

| Edith Peak | 7,600 |

| Madonna Peak | 7,600 |

| McKenzie | 7,563 |

| Onslow | 7,561 |

| Novara Peak | 7,542 |

| Proud Peak | 7,540 |

| Nicholson | 7,500 |

| Pyramus | 7,500 |

| Howitt | 7,490 |

| Erebus | 7,488 |

| Eros | 7,452 |

| Rolleston | 7,447 |

| Turnbull | 7,400 |

| Annette | 7,351 |

| Neave | 7,350 |

| Roon | 7,344 |

| Maitland | 7,291 |

| Adams | 7,247 |

| Jollie | 7,232 |

| Enys | 7,202 |

| Potts | 7,197 |

| German | 7,184 |

| Hutt | 7,180 |

| Kinkel | 7,121 |

| Marshimn | 7,116 |

| Murray | 7,065 |

| Artist Dome | 7,061 |

| Melettrict Peak | 7,061 |

| Beaumont | 7,035 |

| Ballance | 08 |

| Burnett | 7,003 |

| Two Thumbs Rage— | |

| Thumbs | 8,338 |

| Alma | 8,204 |

| Fox | 7,604 |

| Musgrave | 7,379 |

| Chevalier | 7,339 |

| Sinclair | 7,022 |

| Darran Range— | |

| Tutoko | 9,691 |

| Madeline | 9,042 |

| Christina | 8,675 |

| Milne | 8,000 |

| Barrier Range— | |

| Edward | 8,459 |

| Pollux | 8,341 |

| Brewster | 8,264 |

| Castor | 8,256 |

| Liverpool | 8,040 |

| Islington | 7,700 |

| Goethe | 7,680 |

| Cosmos | 7,640 |

| Oblong Peak | 7,600 |

| Somnus | 7,599 |

| Joffre | 7,500 |

| French | 7,400 |

| Head | 7,400 |

| Moira | 7,300 |

| Clarke | 7,300 |

| Plunket | 7,220 |

| Ark | 7,190 |

| Balloon | * |

| The Remarkables— | |

| Double Cone | 7,688 |

| Ben Nevis | 7,650 |

The hot springs of the North Island form one of the most remarkable features of New Zealand. They are found over a large area, extending from Tongariro, south of Lake Taupo, to Ohaeawai, in the extreme north—a distance of some three hundred miles; but the principal seat of hydrothermal action appears to be in the neighbourhood of Lake Rotorua, about forty miles north-north-east from Lake Taupo. By the destruction of the famed Pink and White Terraces at Lake Rotomahana during the eruption of Mount Tarawera on the 10th June, 1886, the neighbourhood was deprived of attractions unique in character and of unrivalled beauty; but the natural features of the country—the numerous lakes, geysers, and hot springs, some of which possess remarkable curative properties in certain complaints—are still very attractive to tourists and invalids. The importance of conserving this region as a sanatorium for all time has been recognized by the Government, and it is dedicated by Act of Parliament to that purpose.

There are also several small hot springs in the South Island, the best-known being those at Hanmer.

The following article on the mineral waters and spas of New Zealand is by the Government Balneologist, Dr. J. D. C. Duncan, M.B., Ch.B. (Edin.), Member of the International Society of Medical Hydrology, Fellow of the Royal Society of Medicine, and Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society:-

It has been acknowledged by the leading hydrologists in Europe that New Zealand possesses the most valuable mineral waters in existence. Not only are these mineral waters interesting from a tourist's point of view, but they are, because of their medicinal value, of great therapeutic importance, and, as a Dominion asset, worthy of the deepest scientific consideration.

From the spectacular aspect only a brief mention need be made in this article, as a full description of springs, geysers, and mud-pools has been given in Dr. Herbert's book, “The Hot Springs of New Zealand”—a book that presents a comprehensive and vivid picture of the main manifestations of thermal activity in New Zealand.

Dealing with the medical-scientific aspect of the mineral waters, the space of this article will permit only the shortest account of the treatments; and, as the Rotorua Spa is of premier importance, the article will be confined almost entirely to its operations.

Since and as the result of experience gained during the war the subject of hydrotherapy has been recreated on modern scientific lines, and the actions of thermal mineral waters have been investigated, both chemically and physiologically, in determining their therapeutic value in the treatment of disease.

The mineral waters which have been harnessed for therapeutic use at the Rotorua Spa are of two main varieties—viz., the “Rachel,” which is an alkaline, sulphuretted water, emollient to the skin, and sedative in reaction; and the “Priest,” or free-acid water, which, due to the presence of free sulphuric acid, is mainly stimulating and tonic in reaction. There is, in addition to the foregoing, a valuable silicious mud similar to that found in Pistany, in Czecho-Slovakia, which, in its own sphere in hydrotherapy, exerts its influence as a curative agent.

However, it is in the “Priest” waters that one finds one's most valuable ally in the treatment of arthritis, fibrositis (the so-called rheumatic affections), and cases of nervous debility. The “Rachel” and mud baths are used mostly in those cases of fibrositis where the condition requires a softening effect; and in the types where pain is a manifest symptom these baths are invaluable as soothing and sedative agents.

In these natural acid baths the reactions are mainly stimulating, with increased hyperæmia in the parts submerged, and marked lessening of pain and swelling in the affected joints and tissues. Those waters containing free carbonic-acid gas are used for the cases of fibrositis in which the circulation requires the stimulating action of gaseous baths.

The “New Priest” waters, containing approximately 16-80 grains per gallon of free sulphuric acid, are utilized in the form of open pools, deep step-down baths, and slipper baths. They are prescribed at a suitable temperature for the individual case.

The “Old Priest” waters, containing a much lower degree of free acid (3-77 grains to the gallon), and of varying temperatures (from 84° F. to 102° F.), are used for treatment at their source. The waters, percolating through their pumice - bed, are confined in pools, and contain free carbonic-acid gas bubbling through the water.

The very strong “Postmaster” waters are also confined within pools on the natural pumice - bed, and, by a primitive arrangement of wooden sluice-valves, maintained at three ranges of temperature—viz., 104°, 106°, and 108° F. They contain 22-29 grains of free sulphuric acid to the gallon, and are strongly counter-irritant in their reactions.

In such a brief account as this one can only deal in generalizations, and the forms of treatment mentioned must necessarily be subject to wide variations. In any form of hydro-therapeutic treatment the regime must be adapted to the individual manifestations of the disease, and no routine rules or regulations can be laid down in spa operations.

The “New Priest” waters are, for the most part, prescribed for patients suffering from subacute or chronic fibrositis, subacute or chronic gout, and the various forms of arthritis. Except in cases of marked debility, those patients are given graduated baths, at temperatures ranging from 102° to 104° F., from ten to fifteen minutes daily. Most of the baths are fitted with a subaqueous douche having a pressure of 25 lb., which is directed under water on the affected tissues. The bath is usually followed by a light or hot pack, according to the needs of the case.

