Table of Contents

SINCE the First Part of the Year-book was printed the following changes have taken place:—

FOREIGN CONSULS (See p. 23).

French Vice-consulship at Wellington abolished. Viscount Alexandre Louis Ferdinand de Jouffroy D'Abbans appointed to act as French Consul at Wellington.

EXTRA AIDE-DE-CAMP (See p. 26).

Captain R. W. P. Clarke-Campbell-Preston appointed, vice Captain Stewart, resigned.

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL (See p. 28).

Honourable Robert Hart, since deceased.

BISHOPS (See p. 31).

For the Bishopric of Waiapu, the Venerable Archdeacon William Leonard Williams, B.A., has been elected by the Diocesan Synod.

For the Bishopric of Wellington, the Reverend Frederick Wallis, M.A., has been nominated. Consecration fixed for 25th January, 1895.

LATESTESTIMATESOF POPULATION.

The Colony: June, 1894 (excluding Maoris)—678,586 persons. Capital City, Wellington, January, 1894—35,013 persons, or, including suburbs, 38,298.

LANDFOR SETTLEMENTS ACT, 1894.

The passing of this Act alters that of 1892 by empowering the Government to take land compulsorily, where it is necessary, for small holdings, and where no agreement can be come to with the owners. It also allows of the exchange of high pastoral country belonging to the Crown for agricultural land suitable for small holdings. The sum which may be expended annually in acquisition of lands has been increased to £250,000.

ERRATUM.

On p. 39.—Native Land Court Judges: Add “H. W. Brabant.” Recorders Delete the same name.

Two important financial Acts, the New Zealand Consols Act and the Government Advances to Settlers Act, have also been passed.

“THE NEW ZEALAND CONSOLS ACT, 1894.”

The purpose of this Act is, by providing an inscription of New Zealand Consols, to give further facilities for the safe investment of savings. Practically, it establishes another branch of the Government Savings-Bank, with extended power of investment. Under section 3 the Colonial Treasurer is authorised to receive by way of deposits from persons in the colony sums of money up to £500,000, but the amount deposited in any one year must not be more than £250,000. The currency of such deposits is not to exceed forty years; the rate of interest shall not be above 4 per cent. per annum, and will probably be fixed at 31/2 per cent.

In case an inscriber desires to make use of his deposit, or any portion of it, to the extent of £5, or a multiple of £5, he can obtain a Consols certificate, which is payable to bearer and is transferable by delivery. This certificate entitles the holder to receive interest half-yearly at the same rate as the original inscription. and also to payment of the principal sum on the due date.

The Act also provides for the deposit of moneys by minors, which, it is felt, will be very acceptable to parents in encouraging habits of thrift in their children.

Post-office Money-order Offices throughout the colony will be made use of to receive applications for inscription, and also for payment of the half-yearly interest on the amounts deposited.

“THE GOVERNMENT ADVANCES TO SETTLERS ACT, 1894.”

This Act enables the Government to assist settlers by advancing money to them on mortgage at a reasonable rate of interest. The term of the mortgage will be for thirty-six years and a half. The loan will be repayable by half-yearly instalments of £3 for every £100 advanced, including 5 per cent. per annum for interest and 1 per cent. per annum for redemption of the principal sum.

Such advances can be made on rural lands only, up to three-fifths of the value of the property, and the maximum amount of a loan to any one borrower is fixed at £2,500, and the minimum at £25.

The Government have power to raise a sum not exceeding three millions, of which only one and a half millions shall be raised in each year for two years; and the power to raise the three millions shall absolutely cease at the end of two years from the date of the passing of the Act.

Interest on the money borrowed for the purposes of the Act is to be at the rate of 31/2 per cent. per annum, and the difference of 11/2 per cent. between this rate and the 5-per-cent. rate charged to the borrower will be used to provide an assurance fund of one-half per cent., and to defray the expenses of administering the Act.

A General Board and District Boards are to be established; also a Superintendent, who shall be Chairman of the General Board; Valuers will be appointed to assist the Boards, and fees according to scale will require to be paid by borrowers.

THE Year-book for 1894 will be found to contain the usual revised official information, and statistics in the form of a considerably enlarged report, which, with some exception, gives figures brought down to the end of the year 1893.

To do the fullest justice to the statistics of 1893 in the report, it would have been necessary to delay the publication of the Year-book until the early part of 1895, printing the work after the termination of the present session of Parliament. Some of the figures were available only at the time when, to meet the present requirement, it was necessary to begin printing, and there was not sufficient time for exhaustive analysis in respect of several heads of information. But the report is nevertheless far more complete than was the previous one, and the statistics relating to last year are published earlier than in the neighbouring colonies.

There has also been difficulty about some of the special articles, because new information was continually coming out in departmental reports during the time that the book was in the press, and fresh legislation has been in progress.

Of the special articles, seventeen are entirely new, the rest being matter which it has been found desirable to give again after revision. Most of these articles will be extensively circulated separately in pamphlets, besides forming part of this work.

Although the number of copies printed of the previous Year-book (1893) was very considerable, and far in excess of the number struck off of the original Handbook for 1892, the supply has not been found in excess of the demand; and consideration of this fact has led to the reproduction of some matter which will probably be kept for leaflets only after this year.

The assistance of the various Government Departments is gratefully acknowledged.

E. J. VON DADELSZEN.

Registrar-General's Office,

Wellington, 29th September, 1894.

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

THE Colony of New Zealand consists of three main islands, with several groups of smaller islands lying at some distance from the principal group. The main islands, known as the North, the Middle, and Stewart Islands, have a coast-line amounting to 4,330 miles in length—North Island, 2,200 miles; Middle Island, 2,000 miles; and Stewart Island, 130 miles. The other islands now included within the colony are the Chatham Islands, Auckland Islands, Campbell Islands, Antipodes Islands, Bounty Islands, and Kermadec Islands. A protectorate over the Cook Islands (Hervey Group) is exercised by the Imperial Government, the Governor of New Zealand acting as responsible adviser.

New Zealand is mountainous in many parts, but has, nevertheless, large plains in both North and Middle Islands. In the North Island, which is highly volcanic, is situated the famous Thermal-Springs District, of which a special account will be given. The Middle Island is remarkable for its lofty mountains, with their magnificent glaciers, and the deep sounds or fiords on the western coast.

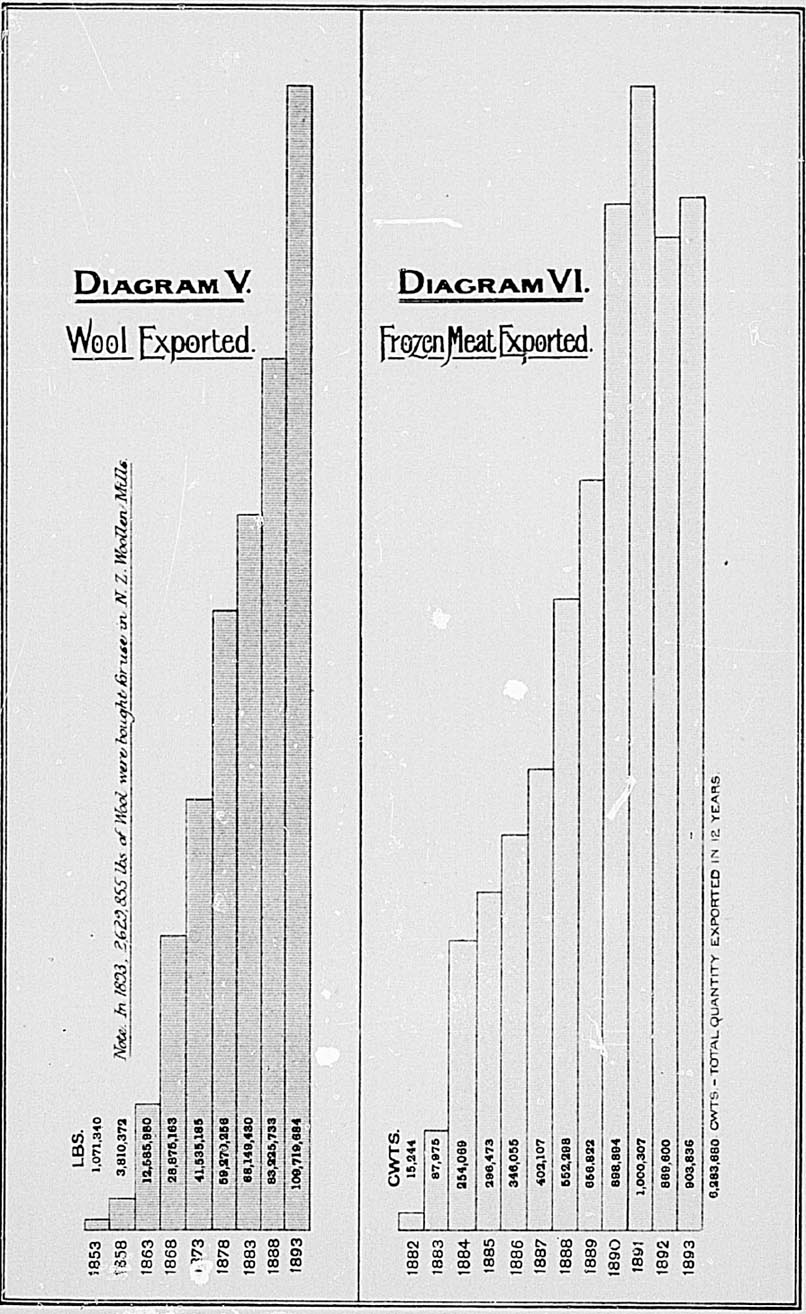

New Zealand is firstly a pastoral, and secondly an agricultural country. Sown grasses are grown almost everywhere, the extent of land laid down being upwards of eight millions of acres. The soil is admirably adapted for receiving these grasses, and, after the bush has been burnt off, is mostly sown over without previous ploughing. In the Middle Island a large area is covered with native grasses, all used for grazing purposes. The large extent of good grazing-land has made the colony a great wool- and meat-producing country; and its agricultural capabilities are, speaking generally, very considerable. The abundance of water and the quantity of valuable timber are also leading characteristics.

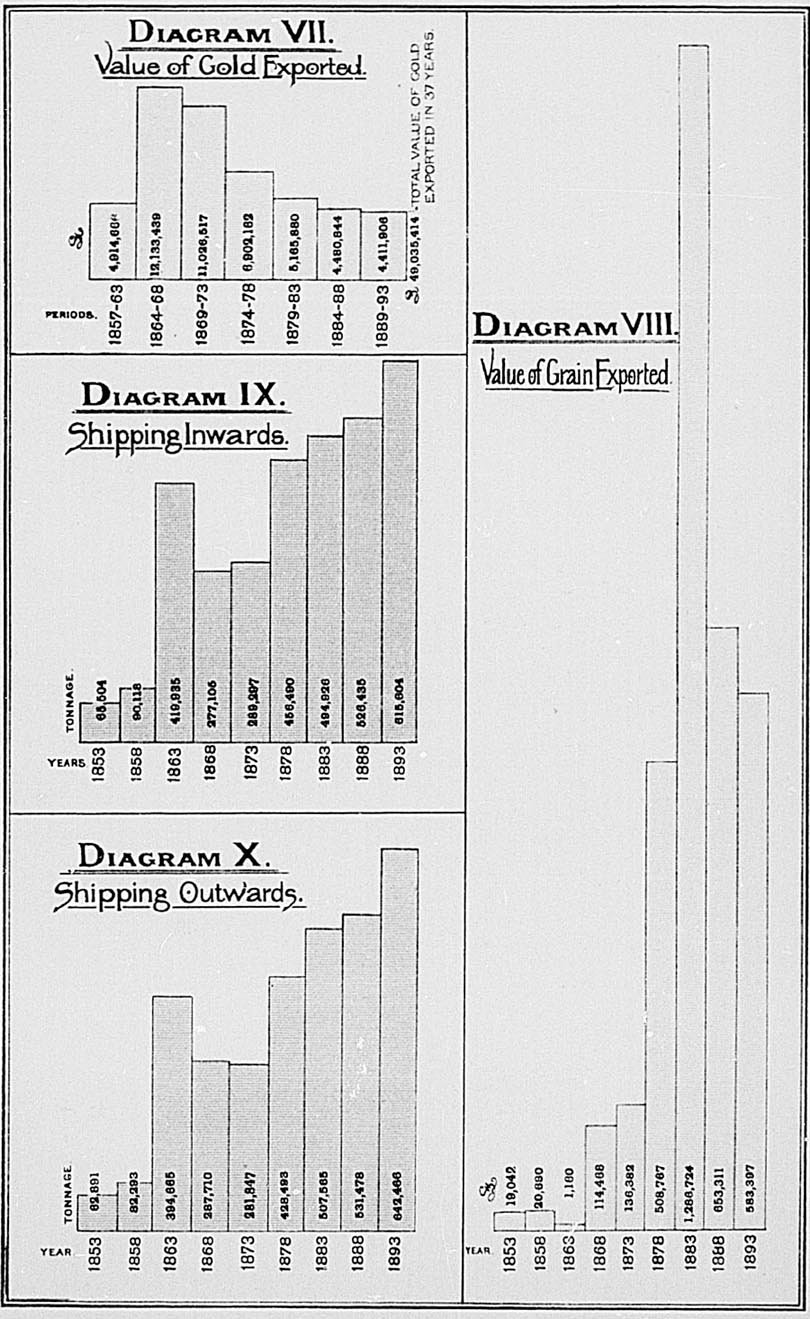

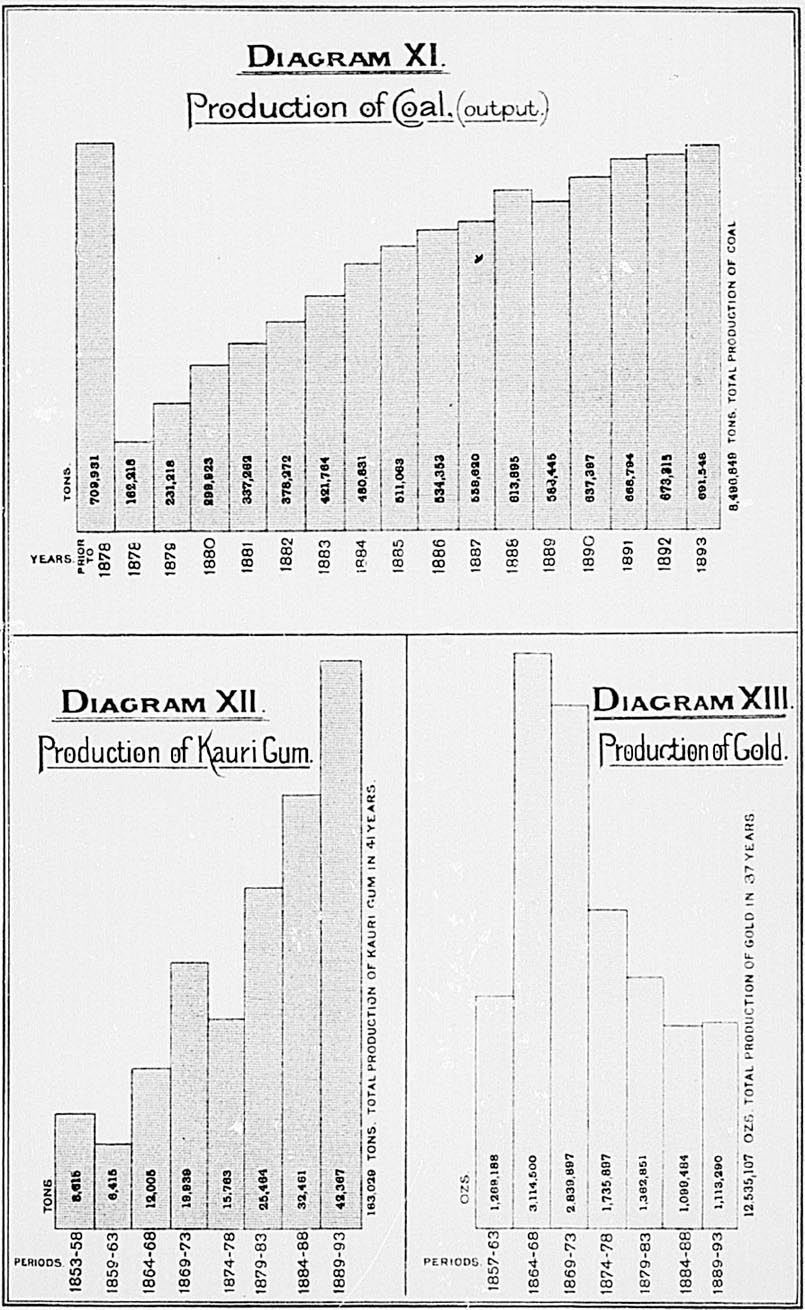

New Zealand is, besides, a mining country. Large deposits of coal are met with, chiefly on the west coast of the Middle Island. Gold, alluvial and in quartz, is found in both islands, the yield having been over forty-nine millions sterling in value to the present time. Full statistical information on this subject is given further on, compiled up to the latest dates.

The first authentic account of the discovery of New Zealand is that given by Abel Jansen Tasman, a Dutch navigator. He left Batavia on the 14th August, 1642, in the yacht “Heemskirk,” accompanied by the “Zeehaen” (or “Sea-hen”) fly-boat. After having visited Mauritius and discovered Tasmania, named by him “Van Diemen's Land,” in honour of Anthony van Diemen, the Governor of the Dutch possessions in the East Indies, he steered eastward, and on the 13th December of the same year sighted the west coast of the Middle Island of New Zealand, described by him as “a high mountainous country, which is at present marked in the charts as New Zealand.”

Tasman, under the belief that the land he saw belonged to a great polar continent, and was part of the country discovered some years before by Schouten and Le Maire, to which the name of Staaten Land had been given, gave the same name of Staaten Land to New Zealand; but within about three months after this date Schouten's “Staaten Land” was found to be merely an inconsiderable island. Upon this discovery being announced, the country that Tasman had called Staaten Land received again the name of “New Zealand,” by which it has ever since been known. Tasman sailed along the coast to a bay, where he anchored. To this he gave the name of Murderers (now Massacre) Bay, on account of an unprovoked attack on a boat's crew by the natives, and the massacre of four white men. Thence he steered along the west coast of the North Island, and gave the name of Cape Maria van Diemen to the north-western extremity thereof. After sighting the islands of the Three Kings he finally departed, not having set foot in the country.

There is no record of any visit to New Zealand after Tasman's departure until the time of Captain Cook, who, after leaving the Society Islands, sailed in search of a southern continent then believed to exist. He sighted land on the 6th October, 1769, and on the 8th of that month cast anchor in Poverty Bay. After having coasted round the North Island and the Middle and Stewart Islands—which last he mistook for part of the Middle Island—he took his departure from Cape Farewell on the 31st March, 1770, for Australia. He visited New Zealand again in 1773, in 1774, and in 1777.

M. de Surville, a French officer in command of the vessel “Saint Jean Baptiste,” while on a voyage of discovery, sighted the northeast coast of New Zealand on the 12th December, 1769, and remained for a short time. A visit was soon after paid by another French officer, M. Marion du Fresne, who arrived on the west coast of New Zealand on the 24th March, 1772, but was treacherously murdered by the Natives on the 12th June following.

In 1793 the “Dædalus,” under the command of Lieutenant Hanson, was sent by the Government of New South Wales to New Zealand, and two chiefs were taken thence to Norfolk Island. There was after this an occasional intercourse between the islands of New Zealand and the English settlements in New South Wales.

In 1814 the first missionaries arrived in New Zealand—Messrs. Hall and Kendall—who had been sent as forerunners to Mr. Marsden. After a short stay they returned to New South Wales, and on the 19th November of that year again embarked in company with Mr. Marsden, who preached his first sermon in New Zealand on Christmas Day, 1814, and returned to Sydney on the 23rd March, 1815. Six years later, in 1821, the work of evangelization was put on a somewhat permanent basis; but the first station, established by Mr. Leigh, a Wesleyan missionary, and his wife, at the valley of the Kaeo, Whangaroa, was not taken possession of until the 10th June, 1823.

Prior to the colonisation of New Zealand by Europeans, the earliest navigators and explorers found a race of people already inhabiting both islands. Papers written in 1874 by Mr. (afterwards Sir) William Fox, and Sir Donald McLean, then Native Minister, state that at what time the discovery of these islands was made by the Maoris, or from what place they came, are matters lost in the obscurity enveloping the history of a people without letters. Nor is there anything on record respecting the origin of the Maori people themselves. Little more can now be gathered from their traditions than that they were immigrants, and that when they came there were probably no other inhabitants of the country. The tradition runs that, generations ago, the Maoris dwelt in a country named Hawaiki, and that one of their chiefs was driven thence by a storm, and, after a long voyage, fetched the northern island of New Zealand. Returning to his home with a flattering description of the country he had discovered, this chief, it is said, persuaded a number of his followers to join him, and with a large fleet of double canoes started for the new land. The names of most of the canoes are still remembered, and each tribe agrees in its account of the doings of the people of the principal canoes after their arrival in New Zealand; and from these traditional accounts the descent of the numerous tribes has been traced. Calculations, based on the genealogical staves kept by the tohungas, or priests, indicate that about twenty-seven generations have passed since the migration, which may therefore be assumed to have taken place about six hundred and seventy years ago. The locality of the legendary Hawaiki is unknown, but many places in the South Seas have been thus named in memory of the mother-land. The Maoris speak a very pure dialect of the Polynesian language, the common tongue, with more or less variation, in all the Eastern Pacific Islands. When Captain Cook first visited New Zealand he availed himself of the services of a native from Tahiti, whose speech was easily understood by the Maoris. In this way much information respecting the early history of the country and its inhabitants was obtained which could not have otherwise been had.

A special article will be found further on dealing with the subject of the numbers and present condition of the Maoris.

The first attempt at colonisation was made in 1825 by a company formed in London. An expedition was sent out under the command of Captain Herd, who bought two islands in the Hauraki Gulf and a strip of land at Hokianga. The attempt, however, was a failure, owing to the savage character of the inhabitants. In consequence of frequent visits of whaling-vessels to the Bay of Islands, a settlement grew up at Kororareka—now called Russell—and in 1833 Mr. Busby was appointed British Resident there. A number of Europeans—generally men of low character—gradually settled in different parts of the country, and married Native women.

In 1838 a colonisation company, known as the New Zealand Company, was formed to establish settlement on systematic principles. A preliminary expedition, under the command of Colonel William Wakefield, was despatched from England on the 12th May, 1839, and arrived in New Zealand in the following August. Having purchased land from the Natives, Colonel Wakefield selected the shore of Port Nicholson, in Cook Strait, as the site of the first settlement. On the 22nd January, 1840, the first body of immigrants arrived, and founded the town of Wellington. About the same time—namely, on the 29th January, 1840—Captain Hobson, R.N., arrived at the Bay of Islands, empowered, with the consent of the Natives, to proclaim the sovereignty of the Queen over the islands of New Zealand, and to assume the government thereof. A compact called “The Treaty of Waitangi,” to which in less than six months five hundred and twelve names were affixed, was entered into, whereby all rights and powers of sovereignty were ceded to the Queen, all territorial rights being secured to the chiefs and their tribes. New Zealand was then constituted a dependency of the Colony of New South Wales, but on the 3rd May, 1841, was proclaimed a separate colony. The seat of Government had been previously established at Waitemata (Auckland), round which a settlement was formed.

The New Zealand Company having decided to form another settlement, to which the name of “Nelson” was to be given, despatched a preliminary expedition from England in April, 1841, for the purpose of selecting a site, which resulted in the establishment of the settlement at the head of Blind Bay. About the same time a number of pioneers arrived in Taranaki, despatched thither by the New Plymouth Company, a colonising society which had been formed in England, and had bought 50,000 acres of land from the New Zealand Company.

The next important event in the progress of colonisation was the arrival at Port Chalmers, in March, 1848, of two emigrant ships sent out by the Otago Association for the foundation of a settlement by persons belonging to or in sympathy with the Free Church of Scotland.

In 1849 the “Canterbury Association for founding a Settlement in New Zealand” was incorporated. On the 16th December, 1850, the first emigrant ship despatched by the association arrived at Port Cooper, and the work of opening up the adjoining country was set about in a systematic fashion, the intention of the promoters being to establish a settlement complete in itself, and composed entirely of members of the then United Church of England and Ireland.

The Proclamation of Captain Hobson on the 30th January, 1840, gave as the boundaries of the colony the following degrees of latitude and longitude: On the north, 34° 30′ S. lat.; on the south, 47° 10′ S. lat.; on the east, 179° 0′ E. long.; on the west, 166° 5′ E. long. These limits excluded small portions of the extreme north of the North Island and of the extreme south of Stewart Island.

In April, 1842, by Royal Letters Patent, and again by the Imperial Act 26 and 27 Vict., c. 23 (1863), the boundaries of the colony were altered so as to extend from 33° to 53° of south latitude and from 162° of east longitude to 173° of west longitude. By Proclamation bearing date the 21st July, 1887, the Kermadec Islands, lying between the 29th and 32nd degrees of south latitude and the 177th and 180th degrees of west longitude, were declared to be annexed to and to become part of the Colony of New Zealand.

The following now constitute the Colony of New Zealand:—

The island commonly known as the North Island, with its adjacent islets, having an aggregate area of 44,468 square miles, or 28,459,580 acres.

The island known as the Middle Island, with adjacent islets, having an aggregate area of 58,525 square miles, or 37,456,080 acres.