The subthermal “Old Priest” waters (temperature 84° F.), containing a high degree of free carbonic-acid gas, are particularly valuable in the treatment of functional nervous disease, and the methods of administration are similar to those obtaining at Nauheim. The reactions are markedly stimulating through the sympathetic nervous system, and bring about, by reflex action, a tonic effect on the heart.

The “Postmaster” baths are used in the treatment of the more chronic forms of fibrositis, arthritis deformans, and gout, requiring a more or less heroic type of procedure. They are usually prescribed in combination—i.e., a certain time in each pool, commencing with the lowest temperature. The hyperæmic reaction is most marked, and in many of the cases where pain is a predominant symptom there is a temporary paralysis of the surface nerves, as well as a strong reflex excitation of the heart. For this reason these baths are not given to patients suffering from cardiac weakness.

The mud baths being highly impregnated with silica, which has a bland, sedative effect on the tissues, are particularly indicated in cases of acute or sub-acute neuritis, gout, and certain skin conditions. The action of these baths is to induce an active hyperæmia in the patient with an actual absorption of free sulphur, which is present in considerable quantity. Also, the radio-activity of this medium (0.185 per c.c.) is possibly an active factor in the therapeutic action of these baths. In some of the cases undergoing mud-bath treatment the effect has been almost miraculous—instant relief from pain; reduction of swelling caused by inflammatory exudates—and such patients have been able to discard crutches or other adventitious aids and walk with more or less normal comfort.

Perhaps, of more recent date, the most efficacious effects of mud treatments have been manifested in cases of skin conditions—notably psoriasis: cases which have resisted all forms of drug treatment have cleared up in an almost magical manner; and so frequently have such cures been effected that one believes that the silicious mud of Rotorua has some markedly specific action as a therapeutic agent.

The treatment of gout depends entirely on the individual manifestations. In certain subacute and chronic types fairly high temperatures (104° to 106° F., with hot packs) of “Priest” water are employed, in order to hasten the absorption of exudates and the elimination of uric acid. In acute cases of acute gout more sedative measures are pursued, such as “Rachel” baths at neutral temperatures, local mud packs, and rest. As soon as the conditions permit, these patients are changed over to acid water baths. Cases of chronic gout exhibiting metabolic stagnation sometimes receive considerable benefit from the counter-irritant effects of the strongly acid “Postmaster” waters.

Separate establishments, containing the most modern apparatus of sprays, douches, hot steam, &c., are available for wet massage and treatments of the Aix-Vichy type.

The massage-rooms are fitted with the latest installations of electrical equipment—Bristowe tables, diathermy, high frequency, Bergonie chair, X-ray, Schnée baths, Greville hot air, and other apparatus for carrying out the most up-to-date methods of electrical-therapeutic treatments.

The baths are administered by a trained staff of attendants, and the massage, electrical-therapy, and douches carried out by a qualified staff of operators.

In every respect the hydrotherapy treatments aim at a restoration of function, and the measures employed are, for the most part, re-educative.

In connection with the Rotorua Spa is a sanatorium of seventy beds, where patients whose finances are restricted can receive treatment at an exceedingly moderate cost. The institution consists of cubicles and open wards. Thermal baths and massage-rooms in the building provide for the more helpless type of invalid.

From Sixty thousand to eighty thousand baths are given annually, and about thirty thousand special treatments—massage, electrical therapy, &c.—are administered each year at the Rotorua Spa.

The usual course of treatment lasts from four to six weeks, and the high percentage of cures and improvements testifies to the value of the thermal mineral waters and the hydro-therapeutic treatments obtaining in this Dominion.

The following account of the rivers of New Zealand has been written by Professor R. Speight, M.Sc., F.G.S., Curator of the Canterbury Museum:—

In a country like New Zealand, with marked variations in topographic relief and with a plentiful and well-distributed rainfall, the rivers must necessarily form characteristic features of the landscape. Mountains, however, exert an important influence on their adaptability to the necessities of commerce, reducing their value on the one hand while increasing it on the other. Owing to the steep grades of their channels few of the rivers are fitted for navigation except near their months, but to compensate for this disability they furnish in many places ideal sites for power plants, which will in all probability be so utilized in the near future that New Zealand may become the manufacturing centre of the Southern Hemisphere. No country south of the Equator, except Chile and Patagonia, possesses such stores of energy conveniently placed, which cannot become exhausted until the sun fails to raise vapour from the neighbouring seas—a contingency to be realized only when life on the earth is becoming extinct.

The only part of the country which possesses rivers capable of being used for navigation is the North Island. The relief is not so marked as in the South, and many streams flow in deep beds, with somewhat sluggish current. There are flowing into the Tasman Sea rivers like the Waikato, Wairoa, Mokau, and Wanganui, which served the Maoris as important means of communication, and which are decidedly useful for the purposes of modern transport. The first-mentioned of these is by far the most important. Rising in the snows of Ruapehu, and receiving numerous affluents from the western slopes of the Kaimanawa Range, it pursues a northerly course for twenty miles with all the features of a mountain torrent till it enters Lake Taupo. Almost immediately on leaving this it plunges over the Huka Falls, formed by a hard ledge of volcanic rock, and then runs first north-east and then north-west till it reaches the sea, the amount of water discharged exceeding 800,000 cubic feet per minute. In certain parts of its course the valley is gorge-like in character and picturesque rapids obstruct its navigation, but in its lower reaches it widens out and flows for long distances through marshes and shallow lakes, and empties into the sea by a wide estuary, which is unfortunately blocked by a bad bar. It receives on the west a large tributary, the Waipa—itself also navigable for small steamers, and a river which may ultimately play no small part in the development of the south-western portion of the Auckland Province.

The Northern Wairoa shows features which resemble those of the Waikato. It rises in the hilly land of the North Auckland Peninsula, and flows south as a noble stream till it enters Kaipara Harbour, a magnificent sheet of water with many winding and far-reaching arms, but with its utility greatly discounted by the presence of a bar which, though with sufficient depth of water for vessels of moderate size, is frequently impracticable. The total estimated discharge from the streams running into the Kaipara Harbour is about 500,000 cubic feet per minute, of which the Wairoa certainly contributes one-half.

The Mokau River, which enters the sea about sixty miles north-east of New Plymouth, is navigable for a considerable distance in its lower reaches. Here it is flanked by limestone bluffs, clad with a wealth of ferns and other native vegetation, forming one of the most picturesque rivers of the county. Higher up, as in the Waikato, there are fine falls, which may ultimately be used for power purposes owing to their proximity to one of the important agricultural districts of the North Island.

The last of the four principal navigable rivers on the west coast is the Wanganui. This river gathers its initial supplies from the western flanks of the volcanic ridge of the centre of the Island, from which numerous streams run west over the Waimarino Plain in somewhat open channels till they coalesce and form the main river. Other tributaries, such as the Tangarakau and the Maunganui-te-ao, subsequently add their quota, and the river then flows in a southerly direction in loops and windings depressed far below the level of the coastal plain, between high papa bluffs clad with rich vegetation, till it reaches the sea as a deep tidal stream, the amount of its discharge being estimated at over 500,000 cubic feet per minute. Through the greater part of its course it has a characteristic trench-like channel, with a fairly even gradient, and with only slight interruptions from rapids. At low water these are most troublesome, but at times of high river-level they are passed without serious difficulty. This fine stream affords communication into a country difficult of access by road or railway, and it may be taken as typical of other smaller streams to the west, such as the Waitotara, the Patea, and the Waitara, which are navigable to a less extent, principally owing to the obstructions of timber in their channels; while the rivers lying more to the east and with courses parallel to the Wanganui—e.g., the Rangitikei and the Wangaehu—are more rapid and have little adaptability to the needs of transport. Further east still, in the neighbourhood of the Ruahine Mountains, the rivers become true mountain torrents, with steep grades and rapid currents.

On the other coast of the North Island the only streams capable of being used for navigation except just at their mouths are those running into the Firth of Thames—the Piako and the Waihou. But no account of our navigable rivers would be complete without a reference to the “drowned rivers” which characterize the northern parts of the Island. The Kaipara may be taken as a typical case of such, for the harbour merely represents the depressed and sunken lower reaches of the Wairoa and other streams. A further notable case is the Hokianga River, which runs for twenty miles between wooded hills and receives numerous tributaries from them, tidal for a considerable part of their courses, and allowing water communication to be used for at least fifteen miles from the point where actual discharge into the open sea takes place.

The remaining rivers of the North Island of any importance rise in the mountain axis that stretches from near Wellington towards the eastern margin of the Bay of Plenty. Towards the southern end, where it lies close to the shore of Cook Strait, the rivers from it are short and swift, the only exception being the Manawatu, which has cut a deep gorge in the mountain barrier and drains an extensive basin lying on the eastern flanks of the Ruahine Range to the north, and of the Tararua Range to the south, as well as a considerable area of country on the slopes of the Puketoi Range, its headwaters in this direction reaching nearly to the east coast of the Island. The Manawatu has an estimated discharge of over 600,000 cubic feet per minute, and judging by this it must be considered the second-largest river in the North Island. Although the Manawatu is the only stream which has succeeded up to the present in cutting through the range at its head, several of the rivers flowing west have eaten their way far back, and in future ages will no doubt struggle with the Manawatu for the supremacy of that tract of land lying to the cast of the range. Remarkable changes are likely to occur in the direction of drainage, especially if the earth-movements now in progress in the neighbourhood of Cook Strait continue for any lengthy period.

The central and southern parts of the Tararua and Rimutaka Ranges are drained by the Ohau, Otaki, Waikanae, and other streams flowing into Cook Strait; by the Hutt River, which flows into Wellington Harbour; and by the Ruamahanga and its tributaries, flowing through the Wairarapa Plain. These last include within their basins some amount of papa-country as well as steep mountain-slopes. While in the former they run in deep narrow channels, but when free from it they spread at times over wide shingly beds in a manner more characteristic of the streams of the South Island.

Several large rivers rise in the Ruahine Mountains and their northerly extensions. The chief of these flowing into Hawke Bay are the Ngaururoro, Tukituki, Mohaka, and Wairoa, the first being noteworthy for the enormous amount of shingle it has brought down; while farther north the Waipaoa runs into Poverty Bay and the Waiapu into the open sea, both draining an extensive area of rich papa land. From the north-western side of the range the Whakatane and the Rangitaiki, two considerable streams, flow into the Bay of Plenty.

The chief factor which determines the characters of the rivers of the South Island is the great mountain mass of the Southern Alps, with its extensions and semi-detached fragments. Its general direction is parallel to the west coast of the Island, and nearer to this coast than to the eastern one; it also lies right athwart the path of the wet westerly winds which prevail in these latitudes. The moisture collected during their passage across the Tasman Sea is precipitated in the form of rain on the coastal plain and the hills behind it, while the mountain-tops intercept it chiefly in the form of snow, the amount of annual rainfall varying from about 100 in. at sea-level up to over 200 in. near the main divide. The eastern slopes of the range receive less rain, and are increasingly drier as the coast is approached, but there the amount is slightly augmented by moist winds coming from the open ocean to the east. In the higher mountain valleys on both sides of the range lie numerous glaciers, either of the small cliff type or large ones of the first order, the most notable being the Tasman, Hooker, Mueller, Godley, Rangitata, Lyell, and Ramsay on the east, and the Franz Josef and Fox on the west. The chief large rivers of the central district of the Island rise from the terminals of the glaciers and issue from the ice as streams of considerable volume. They reach their highest level in spring and summer, for not only does the heavier rainfall of that time of the year serve to swell them inordinately, but the snow and ice are melted under the combined influence of the rain itself and of the strong sun-heat. Although they are almost always more or less turbulent and dangerous to the traveller who attempts to ford them—in the warm months of the year they are liable to sudden and serious floods, and formerly they frequently blocked communication for weeks at a stretch—now, however, many of the worst streams have been bridged, and communication is thus easier and less precarious.

The general form of these valleys is of a fairly uniform type. Their heads are usually amphitheatre-like in shape, and for some distance they are occasionally covered by old moraines, and the course of the stream is impeded by huge angular blocks washed out of these or shed from the steep slopes; at times, too, the rivers flow through deep and somewhat narrow gorges. Lower down the valleys open out, with even steep sides, nearly perpendicular at times, and with flat floors covered by a waste of shingle, over which the rivers wander in braided streams. The sides are clad with dense bush for a height of approximately 2,500 ft., that merges into a tangle of subalpine scrub, to be succeeded after another 1.000 ft. by open alpine meadow, gradually passing upward into bare rock and perpetual snow.

After leaving the mountains the streams flowing to the West Coast cross the narrow fringe of aggraded coastal plain, and cut down their channels through old glacial drifts which furnished in former times rich leads of alluvial gold. The mouths of these rivers are usually blocked by shallow bars, but after heavy floods a channel may be scoured out, only to be closed, when the river falls, by the vast quantities of drift material moved along the beach by the heavy seas and the strong shore currents which sweep the open coast. It is only where it is possible to confine the river-mouths and direct their scour that open channels can be permanently maintained, and even these entrances are at times extremely dangerous to shipping.

The chief rivers which flow from the central portion of the Southern Alps to the Tasman Sea are the Taramakau, Hokitika, Wanganui, Wataroa, Waihao, Karangarua, Haast, and Arawata. All rise in glaciers, and their valleys are remarkable for their magnificently diversified bush and mountain scenery. Occasionally lakes, ponded back behind old moraines or lying in rock-bound basins and fringed with primeval forest, lend charm to the landscape, and make a journey along the Westland Plain one of the most delightful in New Zealand from the scenic point of view.