The South or Stewart Island, and adjacent islets, having an area of 665 square miles, or 425,390 acres.

The Chatham Islands, situate 536 miles eastward of Lyttelton, in the Middle Island, with an area of 375 square miles, or 239,920 acres.

The Auckland Islands, about 200 miles south of Stewart Island, extending about 30 miles from north to south, and nearly 15 from east to west, the area being 210,650 acres.

The Campbell Islands, in latitude 52° 33′ south, and longitude 169° 8′ west, about 30 miles in circumference, with an area of 45,440 acres.

The Antipodes Islands, about 458 miles in a south-easterly direction from Port Chalmers, in the Middle Island. These are-detached rocky islands, and extend over a distance of between 4 and 5 miles from north to south. Area, 12,960 acres.

The Bounty Islands, a small group of islets, thirteen in number, lying north of the Antipodes Islands, and about 415 miles in an east-south-easterly direction from Port Chalmers. Area, 3,300 acres.

The Kermadec Islands, a group lying about 614 miles to the north-east of Russell, in the Bay of Islands. Raoul or Sunday Island, the largest of these, is about 20 miles in circuit. The next in size is Macaulay Island, about 3 miles round. Area of the group, 8,208 acres.

The total area of the colony is thus about 104,471 square miles, of which the aggregate area of the outlying groups of islands that are practically useless for settlement amounts to about 438 square miles.

A protectorate is exercised by the Imperial Government over the Cook Islands (or Hervey Group) by Proclamation dated the 27th October, 1888. The British Resident* is appointed on the recommendation of the New Zealand Government. He acts as Government Agent for the colony in all matters of trade.

* Frederick J. Moss, Esq., late M.H.R., is now British Resident. His salary is paid by this colony.

The areas of the several Australian Colonies, as given by different authorities, vary considerably. The total area of the Australian Continent is given as 2,944,628 square miles, according to a computation made by the late Surveyor-General of Victoria, Mr. J. A. Skene, from a map of Continental Australia compiled and engraved under his direction; but the following areas are taken from the official records of each colony:—

| Square Miles. | |

|---|---|

| Queensland | 668,497 |

| New South Wales | 310,700 |

| Victoria | 87,884 |

| South Australia | 903,425 |

| Western Australia | 1,060,000 |

| Total Continent of Australia | 3,030,506 |

| Tasmania | 26,215 |

| New Zealand (including the Chatham and other islands) | 104,471 |

| Total Australasia | 3,161,192 |

The size of these colonies may be better realised by comparison of their areas with those of European countries. The areas of the following countries—Austria - Hungary, Germany, France, Belgium, Holland, Denmark, Sweden and Norway, Portugal, Spain, Italy (including Sardinia and Sicily), Switzerland, Greece, Roumania, Bulgaria, Servia, Eastern Roumelia, and Turkey in Europe—containing on the whole rather less than 1,600,000 square miles, amount to little more than half the extent of the Australian Continent. If the area of Russia in Europe be added to those of the other countries the total would be about one-seventh larger than the Australian Continent, and about one-twelfth larger than that of the Australasian Colonies, including New Zealand.

The area of the Colony of New Zealand is little more than one-seventh less than the area of Great Britain and Ireland, that of the Middle Island of New Zealand being a little larger than the combined areas of England and Wales.

| United Kingdom. | Area in Square Miles. |

|---|---|

| England and Wales | 58,311 |

| Scotland | 30,463 |

| Ireland | 32,531 |

| Total | 121,305 |

| New Zealand. | Area in Square Miles. |

|---|---|

| North Island | 44,468 |

| Middle Island | 58,525 |

| Stewart Island | 665 |

| Chatham Islands | 375 |

| Other islands | 438 |

| Total | 104,471 |

The North Island extends over a little more than seven degrees of latitude—a distance in a direct line from north to south of 430 geographical or 498 statute miles; but, as the northern portion of the colony, which covers more than three degrees of latitude, trends to the westward, the distance in a straight line from the North Cape to Cape Palliser, the extreme northerly and southerly points of the island, is about 515 statute miles.

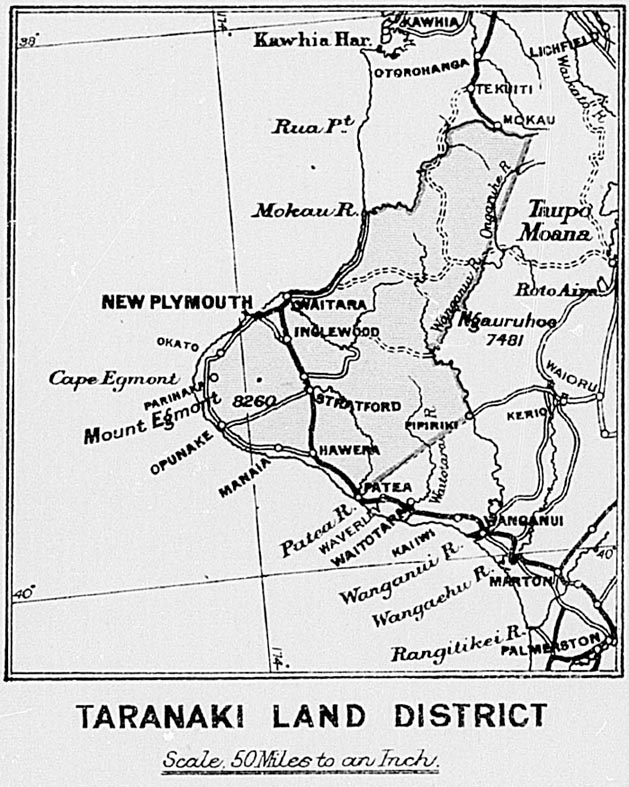

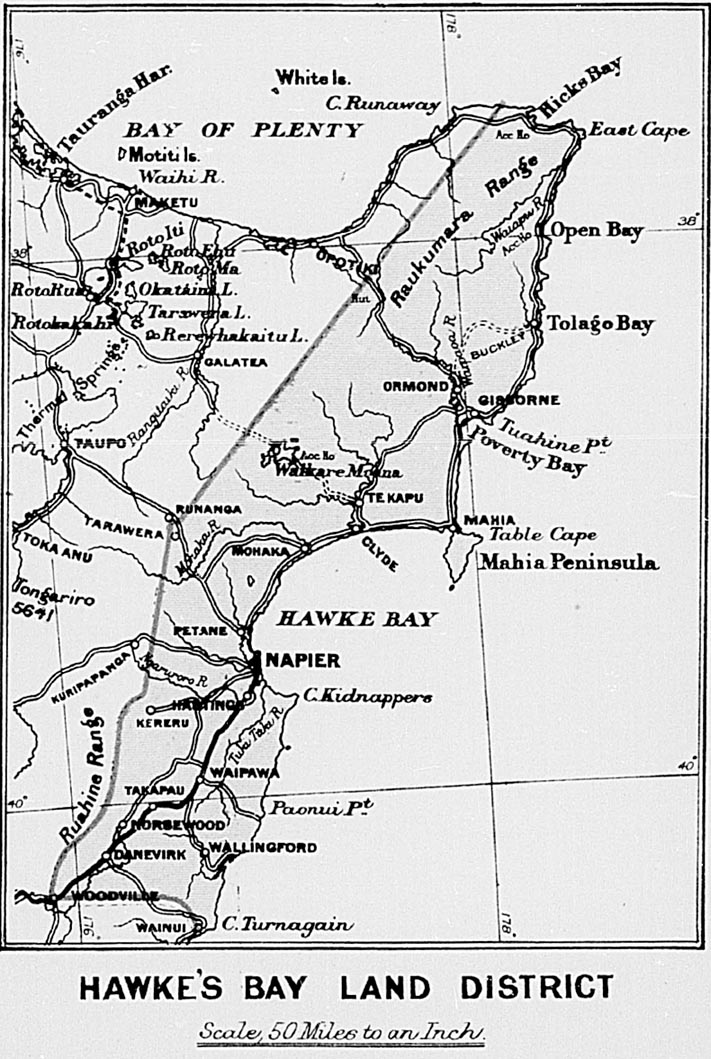

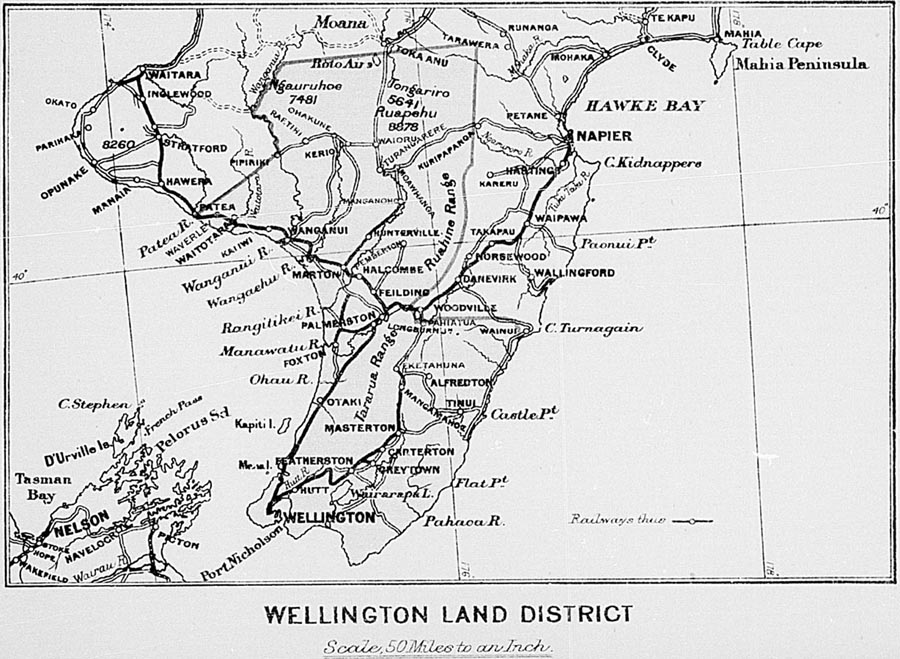

This island is, as a whole, hilly, and, in parts, mountainous in character, but there are large areas of plain or comparatively level country that are, or by clearing may be made, available for agricultural purposes. Of these, the principal are the plains in Hawke's Bay on the East Coast, the Wairarapa Plain in the Wellington District, and a strip of country along the West Coast, about 250 miles in length, extending from a point about thirty miles from the City of Wellington to a little north of New Plymouth. The largest plain in the North Island, Kaingaroa, extends from the shore of Lake Taupo in a north-north-easterly direction to the sea-coast in the Bay of Plenty; but a large portion is covered with pumice-sand, and is unfitted for tillage or pasture. There are several smaller plains and numerous valleys suitable for agriculture; The level or undulating country in this island fit, or capable of being made fit, for agriculture has been roughly estimated at 13,000,000 acres. This includes lands now covered with standing forest, and swamps that are capable of drainage; also large areas of clay-marl and pumice-covered land. The clay-marl in its natural state is cold and uninviting to the farmer, but under proper drainage and cultivation it can be brought to a high state of productiveness. This kind of land is generally neglected at the present time, as settlers prefer soils more rapidly remunerative and less costly to work. The larger portion of the North Island was originally covered with forest. Although the area of bush-land is still very great, yet year by year the amount is being reduced, chiefly to meet; the requirements of settlement, the trees being cut down and burnt, and grass-seed sown on the ashes to create pasture. Hilly as the country is, yet from the nature of the climate it is especially suited for the growth of English grasses, and wherever there is any soil, however steep the land may be, grasses will flourish; consequently very little of the land is unfit to supply food for cattle and sheep when treated as above or otherwise laid down in grass. The area of land in the North Island deemed purely pastoral or capable of being made so, while too steep for agricultural purposes, is estimated at 14,200,000 acres. In the centre of the island is a lake, about twenty miles across either way from the extreme points, called Taupo. A large area adjacent to the lake is at present worthless pumice-country. The Waikato River, the largest in the North Island, flows out of its north-eastern point, and runs thence north-westward until it flows into the ocean a little distance south of the Manukau Harbour. This river is navigable for small steamers for about a hundred miles from its mouth. The Maori King country, occupied by Natives who for several years isolated themselves from the Europeans, lies between Lake Taupo and the western coast. The River Thames, or Waihou, having its sources north of Lake Taupo, flows northward into the Firth of Thames. It is navigable for small steamers only for about fifty miles. The other navigable rivers in this island are the Wanganui and Manawatu, which flow towards the south-west into Cook Strait.

The mountains in the North Island are estimated to occupy about one-tenth of the surface, and do not exceed 4,000ft. in height, with the exception of a few volcanic mountains that are more lofty. Of these, the three following are the most important:—

The Tongariro Mountain, situated to the southward of Lake Taupo. It consists of a group of distinct volcanic cones, the lava-streams from which have so overlapped in their descent as to form one compact mountain-mass at the base. The highest of these cones is called Ngauruhoe, and attains an elevation of 7,515ft. The craters of Ngauruhoe, the Red Crater (6,140ft.), and Te Mari (4,990ft.) are the three vents from which the latest discharges of lava have taken place, the most recent having occurred in 1868. These craters are still active, steam and vapour issuing from them with considerable force and noise, the vapours being charged with pungent gases and acids, making it dangerous to approach too near the crater-lips.

Ruapehu. This mountain lies to the south of Tongariro. It is an extinct volcanic cone, and reaches the height of 9,100ft., being in part considerably above the line of perpetual snow. The most remarkable feature of this mountain is the crater-lake on its summit. This lake lies at the bottom of a funnel-shaped crater, the steep sides of which are mantled with ice and snow. The water occupies a circular basin about 500ft. in diameter, and is about 300ft. below the enclosing peaks, and quite inaccessible except by ropes. It is much disturbed by eddies, from which steam or vapour is given off. This lake, and the three craters previously mentioned on Tongariro, are all in one straight line, which, if produced, would pass through the boiling springs at Tokaanu on the southern margin of Lake Taupo, the volcanic country north-east of that lake, and White Island, an active volcano in the Bay of Plenty, situated about twenty-seven miles from the mainland.

Mount Egmont. This is also an extinct volcanic cone, rising to a height of 8,300ft. The upper part is always covered with snow. This mountain is situated close to New Plymouth, and is surrounded by one of the most fertile districts in New Zealand. Rising from the plains in its solitary grandeur, it is an object of extreme beauty, the cone being one of the most perfect in the world.

It is estimated that the area of mountain-tops and barren country at too high an altitude for sheep, and therefore worthless for pastoral purposes, amounts, in the North Island, to 300,000 acres.

Without a doubt the hot springs form the most remarkable feature of the North Island. They are found over a large area, extending from Tongariro, south of Lake Taupo, to Ohaeawai, in the extreme north—a distance of some 300 miles; but the principal seat of hydrothermal action appears to be in the neighbourhood of Lake Rotorua, about forty miles north-north-east from Lake Taupo. By the destruction of the famed Pink and White Terraces and of Lake: Rotomahana during the eruption of Mount Tarawera on the 10th June, 1886, the neighbourhood has been deprived of attractions unique in character and of unrivalled beauty; but the natural features of the country—the lakes, geysers, and hot springs, the number of which is very great, and some of which possess remarkable curative properties for certain complaints—still afford considerable attraction for tourists and invalids. Recently the world-wide importance of conserving this region as a sanatorium for all time has been recognised by the Government, and it is now dedicated by Act of Parliament to that purpose.

Notwithstanding the length of coast-line, good harbours in the North Island are not numerous. Those on the west coast north of New Plymouth are bar-harbours, not suitable for large vessels. The principal harbours are the Waitemata Harbour, on which Auckland is situated—this is rather a deep estuary than a harbour; several excellent havens in the northern peninsula; and Port Nicholson, on the borders of which Wellington is situated. This is a landlocked harbour, about six miles across, having a comparatively narrow but deep entrance from the ocean. The water is deep nearly throughout.

Cook Strait separates the North and Middle Islands. It is about sixteen miles across at its narrowest part, but in the widest about ninety. The strait is invaluable for the purpose of traffic between different parts of the colony.

The extreme length of the Middle Island, from Jackson's Head,’ in Cook Strait, to Puysegur Point, at the extreme south-west, is about 525 statute miles; the greatest distance across at any point is in Otago (the southernmost) District, being about 180 miles.

The Middle Island is intersected along almost its entire length by a mountainous range known as the Southern Alps. Some of the summits reach a height of from 10,000ft. to 12,000ft., Mount Cook, the highest peak, rising to 12,349ft.

In the south, in the neighbourhood of the sounds and Lake Te Anau, there are many magnificent peaks, which, though not of great height, are, owing to their latitude, nearly all crowned with perpetual ice and snow. Further north the mountains increase in height—Mount Earnslaw, at Lake Wakatipu; and Mount Aspiring, which has aptly been termed the New Zealand Matterhorn, nearly 10,000ft. in height, at Lake Wanaka. Northward beyond this a fine chain of peaks runs as the backbone of the Middle Island to where Mount Cook, or Aorangi, towers supreme in the midst of the grandest scenes of the Southern Alps.

For beauty and grandeur of scenery the Southern Alps of New Zealand may worthily compare with, while in point of variety they are said actually to surpass, the Alps of Switzerland. In New Zealand no one has actually succeeded in making a complete ascent of any of the highest mountains. Many of the peaks and most of the glaciers are as yet unnamed; and there is still, in parts of the Middle Island, a fine field for exploration and discovery—geographical, geological, and botanical. The wonders of the Southern Alps are only beginning to be known; but the more they are known the more they are appreciated. The snow-line in New Zealand being so much lower than in Switzerland, the scenery, though the mountains are not quite so high, is of surpassing grandeur.

There are extensive glaciers on both sides of the range, those on the west being of exceptional beauty, as, from the greater abruptness of the mountain-slopes on that side, they descend to within about 700ft. of the sea-level, and into the midst of the evergreen forest. The largest glaciers on each side of the range are easily accessible.

The following gives the sizes of some of the glaciers on the eastern slope:—

| Name. | Area of Glacier. | Length of Glacier. | Greatest Width. | Average Width. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acres. | Miles | ch. | Miles | ch. | Miles | ch. | |

| Tasman | 13,664 | 18 | 0 | 2 | 14 | 1 | 15 |

| Murchison | 5,800 | 10 | 70 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 66 |

| Godley | 5,312 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 55 | 1 | 3 |

| Mueller | 3,200 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 61 | 0 | 50 |

| Hooker | 2,416 | 7 | 25 | 0 | 54 | 0 | 41 |

The Alletsch Glacier in Switzerland, according to Ball, in the “Alpine Guide,” has an average width of one mile. It is in length and width inferior to the Tasman Glacier.

Numerous sounds or fiords penetrate the south-western coast. They are long, narrow, and deep (the depth of water at the upper part of Milford Sound is 1,270ft., although at the entrance only 130ft.), environed by giant mountains clothed with foliage to the snow-line, with waterfalls, glaciers, and snowfields at every turn. Some of the mountains rise almost precipitously from the water's edge to 5,000ft. and 6,000ft. above the sea. Near Milford, the finest of these sounds, is the great Sutherland Waterfall, 1,904ft. high.

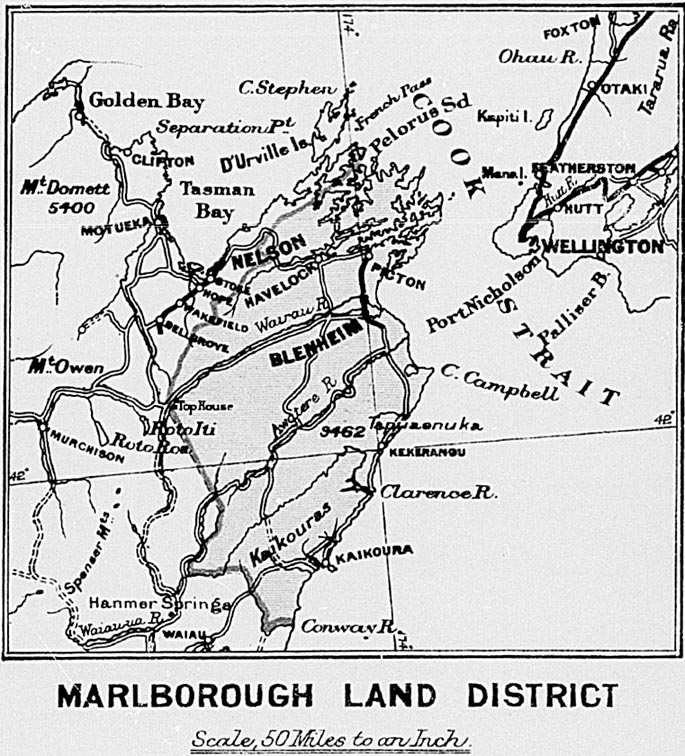

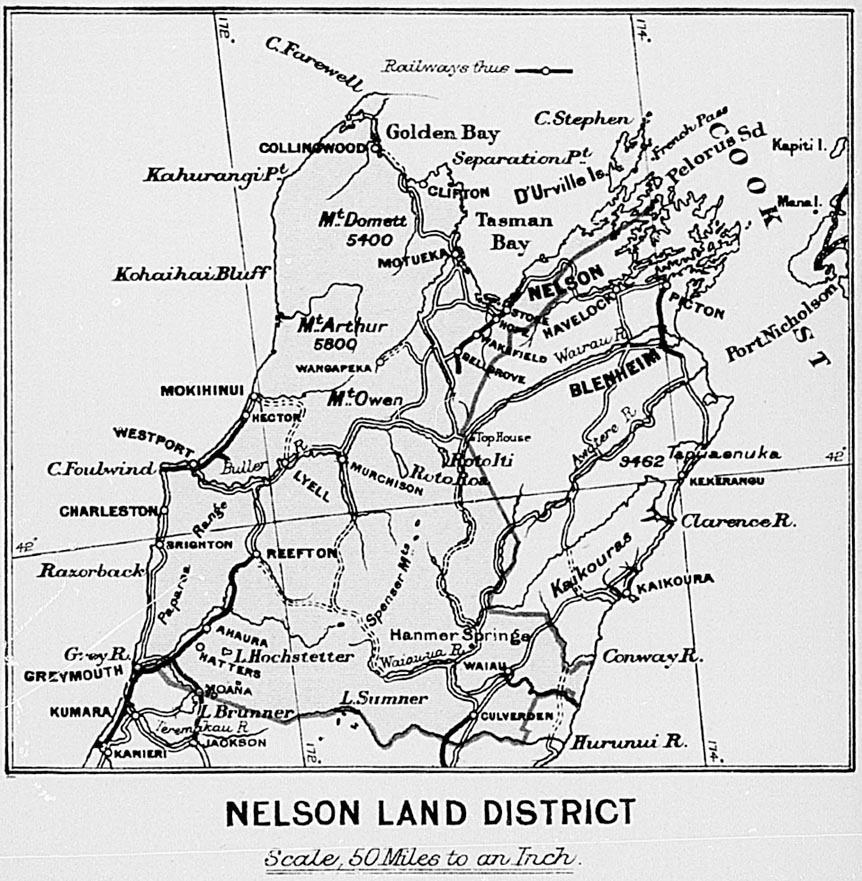

The general surface of the northern portion of the Middle Island, comprising the Provincial Districts of Nelson and Marlborough, is mountainous, but the greater part is suitable for grazing purposes. There are some fine valleys and small plains suitable for agriculture, of which the Wairau Valley or Plain is the largest. Deep sounds, extending for many miles, break the coast-line abutting on Cook Strait. The City of Nelson is situated at the head of Blind Bay, which has a depth inwards from Cook Strait of about forty statute miles.

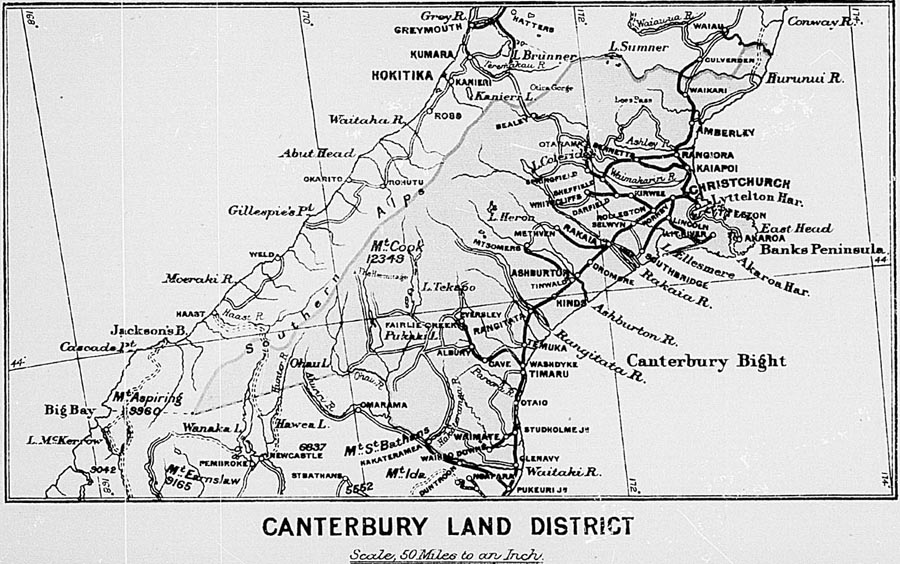

The Provincial District of Canterbury lies to the south of the Marlborough District, and on the eastern side of the island. Towards the north the land is undulating; then there is a stretch of almost perfectly level country extending towards the south-west 160 miles, after which, on the south, the country is undulating as far as the borders of the Otago District. On the east a block of hill-country rises abruptly from the plain and extends for some miles seaward. This is Banks Peninsula, containing several good harbours, the principal being Port Cooper, on the north, on which is situated Lyttelton, the chief port of the district: the harbour of Akaroa, considered one of the finest in the colony, is on the southern coast of this peninsula.