Farther north glaciers are absent, but the heavy rain feeds numerous large streams and rivers, the most notable being the Grey and the Buller, the latter being in all probability the largest on the west coast, the amount of its discharge being estimated at nearly 1,000,000 cubic feet per minute.

The general features of the rivers which flow into the West Coast Sounds are somewhat similar, except that few rise in glaciers, and there is no fringe of plain to the mountains. The valleys have steeper sides, waterfalls and lakes are more common, and are ideally situated for power installations. One of the large rivers of this area is the Hollyford, which flows into Martin's Bay; but the largest of all is the Waiau, which drains the eastern side of the Sounds region, receives the waters of Lakes Te Anau, Manapouri, and Monowai, and enters the sea on the south coast of the Island.

The rivers on the eastern slope of the Alps present features similar to those of the west coast in their upper courses, but the valleys are broader and flatter, floored from wall to wall with shingle and frequently containing large lakes of glacial origin. In those cases where lakes do not now exist there are undoubted signs that they occurred formerly, having been emptied by the erosion of the rock-bars across their lower extremities and filled at the same time by detrital matter poured in at their heads.

The largest of all these rivers is the Clutha; in fact, it discharges the greatest volume of water of any river in New Zealand, the amount being estimated at over 2,000,000 cubic feet per minute. The main streams which give rise to this river flow into Lakes Wanaka and Hawea, and have their sources in the main divide to the north of the ice-clad peak of Mount Aspiring and in the neighbourhood of the Haast Pass. After flowing as a united stream for nearly thirty miles it receives from the west a tributary nearly as large as itself called the Kawarau, whose discharge has been accurately gauged by Professor Park at 800,000 cubic feet per minute. This great volume of water is due to the fact that the Kawarau drains Lake Wakatipu, which serves as a vast reservoir for the drainage of a considerable area of mountain country, including snow-clad peaks at the head of the lake. The united streams continue in a south-easterly direction, and their volume is substantially increased by the Manuherikia on the east bank as well as by the Pomahaka on the west. The course of the Clutha lies through the somewhat arid schist region of Central Otago, gorge alternating with open valley and river-flats; but some ten miles or so before it reaches the sea it divides, only to reunite lower down and thus include the island known as Inch-Clutha. It almost immediately afterwards enters the sea, but its outlet is of little use as a harbour owing to a shifting and dangerous bar. Portions of its course are navigable to a very limited extent, but it is more important commercially, since it has yielded by means of dredging operations great quantities of gold; in fact, it may be regarded as a huge natural sluice-box, in which the gold disseminated through the schists of Central Otago has been concentrated through geological ages into highly payable alluvial leads.

The following large rivers belong to the Southland and Otago District, but do not reach back to the main divide—the Jacobs, Oreti, Mataura, and Taieri; and forming the northern boundary of the Otago Provincial District is the Waitaki, which drains a great area of alpine country, and includes in its basin Lakes Tekapo, Pukaki, and Ohau. Its main affluents are the Tasman and the Godley, rising in glaciers of the same names near the axis of the range where it is at its highest. As the river approaches the sea it crosses shingle-plains, through which it has cut a deep channel flanked by terraces, which rise bench-like for some hundreds of feet above the present level of the river. Its general features are similar to those of the rivers of Canterbury farther north, except that a larger proportion of the course of the latter lies across the plains and uninterfered with in any way by the underlying harder and more consolidated rocks. The four principal rivers which rise in glaciers are the Rangitata, Ashburton, Rakaia, and Waimakariri; while farther north are the Hurunui and Waiau, snow- and rain-fed rivers rising in the main range beyond the northerly limit of glaciers; and there are other streams—such as the Waihao, Pareora, Opihi, Selwyn, Ashley, and Waipara—which do not reach beyond the outer flanking ranges, and are almost entirely rain-supplied.

According to recent investigations the low-water discharge of the Waimakariri is approximately 80,000 cubic feet per minute, but it frequently rises in normal flood to 500,000 cubic feet per minute.

The rivers flowing to the East all carry down enormous quantities of shingle, but in former times they carried down even more, and built up the wide expanse of the Canterbury Plains by the coalescing and overlapping of their fans of detritus, the depth of shingle certainly exceeding 1,000 ft. Subsequently, when conditions, climatic or otherwise, slightly altered, they cut down deep through this incoherent mass of material, forming high and continuous terraces. Nowhere is the terrace system more completely developed than at the point where the rivers enter on the plains, for there the solid rock that underlies the gravels is exposed, and by the protection that it affords to the bases of old river flood-plains or former terraces it contributes materially to their preservation in a comparatively uninjured condition. The valleys of all these rivers are now almost treeless except in their higher parts, but there the mixed bush of Westland is replaced by the sombre beech forest; it is only in exceptional cases that the totara, which forms an important element of the bush on the hills to the west, crosses the range and covers portions of the sides of the valleys on the east.

Both the Hurunui and the Waiau have cut down gorges through semidetached mountain masses of older Mesozoic rock, a result probably accelerated by the movements of the earth's crust; and farther north, in Marlborough, the Clarence, Awatere, and Wairau have their directions almost entirely determined by a system of huge parallel earth-fractures, running north-east and south-west, and the rivers are walled in on either side by steep mountains for the greater part of their length. The Clarence Valley is the most gorge-like, since it lies between the great ridges known as the Seaward and Inland Kaikouras, which reach a height of about 9,000 ft. The last river of the three, the Wairau, flows for a considerable distance through a rich alluvial plain, and enters Cloudy Bay by an estuary which is practicable for small steamers as far as the Town of Blenheim. The most important of the streams on the southern shores of Cook Strait are the Pelorus, Motueka, Takaka, and Aorere, great structural faults being chiefly responsible for the position and characteristic features of the valleys of the last two.

An important commercial aspect of our rivers is their use not only as drainage channels, but as a source of water for pastoral purposes. Hardly any area is without water for stock or with a subsoil wanting in moisture necessary for successful cultivation. Only in Central Otago and on the Canterbury Plains were there formerly wide stretches of arid country, but the deficiency in the water-supply has been remedied by well-engineered systems of races, tapping unfailing streams at higher levels, and distributing a portion of their contents far and wide, so that the districts mentioned are rendered highly productive and absolutely protected from the serious effects of drought. It is, however, the rich alluvial flats and well-drained terrace lands bordering on the rivers that contribute specially to the high average yield per acre year after year for which this country has such a world-wide reputation.

From the brief summary given above it will be evident also that in her rivers the country possesses enormous stores of energy awaiting exploitation. A beginning has been made in some places, such as at Waipori in Otago, at Lake Coleridge in Canterbury, at the Horohoro Falls and at Arapuni on the Waikato River in Auckland, at Mangahae in Wellington, and at a few other places where there are minor installations. These owe their development to their comparative nearness to centres of industry; but they represent an infinitesimal portion of the energy available, and the value of our vast store will be more truly appreciated when our somewhat limited reserves of coal show signs of failure or become difficult to work—unless, indeed, some new form of power is disclosed by the researches of science in the near future.