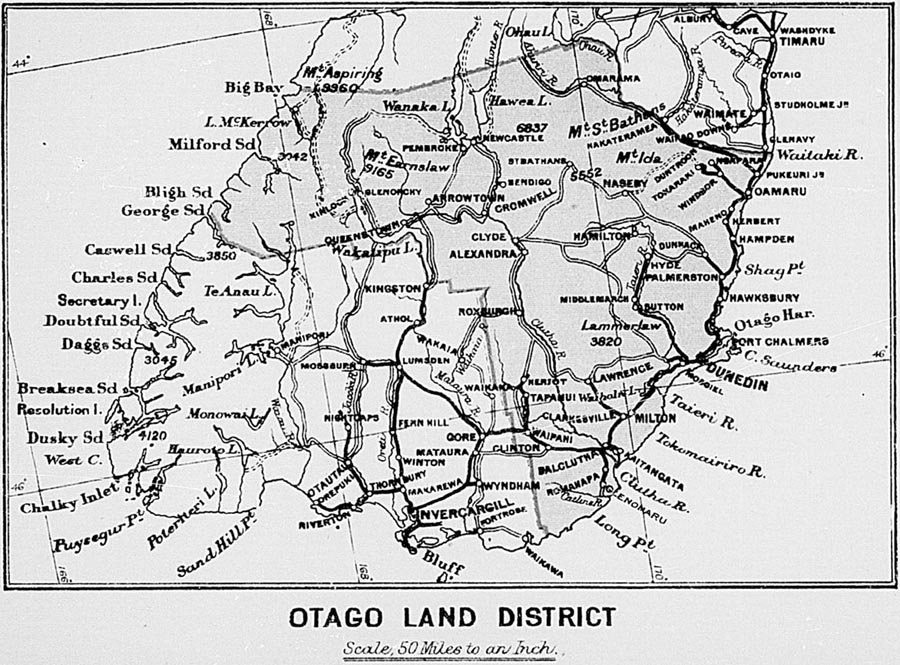

The District of Otago is, on the whole, mountainous, but has many fine plains and valleys suitable for tillage. The mountains, except towards the west coast, are generally destitute of timber, and are suitable for grazing sheep. There are goldfields of considerable extent in the interior of this district. The inland lakes are very important features in Otago. Lake Wakatipu extends over fifty-four miles in length, but its greatest width is not more than four miles. It is 1,070ft. above sea-level, and has a depth varying from 1,170ft. to 1,296ft. It covers an area of 114 square miles. Te Anau Lake is still larger, having an area of 132 square miles. These lakes are bounded on the west by broken, mountainous, and wooded country, extending to the ocean.

The chief harbours in Otago are Port Chalmers, at the head of which Dunedin is situated, and the Bluff Harbour, at the extreme south.

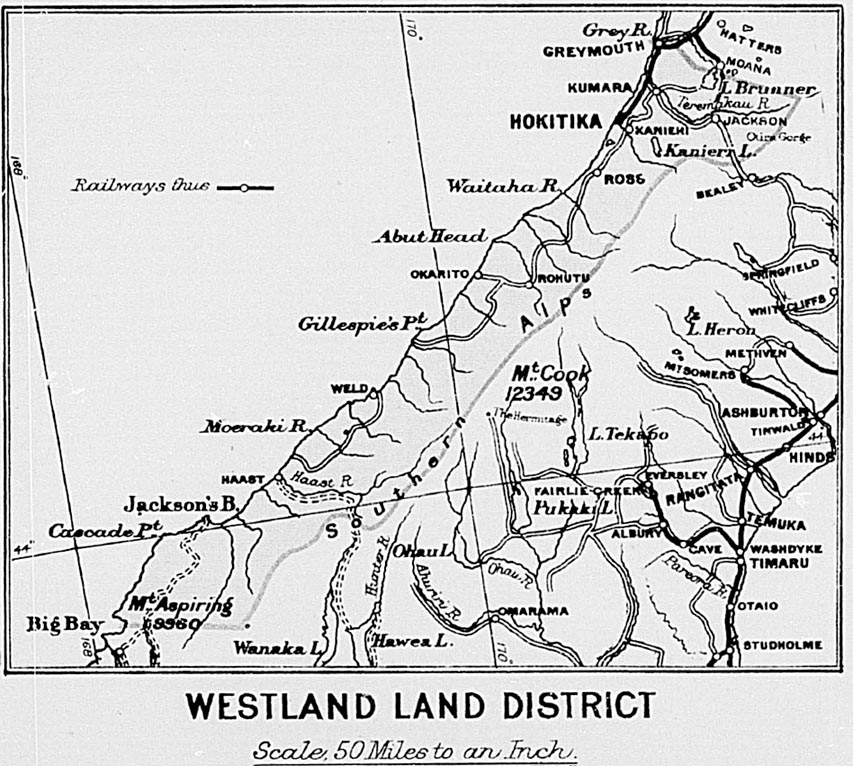

The District of Westland, extending along the west coast of the Middle Island, abreast of Canterbury, is more or less auriferous throughout. The western slopes of the central range of mountains are clothed with forest-trees to the snow-line; but on the eastern side timber is scarce, natural grasses covering the ground.

The rivers in the Middle Island are for the most part mountain-torrents, fed by glaciers in the principal mountain-ranges. When the snow melts they rise in flood, forming, where not confined by rocky walls, beds of considerable width, generally covered by enormous deposits of shingle. The largest river in the colony as regards volume of water is the Clutha. It is 154 miles in length, but is only navigable for boats or small river-steamers for about thirty miles. The Rivers Buller, Grey, and Hokitika, on the West Coast, are navigable for a short distance from their mouths. They form the only ports in the Westland District. In their unimproved state they admitted, owing to the bars at their mouths, none but vessels of small draught; but, in consequence of the importance of the Grey and Buller Rivers as the sole ports available for the coal-export trade, large harbour-works have been undertaken, resulting in the deepening of the beds of these rivers, and giving a depth of from 18ft. to 24ft. of water on the bars.

The area of level or undulating land in the Middle Island that may be available for agriculture is estimated at about 15,000,000 acres. About 13,000,000 are suitable for pastoral purposes only, or may become so when cleared of forest and sown with grass-seed. The area of barren land and mountain-tops is estimated at about 8,000,000 acres.

Foveaux Strait separates the Middle from Stewart Island. This last island has an area of only 425,390 acres. It is mountainous, and for the most part covered with forest.

The outlying group of the Chatham Islands, 480 statute miles east-south-east from Wellington, and 536 miles eastward of Lyttelton, consists of. two principal islands and several unimportant islets. The largest island contains about 222,490 acres, of which an irregularly-shaped lake or lagoon absorbs 45,960 acres About one-quarter of the surface of the land is covered with forest, the rest with fern or grass. The hills nowhere rise to a great height. Pitt Island is the next in size; the area is 15,330 acres. The greater portion of both islands is used for grazing sheep.

The Kermadec group of islands, four in number, are situated between 29° 10′ and 31° 30′ south latitude, and between 177° 45′ and 179° west longitude. They are named Raoul or Sunday Island, Macaulay Island, Curtis Island, and L'Espérance or French Rock. The principal island, Sunday, is 600 miles distant from Auckland. The islands are volcanic, and in two of them signs of activity are still to be seen. The rainfall is plentiful, but not excessive. The climate is mild and equable, and slightly warmer than the north of New Zealand. The following are the areas of the islands and islets of the group: Sunday Island, 7,200 acres; Herald group of islets, 85 acres; Macaulay Island, 764 acres; Curtis Islands, 128 acres and 19 acres; L'Espérance, 12 acres: total, 8,208 acres. Sunday Island is twenty miles in circumference, roughly triangular in shape, and at the highest point 1,723ft. above the sea-level. It is rugged and broken over a very large extent of its surface, and, except in a few places, covered with forest. The soil everywhere on the island is very rich, being formed by the decomposition of a dark-coloured pumiceous tuff and a black andesitic lava, with which is closely mixed a fine vegetable mould. The great luxuriance and richness of the vegetation bear witness to the excellence of the soil, which is everywhere—except where destroyed by eruptions, and on the steep cliffs—the same rich loam. Want of water is one of the drawbacks. Three of the four lakes on the island are fresh, but so difficult of approach as to be practically useless.

The Auckland Islands are about 290 miles south of Bluff* Harbour, their position being given on the Admiralty chart as latitude 50° 31′ 29” S., and longitude 166° 19′ 12” E. They have several good harbours. Port Boss, at the north end of the principal island, was described by the eminent French commander, D'Urville, as one of the best harbours of refuge in the known world. At the southern end’ of the island there is a through passage extending from the east to the west coast. It has been variously named Adam's Strait or Carnley Harbour, and forms a splendid sheet of water. The largest of the islands is about 27 miles long by about 15 miles broad, and is very mountainous, the highest part being about 2,000ft. above the sea. The west coast is bold and precipitous, but the east coast has several inlets. The wood on the island is, owing to the strong prevailing wind, scrubby in character. The New Zealand Government maintains at this island a depot of provisions and clothing for the use of shipwrecked mariners.

British sovereignty was proclaimed over New Zealand in January, 1840, and the country became a dependency of New South Wales until the 3rd May, 1841, when it was made a separate colony. The seat of Government was at Auckland, and the Executive included the Governor, and three gentlemen holding office as Colonial Secretary, Attorney-General, and Colonial Treasurer.

The successors of these gentlemen, appointed in August, 1841, May, 1842, and January, 1844, respectively, continued in office until the establishment of Responsible Government on the 7th May, 1856. Only one of them—Mr. Swainson, the Attorney-General—sat as a member of the first General Assembly, opened on the 27th May, 1854. During the session of that year there were associated with the permanent members of the Executive Council certain members of the General Assembly. These latter held no portfolios.

The Government of the colony was at first vested in the Governor, who was responsible only to the Crown; but in 1852 an Act granting representative institutions to the colony was passed by the Imperial Legislature. Under it the constitution of a General Assembly for the whole colony was provided for, consisting of a Legislative Council, the members of which were to be nominated by the Governor, and an elective House of Representatives. The first session of the General Assembly was opened on the 27th May, 1854, but the members of the Executive were not responsible to Parliament. The first Ministers under a system of Responsible Government were appointed on the 18th April, 1856. By the Act of 1852 the colony was divided into six provinces, each to be presided over by an elective Superintendent, and to have an elective Provincial Council, empowered to legislate, except on certain specified subjects. The franchise amounted practically to household suffrage. In each case the election was for four years; but a dissolution of the Provincial Council by the Governor could take place at any time, necessitating a fresh election both of the Council and of the Superintendent. The Superintendent was chosen by the whole body of electors of the province; the members of the Provincial Council by those of the electoral districts. The Provincial Governments, afterwards increased to nine, remained as integral parts of the Constitution of the colony until the 1st November, 1876, when they were abolished by an Act of the General Assembly, that body having been vested with the power of altering the Constitution Act. On the same day an Act of the General Assembly which subdivided the colony (exclusive of the areas included within municipalities) into counties, and established a system of local county government, came into operation.

The Governor is appointed by the Queen. His salary is £5,000 a year, and is provided by the colony.

Members of the Legislative Council hold their seats under writs of summons from the Governor. Till the year 1891 the appointments were for life; but in September of that year an Act was passed making such appointments after that time tenable for seven years only, though Councillors may be reappointed. In either case seats may be vacated by resignation or extended absence. Two members of the Council are aboriginal native chiefs.

The members of the House of Representatives are elected for three years from the time of each general election; but at any time the dissolution of Parliament by the Governor may necessitate such general election. Four of the members are representatives of Native constituencies. An Act was passed in 1887 which provided that, on the termination of the then General Assembly, the number of members to be thereafter elected to the House of Representatives should be seventy-four in all, of whom four were to be elected, under the provisions of the Maori Representation Acts, as representatives of Maori electors only. For the purposes of European representation the colony is divided into sixty-two electoral districts, four of which—the Cities of Auckland, Wellington, Christ-church, and Dunedin—return each three members, and all the other electorates one each. Members of the House of Representatives are chosen by the votes of the inhabitants in every electoral district appointed for that purpose.