A list of the more important rivers of New Zealand is given, with their approximate lengths, the latter being supplied by the Department of Lands and Survey.

| Flowing into the Pacific Ocean— | Miles. |

| Piako | 60 |

| Waihou (or Thames) | 90 |

| Rangitaiki | 95 |

| Whakatane | 60 |

| Waiapu | 55 |

| Waipaoa | 50 |

| Wairoa | 50 |

| Mohaka | 80 |

| Ngaururoro | 85 |

| Tukituki | 65 |

| Flowing into Cook Strait— | |

| Ruamahanga | 70 |

| Hutt | 35 |

| Otaki | 30 |

| Manawatu (tributaries: Tiraumea and Pohangina) | 100 |

| Rangitikei | 115 |

| Turakina | 65 |

| Wangaehu | 85 |

| Wanganui (tributaries: Ohura, Tangarakau, and Maunganuite-ao) | 140 |

| Waitotara | 50 |

| Patea | 65 |

| Flowing into the Tasman Sea— | |

| Waitara (tributary: Maunganui) | 65 |

| Mokau | 75 |

| Waikato (tributary: Waipa) | 220 |

| Wairoa | 95 |

| Hokianga | 40 |

| Flowing into Cook Strait— | Miles. |

| Aorere | 45 |

| Takaka | 45 |

| Motueka | 75 |

| Wai-iti | 30 |

| Pelorus | 40 |

| Wairau (tributary: Waihopai) | 105 |

| Awatere | 70 |

| Flowing into the Pacific Ocean— | |

| Clarence (tributary: Acheron) | 125 |

| Conway | 30 |

| Waiau (tributary: Hope) | 110 |

| Hurunui | 90 |

| Waipara | 40 |

| Ashley | 55 |

| Waimakariri (tributaries: Bealey, Poulter, Esk, and Broken River) | 93 |

| Selwyn | 55 |

| Rakaia (tributaries: Mathias, Wilberforce, Acheron, and Cameron) | 95 |

| Ashburton | 67 |

| Rangitata | 75 |

| Opihi | 50 |

| Pareora | 35 |

| Waihao | 45 |

| Waitaki (tributaries: Tasman, Tekapo, Ohau, Ahuriri, and Hakataramea) | 135 |

| Kakanui | 40 |

| Shag | 45 |

| Taieri | 125 |

| Clutha (tributaries: Kawarau, Makarora, Hunter, Manuherikia, and Pomahaka) | 210 |

| Flowing into Foveaux Strait— | |

| Mataura | 120 |

| Oreti | 105 |

| Aparima | 65 |

| Waiau (tributaries: Mararoa, Clinton, and Monowai) | 115 |

| Flowing into the Tasman Sea— | |

| Cleddau and Arthur | 20 |

| Hollyford | 50 |

| Cascade | 40 |

| Arawata | 45 |

| Haast (tributary: Landsborough) | 60 |

| Karangarua | 30 |

| Fox | 25 |

| Waiho | 20 |

| Wataroa | 35 |

| Wanganui | 35 |

| Waitaha | 25 |

| Hokitika (tributary: Kokatahi) | 40 |

| Arahura | 35 |

| Taramakau (tributaries: Otira and Taipo) | 45 |

| Grey (tributaries: Ahaura, Arnold, and Mawhera-iti) | 75 |

| Buller (tributaries: Matakitaki, Maruia, and Inangahua) | 105 |

| Mokihinui | 30 |

| Karaniea | 45 |

| Heaphy | 25 |

The following article on the lakes of New Zealand is also by Professor R. Speight:—

Lakes are features of the landscape which are usually attributable to the filling-up of hollows formed by faulting or warping, or by volcanic explosions, or by the irregular accumulation of material round volcanic vents, or to the interference with river-valleys by glaciers. Seeing that all these agencies have operated on an extensive scale in New Zealand in comparatively recent geological times, it is not surprising that its lake systems are well developed. The remarkable group of lakes lying in the middle of the North Island, as well as isolated enclosed sheets of water in other parts of the Auckland Provincial District, are due to volcanic action in its various forms, while those in the South Island are to be credited to the operations of glaciers. We have therefore two distinct types of lake scenery, one for each Island. The relief of the land near the volcanic lakes is not by any means marked, and they therefore rarely have bold and precipitous shores, and their scenic interest depends partly on the patches of subtropical bush which grows luxuriantly in places on the weathered igneous material, and partly on their desolate and forbidding surroundings, everywhere reminiscent of volcanic action, where the softening hand of time has not reduced the outpourings of the eruptive centres to a condition favourable for the establishment of vegetation. The thermal activity which is manifested in numerous places on their shores adds to their interest. In the South Island the lakes lie in the midst of splendid mountain scenery, with amphitheatres of noble peaks at their heads, crowned with perpetual snow, and clad at lower levels with dark primeval beech forest, which affords an appropriate setting for the waters at their base, rendered milky-white at times with the finest of sediment worn from solid rocks by powerful glaciers, and swept down to the quiet waters of the lake by turbulent glacial torrents.

The largest sheet of fresh water in New Zealand is Lake Taupo, which is situated in the very heart of the North Island, at an elevation of 1,211 ft. above the sea. Its greatest length in a S.W.-N.E. direction is twenty-five miles, and its greatest breadth is about seventeen miles, but its shape is somewhat irregular owing to a large indentation on its western side. Its area is 238 square miles, its greatest depth is 534 ft., and it has a catchment area of about 1,250 square miles. About 60 per cent, of its water-supply comes from the Upper Waikato River, which drains the northern and eastern flanks of the central volcanoes as well as the western slopes of the Kaimanawa Range and its northern extensions. The lake discharges at its northeastern corner and forms the main Waikato River, which falls within a short distance over the Huka Falls, where the volume of water which passes over is estimated to reach an average of 5,000 cubic feet per second. The surroundings of the lake are picturesque, on the western side especially. Here it is bounded by cliffs of volcanic rock, generally between 100 ft. and 800 ft. in height, but at the Karangahape Bluffs they rise to over 1,000 ft. sheer. The northern shore is bold with promontories terminated with bluffs and intervening bays with gentler slope. The south side is generally fringed with alluvial flats, while the cast is bordered in places with pumice cliffs, and is somewhat uninteresting, but relieved from absolute monotony by the graceful extinct cone of Tauhara. About twenty miles to the south rise the great volcanic peaks of Tongariro, Ngauruhoe, and Ruapehu, with their bush-clad foothills, forming a splendid panorama when seen from the northern shore of the lake.

To the south-east of the middle of the lake lies the Island of Motutaiko, in all probability the summit of a volcanic cone on the line of igneous activity which stretches north-east from the central volcanoes towards Tarawera, White Island, Tonga, and Samoa. The formation of the lake itself is attributable either to a great subsidence after volcanic activity waned, or to a great explosion which tore a vast cavity in the earth's crust and scattered the fragments far and wide over the middle of the Island; and evidence of declining igneous action is furnished by hot springs in the lake itself and near its shore, especially at the north-east corner near Wairakei and on the southern shore near Tokaanu. Earth-movements have in all probability continued down to recent times, for an old shore platform or wave-cut terrace surrounds the lake, indicating that its waters were formerly at a higher level, and changes in level of the ground on the northern shore of the lake, attended by local earthquakes, occurred during the year 1922.

The lake forms an enormous reservoir of power conveniently placed for exploitation; it is estimated that the Huka Falls would develop up to 38,000 horse-power, and its central position renders it peculiarly suitable for supplying a wide district. Although the immediate vicinity does not hold out much hope for its utilization, the rich agricultural districts which lie at some distance will no doubt rely on it in the near future as a convenient source of mechanical energy.

To the south of Taupo, nestling in the hills between the great lake and the northern slopes of Tongariro, lies Roto-Aira, a beautiful sheet of water, three miles in length and with an area of five square miles. It discharges by the Poutu River into the Upper Waikato. The other lakes of this region are small in size and usually occupy small explosion craters on the line of igneous activity mentioned above.

A most interesting group of lakes lies in the midst of the thermal region to the north-east of Taupo. These comprise the following: Rotorua, Roto-iti, Roto-ehu, and Rotoma, which belong to a system lying to the north-west of the area, and Tarawera, Rotokakahi, Tikitapu, Okareka, Rotomahana, Okataina, Rotomakariri, and Herewhakaitu, which lie to the south-cast. The former group is connected either directly or indirectly with the Kaituna River basin, and the latter with the Tarawera River basin, both of which discharge their waters into the Bay of Plenty. All these lakes occupy either explosion craters or depressions due to subsidences of the crust or hollows formed by irregular volcanic accumulations. They lie at an elevation of about 1,000 ft. above the sea. The largest is Rotorua, which is nearly circular in shape, except for a marked indentation on the southern shore. It is 32 square miles in area, and 84 ft. deep, with flat shores; but in the middle, rather towards the eastern side, the picturesque and historical Island of Mokoia rises to a height of 400 ft. The lake discharges at its north-eastern corner by the Ohau Creek into Lake Roto-iti, a shallow and irregular depression, which runs in turn into the Okere River. To the north-east lies the small lake of Roto-ehu, separated from it by low ground, and farther on lies the picturesque Rotoma, of still smaller size.

The largest lake of the south-eastern group is Tarawera, lying to the north and west of the mountain of the same name; discharging directly into it are Rotokakahi, Okareka, and Okataina, the last two by subterranean channels, while Tikitapu and Rotomahana are separated from it by comparatively narrow ridges.

All these lakes owe their interest to the thermal manifestations which occur in their vicinity, and to the remnants of beautiful bush which have survived the eruption of Tarawera in 1886. They are also noted for their fishing, being well stocked with trout. Their water is available for power purposes to a limited extent, and a small installation is placed near the low fall where the Okere River discharges from Lake Roto-iti.

Two small lakes of volcanic origin are situated on the peninsula north of Auckland: these are Takapuna and Omapere. The former lies close to the City of Auckland, and occupies a small explosion crater near the sea; while Omapere is between the Bay of Islands and Hokianga, in a shallow depression, which owes its origin to the obstruction of the Waitangi River by a lava-flow. It is three miles long by two wide, and is placed at a height of 790 ft. above the sea.

About forty miles from the east coast, in the Hawke's Bay District, lies the most important lake of Waikaremoana, twelve miles in length by about six miles and a quarter in breadth at its widest part, but with an extremely irregular outline; it has an area of twenty-one square miles. Its surface is 2,015 ft. above the sea, and it has a maximum depth of 846 ft. It discharges by the Wairoa River to the northern shore of Hawke Bay. This lake is most favourably situated for the development of water-power, and it is estimated that it would generate, owing to its admirable position, as much as 136,000 horse-power. A few miles to the northeast lies the small lake called Waikare-iti, which discharges into the large lake.

The only other inland lakes of any importance in this Island are those situated in the lower course of the Waikato River, the most noteworthy being Waikare and Whangape. The former has an area of nearly eleven square miles and has a depth of 12 ft.; the latter is smaller, with an area of only four square miles and a depth of 9 ft. These owe their origin to flooding of low-lying land alongside the river—in all probability attributable to a slight lowering of the land in this part of the country, with the consequent inability of the river to discharge its surplus water without a proper channel being maintained.

Along the coast-line, especially behind the fringe of dunes, numerous small lakes are found, such as Rotokawa, near Kaipara, and Horowhenua, near Levin; and a large sheet of water occurs near the mouth of the Wairarapa Valley, called Lake Wairarapa. The lake is very shallow, and is liable to remarkable variations in size owing to heavy floods from the neighbouring ranges. Between it and the sea is a considerable area of swampy ground in which are several small lakes, the largest of which, Lake Onoke, is separated from Palliser Bay by a narrow shingle-spit.

By far the great majority of the lakes of the South Island are dependent for their formation either directly or indirectly on the action of glaciers. They may be small tarns high on the mountains, large lakes occupying considerable lengths of old stream-valleys which have been overdeepened by the excavating power of ice during the Pleistocene glaciation, or lakes formed by the filling of hollows in the irregular heaps of debris laid down on a plain at the base of the mountains or in a wide open valley. Accumulations of debris may also assist the first two causes in the formation of lakes, and some may owe the initial formation of their basins to tectonic causes, but these have been modified profoundly by other influences.

Included in the first class are numerous sheets of water from the size of small ponds upwards, found in all parts of the mountain region, but especially in the high plateau regions of western Otago, and to a limited extent in north-west Nelson. To the second group belong the large lakes of the eastern watershed of the Alps and a small number which drain west, such as Rotoroa and Rotoiti in the Buller Basin, while to the last must be assigned the majority of the lakes of Westland; but Brunner and Kanieri should perhaps be assigned to the second class.

Seeing that glaciation was not so intense in the northern portion of the Island, it is not surprising that the lakes of that region are small and few in number. Attention has, however, been drawn to Boulder Lake, in the valley of the Aorere River, since it might be used for power purposes in connection with the great deposit of iron-ore at Parapara. It is only 151 acres in extent, but it lies at an elevation of 3,224 ft., and is conveniently placed for the establishment of an electric-power plant. Farther south, near the head of the Buller, are two larger lakes— Rotoroa and Rotoiti—occupying ice-eroded valleys dammed at their lower ends by moraine. The former has an area of eight square miles, and the latter two and three-quarter square miles; their heights above the sea being respectively 1,470 ft. and 1,997 ft., and Rotoiti being 228 ft. deep.