In 1889 an amendment of the Representation Act was passed, which contained a provision prohibiting any elector from giving his vote in respect of more than one electorate at any election. “The Electoral Act, 1893,” has extended to women of both races the right to register as electors, and to vote at the elections for members of the House of Representatives. The qualification for registration is the same for both sexes, and remains, under the Act of 1893, substantially unaltered. No person is entitled to be registered on more than one electoral roll within the colony, whatever the number or nature of the qualifications he or she may possess, or wherever they may be. Women are not qualified to be elected as members of the House of Representatives. The changes in the electoral laws, with remarks on the results of the election of November, 1893, are the subject of a special article in Part III. of this work. Every man registered as an elector, and not coming within the meaning of section 8 of “The Electoral Act, 1893,” is qualified to be elected a member of the House of Representatives for any electoral district. For European representation every adult person, if resident one year in the colony and three months in one electoral district, can be registered as an elector. Freehold property of the value of £25 held for six months preceding the day of registration also entitles a man or woman to register, if not already registered under the residential qualification. Maoris possessing a £25 freehold under Crown title can also register. For Maori representation every adult Maori resident in any Maori electoral district (of which there are four only in the colony) can vote. Registration is not required in Native districts. The proportion of representation to population at the last general election for the House of Representatives, in November, 1893, was one European member to every 9,603 inhabitants, and one Maori member to every 10,498 Natives.

Up to the year 1865 the seat of Government of New Zealand was at Auckland. Several attempts were made by members of Parliament, by motions in the Legislative Council and House of Representatives, to have it removed to some more central place; but it was not until November, 1863, that Mr. Domett (the then ex-Premier) was successful in carrying resolutions in the House of Representatives that steps should be taken for appointing some place in Cook Strait as the permanent seat of Government in the colony. The resolutions adopted were: “(1.) That it has become necessary that the seat of Government in the colony should be transferred to some suitable locality in Cook Strait. (2.) That, in order to promote the accomplishment of this object, it is desirable that the selection of the particular site in Cook Strait should be left to the arbitrament of an impartial tribunal. (3.) That, with this view, a Bill should be introduced to give effect to the above resolutions.” On the 25th November an address was presented to the Governor, Sir George Grey, K.C.B., by the Commons of New Zealand, requesting that the Governors of the Colonies of New South Wales, Victoria, and Tasmania might each be asked to appoint one Commissioner for the purpose of determining the best site in Cook Strait. Accordingly, the Hon. Joseph Docker, M.L.C., New South Wales; the Hon. Sir Francis Murphy, Speaker of the Legislative Council, Victoria; and R. C. Gunn, Esq., Tasmania, were appointed Commissioners.

These gentlemen, having made a personal inspection of all suitable places, arrived at the unanimous decision “that Wellington, in Port Nicholson, was the site upon the shores of Cook Strait which presented the greatest advantages for the administration of the government of the colony.”

The seat of Government was, therefore, in accordance with the recommendations of the Commissioners, removed to Wellington in February, 1865.

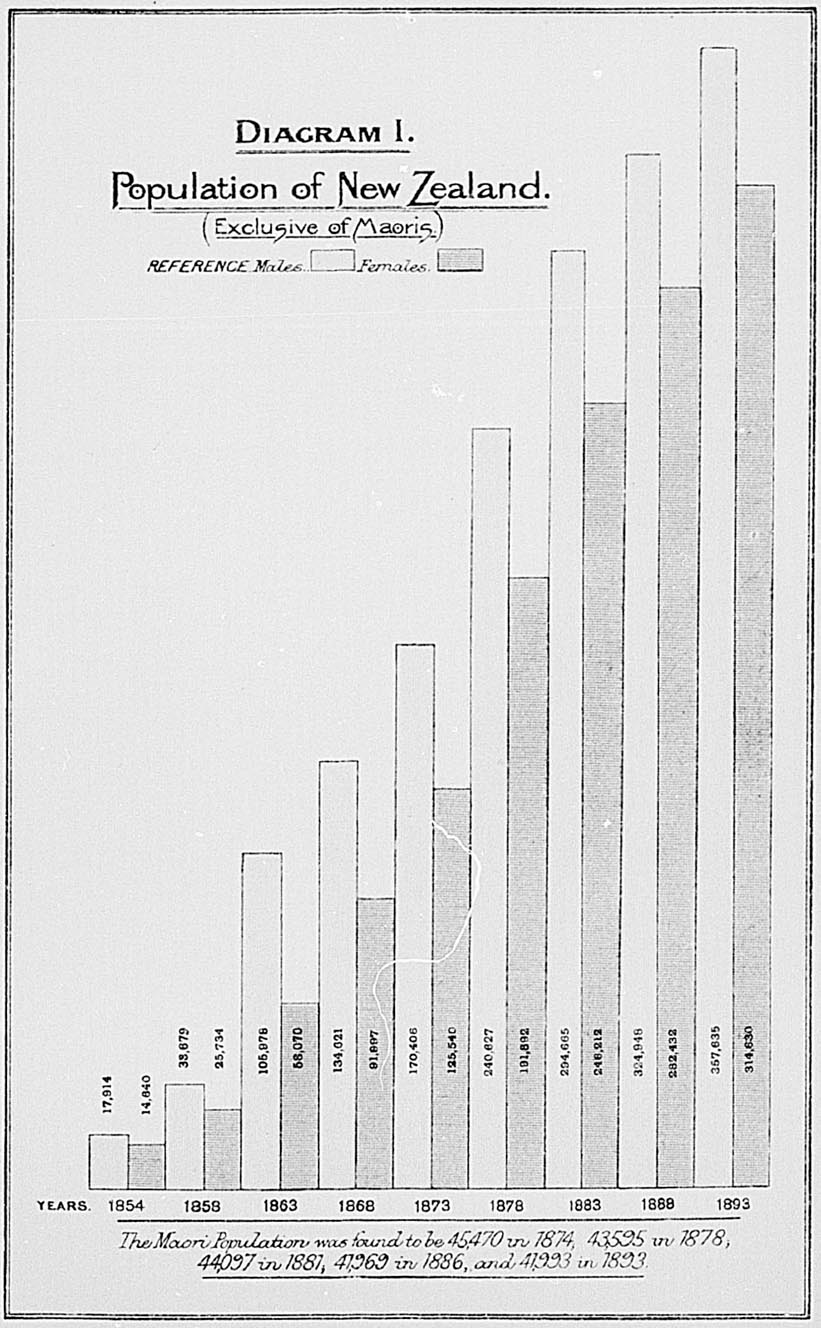

Nearly all the public works of New Zealand are in the hands of the Government of the colony, and in the early days they simply kept pace with the spread of settlement. In 1870, however, a great impetus was given to the progress of the whole country by the inauguration of the “Public Works and Immigration Policy,” which provided for carrying out works in advance of settlement. Railways, roads, and water-races were constructed, and immigration was conducted on a large scale. As a consequence, the population increased from 267,000 in 1871 to 501,000 in 1881, and 672,265 at the close of the year 1893, exclusive of Maoris.

SUCCESSIONOF GOVERNORSOF NEW ZEALAND, ANDTHE DATESONWHICHTHEYASSUMEDANDRETIREDFROMTHE GOVERNMENT.

Captain William Hobson, R.N., from Jan., 1840, to 10 Sept., 1842.

[British sovereignty was proclaimed by Captain Hobson in January, 1840, and New Zealand became a dependency of the Colony of New South Wales until 3rd May, 1841, at which date it was proclaimed a separate colony. From January, 1840, to May, 1841, Captain Hobson was Lieutenant-Governor of New Zealand under Sir George Gipps, Governor of New South Wales, and from May, 1841, Governor of New Zealand; the seat of Government being at Auckland, where he died in September, 1842. From the time of Governor Hobson's death, in September, 1842, until the arrival of Governor Fitzroy, in December, 1843, the Government was carried on by the Colonial Secretary, Lieutenant Shortland.]

Lieutenant Shortland, Administrator, from 10 Sept., 1842, to 26 Dec., 1843.

Captain Robert Fitzroy, R.N., from 26 Dec., 1843, to 17 Nov., 1845.

Captain Grey (became Sir George Grey, K.C.B., in 1848), from 18 Nov., 1845, to £31 Dec., 1853.

[Captain Grey held the commission as Lieutenant-Governor of the colony until the 1st January, 1848, when he was sworn in as Governor-in-Chief over the Islands of New Zealand, and as Governor of the Province of New Ulster and Governor of the Province of New Munster. After the passing of the New Zealand Constitution Act, Sir George Grey was, on the 13th September, 1852, appointed Governor of the colony, the duties of which office he assumed on the 7th March, 1853. In August, 1847, Mr. E. J. Eyre was appointed Lieutenant-Governor of New Munster: he was sworn in, 28th January, 1848. On 3rd January, 1848, Major- General George Dean Pitt was appointed Lieutenant-Governor of New Ulster: he was sworn in, 14th February, 1848; died, 8th January, 1851; and was succeeded as Lieutenant-Governor by Lieutenant-Colonel Wynyard, appointed 14th April, 1851; sworn in, 26th April, 1851. The duties of the Lieutenant-Governor ceased on the assumption by Sir George Grey of the office of Governor, on the 7th March, 1853.]

Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Henry Wynyard, C.B., Administrator, from 3 Jan., 1854, to 6 Sept., 1855.

Colonel Thomas Gore Browne, C.B., from 6 Sept., 1855, to 2 Oct., 1861.

Sir George Grey, K.C.B., Administrator, from 3 Oct., 1861; Governor, from 4 Dec., 1861, to 5 Feb., 1868.

Sir George Ferguson Bowen, G.C.M.G., from 5 Feb., 1868, to 19 Mar., 1873.

Sir George Alfred Arney, Chief Justice, Administrator, from 21 Mar. to 14 June, 1873.

Sir James Fergusson, Baronet, P.C., from 14 June, 1873, to 3 Dec., 1874.

The Marquis of Normanby, P.C., Administrator, from 3 Dec., 1874 Governor, from 9 Jan., 1875, to 21 Feb., 1879.

James Prendergast, Chief Justice, Administrator, from 21 Feb. to 27 Mar., 1879.

Sir Hercules George Robert Robinson, G.C.M.G., Administrator, 27 Mar., 1879; Governor, from 17 April, 1879, to 8 Sept., 1880.

James Prendergast, Chief Justice, Administrator, from 9 Sept. to 29 Nov., 1880.

Sir Arthur Hamilton Gordon, G.C.M.G., from 29 Nov., 1880, to 23 June, 1882.

Sir James Prendergast, Chief Justice, Administrator, from 24 June, 1882, to 20 Jan., 1883.

Lieutenant - General Sir William Francis Drummond Jervois, G.C.M.G., C.B., from 20 Jan., 1883, to 22 Mar., 1889.

Sir James Prendergast, Chief Justice, Administrator, from 23 Mar. to 2 May, 1889.

The Earl of Onslow, G.C.M.G., from 2 May, 1889, to 24 Feb., 1892.

Sir James Prendergast, Chief Justice, Administrator, from 25 Feb. to 6 June, 1892.

The Earl of Glasgow, G.C.M.G., from 7 June, 1892.

MEMBERSOFTHE EXECUTIVE COUNCILOFTHE COLONYOF NEW ZEALANDPREVIOUSTOTHE ESTABLISHMENTOF RESPONSIBLE GOVERNMENT (NOTINCLUDINGTHE OFFICERS COMMANDINGTHE FORCES).

Willoughby Shortland, Colonial Secretary, from 3 May, 1841, to 31 Dec., 1843; succeeded by Mr. Sinclair.

Francis Fisher, Attorney-General, from 3 May to 10 Aug., 1841; succeeded by Mr. Swainson.

George Cooper, Colonial Treasurer, from 3 May, 1841, to 9 May, 1842; succeeded by Mr. Shepherd.

William Swainson, Attorney-General, from 10 Aug., 1841, to 7 May, 1856.

Alexander Shepherd, Colonial Treasurer, from 9 May, 1842, to 7 May, 1856.

Andrew Sinclair, Colonial Secretary, from 6 Jan., 1844, to 7 May, 1856.

[The three gentlemen last mentioned were nominated by Her Majesty as ex officio members of the Executive Council. Two of them, the Colonial Secretary and the Colonial Treasurer, were not members of the General Assembly, opened for the first time 27th May, 1854, but all three remained in office until the establishment of Responsible Government.]

James Edward FitzGerald, M.H.R., without portfolio, from 14 June to 2 Aug., 1854.

Henry Sewell, M.H.R., without portfolio, from 14 June to 2 Aug., 1854.

Frederick Aloysius Weld, M.H.R., without portfolio, from 14 June to 2 Aug., 1854.

Francis Dillon Bell, M.L.C., without portfolio, from 30 June to 11 July, 1854.

Thomas Houghton Bartley, M.L.C., without portfolio, from 14 July to 2 Aug., 1854.

Thomas Spencer Forsaith, M.H.R., without portfolio, from 31 Aug. to 2 Sept., 1854.

Edward Jerningham Wakefield, M.H.R., without portfolio, from 31 Aug. to 2 Sept., 1854.

William Thomas Locke Travers, M.H.R., without portfolio, 31 Aug. to 2 Sept., 1854.

James Macandrew, M.H.R., without portfolio, from 31 Aug. to Sept., 1854.