In the valley of the Grey River are two lakes of considerable size—viz., Brunner and Poerua. These are shrunken and separated parts of a former extensive sheet of water which was ponded back behind a great glacier moraine. Lake Brunner is five miles long by four broad, has an area of 15.9 square miles, is 280 ft. above sea-level, and 357 ft. deep. It is surrounded on two sides by high wooded granite peaks, and on the other two by low ground. It discharges by the Arnold River to the Grey, but a very slight change of level would turn it into the Taramakau.

Lake Kanieri, which lies in the basin of the Hokitika River at the base of Mount Tuhua, is a beautiful sheet of water. It is five miles long by one and three-quarters wide, has an area of eight square miles, is 422 ft. above sea-level, and 646 ft. deep. It owes its origin partly to the hollow formed behind an immense morainic dam, and partly to the erosive action of the valley glacier. Farther south on the coastal plain of Westland are numerous small and picturesque lakes, wooded to the water's edge, lying behind heaps of glacial debris or in ice-eroded basins. The most notable of these are Ianthe and Mapourika, both of small size, the former with an area of only two square miles, at a height of 80 ft. above sea-level, and with a depth of 105 ft., and the latter remarkable for the fine panorama of mountain scenery, with Mount Cook in the background, which can be obtained from the shore of the lake. Along this strip of coast-line there are numerous lagoon-like expanses of water, cut off from the sea by areas of dune or of moraine, the chief of which is Mahinapua, which lies close to the Town of Hokitika. This is but 6 ft. above tide water, and has an area of one and a half square miles. The creek discharging from it is noted for the perfect reflections to be seen in the dark, peat-stained water.

On the eastern side of the main divide lie the great valley lakes which belong to the following river-basins: Hurunui—Lake Sumner; Rakaia—Lakes Coleridge and Heron; Waitaki—Lakes Tekapo, Pukaki, and Ohau; Clutha—Lakes Wanaka, Hawea, and Wakatipu; Waiau—Lakes Te Anau, Manapouri, and Monowai; Wairaurahiri—Lake Hauroko; Waitutu-Lake Poteriteri. These are all formed on the same plan; great glaciers have excavated the floor of a river-valley and have piled the debris across its lower portion, leaving a great hollow which was filled with water when the ice retreated. Even in those river-basins where no lakes now exist the traces of their former presence are evident; especially is this the case with the Waimakariri, Rakaia, and Rangitata Valleys. Besides these large lakes each valley has its quota of small ones, usually hidden away among the piles of moraine or ponded back behind shingle-fans. Among these small lakes should be noted the following: Tennyson, in the valley of the Clarence; Taylor, Sheppard, Katrine, and Mason, in the Hurunui; Pearson, Grassmere, and Letitia, in the valley of the Waimakariri; Evelyn, Selfe, Catherine, Ida, and Lyndon, in that of the Rakaia; Clearwater (or Tripp), Howard, and Acland, in the Ashburton; Alexandrina, in the Waitaki; Lochnagar, Hayes, and Moke, in the Clutha. In the valley of the Waiau there are numerous lakes of small size hidden away in bush-clad valleys, the chief of which is Mayora, which discharges into the main Waiau by way of its large tributary, the Mararoa. On the west coast of this region are also many insignificant lakes as far as size is concerned, such as Lake Ada, a well-known beauty-spot on the Milford Sound track, while farther north McKerrow, a lake of larger size, discharges into Martin's Bay.

The only other lakes in this Island that are worthy of mention are Waihola, Forsyth, and Ellesmere. The first mentioned occupies the lower portion of the Taieri Plain, and drains to the sea by a deep winding gorge cut through a ridge of rock-covered hills, the gorge being tidal for the greater part of its length. Lakes Forsyth and Ellesmere lie on the coast immediately south of Banks Peninsula, both ponded back behind a great shingle-spit formed by the drift of material brought down by the rivers and carried north under the influence of a strong shore current. Both are very shallow and liable at times to be invaded by the sea. Ellesmere is sixteen miles long by about ten broad, and Forsyth is about six miles long by one in breadth.

Among all these lakes three stand pre-eminent for their scenic interest—Wakatipu, Te Anau, and Manapouri. The first-named is walled in on both sides by steep mountains which rise at the head of the lake to over 8,000 ft. in the Humboldt Range, and to over 9,000 ft. in Mount Earnslaw. Te Anau has an uninteresting eastern shore, but its western shore is broken into three great arms, whose impressive scenery is strongly reminiscent of that of Milford Sound and George Sound; while Manapouri, with its many bush-clad islets and its indented shore-line with innumerable sheltered coves and pebbly beaches, belongs to the same type as Dusky Sound, the most beautiful of all in the fiord region.

The lakes of Canterbury lie in a treeless area and owe their scenic interest principally to the background of snowy peaks, while Wanaka and Hawea are intermediate in character between them and the more southern lakes of Otago.

The following is a summary of the statistics of the chief lakes of New Zealand:—

| Lake. | Length, in Miles. | Greatest Breadth, in Miles. | Area, in Square Miles. | Drainage Area, in Square Miles. | Approximate Volume of Discharge, in Cubic Feet per Second. | Height above Sea-level, in Feet. | Greatest Depth, in Feet. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Island. | |||||||

| Taupo | 25 | 17 | 238 | 1,250 | 5,000 | 1,211 | 534 |

| Rotorua | 7 1/2 | 6 | 32 | 158 | 420 | 915 | 84 |

| Rotoiti | 10 3/4 | 2 1/4 | 14 | 26 | 500 | 913 | 230 |

| Tarawera | 6 1/2 | 6 1/2 | 15 | 75 | 1,032 | 285 | |

| Waikaremoana | 12 | 6 1/4 | 21 | 128 | 772 | 2,015 | 846 |

| Waikarapa | 10 | 4 | 27 | 1,250 | 64 | ||

| South Island. | |||||||

| Rotoiti | 5 | 2 | 2 3/4 | 86 | 1,997 | 228 | |

| Rotoroa | 7 | 2 1/2 | 8 | 146 | 1,470 | ||

| Brunner | 5 | 4 | 16 | 145 | 280 | 357 | |

| Kanieri | 5 | 1 3/4 | 8 | 11 | 422 | 646 | |

| Coleridge | 11 | 3 | 18 | 70 | 1,667 | 680 | |

| Tekapo | 12 | 4 | 32 | 580 | 5,000 | 2,323 | 620 |

| Pukaki | 10 | 5 | 31 | 515 | 6,000 | 1,588 | |

| Ohau | 10 | 3 | 23 | 424 | 5,000 | 1,720 | |

| Hawea | 20 | 5 | 48 | 518 | 5,700 | 1,062 | |

| Wanaka | 30 | 4 | 75 | 960 | 922 | ||

| Wakatipu | 52 | 3 | 112 | 1,162 | 13,000 | 1,016 | 1,242 |

| Te Anau | 33 | 6 | 132 | 1,320 | 12,660 | 694 | 906 |

| Manapouri | 12 | 6 | 56 | 416 | 596 | 1,458 | |

| Monowai | 12 | 1 | 12 | 51 | 700 | 600 | |

| Hauroko | 20 | 3 | 25 | 195 | 1,800 | 611 | |

| Poteriteri | 17 | 2 | 17 | 162 | 96 | ||

| Waihola | 4 1/2 | 1 1/8 | 3 1/3 | 2,200 | (Tidal) | 52 | |

| Ellesmere | 16 | 10 | 107 1/2 | 745 | (Tidal) | 45 |

A reference to the section of this book dealing with water-power will give an idea of the enormous amount of energy awaiting development in the lakes of the South Island. The only one yet utilized to any great extent for hydro-electric purposes is Coleridge, in Canterbury. Some use is also being made of Monowai, in Southland, and Waikaremoana, in the North Island. The latter will be developed to a much greater extent in the near future, and will form one of three great schemes for supplying the hydro-electric requirements of the whole of the North Island.