NUMBEROF PARLIAMENTSSINCETHE CONSTITUTION ACTPASSEDFORCONFERRING REPRESENTATIVE INSTITUTIONSUPONTHE COLONYOF NEW ZEALAND, WITHTHE DATESOF OPENINGOF SESSIONSAND DATESOF CLOSINGOR DISSOLUTION.

| No. of Parliament. | Date of Opening of Sessions. | Date of Closing or Dissolution. |

|---|---|---|

| First Parliament | 27 May, 1854 | 9 August, 1854. |

| 31 August, 1854 | 16 September, 1854. | |

| 8 August, 1855 | 15 September, 1855. | |

| Second Parliament | 15 April, 1856 | 16 August, 1856. |

| (There was no session held in the year 1857.) | ||

| 10 April, 1858 | 21 August, 1858. | |

| (There was no session held in the year 1859.) | ||

| 30 July, 1860 | 5 November, 1860. | |

| Third Parliament | 3 June, 1861 | 7 September, 1861. |

| 7 July, 1862 | 15 September, 1862. | |

| 19 October, 1863 | 14 December, 1863. | |

| 24 November, 1864 | 13 December, 1864. | |

| 26 July, 1865 | 30 October, 1865. | |

| Fourth Parliament | 30 June, 1866 | 8 October, 1866. |

| 9 July, 1867 | 10 October, 1867. | |

| 9 July, 1868 | 20 October, 1868. | |

| 1 June, 1869 | 3 September, 1869. | |

| 14 June, 1870 | 13 September, 1870. | |

| Fifth Parliament | 14 August, 1871 | 16 November, 1871. |

| 16 July, 1872 | 25 October, 1872. | |

| 15 July, 1873 | 3 October, 1873. | |

| 3 July, 1874 | 31 August, 1874. | |

| 20 July, 1875 | 21 October, 1875. | |

| Sixth Parliament | 15 June, 1876 | 31 October, 1876. |

| 19 July, 1877 | 10 December, 1877. | |

| 26 July, 1878 | 2 November, 1878. | |

| 11 July, 1879 | 15 August, 1879. | |

| Seventh Parliament | 24 September, 1879 | 19 December, 1879. |

| 28 May, 1880 | 1 September, 1880. | |

| 9 June, 1881 | 24 September, 1881. | |

| Eighth Parliament | 18 May, 1882 | 15 September, 1882. |

| 14 June, 1883 | 8 September, 1883. | |

| 5 June, 1884 | 24 June, 1884. | |

| Ninth Parliament | 7 August, 1884 | 10 November, 1884. |

| 11 June, 1885 | 22 September, 1885. | |

| 13 May, 1886 | 18 August, 1886. | |

| 26 April, 1887 | 15 July, 1887. | |

| Tenth Parliament | 6 October, 1887 | 23 December, 1887. |

| 10 May, 1888 | 31 August, 1888. | |

| 20 June, 1889 | 19 September, 1889. | |

| 19 June, 1890 | 3 October, 1890. | |

| Eleventh Parliament | 23 January, 1891 | 31 January, 1891. |

| 11 June, 1891 | 5 September, 1891. | |

| 23 June, 1892 | 12 October, 1892. | |

| 22 June. 1893 | 8 November, 1893. | |

| Twelfth Parliament | 21 June, 1894. | |

SINCETHE ESTABLISHMENTOF RESPONSIBLE GOVERNMENTIN NEW ZEALANDIN 1856.

| Name of Ministry. | Assumed Office. | Retired. | |

|---|---|---|---|

* Owing to the death of the Premier, the Hon. J. Ballance, on 27th April, 1893. | |||

| 1. | Bell-Sewell | 7 May, 1856 | 20 May, 1856. |

| 2. | Fox | 20 May, 1856 | 2 June, 1856. |

| 3. | Stafford | 2 June, 1856 | 12 July, 1861. |

| 4. | Fox | 12 July, 1861 | 6 August, 1862. |

| 5. | Domett | 6 August, 1862 | 30 October, 1863. |

| 6. | Whitaker-Fox | 30 October, 1863 | 24 November, 1864. |

| 7. | Weld | 24 November, 1864 | 16 October, 1865. |

| 8. | Stafford | 16 October, 1865 | 28 June, 1869. |

| 9. | Fox | 28 June, 1869 | 10 September, 1872. |

| 10. | Stafford | 10 September, 1872 | 11 October, 1872. |

| 11. | Waterhouse | 11 October, 1872 | 3 March, 1873. |

| 12. | Fox | 3 March, 1873 | 8 April, 1873. |

| 13. | Vogel | 8 April, 1873 | 6 July, 1875. |

| 14. | Pollen | 6 July, 1875 | 15 February, 1876. |

| 15. | Vogel | 15 February, 1876 | 1 September, 1876. |

| 16. | Atkinson | 1 September, 1876 | 13 September, 1876. |

| 17. | Atkinson (reconstituted) | 13 September, 1876 | 13 October, 1877. |

| 18. | Grey | 15 October, 1877 | 8 October, 1879. |

| 19. | Hall | 8 October, 1879 | 21 April, 1882. |

| 20. | Whitaker | 21 April, 1882 | 25 September, 1883. |

| 21. | Atkinson | 25 September, 1883 | 16 August, 1884. |

| 22. | Stout-Vogel | 16 August, 1884 | 28 August, 1884. |

| 23. | Atkinson | 28 August, 1884 | 3 September, 1884. |

| 24. | Stout-Vogel | 3 September, 1884 | 8 October, 1887. |

| 25. | Atkinson | 8 October, 1887 | 24 January, 1891. |

| 26. | Ballance | 24 January, 1891 | 1 May, 1893.* |

| 27. | Seddon | 1 May, 1893. | |

| Name of Premier. | Name of Premier. |

|---|---|

|

|

WITH DATESOFTHEIR APPOINTMENTAND DATESOF RETIREMENTOR DEATH.

| Name of Speaker. | Date of Appointment. | Date of Retirement or Death. |

|---|---|---|

| Hon. William Swainson | 16 May, 1854 | 8 August, 1855. |

| Hon. Frederick Whitaker | 8 August, 1855 | 12 May, 1856. |

| Hon. Thomas Houghton Bartley | 12 May, 1856 | 1 July, 1868. |

| Hon. Sir John Larkins Cheese Richardson, Kt. | 1 July, 1868 | 14 June, 1879. |

| Hon. Sir William Fitzherbert, K.C.M.G. | 14 June, 1879 | 23 January, 1891. |

| Hon. Sir Harry Albert Atkinson, K.C.M.G. | 23 January, 1891 | 28 June, 1892. |

| Hon. Henry John Miller | 8 July, 1892. |

WITH DATESOFTHEIR ELECTIONAND DATESOF RETIREMENT.

| Name of Speaker. | Date of Election. | Date of Retirement. |

|---|---|---|

| Sir Charles Clifford, Bart. | 26 May, 1854 | |

| 15 April, 1856 | 3 June, 1861. | |

| Sir David Monro, Kt. Bach. | 3 June, 1861 | |

| 30 June, 1866 | 13 Sept., 1870. | |

| Sir Francis Dillon Bell, K.C.M.G., C.B. | 14 August, 1871 | 21 October, 1875. |

| Sir William Fitzherbert, K.C.M.G. | 15 June, 1876 | 13 June, 1879. |

| Sir George Maurice O'Rorke, Kt. Bach. | 11 July, 1879 | |

| 24 September, 1879 | ||

| 18 May, 1882 | ||

| 7 August, 1884 | ||

| 6 October, 1887 | 3 October, 1890. | |

| Major William Jukes Steward | 23 January, 1891 | 8 November, 1893. |

| Hon. Sir George Maurice O'Rorke, Kt. Bach. | 21 June, 1894. |

CONSULSOF FOREIGN COUNTRIESRESIDINGIN, ORWITH JURISDICTIONOVER, NEW ZEALANDINTHE YEAR 1894.

Netherlands.—Dr. Laon Adrian de Vicq, Melbourne, Consul-General; Charles John Johnston, Wellington, Consul; Edward Bowes Cargill, Dunedin, and David Boosie Cruickshank, Auckland, Vice-Consuls.

Belgium.—Gustave Beckx, Melbourne, Consul-General; Charles John Johnston, Wellington, Alexander Beck, Christchurch, and Arthur Masy, Auckland, Consuls.

Italy.—Cavaliere Nicola Squitti, Barone de Palermiti e Guarna, Melbourne, Consul; Alexander Cracroft Wilson, Christchurch, George Fisher, Wellington, Edward Bowes Cargill, Dunedin, Dr. Francesco Rosetti, Hokitika, Geraldo Guiseppe Perotti, Greymouth, and Patrick Comiskey, Auckland, Consular Agents.

German Empire.—A. Pelldram, Sydney, Consul-General; Bendix Hallenstein, Dunedin, Friedrich Augustus Krull, Wanganui, H. Brown (on leave), Eugene Langguth (acting), Auckland, and Hem-rich von Haast, Christchurch, Consuls; Augustus Friedrich Castendyk, Wellington, Vice-Consul.

France.—William Thomas Locke Travers, Wellington, Vice-Consul; David Boosie Cruickshank, Auckland, Percival Clay Neill, Dunedin, and Hon. Edmund William Parker, Christchurch, Consular Agents.

Sweden and Norway.—Edward Pearce, Wellington, Consul; Edward Valdemar Johansen, Auckland, and Frank Graham, Christchurch, Vice-Consuls.

Denmark.—Edward Valdemar Johansen, Auckland, Consul for the North Island; Emil Christian Skog, Christchurch, Consul for the South Island; Francis Henry Dillon Bell, Wellington, and Edmund Quick, Dunedin, Vice-Consuls.

Spain.—Don Francisco Arenas Y. Bonet, Christchurch, Vice-Consul.

Portugal.—John Duncan, Wellington, Consul; Henry Rees George, Auckland, and Edmund Quick, Dunedin, Vice-Consuls.

Austro-Hungary.—Julius Mergell, Sydney, Consul.

United States.—George H. Wallace, Melbourne, Consul-General; John Darcey Conolly, Auckland, Consul (for New Zealand); Leonard A. Bachelder, Auckland, Vice-Consul; Albert Cuff, Christchurch, Henry Stephenson, Russell, Robert Wyles, Mongonui, Thomas Cahill, M.D., Wellington, and Reynolds Driver, Dunedin, Consular Agents.

Nicaragua.—J. H. Amora, Sydney, Consul-General for Australasia.

Chili.—William Henry Eldred, Sydney, Consul-General; Edmund Quick, Dunedin, Consular Agent.

Hawaiian Islands.—James Cruickshank, Auckland, Reynolds Driver (acting), Dunedin, Consuls.

(With their Addresses).

NEW ZEALAND.

Sir W. B. Perceval, K.C.M.G., Westminster Chambers, 13, Victoria Street, S.W. Secretary—Walter Kennaway, C.M.G.

AUSTRALIA.

New South Wales.—The Hon. Sir Saul Samuel, K.C.M.G., C.B., Westminster Chambers, 9, Victoria Street, S.W. Secretary—S. Yardley, C.M.G.

Victoria.—The Hon. Duncan Gillies, 15, Victoria Street, S.W. Secretary—

South Australia.—The Hon. T. Playford, Victoria Chambers, 15, Victoria Street, S.W. Secretary—Samuel Deering.

Queensland.—The Hon. Sir James F. Garrick, K.C.M.G., Westminster Chambers, 1, Victoria Street, S.W. Secretary—Charles Shortt Dicken, C.M.G.

Western Australia.—The Hon. Sir Malcolm Fraser, K.C.M.G., 15, Victoria Street, Westminster, S.W. Secretary—Reginald Hare.

Tasmania.—The Hon. Sir Robert G. W. Herbert, G.C.B., Westminster Chambers, 5, Victoria Street, S.W. Secretary—

(DOWNING STREET, S.W., LONDON), WITH DATESOF APPOINTMENT.

Principal Secretary of State for the Colonies—The Most Hon. the Marquis of Ripon, K.G., 17th August, 1892.

Under-Secretaries: Permanent—The Hon. Sir Robert Henry Meade, K.C.B., 1st February, 1892; Parliamentary—Sydney Charles Buxton, M.P., 17th August, 1892.

Assistant Under-Secretaries—John Bramston, D.C.L., C.B., 30th June, 1876; Edward Wingfield, B.C.L., C.B., 19th July, 1878; Edward Fairfield, C.M.G., 1st February, 1892.

Private Secretary to Secretary of State — F. S. St. Quintin. Assistant Private Secretary—Hartmann W. Just, B.A.

DOWNING STREET, S.W. CITY OFFICE: 1, TOKENHOUSE BUILDINGS, E.C., LONDON.

Crown Agents—Sir Montagu Frederick Ommaney, K.C.M.G., and Ernest Edward Blake.

Bell, Hon. Sir Francis Dillon, Knt. Bach., 1873; K.C.M.G., 1881; C.B., 1886.