The following article on the geology of New Zealand was prepared by the late Mr. P. G. Morgan, M.A., F.G.S. (Director), and other members of the Geological Survey:—

The geological history of New Zealand is long and complicated, and is as yet by no means clearly deciphered. Since the beginning of the Palæozoic era that portion of the earth's crust where New Zealand is shown on the map has many times been elevated and depressed. Sometimes the land and the neighbouring ocean-floor as a whole have risen or fallen; at other times movement has been more or less local. Thus from age to age the land has greatly varied in outline, and whilst in one period it becomes a continent, in another it nearly or quite disappears beneath the ocean. The actual surface has been almost equally variable, for the mountain-chains of early periods have been planed down by denudation, and new mountains have risen to take their places. In short, the story of the land has been one of incessant, though as a rule slow-moving, change, and if the student would rightly interpret that story he must ever bear in mind that New Zealand in the past has never been quite or even nearly the same as we see it now. With the scanty materials at hand he must endeavour to reconstruct the land as it existed during past ages. A rich field for original research is open to the New Zealand geologist. Little has yet been accomplished in comparison with what remains to be done. There are many absorbing problems—some of great economic importance, some of world-wide interest—awaiting solution by the patient scientific worker.

Professor James Park writes: “Though so isolated, New Zealand contains within its narrow borders representatives of most of the Palæozoic, Mesozoic, and Cainozoic formations. Moreover, its structure is that usually associated with areas of continental dimensions; and for that reason it is often spoken of as an island of the continental type. It is a miniature continent; and the occurrence in its framework of thinogenic [shore or shallow-water] rocks, ranging from the earliest geological epochs to the present day, is undeniable evidence that it stands on a subcrustal foundation of great stability.” (N.Z. Geological Survey Bulletin No. 23, p. 24, 1921.)

The oldest rocks in New Zealand appear to be those of western Otago, where over a large area is exposed a complex of gneisses and schists, intruded by granite and other igneous rocks. The gneisses in the main are altered granites and diorites, but some of the schists, at any rate, are of sedimentary origin. A pre-Cambrian age was assigned to these rocks by Professor F. W. Hutton, but Professor James Park considers them to be probably of Cambrian age, and includes them in his Dusky Sound Series, the lower part of the Manapouri System.

Perhaps next in age to the western Otago gneisses and schists are the mica, chlorite, and quartz schists of Central Otago. In the absence of fossils, however, the age of these rocks is uncertain. Professor Hutton regarded them as pre-Cambrian, Professor Park assigns a Cambrian age, whilst Dr. P. Marshall considers them to be little, if at all, older than the Triassic. Recent field-work by the Geological Survey, however, strongly suggests that an unconformity separates the Triassic rocks of the Nugget Point district from the greywackes of the Balclutha district, which overlie the Otago schists. In December, 1924, fossils of Permian (if not older) age were discovered near Clinton in greywacke and associated rocks. The horizon of these fossils is far above the schists, and therefore a pre-Permian age for the schists is undeniable. Some schistose rocks in north, central, and western Nelson may be as old as, or even older than, the Otago mica-schists The gneisses and schists on the western side of the Southern Alps may for the present be classed with the Nelson schists.

The oldest known fossiliferous rocks in New Zealand are the Ordovician argillites (“slates”), greywackes, and quartzites occurring near Collingwood (Nelson), in the Mount Arthur district, and near Preservation Inlet in south-west Otago. Ordovician rocks probably have a considerable development in other parts of Nelson and in Westland, but no recognizable fossils have been found in those areas.

Rocks containing Silurian fossils occur in the Mount Arthur, Baton River, and Reefton districts, Nelson. They are principally altered limestone, calcareous shale or argillite, sandstone, and quartzite.

Considerable areas have been assigned to the Devonian period by Mr. Alexander McKay, but owing to the non-discovery of recognizable fossils definite proof of age is wanting. For a similar reason the age of most of the rocks placed in the Carboniferous period (“Maitai Series”) by McKay is uncertain. At Reefton the supposed Carboniferous rocks, which here contain many auriferous quartz-veins, are almost certainly of Ordovician age. In the typical locality near Nelson the fossils found in the Maitai rocks, according to Dr. C. T. Trechmann, indicate a Permo-Carboniferous age.

So far Permian rocks have not been satisfactorily identified in New Zealand, but, as previously stated, fossiliferous strata of this age, or slightly older, have been found near Clinton, Otago. The Maitai rocks near Nelson ought probably to be classified as Permian rather than as Permo-Carboniferous. Park considers his Aorangi Series to be of Permian age.

During some of the Palæozoic periods it is conjectured that New Zealand formed part of or was the foreland of a large land-mass that extended far to the west. This land-mass possibly persisted to late Palæozoic times, and may have been the now dismembered and all-but-lost continent known to geologists as Gondwanaland.

Since Hochstetter's visit (1859), Triassic and Jurassic rocks have been known to exist in New Zealand but the fossils were not extensively and accurately identified until the last decade, when Newell Arber and Trechmann published their valuable papers.

Newell Arber (1917) described an Upper Triassic flora from Mount Potts and Clent Hills (North Canterbury), and Hokonui Hills (Southland); Jurassic floras from North Canterbury and Southland; and a Lower Cretaceous flora from the neighbourhood of Oruarangi Point, south of Waikato South Head. Trechmann (1918 and 1923) examining marine molluses and brachiopods from several localities, found that they ranged in age from Upper Triassic to Upper Jurassic, and correlated the different beds with European stages. The most fossiliferous localities are Hokonui Hills (Southland), near Nugget Point (Otago), Wairoa Valley (Nelson), Mokau watershed, Kawhia Harbour, and Waikato South Head, the three last-mentioned on or near the west coast of Auckland.

A broad belt of largely unfossiliferous but probable Trias-Jura rocks extends through western Canterbury and Marlborough, and is continued as a somewhat narrower belt on the north side of Cook Strait from Wellington to northern Hawke's Bay. Rocks of much the same appearance occur in the Lower Waikato Valley, in the Coromandel Peninsula, and in North Auckland. Some of these rocks may be of pre-Mesozoic age, but fossils to settle the point have not yet been found.