Buckley, Hon. Sir Patrick Alphonsus, K.C.M.G., 1892.

Buller, Sir Walter Lawry, F.R.S., C.M.G., 1875; K.C.M.G., 1886.

FitzGerald, James Edward, Esq., C.M.G., 1870.

Grace, Hon. Morgan Stanislaus, C.M.G., 1890.

Grey, Bight Hon. Sir George, K.C.B., 1848; P.C., 1894.

Hall, Hon. Sir John, K.C.M.G., 1882.

Hector, Sir James, F.R.S., C.M.G., 1875; K.C.M.G., 1887.

Larnach, Hon. William James Mudie, C.M.G., 1879.

O'Rorke, Hon. Sir George Maurice, Knt. Bach., 1880.

Perceval, Sir Westby Brook, K.C.M.G, 1894.

Prendergast, Sir James, Knt. Bach., 1881.

Richardson, Hon. Edward, C.M.G., 1879.

Roberts, John, Esq., C.M.G., 1891.

Stafford, Hon. Sir Edward William, K.C.M.G., 1879; G.C.M.G., 1887.

Stout, Hon. Sir Robert, K.C.M.G., 1886.

Vogel, Hon. Sir Julius, C.M.G., 1872; K.C.M.G., 1875.

Whitmore, Hon. Colonel Sir George Stoddart, C.M.G., 1869; K.C.M.G., 1882.

PERSONSALLOWEDTORETAINTHE TITLEOF “HONOURABLE” WITHIN HER MAJESTY'S DOMINIONS.

By despatch from the Secretary of State for the Colonies, dated Downing Street, 15th June, 1893, His Excellency the Governor was apprised that the title of “Honourable,” appertaining to Members of the Executive and Legislative Councils in colonies possessing Responsible Government, whether confined to duration of office or continued for life, is approved by Her Majesty for use and recognition throughout her dominions, either during office or for life, as the case may be.

By further despatch of 10th March, 1894, the Secretary of State announces that he is prepared in future to submit for the approval of the Queen the recommendation of the Governor of any colony having Responsible Government that the President of the Legislative Council or the Speaker of the Legislative Assembly may, on quitting office after three years’ service in their respective offices, be permitted to retain the title of “Honourable.” This title has since been conferred on Sir F. D. Bell, Sir G. M. O'Rorke, and Major William Jukes Steward.

Besides the Members of the Executive and Legislative Councils, the following ex-Ministers whose names do not appear in the list given above are allowed, as such, to retain the title of “Honourable”: Bryce, John, 1884; Dick, Thomas, 1884; Fergus, Thomas, 1891; Gisborne, William, 1873; Haultain, Colonel T. M., 1870; Hislop, Thomas W., 1891; Johnston, Walter W., 1884; Mitchelson, Edwin, 1891; Oliver, Richard, 1884; Reynolds, William H., 1876; Richardson, George F., 1891; Rolleston, William, 1884; Tole, Joseph A., 1888.

GLASGOW, His Excellency the Right Honourable David, Earl of, G.C.M.G., a Captain of the Royal Navy, served in the White Sea during the Russian war, and in the Chinese war of 1857, and retired in 1878; born, 1833; married, in 1873, Dorothea Thomasina, daughter of Sir Edward Hunter-Blair; appointed February 24, and assumed office June 7, 1892, as Governor and Commander-in-Chief in and over Her Majesty's Colony of New Zealand and its Dependencies. Salary, £5,000. Residences: Government House, Wellington; and Government House, Auckland.

Private Secretary and Aide-de-Camp—Edward Hay Mackenzie Elliot (Major, South Lancashire Regiment).

Aide-de-Camp — Edward Francis Clayton (Lieutenant, Scots-Guards). Extra Aide-de-Camp—Stair Hathorn Johnston Stewart (Captain, late 20th Hussars).

ADMINISTRATOROFTHE GOVERNMENT.—A dormant commission empowers the Chief Justice of the Colony for the time being to administer the Government in case of the death, incapacity, removal, or departure of the Governor.

His Excellency the GOVERNOR presides.

Hon. R. J. Seddon, Premier, Minister for Public Works, Minister of Defence, and Native Minister.

Hon. Sir P. A. Buckley, K.C.M.G., Attorney-General and Colonial Secretary.

Hon. W. P. Reeves, Minister of Education, Commissioner of Stamp Duties, and Minister of Labour.

Hon. A. J. Cadman, Minister of Justice and Minister of Mines.

Hon. J. McKenzie, Minister of Lands and Immigration, Minister of Agriculture, and Commissioner of Forests.

Hon. J. G. Ward, Colonial Treasurer, Postmaster-General, Electric Telegraph Commissioner, Commissioner of Customs, Minister of Marine, and Minister of Industries and Commerce.

Hon. J. Carroll (without portfolio), representing the Native race.

Hon. W. Montgomery (without portfolio).

Clerk of Executive Council—Alexander James Willis.

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL.

The number of members at present constituting the Legislative Council is forty-six. The number cannot be less than ten, but is otherwise unlimited. Prior to 1891 Councillors summoned by the Governor held their appointments for life, but on the 17th of September of that year an Act was passed making future appointments to the Council tenable for seven years only, to be reckoned from the date of the writ of summons of the Councillor's appointment, though every such Councillor may be reappointed. The qualifications are that the person to be appointed be of the full age of twenty-one years, and a subject of Her Majesty, either natural - born or naturalised by or under any Act of the Imperial Parliament or by or under any Act of the General Assembly of New Zealand. All contractors to the public service to an amount of over £50 and Civil servants of the colony are ineligible to become Councillors. Payment of Councillors is at the rate of £150 a year, payable monthly Actual travelling-expenses to and from Wellington are also allowed. A deduction of £1 5s. per sitting day is made in case of an absence, except through illness or other unavoidable cause, exceeding five sitting days in any one session. A seat is vacated by any member of the Council — (1), If he takes any oath or makes any declaration or acknowledgment of allegiance, obedience, or adherence to any foreign Prince or Power; or (2), if he does, or concurs in, or adopts any act whereby he may become a subject or citizen of any foreign State or Power, or is entitled to the rights, privileges, or immunities of a subject of any foreign State or Power; or (3), if he is a bankrupt, or compounds with his creditors under any Act for the time being in force; or (4), if he is a public defaulter, or is attainted of treason, or is convicted of felony or any infamous crime; or (5), if he resigns his seat by writing under his hand addressed to and accepted by the Governor; or (6), if for more than one whole session of the General Assembly he fails, without permission of the Governor notified to the Council, to give his attendance in the Council. The presence of one-fourth of the members of the Council, exclusive of those who have leave of absence, is necessary to constitute a meeting for the exercise of its powers. This rule, however, may be altered from time to time by the Council. The ordinary sitting-days are Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Thursdays, and Fridays, from 2.30 p.m. to 5 p.m., resuming again at 7.30 when necessary.

ROLLOF MEMBERSOFTHE HONOURABLETHE LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL,

Stating the Provincial District and the Date of Writ of Summons.

Speaker—The Hon. HENRY JOHN MILLER.

Chairman of Committees—The Hon. WILLIAM DOUGLAS HALL BAILLIE.

| Name. | Provincial District. | Date of Appointment |

|---|---|---|

| Acland, the Hon. John Barton Arundel | Canterbury | 8 July, 1865. |

| Baillie, the Hon. William Douglas Hall | Marlborough | 8 March, 1861. |

| Barnicoat, the Hon. John Wallis | Nelson | 14 May, 1883. |

| Bolt, the Hon. William Mouat | Otago | 15 October, 1892. |

| Bonar, the Hon. James Alexander | Westland | 27 June, 1868. |

| Bowen, the Hon. Charles Christopher | Canterbury | 23 January, 1891. |

| Buckley, the Hon. Sir Patrick Alphonsus, K.C.M.G. | Wellington | 25 July, 1878. |

| Dignan, the Hon. Patrick | Auckland | 3 February, 1879. |

| Feldwick, the Hon. Henry | Otago | 15 October, 1892. |

| Grace, the Hon. Morgan Stanislaus, C.M.G. | Wellington | 13 May, 1870. |

| Hart, the Hon. Robert; | Wellington | 9 July, 1872. |

| Holmes, the Hon. Mathew | Otago | 19 June, 1866. |

| Jenkinson, the Hon. John Edward | Canterbury | 6 June, 1893. |

| Jennings, the Hon. William Thomas | Auckland | 15 October, 1892. |

| Johnston, the Hon. Charles John | Wellington | 23 January, 1891. |

| Kelly, the Hon. Thomas | Taranaki | 15 October, 1892. |

| Kenny, the Hon. Courtney William Aylmer Thomas | Marlborough | 15 May, 1885. |

| Kerr, the Hon. James | Westland | 15 October, 1892. |

| McCullough, the Hon. William | Auckland | 15 October, 1892. |

| MacGregor, the Hon. John | Otago | 15 October, 1892. |

| McLean, the Hon. George | Otago | 19 December, 1881. |

| Mantell, the Hon. Walter Baldock Durant | Wellington | 19 June, 1866. |

| Miller, the Hon. Henry John (Speaker) | Otago | 8 July, 1865. |

| Montgomery, the Hon. William | Canterbury | 15 October, 1892. |

| Morris, the Hon. George Bentham | Auckland | 15 May, 1885. |

| Oliver, the Hon. Richard | Otago | 10 November, 1881. |

| Ormond, the Hon. John Davies | Hawke's Bay | 23 January, 1891. |

| Peacock, the Hon. John Thomas | Canterbury | 3 June, 1873. |

| Pharazyn, the Hon. Robert | Wellington | 15 May, 1885. |

| Pollen, the Hon. Daniel | Auckland | 12 May, 1873. |

| Reynolds, the Hon. William Hunter | Otago | 6 May, 1878. |

| Richardson, the Hon. Edward, C.M.G. | Wellington | 15 October, 1892. |

| Rigg, the Hon. John | Wellington | 6 June, 1893. |

| Scotland, the Hon. Henry | Taranaki | 24 February, 1868. |

| Shephard, the Hon. Joseph | Nelson | 15 May, 1885. |

| Shrimski, the Hon. Samuel Edward | Otago | 15 May, 1885. |

| Stevens, the Hon. Edward Cephas John | Canterbury | 7 March, 1882. |

| Stewart, the Hon. William Downie | Otago | 23 January, 1891. |

| Swanson, the Hon. William | Auckland | 15 May, 1885. |

| Taiaroa, the Hon. Hori Kerei | Otago | 15 May, 1885. |

| Wahawaha, the Hon. Major Ropata, N.Z.C. | Auckland | 10 May, 1887. |

| Walker, the Hon. Lancelot | Canterbury | 15 May, 1885. |

| Walker, the Hon. William Campbell | Canterbury | 15 October, 1892. |

| Whitmore, the Hon. Sir George Stoddart, K.C.M.G. | Hawke's Bay | 31 August, 1863. |

| Whyte, the Hon. John Blair | Auckland | 23 January, 1891. |

| Williams, the Hon. Henry | Auckland | 7 March, 1882. |

Clerk of Parliaments, Clerk of the Legislative Council, and Examiner of Standing Orders upon Private Bills—Leonard Stowe.

Clerk-Assistant—Arthur Thomas Bothamley.

Second Clerk-Assistant—George Moore.

Interpreter—Henry S. Hadfield.

The number of members constituting the House of Representatives is seventy-four—seventy Europeans and four Maoris. This number was fixed by the Act of 1887, which came for the first time into practical operation at the general election of 1890. Previously (from 1881) the House consisted of ninety-five members—ninety-one Europeans and four Maoris. The North Island returns thirty European members, and the Middle Island forty. The Cities of Auckland, Wellington, Christchurch, and Dunedin return each three members, and all other electoral districts one each. The elections are triennial, except in the case of a dissolution by the Governor. The qualification for membership is simply registration as an elector, and not coming within the meaning of section 8 of “The Electoral Act, 1893.” All contractors to the public service of New Zealand to whom any public money above the sum of £50 is payable, directly or indirectly, in any one financial year, and the Civil servants of the colony, are incapable of being elected as or of sitting or voting as members. The payment made to members of the House of Representatives is £20 per month, amounting to £240 per annum. £2 for every sitting-day exceeding five is deducted on account of absence during session not due to sickness or other unavoidable cause. Travelling-expenses to and from Wellington are also allowed. This scale of payment came into force on the 1st January, 1893, under the provisions of “The Payment of Members Act, 1892.” Twenty members, exclusive of the Speaker, constitute a quorum. Unless otherwise ordered, the sitting-days of the House are Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Thursdays, and Fridays, from 2.30 to 5.30, resuming at 7.30 p.m. Order of admission to the Speaker's Gallery is by ticket obtained from the Speaker. The Strangers’ Gallery is open free to the public.

ROLLOF MEMBERSOFTHE HOUSEOF REPRESENTATIVES,

With the Name of the District for which they are elected, and the Date of Notification of Return of Writ.